Meniscus Root Repair Surgery

What is a Meniscus Root Repair Surgery?

Meniscus root repair surgery is a procedure to repair a torn meniscus root. The meniscus is a piece of cartilage that acts as a cushion between the bones of the knee joint. The meniscus root is the part of the meniscus that attaches to the bone.

Meniscus root tears can cause pain, swelling, and instability in the knee. Surgery is often recommended for young, active patients with meniscus root tears. The goal of surgery is to restore the normal function of the meniscus and improve knee stability.

Meniscus root repair surgery is usually performed arthroscopically, meaning through small incisions around the knee. The surgeon inserts a camera and surgical instruments into the knee joint to repair the torn meniscus root.

What is a Meniscus Root?

Two roots of the meniscus in the knee are in the role of spreading weight equally on the tibia’s surface. The stability and functionality of the knee are dependent on these roots. They serve as the meniscus’ sites of attachment to the knee bone. The meniscus would push out of the knee without the support of these crucial roots and would be unable to transfer weight.

The main and supplemental fiber attachment sites found on the meniscal roots contribute significantly to the native attachment sites and root attachment forces.

Medial meniscus posterior root attachment (MPRA)

The most repeatable medullary landmark, the medial tibial eminence (MTE), is 9.6 mm posterior and 0.7 mm lateral to the MPRA. Additionally, the MPRA’s center point can be noticed 8.2 mm directly anterior to the most proximal aspect of the PCL tibial attachment point and 3.5 mm laterally to the medial cartilage inflection point, which serve as two additional acceptable landmarks.

Lateral meniscus posterior root attachment (LPRA)

The lateral tibial eminence (LTE) is 4.2 mm medial and 1.5 mm posterior to the LPRA. The center of the LPRA is also 12.7 mm directly anterior to the most distal part of the PCL tibial connection and 4.3 mm medial to the lateral cartilage inflection point.

Medial meniscus anterior root attachment (MARA)

Along the anterior intercondylar crest of the anterior slope of the tibia, the MARA is inserted. According to reports, the MARA’s center is 27.5 mm anteriorly from the medial tibial eminence apex and 18.2 mm anteromedial from the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tibial footprint center. When treating tibial fractures with intramedullary nails, the MARA is in danger.

Lateral meniscus anterior root attachment (LARA)

Given the significant overlap between the ACL footprint and the LARA, the LARA averaged 140.7 mm2. In addition, the LARA location was 7.1 mm from the closest border of the lateral articular cartilage, 14.4 mm from the apex of the lateral tibial eminence, and 5.0 mm anterolateral of the ACL footprint’s center. Therefore, during ACL tibial tunnel reaming, there is an important possibility of accidental damage to the LARA.

Meniscal Root Injury

For the health of the joint, the root attachments of the posterior horns of the medial and lateral meniscus are crucial. When they are damaged, the joint is loaded as though the damaged side’s meniscus were removed. The development of bone edema, insufficiency fractures, early onset of arthritis, and the failure of associated cruciate ligament restoration grafts are all common in these patients.

What are the symptoms of a Meniscus root injury?

A meniscus root tear can cause rapid and severe discomfort. A meniscus root tear may be indicated by knee discomfort, particularly in the back and medial side of the knee, or by the patient hearing a “pop” at the time of injury. The patient’s move could be different and they may limp and be unable to bear weight on the injured knee.

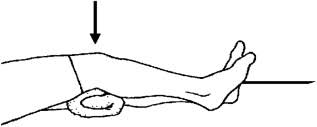

Description of a Meniscus Root Repair

Meniscus root repairs are done by isolating the root, attaching at least two sutures into the remaining meniscal attachment, and then attempting to move the root back into a more anatomic position. The meniscus posterior horn may occasionally need to be freed from scar tissue in order to be relocated. It is crucial to try to restore the meniscus to a position where there won’t be much tension on the repair with the knee range of motion because these restorations are still fairly flimsy with current technology.

A small diameter tunnel, typically 5 millimeters in size, is reamed to the meniscal root attachment site after sutures have been inserted arthroscopically into the meniscal attachment. The sutures are then drawn down the tunnel and secured over a button on the anterior cortex of the tibia. To ensure that the physical therapist does not flex them harder within this time frame, one should evaluate the range of motion that can be performed at that moment in time in a “safe zone.”

