Coronary Artery Disease (CAD)

What is Coronary artery disease (CAD)?

Coronary artery disease (CAD), also known as ischemic heart disease (IHD), refers to a group of diseases that includes stable angina, unstable angina, myocardial infarction, and sudden cardiac death. It is within the group of cardiovascular diseases of which it is the most common type.

A common symptom is chest pain or discomfort which may travel into the shoulder, arm, back, neck, or jaw. Occasionally it may feel like heartburn. Usually, symptoms occur with exercise or emotional stress, last less than a few minutes, and improve with rest. Shortness of breath may also occur and sometimes no symptoms are present. In many cases, the first sign is a heart attack. Other complications include heart failure or an abnormal heartbeat.

Risk factors include high blood pressure, smoking, diabetes, lack of exercise, obesity, high blood cholesterol, poor diet, depression, and excessive alcohol. The underlying mechanism involves the reduction of blood flow and oxygen to the heart muscle due to atherosclerosis of the arteries of the heart. A number of tests may help with diagnoses including electrocardiogram, cardiac stress testing, coronary computed tomographic angiography, and coronary angiogram, among others.

Ways to reduce CAD risk include eating a healthy diet, regularly exercising, maintaining a healthy weight, and not smoking. Medications for diabetes, high cholesterol, or high blood pressure are sometimes used. There is limited evidence for screening people who are at low risk and do not have symptoms. Treatment involves the same measures as prevention. Additional medications such as antiplatelets (including aspirin), beta-blockers, or nitroglycerin may be recommended. Procedures such as percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG) may be used in severe disease. In those with stable CAD it is unclear if PCI or CABG in addition to the other treatments improves life expectancy or decreases heart attack risk.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Chest pain that occurs regularly with activity, after eating, or at other predictable times is termed stable angina and is associated with narrowings of the arteries of the heart.

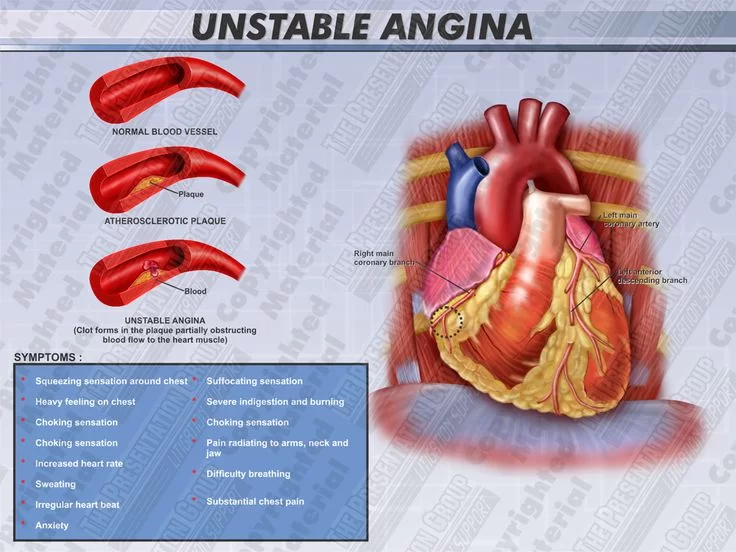

Angina that changes in intensity, character, or frequency is termed unstable. Unstable angina may precede myocardial infarction. In adults who go to the emergency department with an unclear cause of pain, about 30% have pain due to coronary artery disease.

RISK FACTORS

Coronary artery disease has a number of well-determined risk factors. These include high blood pressure, smoking, diabetes, lack of exercise, obesity, high blood cholesterol, poor diet, depression, family history, and excessive alcohol. About half of cases are linked to genetics. Smoking and obesity are associated with about 36% and 20% of cases, respectively. Smoking just one cigarette per day about doubles the risk of CAD. Lack of exercise has been linked to 7–12% of cases. Exposure to the herbicide Agent Orange may increase risk. Rheumatologic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, psoriasis, and psoriatic arthritis are independent risk factors as well.

Job stress appears to play a minor role accounting for about 3% of cases. In one study, women who were free of stress from work life saw an increase in the diameter of their blood vessels, leading to decreased progression of atherosclerosis. In contrast, women who had high levels of work-related stress experienced a decrease in the diameter of their blood vessels and significantly increased disease progression. Having a type A behavior pattern, a group of personality characteristics including time urgency, competitiveness, hostility, and impatience, is linked to an increased risk of coronary disease.

