Expressive Aphasia

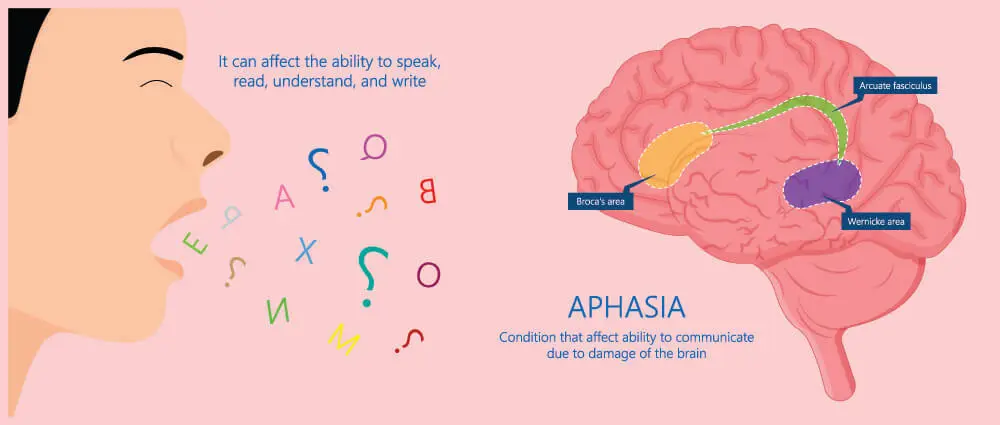

Introduction

A kind of aphasia called expressive aphasia, commonly referred to as Broca’s aphasia, is characterized by a partial loss of the capacity to create language (spoken, physical, or written), however understanding typically remains unaffected. An individual with expressive aphasia will speak with effort.

Speech often includes key content terms but omits function words, such as prepositions and articles, which have more grammatical than literal meaning. The term “telegraphic speech” applies to this. Even if the statement is technically incorrect, the intended meaning may still be comprehended. A person with very severe expressive aphasia may only be able to talk in single-word sentences. Due to the difficulties in comprehending complicated language, comprehension is often mildly to moderately impaired in expressive aphasia.

It is brought on by inherited damage to the frontal lobes of the brain, including Broca’s area. It is a part of a wider group of illnesses referred to as aphasia. In contrast to receptive aphasia, people with expressive aphasia can talk in grammatical sentences devoid of semantic meaning and typically also struggle with understanding.

Different from dysarthria, which is characterized by a patient’s inability to appropriately move the tongue and mouth muscles to create speech, is expressive aphasia. Apraxia of speech, a motor condition marked by an inability to develop and sequence motor plans for speaking, is distinct from expressive aphasia in another way.