Biomechanics

Shiny white fibers (SWF) and supplemental fibers have been reported to significantly increase the ultimate failure strengths of the posteromedial, posterolateral, and anteromedial roots in biomechanical investigations. However, it is still debatable whether or not these fibers should be regarded as a component of the meniscal root attachment. In light of this, it has been claimed that some surgical procedures may fail to fully restore knee biomechanics because they do not include these fibers during restoration.

For the tibiofemoral joint’s long-term health, it has also been observed that a non-anatomic repair has serious effects. A non-anatomic transtibial pull-out repair of the medial meniscal roots, anchored just 3-5 mm medial, significantly reduced the contact area, and raised the mean contact pressure under tibiofemoral loading. Anatomic repair is therefore required to lessen the negative variables accelerating osteoarthritis progression. Anatomic repair is therefore required to lessen the negative variables accelerating osteoarthritis progression.

Due to its capacity to recreate the tibiofemoral contact pressures and contact area at time zero, the two-tunnel transtibial pull-out repair approach has gained popularity among doctors. Due to the biological effect created by tunnel drilling permitting the expression of growth factors and progenitor cells from bone marrow, the transtibial pull-out procedure has also been proposed to have the additional benefit of accelerated meniscal healing. The breakdown of the meniscus-suture interface was cited, as the primary factor in root displacement rather than a “bungee effect,” which has been a source of concern regarding the micromotion of the meniscal root induced by long-length suture structures.

Imaging

Meniscal root tears and associated diseases are best diagnosed with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). In a recent prospective level II study, utilizing a 3.0 T MRI, the diagnostic sensitivity was 77%, the specificity was 73%, the PPV was 22%, and the NPV was 97%; MPRT had a greater sensitivity. T2-weighted sequences containing coronal, sagittal, and axial images are frequently used to look for meniscal root damage. When an MPRT is suspected, an MRI should be performed to assess three key symptoms:

- The ghost sign, which is the absence of a normal meniscus signal in the sagittal plane.

- Linear high signal intensity perpendicular to the meniscus at the meniscal root (radial tear) in the axial plane.

- A meniscal root with a vertical linear defect (truncation sign).

When combined, these three symptoms have been shown to have a high sensitivity and specificity. On axial, coronal, and sagittal MRI planes, nearly perfect intra- and interobserver reliability was also demonstrated for MPRT diagnosis.

Extrusions larger than 3 mm on mid-coronal imaging are strongly linked to meniscal root rips, severe meniscal degeneration, and articular cartilage degradation. In the presence of posterior meniscal tears, ipsilateral tibiofemoral compartment bone marrow edema and insufficiency fractures are frequently observed.

Treatment

Depending on the extent of the damage, when the injury occurred relative to surgical intervention, and the state of the articular cartilage, the meniscal root may require a variety of treatments. Surgery is used to repair damaged joints in order to delay the onset of OA and restore joint contact pressures and joint kinematics. As a result, patients with diffuse Outerbridge grades 3–4 are not candidates for surgical repair; however, individuals with focal chondral deficits who wish to reduce their symptoms might think about it. Non-operative treatment, partial meniscectomy, and repair are the most often used meniscal root tear treatments.

Non-Operative Treatment

There are very few situations in which a root tear should not be treated surgically given the latest research on the role of the posterior meniscal roots in maintaining hoop stresses, normal knee kinematics, and normal contact loading, as well as excellent post-operative patient-reported outcomes and proven surgical techniques. Non-operative therapy is typically an option for elderly people with high-grade and diffuse OA (Outerbridge 3-4). Some of the symptoms can be treated symptomatically with analgesics (oral or topical), activity moderation, and/or an unloader brace.

Surgical treatment

Meniscus damage and OA should be avoided whenever possible by attempting anatomic repair of the meniscal root, with the exception of situations where the patient is a poor surgical candidate (significant comorbidities or advanced age), has diffuse Outerbridge grade 3 or 4 OA of the ipsilateral compartment, non-symptomatic chronic meniscal root tears, and/or has significant limb malalignment unless it is concurrently corrected. The two methods of repair that are most frequently employed are transtibial meniscal root repair and suture anchor repair.

