Sotos Syndrome

What is Sotos Syndrome?

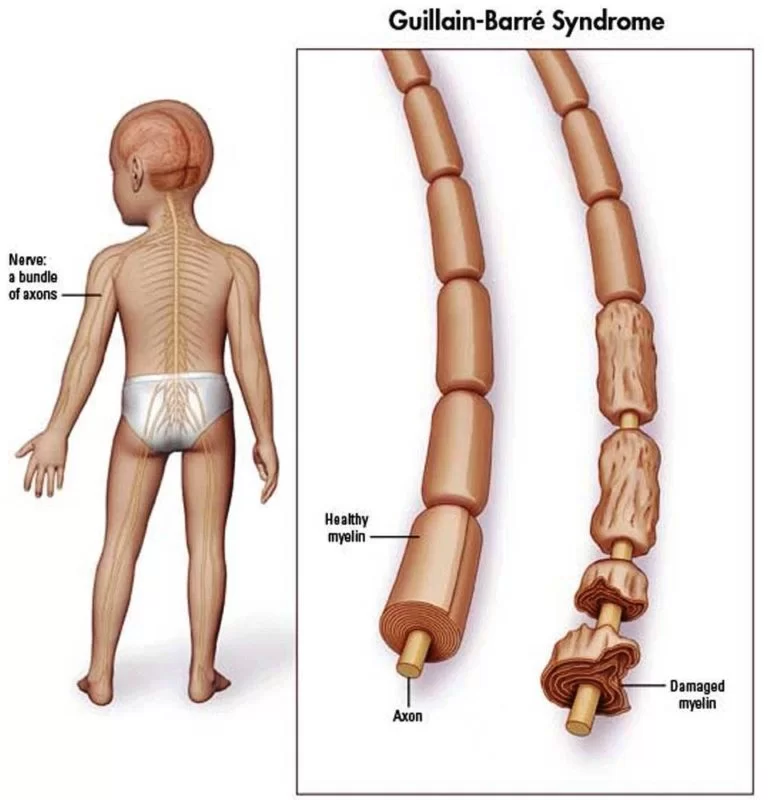

Sotos syndrome, also known as cerebral gigantism, is a rare genetic disorder resulting from a mutation in the NSD1 gene located on chromosome 5. This condition is characterized by excessive physical growth during the early years of life, with affected children typically being larger at birth and exhibiting above-average height, weight, and macrocrania (larger head size) for their age.

Common symptoms associated with Sotos syndrome, which can vary from person to person, include:

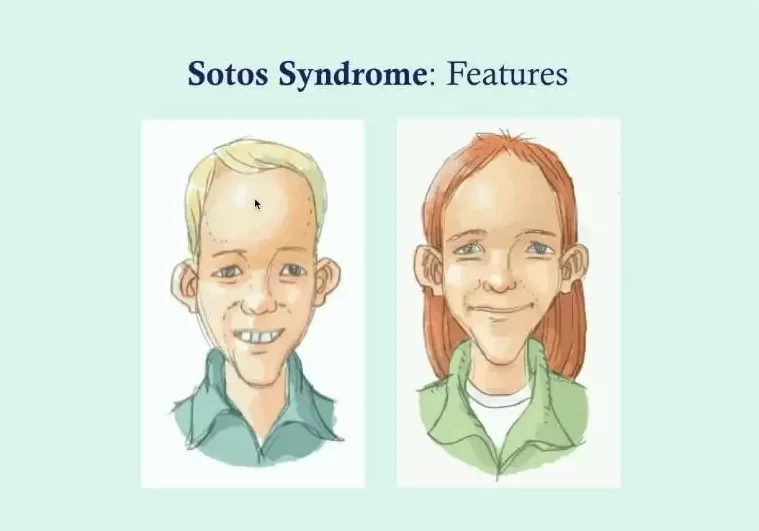

- Macrocephaly: A disproportionately large and elongated head, often featuring a slightly protruding forehead and a pointed chin.

- Gigantism: Oversized hands and feet.

- Hypertelorism: An increased distance between the eyes, causing them to be more widely spaced.

- Facial Features: Eyes with a downward-slanting appearance and other distinctive facial characteristics.

Additionally, individuals with Sotos syndrome may experience:

- Cognitive Impairment: Mild cognitive impairment, which can affect intellectual functioning.

- Delayed Development: Delays in motor skills, cognition, and social interaction.