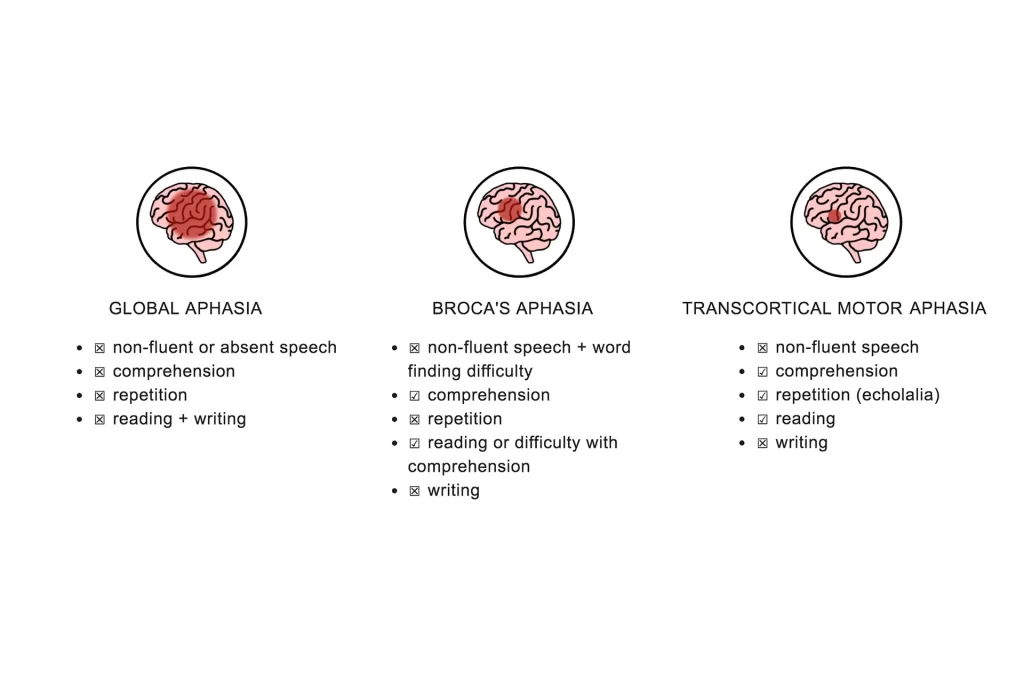

Aphasia: 3 Types

There are three main categories of aphasia:

- Broca’s aphasia.

- Wernicke’s aphasia.

- Global aphasia.

Causes of Expressive Aphasia

- More common

- Stroke or brain anoxia.

- Brain tumor

- Brain trauma

- Less common

- Autoimmune disease

- Paraneoplastic syndrome

- Micrometastasis

- neurodegenerative disorders

- Certain infections (e.g., Bartonella henselae)

- Metabolic disease (e.g., hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state)

Common causes

A stroke is the most frequent reason for expressive aphasia. Hypoperfusion (lack of oxygen) to a portion of the brain, which is frequently brought on by thrombosis or embolism, is what causes a stroke. In between 34 and 38% of stroke patients, aphasia in some way manifests.

About 12% of newly diagnosed situations of aphasia brought on by stroke include expressive aphasia.

Expressive aphasia is typically brought on by a stroke in or close to Broca’s region. The lower premotor cortex of the language-dominant hemisphere has a region called Broca’s area, which is in charge of planning motor speaking motions.

However, individuals with strokes in other parts of the brain have experienced episodes of expressive aphasia. Patients with expressive aphasia’s traditional symptoms typically have more severe brain lesions, but those with bigger, broader lesions typically have a range of symptoms that can either be labelled as global aphasia or left unclassified.

The following conditions can also result in expressive aphasia: extradural abscess, tumour, cerebral haemorrhage, and brain injury.

It’s essential to comprehend how the brain works on the lateral side if you want to know what parts of the brain harm expressive aphasia. It was once thought that people who are left- or right-handed had different areas in their brains where language is produced. If this were the case, a left-handed person should have aphasia if the corresponding part of Broca’s area in the right hemisphere is damaged. Even left-handed people often solely use their left hemisphere for linguistic tasks, according to more recent studies. However, right-hemispheric dominance of language is more common in left-handed people.

Uncommon causes

Primary hypotheses for several cases of expressive aphasia, particularly when presenting with additional psychiatric disturbances and focal neurological deficits, include primary autoimmune phenomena and autoimmune phenomena that are secondary to cancer (as a paraneoplastic syndrome). There are several case reports describing expressive aphasia, which predominates in the more specific accounts of paraneoplastic aphasia. It is conceivable that some instances with paraneoplastic aphasia are actually very tiny metastases to the vocal motor areas, despite the fact that most cases try to rule out micro-metastasis.

Aphasia can be a symptom of neurodegenerative diseases. Either expressive or fluent aphasia may be a symptom of Alzheimer’s disease. There have been case reports of expressive aphasia being a symptom of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.

Signs and symptoms

Non-fluent aphasias like Broca’s (expressive) aphasia cause slow, complicated speaking in the sufferer.

The word consonant and vowel misarticulations or distortions, or phonetic disintegration, are frequent. Only single words or words in groups of two or three can be produced by those with expressive aphasia. There are sometimes long pauses between syllables, and multisyllabic words might be uttered one syllable at a time with pauses in between. Shorter utterances and the existence of self-repairs and disfluencies weaken the prosody of someone with Broca’s aphasia. Stress patterns and intonation are also lacking.