Suture anchor repair

Suture anchor repair, using one suture anchor with two sutures via an all-inside approach, can be used to treat medial meniscal root injuries. For an MPRT, a high posteromedial portal is used to place an anchor at the meniscal root anatomic footprint. Two vertical sutures are then used to reattach the root. The majority of patients who had this technically challenging procedure have grade 3 medial collateral ligament injuries.

Transtibial pull-out repair

There are many options for fixing medial and lateral posterior root injuries with transosseous sutures. Depending on the pattern of the meniscal root tear, the course of treatment may vary slightly. For this specific procedure, sutures are inserted through the meniscal root, retrieved through tunnels drained in the proximal tibia, and then knotted over a post, button, or bridge of the anterior tibia bone. Numerous meniscal suture configurations with various biomechanical characteristics have been proposed, including two basic stitches, a horizontal mattress stitch, modified Mason-Allen (MMA), and two modified loop sutures.

Two straightforward sutures, however, have apparently been shown to cause the least root displacement, have greater stiffness, and do not differ noticeably from the more intricate (MMA) suture. In an effort to more accurately duplicate the anatomical footprint and improve biological healing, single-tunnel and double-tunnel methods have been described. In comparison to screw and washer fixation, button fixation is preferable since it is simpler to perform and poses a lower risk of causing soft tissue irritation.

Preferred technique

The preferred method is a two-tunnel transtibial pull-out repair with two straightforward sutures tied over a cortical button. Standard anteromedial (AM) and anterolateral (AL) parapatellar portals are created together with any additional anteromedial (AM) or anterolateral (AL) portals that may be required. On the tibial plateau, the planned site for root reattachment is decorticated using a curette.

Using an ACL or meniscal root guide, a drill pin with a cannulated sleeve is placed in the back of the footprint, followed by a drill hole with a cannula positioned about 5 mm in front of the previous one. The drill pins are removed after the tunnel placements are confirmed to be accurate, and two simple sutures—one anterior and one posterior—are then inserted into the meniscus root using a suture passing device through either an anterior or posteromedial portal, depending on the device.

Once the sutures have been extracted, they are tied around a button on the AM or AL face of the tibia and inserted into the respective tunnels.

Post-Operative Treatment for Meniscus Root Repair

According to a normal meniscus root repair, the progression of range of motion is more constrained, typically limiting patients to 0-60 or 0-90 degrees range of motion for the first 4 weeks before gradually increasing range of motion as tolerated. Patients may begin weight-bearing at 6 weeks, but they should wait at least 5 to 6 months before performing in any important squatting, squatting while lifting, or sitting cross-legged. At six weeks after surgery, they may begin using a stationary bike and progressively remove themselves off crutches.

General Guidelines

- Toe Touch weight bearing for six weeks while using crutches and a brace

- No flexion of the knee past 90 degrees for the first four weeks.

- Avoid abduction leg raises or straight leg raises initially after medial meniscus surgery or lateral meniscus repair.

- No hamstring or hip extensions for six weeks.

Phase I: Maximum Protection Phase (Weeks 1-6):

For ambulation, the patient should be TTWB with two crutches and the brace locked at 0 degrees.

At 2 weeks post-op, the brace may be drop-locked up to 90 grades for seating

Exercises:

- Patellar mobs

- Calf stretch

- Hamstring stretch

- Ankle pumps

- independent quad sets with optional electrical stimulation

- leg raises & abduction/adduction/extension leg lifts per surgical protection

- Multi-angle quad isometrics

- Clamshells for gluts and hip abductors

- Up to 90 degrees of active aided knee flexion while seated at the top of the table.

- Add LAQs for quad 90–30 knee flexion after two weeks.

- Start pool therapy in chest-deep water after three weeks: A unilateral stance, forward walking, half squats, heel raises, and SLR flexion and abduction

- At week 3 add weight shifts

Phase II: Moderate Protection (Weeks 7-8):

Gradually wean from crutches and discontinue the use of the brace as long as the patient

exhibits good quad control.