- Hypotonia: Low muscle tone, contributing to motor challenges.

- Speech Impairments: Difficulty with speech and language development.

- Behavioral Characteristics: Clumsiness, an atypical gait, and occasional displays of unusual aggressiveness or irritability may also be present.

While most cases of Sotos syndrome occur spontaneously (i.e., not inherited), there have been reports of familial instances.

It’s important to note that there is no standardized treatment for Sotos syndrome, and management typically focuses on addressing specific symptoms and needs on an individual basis.

Sotos syndrome is not considered life-threatening, and individuals with this condition can generally expect a normal life span. The initial growth abnormalities associated with Sotos syndrome tend to resolve as growth rates normalize during the first few years of life. Developmental delays may improve during the school-age years, and adults with Sotos syndrome often fall within the normal range for both intellectual abilities and height. However, some coordination difficulties may persist into adulthood.

Sotos syndrome is also sometimes referred to by alternative names, such as Sotos sequence or cerebral gigantism.

Clinical Features of Sotos Syndrome

Sotos syndrome, a complex genetic condition, exhibits a distinctive array of clinical features that evolve over a person’s lifespan. This article provides an in-depth exploration of these features, highlighting the cardinal aspects, major characteristics, and additional associated traits.

Cardinal Features of Sotos Syndrome:

- Distinct Facial Appearance: Sotos syndrome is often typified by a striking facial appearance, most pronounced between ages 1 and 6. Key features include a high, broad forehead that has been likened to an inverted pear, sparse frontotemporal hair, flushed cheeks, down-slanting palpebral fissures, and a pointed chin. Some children may display atypical features, such as up-slanting palpebral fissures or a normal hairline. In adulthood, this facial distinctiveness endures, though the face may elongate, and the chin may become more prominent.

- Learning Disability: A hallmark of Sotos syndrome is the presence of some degree of learning disability, affecting over 90% of individuals. The spectrum of intellectual impairment varies widely, ranging from occasional cases with normal development to children facing profound learning difficulties necessitating lifelong care.

- Overgrowth: From birth, individuals with Sotos syndrome exhibit excessive growth, manifesting as tall stature and macrocephaly. Many babies are born with a length exceeding 2 standard deviations above the mean, although birth weight often remains proportionate. Before puberty, most children with Sotos syndrome experience height and head circumference measurements greater than 2 standard deviations above the mean. Post-puberty, height often normalizes, while significant macrocephaly remains a consistent feature in both children and adults.

Major Features of Sotos Syndrome:

In approximately 15% of Sotos syndrome cases, various medical conditions, known as major features, are observed:

- Advanced Bone Age: Approximately 75% of affected children exhibit advanced bone age. However, it’s important to note that age at assessment and interpretation can influence these findings.

- Cranial Abnormalities: Many individuals with Sotos syndrome present with nonspecific cranial imaging abnormalities. No particular abnormality or pattern of abnormalities is specific to Sotos syndrome, although ventricular dilatation is the most commonly reported feature.

- Neonatal Challenges: Around 70% of infants with Sotos syndrome encounter jaundice and/or feeding difficulties in the neonatal period. Neonatal hypotonia, common in these infants, partly contributes to these challenges. Fortunately, these neonatal problems are typically self-limiting and do not result in long-term issues.

- Cardiac and Renal Anomalies, Seizures, and Scoliosis: Occurring in 15–30% of cases, these conditions vary in type and severity. Cardiac anomalies can range from single, self-limiting anomalies such as ASD (atrial septal defect) to complex anomalies necessitating surgical intervention. The most common renal abnormality is vesicoureteric reflux, with additional anatomical abnormalities like duplex kidneys, absent kidneys, urethral stenosis, and pelvic-ureteric junction obstruction recognized. Sotos syndrome individuals may also experience various types of seizures, including infantile spasms, absence seizures, tonic/clonic seizures, and myoclonic seizures. Scoliosis, ranging from mild to severe, may also be present, potentially requiring bracing or surgical intervention.

Other Features Associated with Sotos Syndrome:

Numerous other clinical features have been documented in individuals with Sotos syndrome. Some, like behavioral problems and constipation, are relatively common and may emerge in more than 15% of cases. Ongoing research may uncover additional features associated with this syndrome.

As our understanding of Sotos syndrome continues to evolve, it is likely that new features, as yet unrecognized, will be reported in affected individuals.