In the example below, a patient with Broca’s aphasia tries to explain how he arrived at the medical facility for dental treatment in the text below:

Yes, Monday… er… Dad and Peter H… (using his own name) and Dad… er… hospital… and Wednesday… er… Wednesday, nine o’clock… and uh… Thursday… er… ten o’clock, ah doctors… two… an’ doctors… and er… teeth… yah.

The majority of the words in an expressive aphasic person’s speech are significant words such nouns, verbs, and some adjectives.

While “and” is often employed in the speech of the majority of aphasia patients, other function words like conjunctions, articles, and prepositions are rarely utilized. The person’s speech is agrammatic because function words are missing from it. A person with aphasia’s communication partner could claim that the individual’s speech sounds telegraphic as a result of awkward sentence structure and jumbled words. An individual with expressive aphasia could, for instance, remark, “Smart… university… smart… good… good…”

Patients with Broca’s aphasia often have well-preserved self-monitoring abilities. They are more likely to experience despair and angry outbursts than individuals with other types of aphasia because they are typically aware of their communication limitations.

Generally speaking, word understanding is maintained, enabling patients to have usable receptive language abilities. Broca’s aphasia patients can still comprehend much of the ordinary speech around them, although they may experience higher-level receptive language difficulties. When conversing with someone who has expressive aphasia, it is preferable to utilize basic language because complicated phrases significantly decrease understanding. The difficulty in comprehending words or sentences with unconventional structures serves as an illustration of this. The typical Broca’s aphasia patient will misunderstand “the man is bitten by the dog” by changing the subject and object to “the dog is bitten by the man.”

People with expressive aphasia typically have higher reading and speaking comprehension than writing and speaking ability. The person’s writing will seem forced, lack cohesiveness, and use primarily content terms, much like their speaking. There will probably be clunky, twisted, and maybe even missing letters. Even if reading and listening are mostly unaffected, aphasia assessments nearly always reveal minor abnormalities in both reading and listening comprehension.

A lesion affecting Broca’s areas may also cause hemiparesis (weakness of both limbs on the identical side of the body) or hemiplegia (paralysis of each limb on the similar side of the body) because they are anterior to the primary motor cortex, which controls the movement of the face, hands, and arms. Because of the way the brain is built, the left hemisphere controls the limbs on the right side of the body and vice versa. Therefore, in people with Broca’s aphasia, hemiplegia or hemiparesis frequently arises on the right side of the body when Broca’s region or neighboring areas in the left hemisphere are damaged.

Patients with expressive aphasia might range in severity. It may be challenging to identify language issues in some persons since they only have minor deficiencies. In the worst circumstances, patients might only be able to utter one syllable. Even in these situations, over-learned and rote-learned speech patterns may still be preserved; for instance, some individuals can count to ten but struggle to do the same in fresh discussion.

Pathophysiology

The Broca area is comprised of Brodmann areas 44 and 45 and is located in the inferior frontal lobe of the dominant side of the brain.

60% of left-handed persons and 96% to 99% of right-handed people have their language function lateralized to the left hemisphere.

The contralateral hemisphere, basal ganglia, frontal lobe, and cerebellum are all connected to the Broca region via a variety of routes.

There is a breakdown between one’s thinking and one’s linguistic skills as a result of a lesion in the Broca region. Patients commonly think they comprehend what they’re supposed to say but are struggling to say it because of this. In other words, they are unable to put their brain pictures and images into words. The typical fluency of speech is impacted by this. The Broca region plays a role in putting sounds into words and words into sentences, which establishes linkages between linguistic components, which may explain the loss of language function.

Treatment of Expressive Aphasia

The main form of intervention for someone with any sort of aphasia is speech and language therapy. Treatment objectives comprise:

- enhancing the utilization of the residual linguistic skills

- regaining lost linguistic skills to the greatest extent feasible

- discovering novel methods of communication

- A person may participate in both individual and group treatment.