Exercises:

- Heel slides to improve the degree of movement as tolerated

- Bike- start with no resistance

- Terminal knee extending with theraband antagonism to start

- Initiate remaining straight leg raises (i.e. abduction/adduction/extension leg raises that were

previously held) - Mini squats 0-45 degrees

- Heel raises

- Cone walking for balance

- Progress weight used for LAQ

- To improve terminal quad control, backward walking on a treadmill with an elevation is recommended.

Phase III: Minimal Protection (Weeks 8-11):

Start hamstring and quad strengthening in a more aggressive method.

Exercises:

- Hamstring curls: start prone or on your feet with a cuff weight and work your way up to weight machines.

- Bridges

- Multi-angle hip machine

- Leg press

- Leg extension machine 90-15 degrees

- Wall sits to 60 degrees

- Step ups in multiple planes

- Lateral touchdowns for eccentric control

- Theraband walking

- Smith Press squats to 60 degrees

- Minilunges

- Progress unilateral balance activities

- Elliptical machine

- Range of movement activities to move to the full range of movement

Phase IV: Advanced Phase (Weeks 12-16)

The aim of all strengthening exercises is to increase strength, power, and endurance to the extent that it is tolerated. The importance of functional and pre-sport activities should be continued.

If the orthopedic surgeon gives the all-clear, the patient should go back and start their running and agility program.

Criteria for return to sports:

- jogging and agility program completed without experiencing any pain

- Quad strength 85-90%/ Hamstring strength 90%

- Good proprioception/balance

- Operative testing (functional hop test, forward & lateral excursion testing, lateral touchdowns)

85% of uninvolved leg

Complication

Re-tear is the most frequent problem following meniscus root repair. Even under ideal conditions, up to 20% of patients may experience this. This is most likely caused by a variety of components, such as the extent of the tear, the tissue’s quality, whether the meniscus was freed from scar tissue and forced back into the joint, and the patient’s age, weight, and alignment.

A blood clot, which is typically prevented with some sort of blood thinner, and discomfort around the surgical button and/or surgical knot from the meniscus root tear are possible additional risks. Additionally, the majority of patients will experience some numbness near the surgical incision, but this is not a true effect and usually occurs with any type of surgical incision.

Conclusion

Meniscus root repair surgery is a safe and effective procedure for young, active patients with meniscus root tears. The surgery can improve knee function and stability, reduce pain and swelling, and delay or prevent the development of osteoarthritis.

The recovery period from meniscus root repair surgery can be long, but most patients are able to return to their normal activities within a few months. The risks of surgery are relatively low, but they should be discussed with your doctor before making a decision.

Overall, meniscus root repair surgery is a good option for patients who are looking to improve their knee function and quality of life.

FAQs

At what age should a meniscus root repair be considered?

Age should not be taken into consideration while repairing the meniscus root. The quality of the cartilage is the most important aspect as one ages. Patients who were 70 and 71 years old, respectively, and who had meniscus root rips that I had successfully treated are among my happiest patients. One patient who started in a wheelchair and was diagnosed with an insufficiency fracture and spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee (SONK) as a result of the root rupture has successfully resumed her normal activities six years following the meniscus root repair, including cycling and hiking. There is also no minimum age for meniscus repairs, with some root repairs being performed on kids as young as 6 or 7. To prevent arthritis, these younger patients in particular need to consider a meniscus root repair as soon as possible.

Where does pain from a meniscus root tear typically occur?

Because a meniscus root tear happens near the back of the knee, the majority of patients with one experience pain when squatting and undergoing deep knee flexion. Being that the meniscus is such an important shock absorber, more diffuse pain over the inside of the knee that worsens over time can be especially dangerous as it may indicate that the cartilage is wearing out quickly, that one has an insufficiency fracture, or that one is experiencing spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee. In order to confirm that a patient may have a meniscus root tear during the clinical examination because many patients do not have important joint line pain like a typical meniscus tear, it is common practice to have the patient stand up and squat down. Many patients with meniscus root tears report experiencing a pop in the back of their knees while performing crouching tasks like floor cleaning, gardening, installing carpet, or plumbing. The standard description of someone who experiences a meniscus root tear is this mechanism of injury and the description of a pop.