Impact of Sotos Syndrome on Children and Adults:

Sotos syndrome exerts a profound influence on both the physical development and central nervous system of individuals, which in turn affects their behavior and cognitive function. Understanding how the syndrome impacts children and adults is essential for comprehensive care.

Effects on Children:

Sotos syndrome impairs not only physical development but also the central nervous system, resulting in delays in achieving developmental milestones during the early years. These milestones encompass cognitive skills, language development, physical abilities, and social and emotional skills. Cognitive challenges, often manifesting as intellectual disabilities, are common due to the altered functioning of the central nervous system.

Behavioral Symptoms in Children:

Children with Sotos syndrome may exhibit a range of behavioral symptoms, including:

- Anxiety.

- Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

- Autism spectrum disorder.

- Impulsive behaviors.

- Socialization difficulties.

- Tantrums.

These behavioral challenges are often interconnected with the cognitive and developmental aspects of the syndrome.

Differences in Adults:

While children with Sotos syndrome experience rapid growth and heightened stature compared to their peers, this height differential tends to normalize as they transition into adulthood. However, coordination problems may persist into adulthood if not addressed early.

Learning difficulties can vary widely in severity among adults with Sotos syndrome, but not all individuals experience such difficulties. In general, the level of learning difficulty tends to remain relatively stable throughout an individual’s life.

Sotos syndrome is a complex condition that impacts individuals from childhood into adulthood, with a unique constellation of clinical features and a profound influence on development and behavior.

Causes of Sotos Syndrome

- Genetic Origins: Sotos syndrome arises from a genetic anomaly rooted in a mutated NSD1 gene. Remarkably, the Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center indicates that the vast majority, around 95%, of Sotos cases are not inherited. Nevertheless, in cases where a parent has Sotos syndrome, there exists a 50% likelihood of passing the condition on to their offspring.

- Absence of Other Risk Factors: Apart from the genetic component, there are no identified risk factors or causative agents associated with Sotos syndrome. Researchers have yet to unravel the precise triggers behind the genetic mutation responsible for Sotos syndrome or develop strategies for its prevention. The condition’s origin remains a complex and unresolved puzzle within the realm of medical science.

Diagnosing Sotos Syndrome

Diagnosing Sotos syndrome involves a comprehensive evaluation encompassing various aspects, including medical history, clinical assessments, genetic studies, and prenatal diagnosis in certain cases:

- Medical History: The diagnostic process often begins with a thorough examination of the patient’s medical history. This includes investigating whether any other family members have been affected by Sotos syndrome, which can provide valuable insights into the genetic aspects of the condition.

- Clinical Diagnosis: Clinical criteria play a pivotal role in diagnosing Sotos syndrome. These criteria typically encompass:

- Higher-than-normal birth weight and length.

- A larger-than-average head size.

- Neonatal hypotonia (reduced muscle tone in the newborn).

- Distinctive facial features.

- Oversized hands and feet.

- Motor coordination difficulties, clumsiness, and developmental delays that may involve learning and behavioral impairments.

- DNA Studies (FISH Analysis): In some cases, genetic analysis is essential for definitive diagnosis. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis is employed to detect microdeletions and partial NSD1 deletions, accounting for approximately 10-15% of Sotos syndrome cases. In patients without NSD1 abnormalities, genetic testing for NFIX may be considered.

- Prenatal Diagnosis: For cases where Sotos syndrome is suspected during pregnancy, prenatal diagnosis can be pursued. DNA analysis obtained from fetal cells through procedures like amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling may provide insights into the presence of the genetic mutation associated with Sotos syndrome.

- Screening Protocol: A highly efficient denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography (DHPLC) method is utilized for mutation detection in the NSD1 gene. This screening protocol aids in identifying genetic mutations related to Sotos syndrome.

Historically, prior to the identification of NSD1, clinicians relied on additional measures to support the clinical diagnosis of Sotos syndrome, including bone age assessment and cranial imaging. However, these tests have limitations as bone age can be normal or delayed in around 20% of Sotos syndrome cases, and cranial neuro-imaging may yield nonspecific results. Molecular NSD1 testing has emerged as a preferred and precise method for confirming Sotos syndrome diagnoses in the majority of cases. While clinical expertise can still be valuable, molecular testing is often the primary approach.

It’s important to note that individuals who meet the three cardinal criteria for Sotos syndrome but do not exhibit NSD1 abnormalities should still be considered as having Sotos syndrome. However, in such cases, consultation with a clinician experienced in overgrowth conditions is highly recommended before a definitive diagnosis is assigned, especially if the NSD1 test result is normal.

