PATENT DUCTUS ARTERIOSUS

PATENT DUCTUS ARTERIOSUS

PDA is a heart problem that is frequently noted in the first few weeks or months after birth. It is characterized by the persistence of a normal fetal connection between the aorta and the pulmonary artery which allows oxygen-rich (red) blood that should go to the body to recirculate through the lungs.

All babies are born with this connection between the aorta and the pulmonary artery. While your baby was developing in the uterus, it was not necessary for blood to circulate through the lungs because oxygen was provided through the placenta. During pregnancy, a connection was necessary to allow oxygen-rich (red) blood to bypass your baby’s lungs and proceed into the body. This normal connection that all babies have is called a ductus arteriosus.

At birth, the placenta is removed when the umbilical cord is cut. Your baby’s lungs must now provide oxygen to his or her body. As your baby takes the first breath, the blood vessels in the lungs open up, and blood begins to flow through them to pick up oxygen. At this point, the ductus arteriosus is not needed to bypass the lungs. Under normal circumstances, within the first few days after birth, the ductus arteriosus closes and blood no longer passes through it.

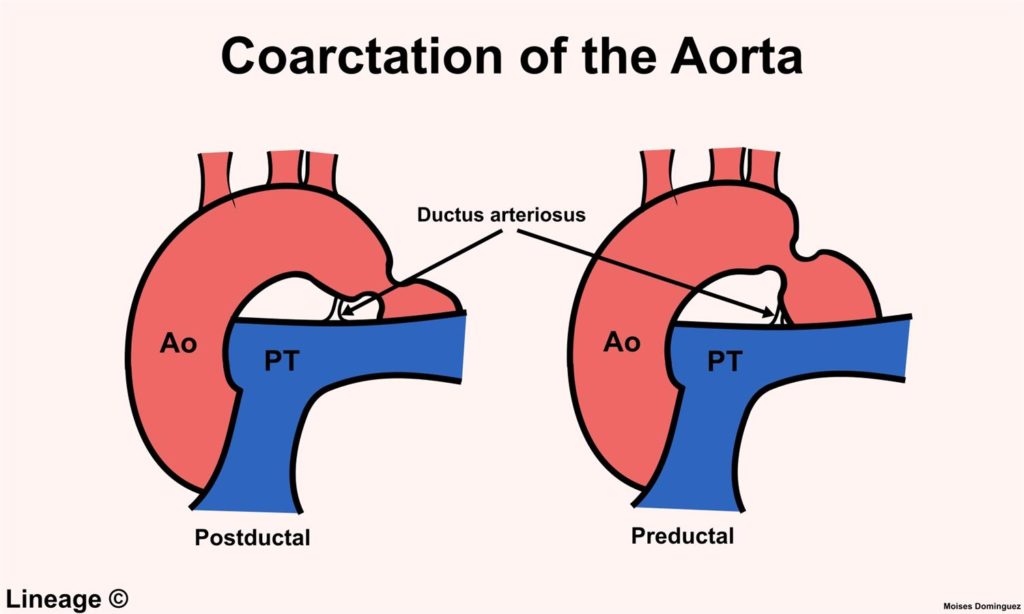

Illustration of the anatomy of a heart with a patent ductus arteriosus

In some babies, however, the ductus arteriosus remains open (patent) and the condition now becomes known as patent ductus arteriosus (PDA). The opening between the aorta and the pulmonary artery allows oxygen-rich (red) blood to recirculate into the lungs.

Patent ductus arteriosus occurs twice as often in girls as in boys.

CAUSES OF PDA

A PDA is almost always present at birth. In some children, the PDA does not close. Although exact reasons why this happens in some patients and not in others are not known, the most common association for a PDA is prematurity.

PDA can also occur in combination with other heart defects.

WHY IS PDA A CONCERN

When the ductus arteriosus stays open, oxygen-rich (red) blood passes from the aorta to the pulmonary artery, mixing with the oxygen-poor (blue) blood already flowing to the lungs. The blood vessels in the lungs have to handle a larger amount of blood than normal. How well the lung vessels are able to adapt to the extra blood flow depends on how big the PDA is and how much blood is able to pass through it from the aorta.

Extra blood causes higher pressure in the blood vessels in the lungs. The larger the volume of blood that goes to the lungs at high pressure, the more the lungs have to cope with this extra blood at high pressure.