If a meniscus root repair fails, what options are there?

Assessing the cause of the failure and the degree of underlying arthritis is necessary to decide whether a revision root repair is required. It has been suggested that a revision root repair may not be necessary if the patient has or has developed severe arthritis, which is typically classified at Kellgren-Lawrence grades 3 or 4. However, if one’s cartilage surfaces are still mostly intact and the meniscus tears again or is put in an unnatural posture, an effort at a revision repair should be attempted. To maximize the chance of healing following the revision root repair procedure, it’s important to ensure that the meniscus has been carefully released from scar tissue and that sutures or the best material for meniscus root restoration, UltraTape is used.

What is an “iatrogenic” meniscus root tear?

An iatrogenic meniscus root tear occurs when the meniscus root is torn from the bone during the drilling of a tunnel for an ACL or PCL reconstruction. For each of the four meniscal attachments in the knee, iatrogenic meniscus root tears have been described. We have written on a few of these, pointing out that a PCL tunnel that is too close to the joint might separate the posterior horn of the medial meniscus and cause medial compartment arthritis. To reduce the risk of an iatrogenic root tear during ACL and PCL procedures, it is crucial to be aware of where the meniscal attachments are located.

What is a meniscus root bony avulsion repair?

Meniscus root tears frequently involve the fracture of a fragment of bone from the tibia in younger patients. In radiology, this is referred to as a “bony ossicle.” The type 5 meniscus root tear repair procedure is similar to the other ways with the exception that the bone piece needs to be tapped off and shaved down so that it may be pulled back into the location where it was avulsed from. For a bone avulsion root repair, placing sutures or UltraTape on either side of the tear and pulling it down into tunnels should be a safe and effective technique. In patients with open growth plates, it might be necessary to either consider removing the sutures once the meniscus root repair has healed or to think about positioning the tunnels and suture repair above the growth plate so that it does not cross the plate and may raise the risk of a growth plate arrest.

References

Beaufils, P., & Verdonk, R. (2010). The Meniscus. Springer Science & Business Media.

Boutin, R. D., Fritz, R. C., & Marder, R. A. (2014). Magnetic resonance imaging of the postoperative meniscus. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Clinics of North America, 22(4), 517–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mric.2014.07.007

Cristiani, R., Rönnblad, E., Engström, B., Forssblad, M., & Stålman, A. (2017). Medial meniscus resection increases and medial meniscus repair preserves anterior knee laxity: a cohort study of 4497 patients with primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 46(2), 357–362. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546517737054

Krych, A. J., Bernard, C. D., Leland, D. P., Camp, C. L., Johnson, A. M., Finnoff, J. T., & Stuart, M. J. (2019). Isolated meniscus extrusion associated with meniscotibial ligament abnormality. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, 28(11), 3599–3605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-019-05612-1

Krych, A. J., Reardon, P. J., Johnson, N. R., Mohan, R., Peter, L., Levy, B. A., & Stuart, M. J. (2016). Non-operative management of medial meniscus posterior horn root tears is associated with worsening arthritis and poor clinical outcome at 5-year follow-up. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, 25(2), 383–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-016-4359-8

Owens, B. D., & Tabaddor, R. R. (2019). Meniscus Injuries, An Issue of Clinics in Sports Medicine, E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Roemer, F. W., Kwoh, C. K., Hannon, M. J., Hunter, D. J., Eckstein, F., Grago, J., Boudreau, R. M., Englund, M., & Guermazi, A. (2016). Partial meniscectomy is associated with an increased risk of incident radiographic osteoarthritis and worsening cartilage damage in the following year. European Radiology, 27(1), 404–413. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-016-4361-z

Sari, A., Günaydın, B., & Dinçel, Y. M. (2019). Meniscus Tears and review of the literature. In IntechOpen eBooks. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.82009

Strauss, E. J., & Jazrawi, L. M. (2020). The management of meniscal pathology: From Meniscectomy to Repair and Transplantation. Springer Nature.