Differential Diagnosis of Sotos Syndrome

Sotos syndrome shares certain phenotypic characteristics with several other clinical conditions, which can sometimes lead to diagnostic challenges. The primary conditions that are frequently confused with Sotos syndrome include Weaver syndrome, Bannayan–Riley–Ruvalcaba syndrome, Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome, and benign familial macrocephaly.

- Weaver Syndrome: Sotos syndrome and Weaver syndrome exhibit considerable phenotypic overlap, especially during infancy when their facial features are similar. However, as children grow older, differentiation becomes more manageable. Classic Weaver syndrome cases tend to have widely spaced palpebral fissures and a rounder facial appearance, contrasting with the typically spaced eyes and prominent chin seen in Sotos syndrome. Molecular analysis can further aid in distinguishing these conditions, as Weaver syndrome is generally not associated with NSD1 abnormalities.

- Bannayan–Riley–Ruvalcaba Syndrome (BRRS): BRRS is primarily caused by PTEN mutations in about 60% of cases. Similar to Sotos syndrome, it often involves learning disabilities and macrocephaly, and may also be associated with tall stature. Boys with BRRS often exhibit penile freckling, a feature not observed in Sotos syndrome. In later stages, lipomatosis, haemangiomatosis, and manifestations of Cowden syndrome may become apparent. A family history of macrocephaly and learning difficulties is common in families with inherited PTEN mutations, which is unusual in Sotos syndrome. Molecular analysis of NSD1 and PTEN can be instrumental in resolving diagnostic uncertainty in cases with clinical similarities.

- Beckwith–Wiedemann Syndrome (BWS): BWS arises from epigenetic defects of 11p15 and is characterized by overgrowth, abdominal wall defects, and macroglossia (enlarged tongue). Additional features may include ear lobe creases and helical pits, visceromegaly, neonatal hypoglycemia, renal abnormalities, and embryonal tumors. Distinguishing between BWS and Sotos syndrome is often straightforward clinically. Macroglossia, a common feature in BWS, is not reported in Sotos syndrome, whereas characteristic facial features and learning disabilities are nearly universal in Sotos syndrome but rare in BWS. In cases where there is overlapping clinical presentation, molecular analyses at 11p15 and NSD1 can help differentiate between the two conditions. Individuals with overlapping phenotypes should be managed according to their underlying molecular defect: those with 11p15 imprinting defects should be managed as Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome, while individuals with NSD1 abnormalities should be managed as Sotos syndrome.

- Benign Familial Macrocephaly: This condition is characterized by macrocephaly in an individual with a positive family history of macrocephaly and no associated neurological deficits. It lacks consistent additional clinical features. Benign familial macrocephaly likely encompasses various conditions, and the diagnosis is typically reserved for individuals in whom other conditions have been excluded through clinical and/or molecular assessments.

Molecular and Genetic Basis of Sotos Syndrome

Sotos syndrome, a genetic disorder, can be attributed to mutations in the NSD1 gene. The NSD1 gene, which stands for Nuclear receptor SET domain containing protein-1, is equipped with various functional domains, including nuclear receptor interaction domains (NID+L and NID−L), zinc-finger plant homeodomains (PHDI–V), proline–tryptophan–tryptophan–proline domains, a SET (Su(var)3-9, Enhancer of Zeste and Trithorax) domain, an adjacent SET-associated cysteine-rich (SAC) domain, and a C5HCH motif. Despite our limited understanding of NSD1’s functions and its role in causing the Sotos phenotype, it is likely involved in transcriptional regulation through histone lysine residue methylation (H3-K36 and H4-K20, mediated by SET and SAC domains), differential binding via the two nuclear receptor interacting domains (NID+L and NID−L), and chromatin interactions mediated by PHD and C5HCH domains.

NSD1 Mutational Mechanisms:

Multiple mutational mechanisms can impair NSD1 function, encompassing truncating mutations, missense mutations, splice-site mutations, partial gene deletions, and 5q35 microdeletions. Truncating mutations result from small nucleotide insertions/deletions, splice-site mutations, or base substitutions that generate premature stop codons (nonsense mutations). These truncating mutations are dispersed throughout the gene. Disease-causing missense mutations arise from base substitutions within NSD1’s functional domains, primarily clustered toward the gene’s 3′ end, though no specific mutational hotspots exist. Partial gene deletions constitute around 5% of NSD1 abnormalities, frequently involving the deletion of exons 1 and 2 due to the high density of Alu repeats flanking these exons. Some partial gene deletions arise through nonallelic homologous recombination between flanking Alu repeats, while others are likely generated via nonhomologous end joining.