Children may have difficulty breathing because of this extra blood flow to the lungs at high pressure. They may remain on the ventilator for a longer period of time if they are premature. The support from the ventilator also may be high, due to this extra blood flow to the lungs.

Rarely, untreated PDA may lead to long-term lung damage. This is uncommon, however, since most children will have been treated for their PDA before the lungs get damaged.

Often, the PDA may be “silent,” that is, causing no symptoms. This is especially true in older patients (beyond the first few months of life) with small PDAs.

SYMPTOMS

The size of the connection between the aorta and the pulmonary artery will affect the type of symptoms noted, the severity of symptoms, and the age at which they first occur. The larger the opening, the greater the amount of blood that passes through that overloads the lungs.

A child with a small patent ductus arteriosus might not have any symptoms, and your child’s doctor may have only noted the defect by hearing a heart murmur. Other infants with a larger PDA may exhibit different symptoms. The following are the most common symptoms of PDA. However, each child may experience symptoms differently. Symptoms may include

Fatigue

Sweating

Rapid breathing

Heavy breathing

Congested breathing

Disinterest in feeding, or tiring while feeding

Poor weight gain

The symptoms of a PDA may resemble other medical conditions or heart problems. Always consult your child’s doctor for a diagnosis.

DIAGNOSIS

Your child’s doctor may have heard a heart murmur during a physical examination, and referred your child to a pediatric cardiologist for a diagnosis. In this case, a heart murmur is a noise caused by the turbulence of blood flowing through the PDA.

A pediatric cardiologist specializes in the diagnosis and medical management of congenital heart defects, as well as heart problems that may develop later in childhood. The cardiologist will perform a physical examination, listening to the heart and lungs, and make other observations that help in the diagnosis. The location within the chest where the murmur is heard best, as well as the loudness and quality of the murmur (such as, harsh or blowing) will give the cardiologist an initial idea of which heart problem your child may have. Diagnostic testing for congenital heart disease varies by the child’s age, clinical condition, and institutional preferences. Some tests that may be recommended include the following

:Chest X-ray.

A diagnostic test that uses invisible X-ray beams to produce images of internal tissues, bones, and organs onto film. With a PDA, the heart may be enlarged due to larger amounts of blood flow recirculating through the lungs back to the heart. Also, there may be changes that take place in the lungs due to extra blood flow that can be seen on an X-ray.

Electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG). A test that records the electrical activity of the heart, shows abnormal rhythms (arrhythmias or dysrhythmias), and detects heart muscle stress.

Echocardiogram (echo). A procedure that evaluates the structure and function of the heart by using sound waves recorded on an electronic sensor that produce a moving picture of the heart and heart valves. An echo can show the pattern of blood flow through the PDA, and determine how large the opening is, as well as how much blood is passing through it. An echo is the most common way that a PDA is diagnosed.

Cardiac catheterization. A cardiac catheterization is an invasive procedure that gives very detailed information about the structures inside the heart. Under sedation, a small, thin, flexible tube (catheter) is inserted into a blood vessel in the groin, and guided to the inside of the heart. Blood pressure and oxygen measurements are taken in the four chambers of the heart, as well as the pulmonary artery and aorta. Contrast dye is also injected to more clearly visualize the structures inside the heart. The cardiac catheterization procedure may also be an option for treatment. During the procedure, the child is sedated and a small, thin, flexible tube (catheter) is inserted into a blood vessel in the groin and guided to the inside of the heart. Once the catheter is in the heart, the cardiologist will pass a special device, either a coil or a PDA occluder (depending on the size of the PDA). This device will close the PDA and therefore stop the blood flow through the PDA.

TREATMENT OF PDA

A small patent ductus arteriosus may close spontaneously as your child grows. A PDA that causes symptoms will require medical management, and possibly even surgical repair. Your child’s cardiologist will check periodically to see whether the PDA is closing on its own. If a PDA does not close on its own, it will be repaired to prevent lung problems that will develop from long-time exposure to extra blood flow. Treatment may include:

Medical management. In premature infants, an intravenous (IV) medication called indomethacin may help close a patent ductus arteriosus. Indomethacin is related to aspirin and ibuprofen and works by stimulating the muscles inside the PDA to constrict, thereby closing the connection. Your child’s doctor can answer any further questions you may have about this treatment. As previously mentioned, some children will have no symptoms, and require no medications. However, others may need to take medications to help the heart and lungs work better. Medications may be prescribed, such as diuretics. Diuretics help the kidneys remove excess fluid from the body. This may be necessary because the body’s water balance can be affected when the heart is not working as efficiently as it could. Your doctor may also ask you to restrict the amount of fluid your child takes in.