While group therapy provides people an opportunity to practice connecting with others, individual treatment is tailored specifically to a person’s requirements. Additionally, video chats can be used to digitally get speech and language treatment.

A speech therapist could attempt several things, like:

- Repetition: Using helpful words or phrases repeatedly to enhance or restore one’s language abilities might be beneficial.

- Depending on the severity of the initial brain damage, people can continue to improve in this region years thereafter.

- Melodic intonation: In this strategy, a speech therapist encourages a patient to sing instead of using words to express themselves. A person may be able to talk more smoothly if they sing what they are attempting to say using this strategy since it entails activating a different portion of the brain to communicate.

- Object boards: These boards display images of items that a person might require or want. You may converse by pointing to the items on the board. A comparable purpose can also be served by electronic gadgets.

Going to organizations and clubs with other stroke survivors may be beneficial for those with aphasia. This might apply to theatrical clubs, art clubs, or literature clubs. Participating in social activities can boost one’s self-esteem and make them feel less alone.

Transcranial stimulation and a number of pharmacological therapies are two innovative treatments that are now the subject of clinical testing. In order to stimulate nerve cells, a magnetic field or electrical current is used.

Constraint-induced therapy

Constraint-induced movement treatment (CIMT), created by Dr. Edward Taub at the University of Alabama in Birmingham, has similar foundational ideas to constraint-induced aphasia therapy (CIAT). Constraint-induced movement therapy is based on the premise that a person with an impairment (physical or communicative) acquires a “learned nonuse” by making up for the lost function in other ways, for as sketching for an aphasic patient or utilizing an intact limb.

In constraint-induced mobility therapy, the patient is made to utilize the injured limb while the alternate limb is restrained with a glove or sling. In constraint-induced aphasia therapy, the interaction is shaped by the need for communication in a language game context, picture cards, barriers that prevent players from seeing each other’s cards, and other materials so that patients are compelled (or “constrained”) to use their remaining verbal skills to win the communication game.

The use of language in a communication environment in which it is strongly related to (nonverbal) activities is one of two key tenets of constraint-induced aphasia therapy. Treatment sessions can run up to 6 hours over the course of 10 days. The neurology of learning at the level of nerve cells (synaptic plasticity) and the linkage of the language and action cortex systems in the human brain are the driving forces behind these ideas. Contrary to traditional treatment, constraint-induced therapy strongly believes that compensatory strategies, such as gesturing or writing, should not be utilized unless absolutely essential, even in daily life.

Increased neuroplasticity is thought to be the mechanism via which CIAT functions. It is thought that by limiting a person to speaking exclusively, the brain is more likely to recruit new neural networks and rebuild damaged ones in order to make up for lost function.

Patients with chronic aphasia (lasting more than six months) have seen the best CIAT outcomes. Studies on CIAT have shown that even if a patient reaches a “plateau” of recovery, more progress is still feasible. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that CIAT’s advantages endure over time. However, changes only seem to occur when a patient is receiving intensive therapy. Recent research has looked at combining medication therapy with constraint-induced aphasia therapy, which increased the therapeutic advantages.

Medication

Pharmaceuticals are additionally thought of as an effective treatment for expressive aphasia in addition to intensive speech therapy.

Considering how recent this field of study is, extensive research is still being done on it.

The following medications have been recommended for use in treating aphasia, and control studies have looked at how effective they are.

- Bromocriptine – acts on Catecholamine Systems

- Piracetam – mechanism is not entirely known, but it most likely interacts with several receptors, including glutamatergic and cholinergic ones.

- Cholinergic drugs (Donepezil, Aniracetam, Bifemelane) – act on acetylcholine systems

- Dopaminergic psychostimulants: (Dexamphetamine, Methylphenidate)

Piracetam and amphetamine, which may stimulate brain plasticity and result in an improved potential to improve language function, have demonstrated the greatest effects. It has been shown that piracetam is most beneficial when started as soon as a stroke occurs. It has been far less effective when used for chronic conditions.