The generation and size of 5q35 microdeletions differ based on the individual’s ethnic origin. Outside Japan, these microdeletions vary in size and primarily result from interchromosomal rearrangements. Conversely, a uniform 1.9 Mb microdeletion, generated through intrachromosomal rearrangements, predominates in Japanese Sotos syndrome cases. This 1.9 Mb deletion likely arises from nonallelic homologous recombination between low-copy repeat elements flanking NSD1. In Japan, a common inversion polymorphism that predisposes to microdeletions might explain the higher 5q35 microdeletion frequency, although the frequency of this inversion outside Japan remains unknown. Notably, the deletion of the paternally derived allele is prevalent in all 5q35 microdeletion cases, irrespective of ethnic origin, partially due to NSD1’s telomeric position, with male recombination rates being higher at the 5q telomere compared to females.

Contribution of NSD1 to Sotos Syndrome:

NSD1 abnormalities are detectable in at least 90% of Sotos syndrome cases. NSD1 defects are uncommon in other human overgrowth conditions, although sporadic cases with NSD1 defects may exhibit clinical overlap with Sotos syndrome and other disorders like Weaver syndrome and Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. In European and American Sotos syndrome cases, intragenic mutations account for 80–85% of cases, while 5q35 microdeletions are responsible for only 10–15%. Conversely, among Japanese Sotos syndrome cases, 5q35 microdeletions predominate, identified in over 50% of affected individuals.

Contribution of Other Genes to Sotos Syndrome:

Approximately 10% of classic Sotos syndrome cases do not exhibit NSD1 abnormalities. These cases share the same phenotype as Sotos syndrome cases with NSD1 abnormalities, suggesting that they may primarily result from concealed NSD1 mutations undetectable with current screening methods. Rare individuals diagnosed with Sotos syndrome or Sotos-like syndrome who have defects in 11p15 or GPC3 have been reported, emphasizing the consideration of other molecular defects in Sotos syndrome cases lacking NSD1 abnormalities. Notably, there have been no reports of classic Sotos syndrome cases with abnormalities in genes other than NSD1.

Genotype-Phenotype Associations:

No correlation exists between mutation position and clinical phenotype, indicating that the broad clinical variability observed in Sotos syndrome is largely independent of genotype. However, 5q35 microdeletion cases are more likely to exhibit severe learning disabilities compared to cases with intragenic mutations and tend to have less pronounced overgrowth. This difference may be attributed to the general effects of microchromosomal defects commonly associated with learning disabilities and short stature throughout the genome. Importantly, deletion of neighboring genes in 5q35 microdeletion cases does not appear to exert specific effects on phenotype, as all features observed in microdeletion cases have also been reported in individuals with intragenic NSD1 mutations.

Inheritance of NSD1 Abnormalities:

The vast majority of individuals with Sotos syndrome lack similarly affected relatives, and extensive NSD1 mutation analyses in unaffected parents confirm that none carry the mutation present in their affected child. This indicates that Sotos syndrome is a fully penetrant, primarily sporadic disorder. Rare familial Sotos syndrome pedigrees, accounting for less than 10% of cases, with NSD1 mutations have been reported. These families often harbor missense mutations, although those with truncating mutations are also known. Within these families, the phenotype can vary. The rarity of familial Sotos pedigrees suggests a very low vertical transmission rate of NSD1 defects, with the underlying reasons not entirely clear.

Treatment of Sotos Syndrome

Genetic Counseling:

Most cases of Sotos syndrome result from de novo mutations, and there have been no reports of affected siblings born to unaffected parents. This suggests a low incidence of germline mosaicism. Therefore, the recurrence risk for unaffected parents is roughly equivalent to the population risk, estimated at approximately 1 in 15,000.

Affected individuals and their families should receive genetic counseling, with an emphasis on an offspring risk of 50%, as is common for other autosomal dominant conditions. It’s worth noting that the observed rate of vertical transmission in Sotos syndrome is notably lower than 50%, primarily because familial cases of Sotos syndrome are rare, comprising less than 10% of all cases. Nonetheless, based on limited experience with adult Sotos syndrome cases who have had children, around 50% of their offspring have been affected. There is currently no apparent evidence of impaired fertility, increased fetal loss, or heightened morbidity/mortality in adulthood associated with Sotos syndrome.