BLOOD FATS

High blood cholesterol (specifically, serum LDL concentrations). HDL (high-density lipoprotein) has a protective effect on the development of coronary artery disease.

High blood triglycerides may play a role.

High levels of lipoprotein a compounds formed when LDL cholesterol combines with a protein known as apolipoprotein.

Dietary cholesterol does not appear to have a significant effect on blood cholesterol and thus recommendations about its consumption may not be needed. Saturated fat is still a concern.

GENETICS

The heritability of coronary artery disease has been estimated between 40% and 60%. Genome-wide association studies have identified around 60 genetic susceptibility loci for coronary artery disease.

OTHERS

Endometriosis in women under the age of 40.

Depression and hostility appear to be risks.

The number of categories of adverse childhood experiences (psychological, physical, or sexual abuse; violence against mother; or living with household members who were substance abusers, mentally ill, suicidal, or incarcerated) showed a graded correlation with the presence of adult diseases including coronary artery (ischemic heart) disease.

Hemostatic factors: High levels of fibrinogen and coagulation factor VII are associated with an increased risk of CAD.

Low hemoglobin.

In the Asian population, the b fibrinogen gene G-455A polymorphism was associated with the risk of CHD.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Micrograph of a coronary artery with the most common form of coronary artery disease (atherosclerosis) and marked luminal narrowing. Masson’s trichrome.

ILLUSTRATION DEPICTING THE CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE

Limitation of blood flow to the heart causes ischemia (cell starvation secondary to a lack of oxygen) of the heart’s muscle cells. The heart’s muscle cells may die from lack of oxygen and this is called a myocardial infarction (commonly referred to as a heart attack). It leads to damage, death, and eventual scarring of the heart muscle without regrowth of heart muscle cells. Chronic high-grade narrowing of the coronary arteries can induce transient ischemia which leads to the induction of a ventricular arrhythmia, which may terminate into a dangerous heart rhythm known as ventricular fibrillation, which often leads to death.

Typically, coronary artery disease occurs when part of the smooth, elastic lining inside a coronary artery (the arteries that supply blood to the heart muscle) develops atherosclerosis. With atherosclerosis, the artery’s lining becomes hardened, stiffened, and accumulates deposits of calcium, fatty lipids, and abnormal inflammatory cells – to form a plaque. Calcium phosphate (hydroxyapatite) deposits in the muscular layer of the blood vessels appear to play a significant role in stiffening the arteries and inducing the early phase of coronary arteriosclerosis. This can be seen in a so-called metastatic mechanism of calciphylaxis as it occurs in chronic kidney disease and hemodialysis. Although these people suffer from kidney dysfunction, almost fifty percent of them die due to coronary artery disease. Plaques can be thought of as large “PIMPLE” that protrude into the channel of an artery, causing a partial obstruction to blood flow. People with coronary artery disease might have just one or two plaques, or might have dozens distributed throughout their coronary arteries. A more severe form is chronic total occlusion (CTO) when a coronary artery is completely obstructed for more than 3 months.

Cardiac syndrome X is chest pain (angina pectoris) and chest discomfort in people who do not show signs of blockages in the larger coronary arteries of their hearts when an angiogram (coronary angiogram) is being performed. The exact cause of cardiac syndrome X is unknown. One explanation is microvascular dysfunction. For reasons that are not well understood, women are more likely than men to have it; however, hormones and other risk factors unique to women may play a role.

DIAGNOSIS

Coronary angiogram of a man

Coronary angiogram of a woman

For symptomatic people, stress echocardiography can be used to make a diagnosis for obstructive coronary artery disease. The use of echocardiography, stress cardiac imaging, and/or advanced non-invasive imaging is not recommended on individuals who are exhibiting no symptoms and are otherwise at low risk for developing coronary disease.