According to several research, bromocriptine improves verbal fluency and word recall when used in conjunction with treatment rather than by itself. Its use appears to be limited to non-fluent aphasia as well.

Chronic aphasia has been linked to possible benefits from donepezil. No research has proven beyond a reasonable doubt that any medicine is a successful aphasia therapy. Furthermore, no research has revealed a particular medicine to be effective for language rehabilitation. The recovery of language function and other motor skills following drug use has demonstrated that the improvement is caused by an overall rise in neural network plasticity.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation

Magnetic fields are utilized in transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to generate electrical currents in specific brain areas. The treatment is a non-invasive, painless way to stimulate the cortex. TMS inhibits the inhibition process in certain regions of the brain. The targeted region of the brain may be reactivated and afterward recruited to make up for lost function by blocking the inhibition of neurons by external influences. According to research, people who get routine transcranial magnetic stimulation have better object-naming abilities than those who do not. Additionally, studies indicate that this benefit lasts even after TMS therapy has finished. However, some individuals do not see any appreciable benefit with TMS, indicating the need for more study on this therapy.

Differential Diagnosis

- Anterior circulation stroke

- Cardioembolic stroke

- Central pontine myelinolysis

- Cerebral venous thrombosis

- Dementia in motor neuron disease

- Dissection syndrome

- Frontal lobe syndrome

- Glioblastoma multiforme

- Head injury

Recovery

Some persons who suffer from expressive aphasia may recover significantly and regain a large portion of their language skills. The source and extent of the brain damage must be considered, though.

Language recovery usually reaches its peak after 2 to 6 months if a stroke is the cause. Beyond this stage, advancement is still possible but typically more constrained.

Regardless of the reason, complete recovery frequently requires several months, and it can occasionally even require years, particularly in stroke cases. Depending on their health at the moment, people may require a variety of various sorts of support.

Summary

The most prevalent variety of non-fluent aphasia is expressive aphasia. Although they can understand speech and know what they want to communicate, those who have it talk in fragmented phrases. They could avoid little words and speak in brief, straightforward terms.

Expressive aphasia can be brought on by conditions that harm Broca’s region of the brain. The brain’s capacity to translate thoughts into speech becomes impaired by this. The primary form of treatment is speech and language therapy.

FAQs

What is an example of expressive aphasia?

The following are signs and symptoms of expressive aphasia: displays struggling speech or is unable to talk at all. struggles to come up with the right phrases and may link together inappropriate terms (“word salad”) repeatedly utters single words or brief phrases.

What is the difference between aphasia and expressive aphasia?

When you have expressive aphasia, you have difficulty speaking or writing what you want to communicate. Your capacity to read and comprehend speech is impacted by receptive aphasia. You can read words on a page or hear what others are saying, but you have problems understanding what they are saying.

What causes expressive aphasia?

Aphasia often develops slowly as the result of a brain tumour or a degenerative neurological condition, although it can also happen unexpectedly, frequently following a stroke or head accident. Reading, writing, and language comprehension are all affected by the disease.

What are the 3 types of aphasia?

Aphasia: 3 Types

There are three main categories of aphasia:

Broca’s aphasia.

Wernicke’s aphasia.

Global aphasia.

What is the characteristic of expressive aphasia?

Treatment, causes, and symptoms of expressive aphasia

When a person has expressive aphasia, they may be able to hear speech but have trouble communicating clearly. Although it takes effort, people with expressive aphasia can talk. They frequently use brief phrases and may omit minor linking words from sentences.

Is Broca’s expressive aphasia?

Expressive aphasia

A kind of aphasia called expressive aphasia, commonly referred to as Broca’s aphasia, is characterized by a partial loss of the capacity to create language (spoken, physical, or written), however, understanding typically remains unaffected. An individual with expressive aphasia will speak with effort.

References

- Expressive aphasia: Symptoms and treatment. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/expressive-aphasia

- Expressive aphasia. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Expressive_aphasia

- Broca Aphasia. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK436010/