Initial Assessment of Individuals with Sotos Syndrome:

During the initial assessment of individuals with an NSD1 abnormality or a high clinical suspicion of Sotos syndrome, a comprehensive history and examination should be conducted to identify known associations and complications associated with the condition. It’s particularly important to investigate renal or cardiac anomalies that, if left undetected, may lead to significant morbidity. Baseline renal investigations should include dipstick urinalysis, blood pressure measurement, and a renal ultrasound scan. Additionally, a baseline cardiac echocardiogram, cardiac auscultation, and blood pressure measurement are recommended. If abnormalities are detected during these routine investigations, referral to the relevant specialist should be considered.

Surveillance of Individuals with Sotos Syndrome:

Clinical geneticists play a crucial role in making the diagnosis, performing the initial evaluation, and discussing recurrence and offspring risks. They may also assist in coordinating the care of individuals with complex medical issues.

In general, individuals with Sotos syndrome would benefit from an annual review, which can be conducted by a family doctor or general pediatrician, depending on the individual’s age and the severity of their condition. The review should encompass a comprehensive history, a thorough examination (including cardiac auscultation, blood pressure measurement, and a back examination), and a dipstick urinalysis. If any abnormalities are identified, appropriate specialist referrals should be initiated.

Tumor Screening:

Tumor screening is not recommended for individuals with Sotos syndrome. Only a small minority of individuals with Sotos syndrome develop tumors. While there is a slightly increased relative risk of neural crest tumors, sacrococcygeal teratomas, and possibly some hematological malignancies, the absolute risk of tumor development in Sotos syndrome is less than 3%. Furthermore, the reported spectrum of tumor types is diverse and does not include tumors for which validated screening protocols exist. Notably, an extensive review of hundreds of molecularly confirmed Sotos syndrome cases has shown that Wilms tumor is an exceedingly rare occurrence in this population, making Wilms tumor screening unnecessary.

Prognosis of Sotos Syndrome

Sotos syndrome is a lifelong condition for which there is currently no cure. However, the good news is that this condition typically does not pose life-threatening risks, and the outlook for children diagnosed with Sotos syndrome is generally positive, with a normal life expectancy. While individuals with Sotos syndrome may experience symptoms related to the genetic condition, there are various treatments and therapies available to help minimize these symptoms and enhance their overall quality of life.

Your child’s healthcare provider will collaborate closely with you to address any concerns related to Sotos syndrome, providing guidance and support throughout your child’s developmental journey. By working together with medical professionals and taking advantage of available therapies and interventions, individuals with Sotos syndrome can lead fulfilling lives and achieve their full potential.

Distinguishing Sotos Syndrome from Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

Sotos syndrome and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are distinct conditions, although they do share some overlapping symptoms, which can occasionally lead to misdiagnosis. Sotos syndrome is a genetic disorder primarily caused by gene mutations, while ASD is a neurodevelopmental condition that often lacks a clearly identified cause. It’s worth noting that individuals with Sotos syndrome have a higher likelihood of also having ASD compared to those without Sotos syndrome.

Common symptoms shared by both Sotos syndrome and ASD include:

- Cognitive Differences: Both conditions may involve intellectual disabilities, though the severity can vary widely.

- Delayed Language Development: Children with either condition may experience delays in language development.

- Delayed Motor Skills and Coordination: Difficulties with motor skills and coordination can be observed in individuals with both Sotos syndrome and ASD.

- Challenges in Social Settings: Both conditions can result in difficulties when interacting in social situations, including problems with social cues and communication.

- Attention Difficulties: Attention-related issues are not uncommon in both Sotos syndrome and ASD.

- Patterns of Behavior and Routines: Individuals with either condition may exhibit repetitive behaviors or have a strong preference for routines.

The primary distinguishing factor between Sotos syndrome and ASD lies in their impact on physical growth. Sotos syndrome significantly affects growth, causing affected children to grow more rapidly and become taller than their peers of the same age. Additionally, distinctive facial characteristics are often present in individuals with Sotos syndrome.

On the other hand, ASD primarily pertains to neurodevelopmental and behavioral aspects, with no direct effect on physical growth. Therefore, while there can be symptom overlap between the two conditions, the presence of accelerated growth and characteristic facial features is a key indicator of Sotos syndrome, setting it apart from ASD.

Conclusion

Since the discovery of NSD1 haploinsufficiency as the underlying cause of Sotos syndrome in 2002, significant progress has been made in understanding this genetic condition. Researchers have defined the range of mutations within the NSD1 gene, elucidated the complex phenotype associated with Sotos syndrome, and developed diagnostic and management guidelines. However, several critical questions remain unanswered.

One major challenge lies in unraveling the normal functions of the NSD1 gene. While its connection to Sotos syndrome is clear, how the disruption of NSD1’s normal functions leads to the diverse clinical features observed in Sotos syndrome remains a puzzle.

From a clinical perspective, the low rate of vertical transmission, meaning the infrequent inheritance of Sotos syndrome from affected parents to their children, is a phenomenon that still lacks a clear explanation. This aspect is of significant importance to individuals with Sotos syndrome, particularly those with mild learning disabilities, who may contemplate having children in the future. Long-term prospective studies will likely be necessary to shed light on this matter and provide guidance to affected individuals.

Furthermore, gaining a better understanding of the phenotype and long-term outcomes of Sotos syndrome in adults is essential. Currently, there is limited information available in this regard. Longitudinal studies that follow individuals with Sotos syndrome into adulthood will be invaluable for filling this knowledge gap.

While progress has been made in characterizing Sotos syndrome, there is still much to learn about the genetic basis, clinical manifestations, and long-term implications of this condition. Ongoing research and comprehensive, long-term studies will contribute to a deeper understanding of Sotos syndrome and improve the care and support available to individuals living with this condition.

FAQ

What are the symptoms of Sotos syndrome?

An elevated forehead.

An extended, thin face.

Chin with a point.

Eyes with a downward tilt (palpebral fissures).

Lengthened arms.

Hypotonia is a state of weak muscular tone.

Tall height.

What is the IQ of someone with Sotos syndrome?

Although there was a considerable range of reported IQ scores from 21 to 113, the results of the systematic review revealed that the majority of people with Sotos syndrome have intellectual disability (IQ 70)/borderline intellectual functioning (IQ 70-84).

What are the behavioral characteristics of Sotos syndrome?

An intriguing finding was that people with Sotos syndrome were significantly more likely than people with Down’s syndrome to engage in compulsive behaviors, such as cleaning, organizing, rituals, and lining up objects, as well as repetitive speech, such as asking the same questions or signing the same things over and over.

Who is the oldest person with Sotos syndrome?

The patient is depicted in a photographic natural history of Sotos syndrome as a young child (exact age unknown), at about 11 or 12 years old, and at present age 63.

At what age is Sotos syndrome diagnosed?

Diagnosis. Early in life, during infancy or the first few years of life, a diagnosis of Sotos syndrome is made. Sotos testing is not done on newborns, but doctors will undertake it if symptoms are present. The testing process and the onset of symptoms could take months or years.

How do you test for Sotos syndrome?

Due to the two distinct sorts of alterations that Sotos syndrome can cause, testing for it is conducted in two stages. When a gene is sequenced, an error (a different letter in the code) is sought after. This entails reading the gene and checking for typos.

What is the birth weight of a child with Sotos syndrome?

Children with Sotos syndrome frequently have big head circumference (14.5′′ versus typical 13.5′′), body length (23′′ versus normal 20′′), and birth weight (9 lbs. versus 7.5 lbs.) when their birth records are examined. One description of the forehead is that it is excessively big, rounded, and possibly pinched at the temples.

Reference

- Rahman, N. (2007). Sotos syndrome. European Journal of Human Genetics, 15(3), 264-271. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201686

- Sotos Syndrome. (n.d.). National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/sotos-syndrome

- Professional, C. C. M. (n.d.). Sotos Syndrome. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/22177-sotos-syndrome

- Geng, C. (2023, March 3). What to know about Sotos syndrome. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/sotos-syndrome#overview

- Barhum, L. (2022, November 12). What Is Sotos Syndrome? Verywell Health. https://www.verywellhealth.com/sotos-syndrome-4174959

- Sotos Syndrome – Causes, Symptoms, Complications & Prognosis. (2017, June 26). Medindia. https://www.medindia.net/patientinfo/sotos-syndrome.htm#treatment

- Sotos Syndrome | Encyclopedia.com. (n.d.). https://www.encyclopedia.com/science/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/sotos-syndrome