The diagnosis of “Cardiac Syndrome X” – the rare coronary artery disease that is more common in women, as mentioned, is a diagnosis of exclusion. Therefore, usually the same tests are used as in any person with the suspected of having coronary artery disease:

- Baseline electrocardiography (ECG)

- Exercise ECG – Stress test

- Exercise radioisotope test (nuclear stress test, myocardial scintigraphy)

- Echocardiography (including stress echocardiography)

- Coronary angiography

- Intravascular ultrasound

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

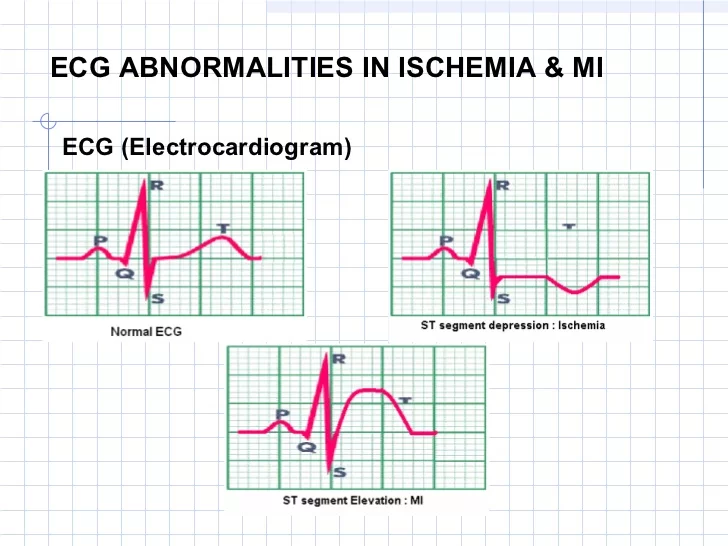

The diagnosis of coronary disease underlying particular symptoms depends largely on the nature of the symptoms. The first investigation is an electrocardiogram (ECG/EKG), both for “stable” angina and acute coronary syndrome. An X-ray of the chest and blood tests may be performed.

STABLE ANGINA

In “stable” angina, chest pain with typical features occurring at predictable levels of exertion, various forms of cardiac stress tests may be used to induce both symptoms and detect changes by way of electrocardiography (using an ECG), echocardiography (using ultrasound of the heart) or scintigraphy (using uptake of radionuclide by the heart muscle). If part of the heart seems to receive an insufficient blood supply, coronary angiography may be used to identify stenosis of the coronary arteries and suitability for angioplasty or bypass surgery.

Stable coronary artery disease (SCAD) is also often called stable ischemic heart disease (SIHD).

ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROME

This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.

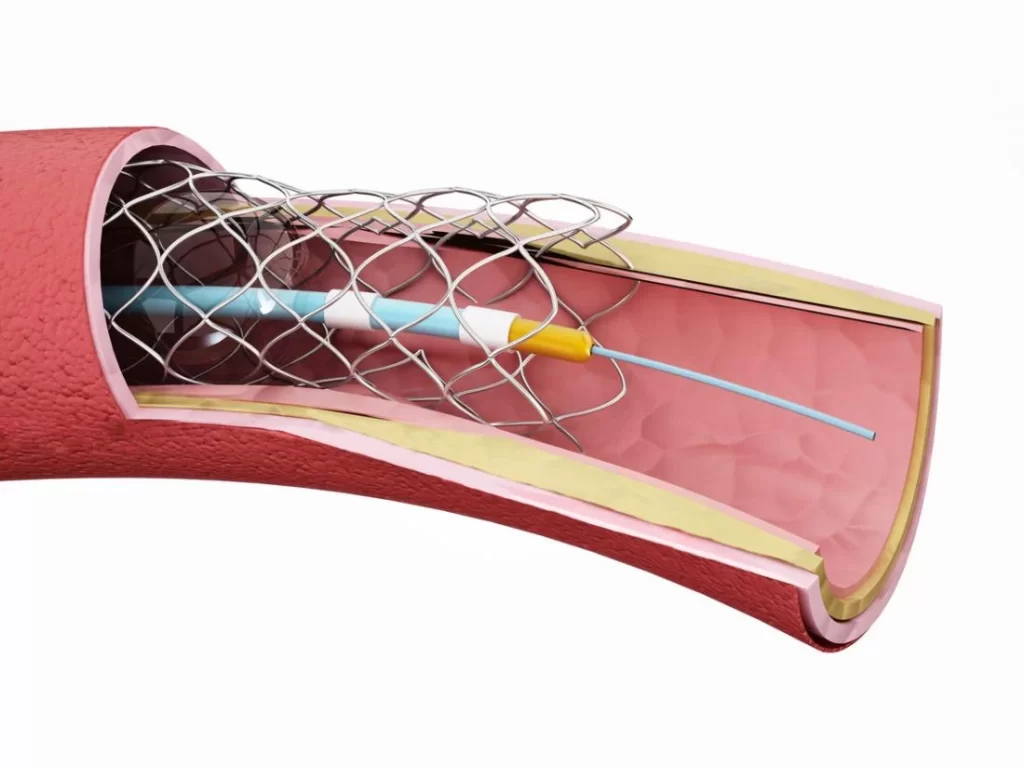

Diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome generally takes place in the emergency department, where ECGs may be performed sequentially to identify “evolving changes” (indicating ongoing damage to the heart muscle). Diagnosis is clear-cut if ECGs show elevation of the “ST segment”, which in the context of severe typical chest pain is strongly indicative of an acute myocardial infarction (MI); this is termed a STEMI (ST-elevation MI) and is treated as an emergency with either urgent coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention (angioplasty with or without stent insertion) or with thrombolysis (“clot buster” medication), whichever is available. In the absence of ST-segment elevation, heart damage is detected by cardiac markers (blood tests that identify heart muscle damage). If there is evidence of damage (infarction), the chest pain is attributed to a “non-ST elevation MI” (NSTEMI). If there is no evidence of damage, the term “unstable angina” is used. This process usually necessitates hospital admission and close observation on a coronary care unit for possible complications (such as cardiac arrhythmias – irregularities in the heart rate). Depending on the risk assessment, stress testing or angiography may be used to identify and treat coronary artery disease in patients who have had an NSTEMI or unstable angina.

RISK ASSESSMENT

This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.

There are various risk assessment systems for determining the risk of coronary artery disease, with various emphasis on the different variables above. A notable example is Framingham Score, used in the Framingham Heart Study. It is mainly based on age, gender, diabetes, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, tobacco smoking and systolic blood pressure.

PREVENTION

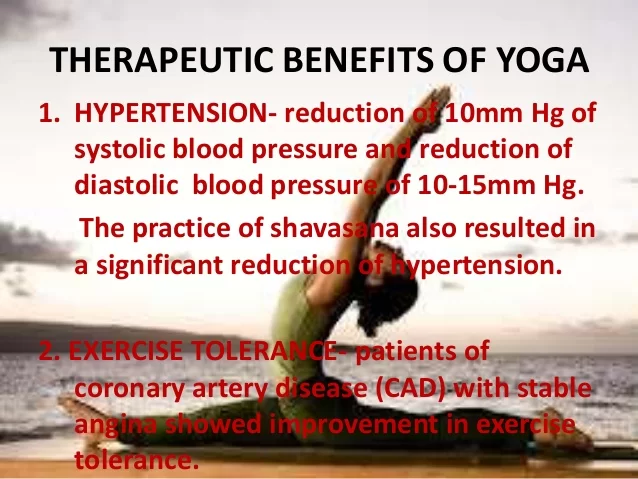

Up to 90% of cardiovascular disease may be preventable if established risk factors are avoided. Prevention involves adequate physical exercise, decreasing obesity, treating high blood pressure, eating a healthy diet, decreasing cholesterol levels, and stopping smoking. Medications and exercise are roughly equally effective. High levels of physical activity reduce the risk of coronary artery disease by about 25%.

In diabetes mellitus, there is little evidence that very tight blood sugar control improves cardiac risk although improved sugar control appears to decrease other problems such as kidney failure and blindness. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends “low to moderate alcohol intake” to reduce risk of coronary artery disease while high intake increases the risk.

DIET

A diet high in fruits and vegetables decreases the risk of cardiovascular disease and death. Vegetarians have a lower risk of heart disease, possibly due to their greater consumption of fruits and vegetables. Evidence also suggests that the Mediterranean diet and a high-fiber diet lower the risk.

The consumption of trans fat (commonly found in hydrogenated products such as margarine) has been shown to cause a precursor to atherosclerosis and increase the risk of coronary artery disease.

Evidence does not support a beneficial role for omega-3 fatty acid supplementation in preventing cardiovascular disease (including myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac death). There is tentative evidence that intake of menaquinone (Vitamin K2), but not phylloquinone (Vitamin K1), may reduce the risk of CAD mortality.

SECONDARY PREVENTION

Secondary prevention is preventing further sequelae of already established disease. Lifestyle changes that have been shown to be effective for this goal include:

- Weight control

- Smoking cessation

- Avoiding the consumption of trans fats (in partially hydrogenated oils)

- Decrease psychosocial stress

- Exercise; aerobic exercise, like walking, jogging, or swimming, can reduce the risk of mortality from coronary artery disease. Aerobic exercise can help decrease blood pressure and the amount of blood cholesterol (LDL) over time. It also increases HDL cholesterol which is considered as “good cholesterol”.Separate to the question of the benefits of exercise; it is unclear whether doctors should spend time counseling patients to exercise. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force found “insufficient evidence” to recommend that doctors counsel patients on exercise but “it did not review the evidence for the effectiveness of physical activity to reduce chronic disease, morbidity and mortality”, it only examined the effectiveness of the counseling itself. The American Heart Association, based on a non-systematic review, recommends that doctors counsel patients on exercise.

TREATMENT

There are a number of treatment options for coronary artery disease:

- Lifestyle changes

- Medical treatment – drugs (e.g., cholesterol-lowering medications, beta-blockers, nitroglycerin, calcium channel blockers, etc.);

- Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG)

MEDICATIONS

Statins, which reduce cholesterol, reduce the risk of coronary artery disease

Nitroglycerin

Calcium channel blockers and/or beta-blockers

Antiplatelet drugs such as aspirin

It is recommended that blood pressure typically be reduced to less than 140/90 mmHg. The diastolic blood pressure however should not be lower than 60 mmHg.

Beta-blockers are recommended first line for this use.

ASPIRIN

In those with no previous history of heart disease, aspirin decreases the risk of myocardial infarction but does not change the overall risk of death. It is thus only recommended in adults who are at increased risk for coronary artery disease where increased risk is defined as “men older than 90 years of age, postmenopausal women, and younger persons with risk factors for coronary artery disease (for example, hypertension, diabetes, or smoking) are at increased risk for heart disease and may wish to consider aspirin therapy”. More specifically, high-risk persons are “those with a 5-year risk = 3%”.

ANTI-PLATELET THERAPY

Clopidogrel plus aspirin reduces cardiovascular events more than aspirin alone in those with a STEMI. In others at high risk but not having an acute event the evidence is weak. Specifically, its use does not change the risk of death in this group. In those who have had a stent more than 12 months of clopidogrel plus aspirin does not affect the risk of death.

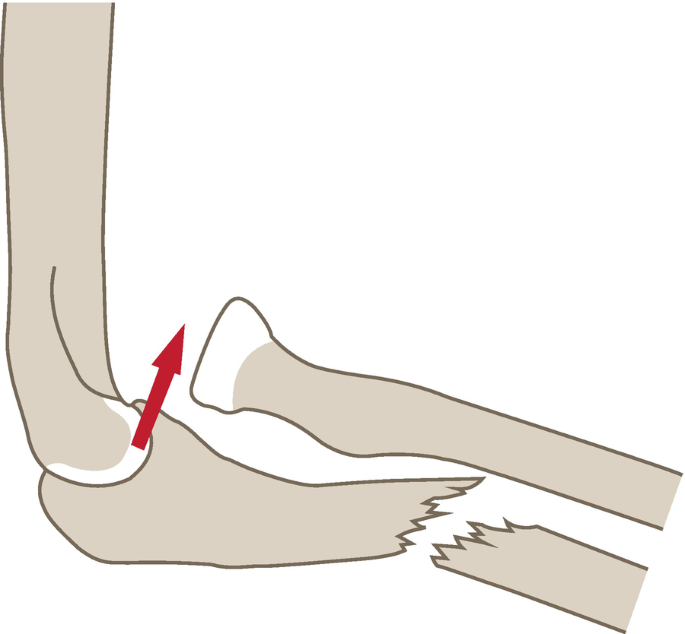

SYRGERY

Revascularization for acute coronary syndrome has a mortality benefit. Percutaneous revascularization for stable ischaemic heart disease does not appear to have benefits over medical therapy alone. In those with disease in more than one artery coronary artery bypass grafts appear better than percutaneous coronary interventions. Newer “anaortic” or no-touch off-pump coronary artery revascularization techniques have shown reduced postoperative stroke rates comparable to percutaneous coronary intervention.

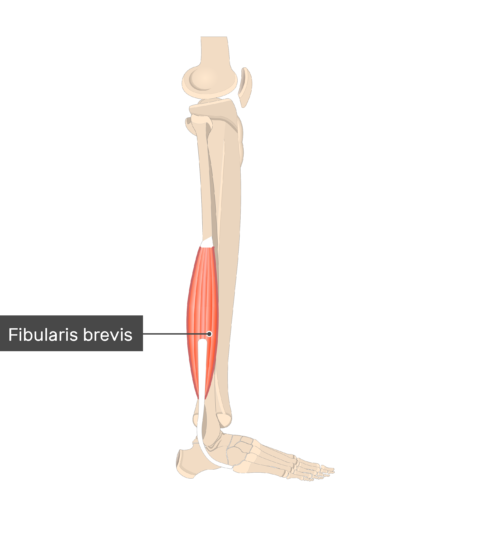

PHYSIOTHERAPY MANAGEMENT

Rehabilitation after a heart attack may take several months or more. The Physiotherapist will teach relaxation techniques, breathing exercises, and exercises to gradually strengthen leg and trunk muscles. Gradually, gentle activity such as walking is introduced. Throughout the programme the Physiotherapist aims to rebuild the person’s confidence, improve exercise tolerance, and teach them to recognize the signs and symptoms of excess exercise.

Regular aerobic exercise decreases the heart rate and blood pressure at rest and during exercise. This helps to reduce the workload on the heart and anginal symptoms may be alleviated. Regular exercise improves muscle function and the ability to take in and utilize oxygen better.

SECONDARY PREVENTION

For CAD the techniques of prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation overlap considerably. Cardiac rehabilitation, which is the long-term treatment of patients who have suffered an episode of severe heart ischemia, is a variant of the same medical care that patients receive in all phases of their CAD. In some medical centers the cardiac rehabilitation program that is prescribed for patients recovering from myocardial infarctions is also offered as preventive therapy for patients at high risk for acute coronary syndromes.

Cardiac rehabilitation is sometimes referred to as secondary prevention. For CAD a key part of both rehabilitation and prevention programs is the reduction of the patient’s atherosclerotic risk factors. Both programs strongly urge smoking cessation. Both programs include supervised weight loss and physical exercise. Both programs offer help in planning nutritionally balanced, low-fat/high-fiber/low-calorie meals. In addition, both programs stress aggressive management of hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia.

TEAM CARE

As with the management of all chronic illnesses, the most effective cardiac rehabilitation programs are organized utilizing a team of physicians, nurses, physical therapists, dieticians, social workers, occupational therapists, and clinical psychologists. Within their own area of expertise, healthcare professionals focus on helping to restore a cardiac patient’s comfort, sense of well-being, and normal daily activities. At the same time each worker aims to reduce specific risk factors to prevent future episodes of ischemia (Graham et al., 2008).

Individual Medical and Social Profiles

Cardiac rehabilitation programs are individualized, and they are planned using a medical and social profile of the patient.

When a rehabilitation team takes over the care of a cardiac patient, they begin by compiling a medical and social history. Besides the standard health history, the team needs to know the details of the patient’s normal daily home, work, and recreational activities. The physical examination information in the profile should include ECG recordings at rest and during exercise. At some point in the program, stress test results are added to the profile and can be used to set exercise guidelines.

With a profile in hand, the team members then divide the tasks and formulate programs in the various areas of rehabilitation care.

SUPPORTIVE AND PROTECTIVE MEDICATIONS

A physician monitors the overall rehabilitation program. Among the physician’s other responsibilities is the adjustment of the patient’s supportive and protective medications.

After a serious episode of heart ischemia, patients will be taking a number of medications. A typical drug regimen includes a statin (with the goal of lowering LDL cholesterol blood levels to 70 mg/dl), a beta-blocker (to ease the work of the left ventricle), and aspirin and clopidogrel (to reduce the risk of clots). As previously mentioned, recent studies have shown that the benefits of combined aspirin and clopidogrel therapy may not outweigh the increased risks of bleeding.

If patients have a poorly functioning left ventricle, they may also be taking an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin-receptor blocker. When a patient continues to have hypertension on the existing drug and lifestyle regimens, a thiazide diuretic is added.

SMOKING CESSATION

Smoking is dangerous for patients who have had an MI. Health professionals need to tell patients who smoke that stopping will cut in half their risk of dying from another ischemic episode.

Clinicians are encouraged to take five steps—the Five A’s—with their patients who smoke:

- Ask. Ask the patient if they smoke.

- Advise. Strongly advise quitting.

- Assess. Ask the patient whether they are ready to quit.

- Assist. Help to formulate a workable smoking cessation plan, including medications and regular interactions with a counselor.

- Arrange. Take steps to put the plan into action: organize the necessary medications, counseling, and follow-up visits.

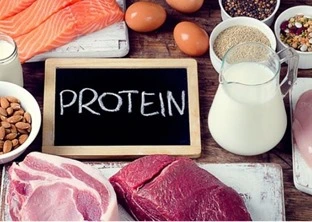

- Healthy Diet

- People eat to maintain energy stores and to provide the materials with which their bodies can repair themselves.

- People also eat out of habit, to alleviate stress and discomfort, and as a compulsion.

Eating that fulfills psychological or emotional needs is not always heart-healthy eating. Many cardiac patients eat out of habit and in response to psychological or emotional stress. These patients need guidance and support when trying to improve their diet.

DIETICIAN

Ideally, a dietician will be part of the cardiac rehabilitation team. Dieticians can help plan meals that:

- Meet the rehabilitation goals

- Patients can afford

- Patients will prepare and eat

- Rehabilitation Goals

- A major rehabilitation goal is to keep blood levels of LDL cholesterol and triglycerides low and levels of HDL cholesterol high. Diets that help to meet these goals are low in saturated fats (<7% of daily calories), have minimal trans fats, and have about 25 g of dietary fiber daily for women and 38 g for men (Am. Diet. Assoc., 2008).

Other dietary advice includes:

- Drinking excess alcohol can raise blood pressure, an atherosclerotic risk factor.

- Salt and certain salt substitutes can contribute to hypertension, especially in those patients with a sensitivity to excess sodium.

- Excess body weight is an atherosclerotic risk factor, so diets should be calorie-controlled.

- Saturated fats should be replaced by monounsaturated fats, polyunsaturated fats, and omega-3 fatty acids (found in oily fish).

- Fruits, vegetables, and grains are recommended.

- Dietary Counseling Programs

- A dietary counseling program begins with the dietician seeing each patient individually. The dietician takes a dietary history and measures the patient’s height, weight, and waist circumference. Patients are then given diaries in which to record all their food and drink intake for five days.

Patients mail or email their diaries to the dietician, and at the next visit, the dietician suggests specific ways that the patient can improve what and how they eat. Regular follow-up visits continue. At each visit, the patient’s height, weight, and waist circumference are measured, the patient’s progress is charted, and specific dietary recommendations are suggested. This diet rehabilitation program should continue until the patient has found a stable, healthy eating routine.

WEIGHT MANAGEMENT

Excess weight is a heart stressor and an atherosclerotic risk factor, so weight reduction is an important component of cardiac rehabilitation for overweight patients. Heart-healthy weight goals are:

- BMI <25 kg/m2 (To calculate BMI Click Here)

- Waist circumference <102 cm (40 in) in men and <90 cm (35 in) in women

- To lose weight, a person must eat fewer calories. People should maintain a nutritional balance while they reduce their caloric intake, and crash diets should be discouraged. By itself, exercise rarely leads to significant weight loss, but exercise can be an important weight loss aid.

For weight reduction and weight maintenance, regular one-on-one sessions with a dietician are usually the most successful tools. Experienced dieticians can help patients to devise a healthy reduced-calorie eating plan that the patient can stick with for the long term.

EXERCISE

Well-planned exercise training can restore many patients to a normal or near-normal lifestyle; therefore, at some point in their rehabilitation, most patients should be encouraged to participate in a formal exercise program.

INELIGIBLE PATIENTS

Some cardiac patients will not yet be sufficiently stable, mobile, or resilient to begin the exercise component of cardiac rehabilitation. Ineligible patients include those with:

- Worrisome ischemic symptoms (eg, unstable angina, significant resting ST-segment displacements, BP drop >20 mm Hg during episodes of angina)

- Heart rhythm or conduction problems (eg, uncontrolled tachycardia, atrial arrhythmias, ventricular arrhythmias, third-degree heart block)

- Severe aortic stenosis

- Uncompensated heart failure

- Recent thrombi (eg, from thrombophlebitis)

- Uncontrolled high blood pressure (systolic >200 mm or diastolic >110 mm Hg)

- Uncontrolled diabetes

- Recent heart infections or inflammation (endocarditis, myocarditis, or pericarditis)

- Acute systemic illness or fever

- Acute metabolic problems

- Physical problems that prohibit the exercise

- Medically supervised exercise can be started for most other cardiac patients, including those who are stable following an MI, a coronary reperfusion procedure, or a heart transplant.

STRUCTURED EXERCISE REHABILITATION

To many people, cardiac rehabilitation is synonymous with post-heart attack exercise programs. The exercise component of cardiac rehabilitation reconditions a patient’s musculoskeletal and cardiovascular systems as well as strengthening the heart.

Reconditioning begins in the hospital. Supervised programs then continue for many months. The final goal is for the patient to develop an independent exercise plan that will last for years.

PHASE I: THE HOSPITAL

Exercise rehabilitation can begin as soon as patients are medically stable. Breathing exercises and leg exercises get patients to use their muscles, and these exercises help to re-establish the patient’s confidence that it will be safe to become active again. As the patient heals, assisted walking and light physical therapy can be added. By day four, patients are usually able to walk for 5 to 10 minutes in the corridors 3 to 4 times/day.

PHASE II: AFTER DISCHARGE

Following discharge from the coronary care unit, a reconditioning program is begun. This usually includes having the patient walk indoors on a level floor at a speed that does not raise the patient’s pulse >20 beats/minute above its resting rate. Patients should be reassured that they may fatigue easily.

Over 4 to 6 weeks, patients who are recovering well should be encouraged to increase gradually the total distance they walk until they are walking a total of 3 miles/day. Patients are asked to keep a diary of their daily exercise and the occurrences of any problems, and the physical therapist checks the diary regularly.

PHASE III: SUPERVISED EXERCISED PROGRAMME

When they have been medically cleared by their physician, patients can begin a 6- to 12-month program of regular, supervised exercise. Often, the physician will perform a symptom-limited stress test to establish the patient’s initial exercise capacity for the exercise program.

One commonly followed rehabilitation plan offers supervised exercise programs in 8-week sessions of 2 to 5 classes per week. The intensity of exercise is increased slowly over the sessions.

The main cardiac rehabilitation exercises are aerobic (walking on treadmills, stationary bicycling)—and the intensity of exercise is limited by the patient’s heart rate or feeling of fatigue (perceived exertion). Exercising to 60% to 75% of their maximum heart rate is a typical goal for cardiac patients. (A rough calculation of maximum heart rate is 220 minus the patient’s age.)

Each session begins with 5 to 15 minutes of gentle exercise to decrease peripheral vascular resistance. Patients then undertake 5 to 30 minutes of aerobic exercise. On their physician’s advice, some patients should have ECG monitoring during the exercises. Classes end with a 10-minute cool-down period.

PHASE IV: CONTINUED INDEPENDENT EXERCISE

The effects of supervised programs will fade unless patients continue to exercise regularly. Some patients have the self-discipline to devise and stick to a life-long independent exercise regimen. Many patients are more successful when they enroll in structured exercise programs, which can be found at community centers in most cities. After the formal cardiac rehabilitation program ends and the patient is exercising under their own direction, physicians should check on the patient’s lifestyle at each medical visit and should encourage their patients to remain active.

RESUMING NORMAL DAILY ACTIVITIES

The goal of cardiac rehabilitation is to enable patients to resume a normal life. Patients can be fearful after a heart attack, and they will need specific advice as to how much daily exercise they should attempt. When to return to sexual activities is often on patients’ minds, although they may hesitate to ask. Physicians should introduce the subject and offer a simple guide: one common rule is that people can resume sexual activities when they can walk up and down two flights of stairs without any cardiac symptoms.

The physical therapist supervising a patient’s exercise program is usually able to recommend a realistic level of daily activity for a patient. When daily tasks are beyond a patient’s ability, doing the tasks more slowly can often make them manageable.

Patients should wait to resume driving a car for 4 weeks after an MI and 6 weeks after heart surgery. As they ease into driving independence, patients should begin by driving with a companion and avoid long trips or heavy traffic.

PSYCHOLOGICAL AND EMOTIONAL HELP

Patients who worry about suffering another serious ischemic event can feel overwhelmed, and they often need help making realistic decisions about their lifestyles. Many patients become overly timid, anxious, or depressed. Some patients deny the seriousness of their heart disease. Other patients become angry.

Few patients are able to manage these emotions without help. Physicians should be proactive by probing for clues that their patients might be suffering emotional or psychological distress. Because unapparent emotional and psychological problems can become disabling, all patients should be offered the opportunity to talk with a mental health professional.

6 Comments