Adequate nutrition. Most infants with PDA eat and grow normally, but premature infants or those infants with a large PDA may become tired when feeding, and are not able to eat enough to gain weight. Options that can be used to ensure your baby will have adequate nutrition include the following:

High-calorie formula or breast milk. Special nutritional supplements may be added to formula or pumped breast milk that increase the number of calories in each ounce, thereby allowing your baby to drink less and still consume enough calories to grow properly.

Supplemental tube feedings. Feedings given through a small, flexible tube that passes through the nose, down the esophagus, and into the stomach, can either supplement or take the place of bottle-feedings. Infants who can drink part of their bottle, but not all, may be fed the remainder through the feeding tube. Infants who are too tired to bottle-feed may receive their formula or breast milk through the feeding tube alone.

PDA repair or closure. The majority of children and some infants with PDA are candidates for repair in the cardiac cath lab. The goal is to repair the PDA before the lungs become diseased from too much blood flow and pressure and to restore an efficient pattern of blood flow. Surgical repair is also indicated if one of the previously mentioned conservative treatments have not been successful. Repair is usually indicated in infants younger than 6 months of age who have large defects that are causing symptoms, such as poor weight gain and rapid breathing. For infants who do not exhibit symptoms, the repair may often be delayed until after 6 to 12 months of age. Your child’s cardiologist will recommend when the repair should be performed. Transcatheter coil closure of the PDA is frequently performed first if possible because it is minimally invasive. Children need to be at least 5 kg to be considered for transcatheter closure. Thus, premature infants, because of their small size, are not candidates for this procedure, and require surgical closure of the PDA. Your child’s PDA may be repaired surgically in the operating room. The surgical repair, also called PDA ligation, is performed under general anesthesia. The procedure involves closing the open PDA with stitches or clips in order to prevent the surplus blood from entering your child’s lungs.

POSTPROCEDURE CARE FOR YOUR CHILD :

Cath lab repair or closure procedure. When the procedure is complete, the catheter(s) will be withdrawn. Several gauze pads and a large piece of medical tape will be placed on the site where the catheter was inserted to prevent bleeding. In some cases, a small, flat weight or sandbag may be used to help keep pressure on the catheterization site and decrease the chance of bleeding. If blood vessels in the leg were used, your child will be told to keep the leg straight for a few hours after the procedure to minimize the chance of bleeding at the catheterization site. Your child will be taken to a unit in the hospital where he or she will be monitored by nursing staff for several hours after the test. The length of time it takes for your child to wake up after the procedure will depend on the type of medicine given to your child for relaxation prior to the test, and also on your child’s reaction to the medication. After the procedure, your child’s nurse will monitor the pulses and skin temperature in the leg or arm that was used for the procedure. Your child may be able to go home after a specified period of time, providing he or she does not need further treatment or monitoring. You will receive written instructions regarding care of the catheterization site, bathing, activity restrictions, and any new medications your child may need to take at home.

Surgical repair. Some children who undergo PDA ligation may need to spend some time in the intensive care unit after surgery. Others may return to a regular hospital room. Your child will be kept as comfortable as possible with medications that relieve pain or anxiety. The staff will also be asking for your input as to how best to soothe and comfort your child. You will also learn how to care for your child at home before your child is discharged. The staff will give you instructions regarding medications, activity limitations, and follow-up appointments before your child is discharged. Most children will only need to stay in the hospital for a few days after the operation.

HOME CARE

Most infants and older children feel comfortable when they go home. Pain medications, such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen, may be recommended to keep your child comfortable. Your child’s doctor will discuss pain control before your child is discharged from the hospital.

Often, infants who fed poorly prior to surgery have more energy after the recuperation period, and begin to eat better and gain weight faster.

After surgery, older children usually have a fair tolerance for activity. Within a few weeks, your child should be fully recovered and able to participate in normal activity.

You will receive additional instructions from your child’s doctors and the hospital staff.

other related posts: