ATRIOVENTRICULAR SEPTAL DEFECT

INTRODUCTION

Atrioventricular Septal Defect (AVSD) is a congenital heart condition characterized by abnormal openings in the septum between the heart’s atria and ventricles. This defect can lead to the mixing of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood, potentially causing various health issues and requiring surgical intervention. Understanding AVSD is crucial for both medical professionals and patients dealing with this condition.

Congenital heart diseases affect about 8 to 10 children per 1000 live births and it is estimated the occurrence of 28,846 new cases per year in Brazil, where, on average, 23,077 surgical procedures are needed per year.

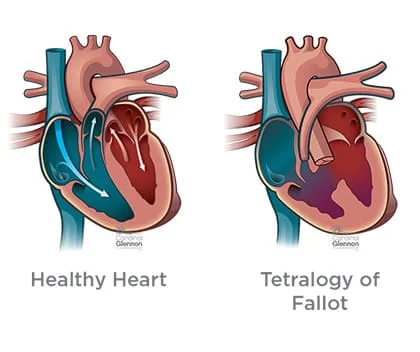

The most common congenital heart diseases in the study of Miyague et al. were cyanotic anomalies such as ventricular septal defect (30.5%), atrial septal defect (19.1%), patent ductus arteriosus (17% ), pulmonary valve stenosis (11.3%) and aortic coarctation (6.3%), while the most common cyanotic anomalies were tetralogy of Fallot (6.9%), transposition of great vessels (4.1%), tricuspid atresia (2.3%) and total anomalous pulmonary veins drainage (2%).

Children with congenital heart disease often develop changes in respiratory mechanics. In addition, heart surgery associated with cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) also leads to a number of respiratory complications. Thus, physiotherapy in the pre-and postoperative period has as its main objectives pulmonary reexpansion, airway clearance, and guidance for those responsible for the prevention of these complications.

This review aimed to update knowledge regarding the role of physiotherapy in preoperative and postoperative pediatric cardiac surgery in the prevention of pulmonary complications.

An atrioventricular septal defect (pronounced EY-tree-oh-ven-TRIC-u-lar SEP-tal DEE-fekt) or AVSD is a heart defect affecting the valves between the heart’s upper and lower chambers and the walls between the chambers.

DEFINATION

An atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD) is a heart defect in which there are holes between the chambers of the right and left sides of the heart, and the valves that control the flow of blood between these chambers may not be formed correctly. This condition is also called atrioventricular canal (AV canal) defect or endocardial cushion defect. In AVSD, blood flows where it normally should not go. The blood may also have a lower-than-normal amount of oxygen, and extra blood can flow to the lungs. This extra blood being pumped into the lungs forces the heart and lungs to work hard and may lead to congestive heart failure.

There are two general types of AVSD that can occur, depending on which structures are not formed correctly:

COMPLETE AVSD

A complete AVSD occurs when there is a large hole in the center of the heart which allows blood to flow between all four chambers of the heart. This hole occurs where the septa (walls) separating the two top chambers (atria) and two bottom chambers (ventricles) normally meet. There is also one common atrioventricular valve in the center of the heart instead of two separate valves – the tricuspid valve on the right side of the heart and the mitral valve on the left side of the heart. This common valve often has leaflets (flaps) that may not be formed correctly or do not close tightly. A complete AVSD arises during pregnancy when the common valve fails to separate into the two distinct valves (tricuspid and mitral valves) and when the septa (walls) that split the upper and lower chambers of the heart do not grow all the way to meet in the center of the heart.

PATRIAL OR INCOMPLETE AVSD

A partial or incomplete AVSD occurs when the heart has some, but not all of the defects of a complete AVSD. There is usually a hole in the atrial wall or in the ventricular wall near the center of the heart. A partial AVSD usually has both mitral and tricuspid valves, but one of the valves (usually mitral) may not close completely, allowing blood to leak backward from the left ventricle into the left atrium.

OCCURRENCE

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that about 2,000 babies (1 in 2,120 babies) are born with AVSD every year in the United States.

CAUSES AND RISK FACTORS

The causes of congenital heart defects, such as AVSD, among most babies are unknown. Some babies have heart defects because of changes in their genes or chromosomes. In particular, AVSD is common in babies with Down syndrome, a genetic condition that involves an extra chromosome 21 (also called trisomy 21). Congenital heart defects are also thought to be caused by the combination of genes and other risk factors, such as things the mother comes in contact with in her environment, what she eats or drinks, or certain medications she uses during pregnancy.

DIAGNOSIS

AVSD may be diagnosed during pregnancy or soon after the baby is born.

DURING PREGNANCY

During pregnancy, there are screening tests (also called prenatal tests) to check for birth defects and other conditions. AVSD may be diagnosed during pregnancy with an ultrasound test (which creates pictures of the baby using sound waves), but whether or not the defect can be seen with the ultrasound test depends on the size or type (partial or complete) of the AVSD. The healthcare provider can request a fetal echocardiogram to confirm the diagnosis if AVSD is suspected. A fetal echocardiogram is an ultrasound of the baby’s heart which shows more detail than the routine prenatal ultrasound test. The fetal echocardiogram can show problems with the structure of the heart and how well the heart is working.

AFTER BABY IS BORN

During a physical exam of an infant, a complete AVSD may be suspected. Using a stethoscope, a doctor will often hear a heart murmur (an abnormal “whooshing” sound caused by blood flowing through the abnormal hole). However, not all heart murmurs are present at birth. Babies with a complete AVSD usually do show signs of problems within the first few weeks after birth. When symptoms do occur, they may include

- Breathing problems

- Pounding heart

- Weak pulse

- Ashen or bluish skin color

- Poor feeding, slow weight gain

- Tiring easily

- Swelling of the legs or belly

- For partial AVSDs, if the holes between the chambers of the heart are not large, the signs and

- symptoms may not occur in the newborn or infancy periods. In these cases, people with a partial

- AVSD might not be diagnosed for years.

Symptoms which might indicate that a child’s complete AVSD or partial AVSD is getting worse include

Arrhythmia, is an abnormal heart rhythm. An arrhythmia can cause the heart to beat too fast, too slow, or erratically. When the heart does not beat properly, it can’t pump blood effectively.

Congestive heart failure is when the heart cannot pump enough blood and oxygen to meet the needs of the body.

Pulmonary hypertension is a type of high blood pressure that affects the arteries in the lungs and the right side of the heart.

The healthcare provider can request one or more tests to confirm the diagnosis of AVSD. The most common test is an echocardiogram. This is an ultrasound of the heart that can show problems with the structure of the heart, like holes between the chambers of the right and left side of the heart, and any irregular blood flow. An electrocardiogram (EKG), which measures the electrical activity of the heart, chest X-rays, and other medical tests may also be used to make the diagnosis. Because many babies with Down syndrome have an AVSD, all infants with Down syndrome should have an echocardiogram to look for an AVSD or other heart defects.

TREATMENT

All AVSDs, both partial and complete types, usually require surgery. During surgery, any holes in the chambers are closed using patches. If the mitral valve does not close completely, it is repaired or replaced. For a complete AVSD, the common valve is separated into two distinct valves – one on the right side and one on the left side.

The age at which surgery is done depends on the child’s health and the specific structure of the AVSD. If possible, surgery should be done before there is permanent damage to the lungs from too much blood being pumped into the lungs. Medication may be used to treat congestive heart failure, but it is only a short-term measure until the infant is strong enough for surgery.

Infants who have surgical repairs for AVSD are not cured; they might have lifelong complications. The most common of these complications is a leaky mitral valve. This is when the mitral valve does not close all the way so that it allows blood to flow backward through the valve. A leaky mitral valve can cause the heart to work harder to get enough blood to the rest of the body; a leaky mitral valve might have to be surgically repaired. A child or adult with an AVSD will need regular follow-up visits with a cardiologist (a heart doctor) to monitor his or her progress, avoid complications, and check for other health conditions that might develop as the child gets older. With proper treatment, most babies with AVSD grow up to lead healthy, productive lives.

PULMONARY COMPLICATIONS IN PEDIATRIC CARDIAC SURGERY

Pulmonary complications of postoperative pediatric cardiac surgery observed: atelectasis, pneumonia, pleural effusion, pneumothorax, chylothorax, pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary hemorrhage, and diaphragmatic paralysis, whereas the first two aforementioned complications are the more common ones.

Atelectasis is defined as the collapse of a certain region of the lung parenchyma. is the most common complication in the postoperative period of cardiac surgery, by worsening oxygenation, decreasing pulmonary compliance, leading to inhibition of cough and pulmonary clearance, and may lead to respiratory failure and increased pulmonary vascular resistance.

Heart surgeries associated with CPB have as adverse effect the increased capillary permeability that causes edema, which results in decreased lung compliance and gas exchange, in addition to leading to airway obstruction, atelectasis, decreased functional residual capacity, and, therefore, hypoxemia.

Stayer et al. assessed the changes in resistance and dynamic pulmonary compliance in 106 children aged less than one year, with congenital heart disease who underwent cardiac surgery with CPB. These variables were measured on two occasions: before the surgical incision with ten minutes of mechanical ventilation and after disconnection of CPB and sternal closure. The authors found that newborns and patients with increased pulmonary blood flow presented preoperatively decreased lung compliance and increased respiratory resistance, whereas after surgery the latter parameter has improved. On the other hand, the infants with normal pulmonary blood flow in the preoperative had decreased lung compliance and developed in the postoperative deterioration of dynamic compliance, however, the pulmonary resistance was not affected. This study showed that heart surgery can alter the respiratory mechanics in newborns and infants.

Among the most common causes of death, it can be highlighted low cardiac output syndrome (48%), followed by lung infections (11%).

Pneumonia is one of the frequent causes of nosocomial infection in the postoperative period of heart surgery and is considered a major cause of morbidity and mortality in this population.

PHYSIOTHERAPY IN PRE- AND POSTOPERATIVE PERIOD

Physiotherapy in the pre-and postoperative period is indicated in pediatric cardiac surgery in order to reduce the risk of pulmonary complications (retention of secretions, atelectasis, and pneumonia) as well as to treat such complications as it contributes to the appropriate ventilation and successful extubation.

In the preoperative, physiotherapy uses techniques of clearance, reexpansion, abdominal support, and guidance on the importance and objectives of physiotherapy intervention for parents escorts, or patients able to understand such guidance. The techniques used by postoperative physiotherapy include vibration in the chest wall, percussion, compression, manual hyperinflation, reexpansion maneuver, and positioning. postural drainage, cough stimulation, aspiration, breathing exercises, mobilization, and AEF (acceleration of expiratory flow).

There are few current studies on the role of physiotherapy in the postoperative of pediatric cardiac surgery, especially those that approach the effectiveness of physiotherapy in the preoperative to prevent pulmonary complications after heart surgery.

Felcar et al. performed a study with 141 children with congenital heart disease, aged varying between one day old to six years, randomly divided into two groups, whereas one of them received physiotherapy in the pre-and postoperative and the other only postoperatively. The study obtained statistically significant differences regarding the presence of pulmonary complications (pneumonia and atelectasis), being more frequent in the group undergoing physiotherapy only postoperatively. Moreover, when the presence of pulmonary complications was associated with other complications regarding the time of hospital stay, such as sepsis, pneumothorax, pleural effusion, and others, the group that received physiotherapy before and after surgery showed a lower risk of developing such complications. These findings demonstrate the importance of preventive action of physiotherapy preoperatively.

According to Kavanagh, the treatment for atelectasis consists of physiotherapy, deep breathing, and incentive spirometry. However, sometimes, atelectasis is difficult to reverse and it is necessary to associate it with another method, as in the case report from Silva et al., in which a child with congenital heart disease underwent heart surgery and developed this pulmonary complication after extubation in the postoperative period and the reversal of this presentation was achieved after the association of respiratory physiotherapy with inhalation of hypertonic saline solution with NaCl at 6%.

Chest radiographs and four physiotherapy sessions lasting 20 minutes were performed daily in this study, using maneuvers of pulmonary reexpansion and bronchial hygiene, bronchial postural drainage, and tracheal aspiration. Immediately before and after physiotherapy inhalation of hypertonic saline solution with NaCl at 6% was associated. The authors found that this association was shown to be effective in this case.

Breathing exercises are indicated in cases of atelectasis due to thoracic or upper abdominal surgery, because they improve respiratory efficiency, and increase the diameter of the airways, which helps to dislodge secretions, preventing alveolar collapse, and facilitating the expansion of the lung and peripheral airway clearance.

Campos et al. analyzed the effect of increased expiratory flow (IEF) on heart rate, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation in 48 children diagnosed with pneumonia. The variables were assessed before physiotherapy, in the first and fifth minutes after physiotherapy. The authors found a statistically significant increase in oxygen saturation and a statistically significant reduction in cardiac and respiratory rate after intervention with IEF and concluded that this physiotherapeutic technique for bronchial hygiene is effective in improving lung function.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

The occurrence of pulmonary complications in the postoperative of heart surgery is quite common, and atelectasis and pneumonia are highlighted among them. Since the frequency of heart surgery in children with congenital heart disease is high, it is important to make use of effective means to prevent, reduce or treat such complications.

Physiotherapy included in the multidisciplinary team contributes significantly to the better prognosis of pediatric patients undergoing heart surgery, as it prevents and treats pulmonary complications by means of specific techniques such as vibration, percussion, compression, manual hyperinflation, reexpansion maneuver, positioning, postural drainage, cough stimulation, aspiration, breathing exercises, IEF and mobilization.

It was observed the effectiveness of physiotherapy in reducing the risk and/or treating pulmonary complications caused by surgical procedures in children with congenital heart disease. Thus, more research is needed to assess the physiotherapy in the pre- and postoperative of pediatric cardiac surgery, by comparing the different techniques used by the physiotherapist in order to minimize the frequent postoperative pulmonary complications.

One Comment