Scapula Bone

Introduction

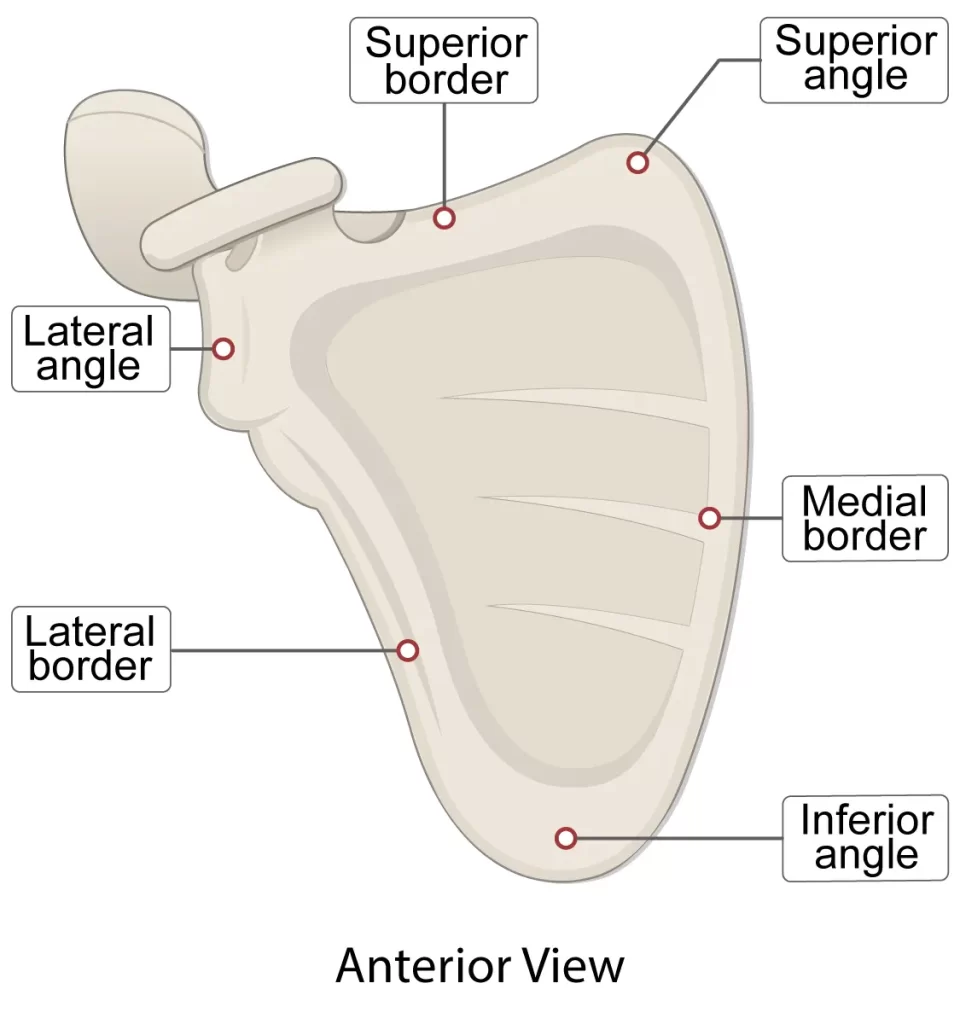

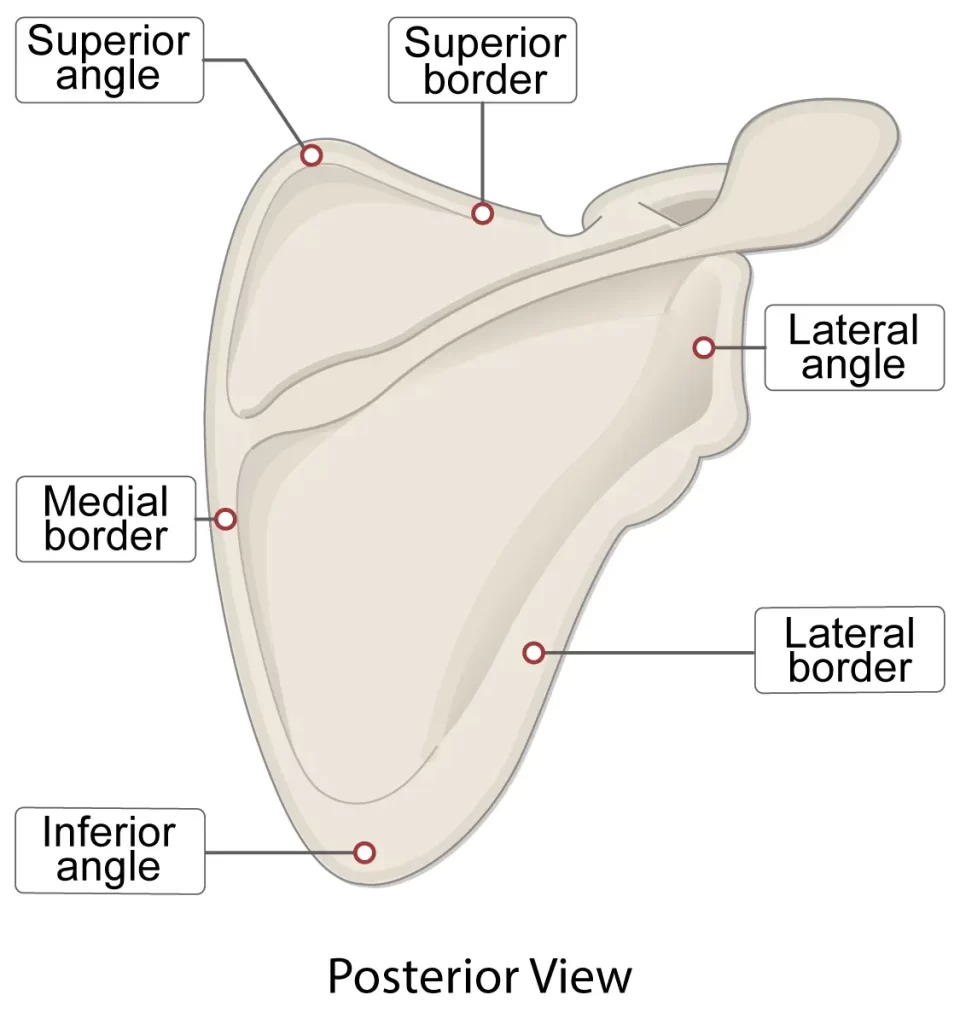

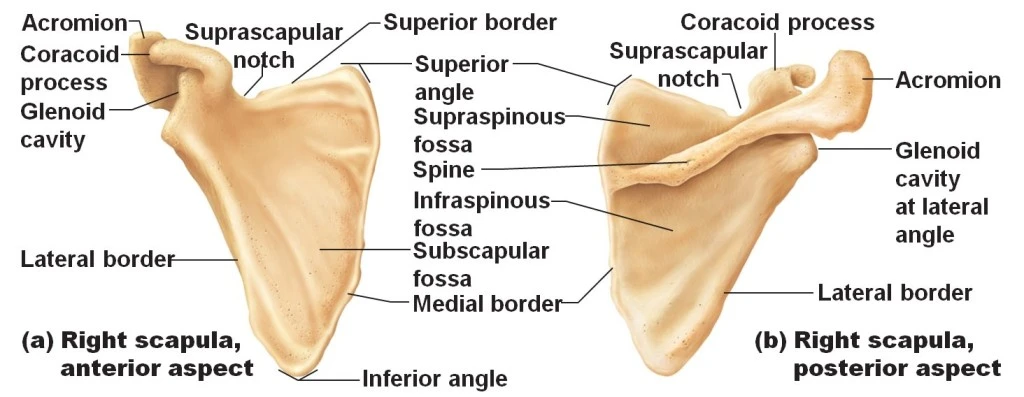

The postero-lateral side of the thoracic cage contains the scapula, a slender, flat triangular bone. It has three borders, three angles, two surfaces, and three processes.

The bone that joins the clavicle with the humerus is called the scapula, or shoulder blade. The Back of the shoulder girdle is formed by the scapula. It is a strong, triangular, flat bone.

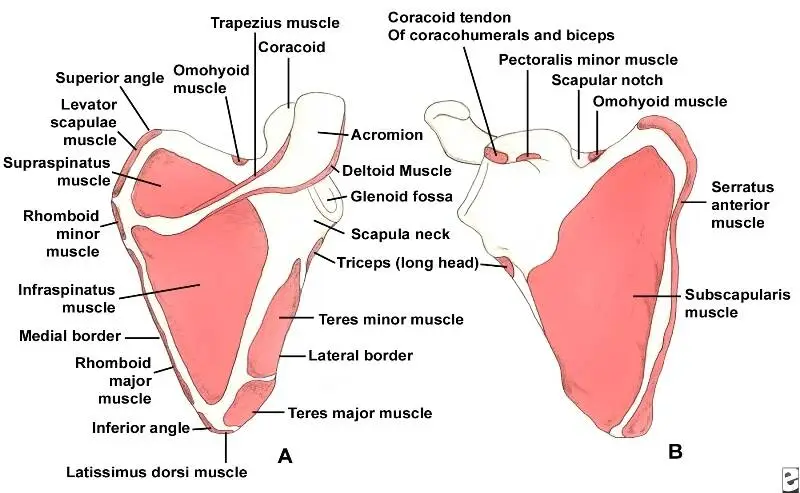

Numerous muscle groups are attached to the scapula. The intrinsic muscles of the scapula consist of the rotator cuff, teres major, subscapularis, teres minor, and infraspinatus.

These muscles attach to the scapular surface and aid in internal and external rotation as well as glenohumeral joint abduction. The deltoid, biceps, and triceps are examples of extrinsic muscles.

The third group of muscles consists of the serratus anterior, rhomboids, trapezius, and levator scapulae. These muscles stabilize the scapula and allow for rotational movements.

The bone that joins the humerus to the clavicle is called the scapula, or shoulder blade. The scapulae are paired, much like their related bones, with each scapula on either side of the body roughly mirroring the other.

It was believed that the name was derived from the Classical Latin term for trowel or little shovel.

In medical terminology, the prefix omo- designates the shoulder blade in compound words.

This prefix comes from the Ancient Greek word who, which meant “shoulder.” It is related to the Latin term humerus, which means “upper arm bone” or “shoulder.”

The back of the shoulder girdle is formed by the scapula. It is a flat, approximately triangular bone that is situated on the posterolateral side of the thoracic cage in humans.

Anatomy

The inferior angle, lateral angles, and superior angles are all located at the apex of a slightly triangular-shaped flat blade that makes up the body of the scapula.

It is said that the scapula has superior, medial, and lateral boundaries.

Scapula is one of the two main vertebrate shoulder girdle bones. They are triangular in shape and located on the upper back of humans, in between the second and eighth rib levels.

The spine, a prominent ridge that separates the scapula into two concave sections called the supraspinous and infraspinous fossae, crosses the posterior surface of the bone obliquely.

The fossae and spine support the muscles that rotate the arm. The process that communicates with the clavicle or collarbone, in front & helps form the upper portion of the shoulder socket is known as the acromion, which marks the end of the spine.

The shoulder joint is formed by the glenoid cavity, a shallow hollow found at the lateral apex of the triangle that articulates with the humerus, the upper arm bone.

The coracoid process, a protrusion like a beak that extends over the glenoid cavity, completes the shoulder socket. Attached to the scapula’s margins are muscles that help move or stabilize the shoulder in response to upper limb movements.

Structure

Three types of muscles attach to the thick, flat scapula on the thoracic wall: the intrinsic, extrinsic, and stabilizing and rotating muscles.

The rotator cuff muscles the subscapularis, teres minor, supraspinatus, and infraspinatus are a part of the intrinsic muscles of the scapula.

These muscles, which adhere to the scapula’s surface, are in charge of humeral abduction as well as the internal and external rotation of the shoulder joint.

The biceps, triceps, and deltoid muscles are examples of extrinsic muscles. These muscles attach to the coracoid process, supraglenoid tubercle, infraglenoid tubercle, and spine of the scapula.

There are multiple activities of the glenohumeral joint that are controlled by these muscles.

The muscles in the third group the trapezius, serratus anterior, levator scapulae, and rhomboid are primarily in charge of stabilizing and rotating the scapula.

These are attached to the scapula’s inferior, superior, and medial margins.

Cancellous tissue is found in the head, processes, and thicker areas of the bone; a thin layer of compact tissue covers the remaining portion.

In humans, the top half of the infraspinatus fossa and the middle part of the supraspinatus fossa, but particularly the former, are typically so thin as to be semitransparent; in certain cases, the bone is occasionally found missing, and the surrounding muscles are only divided by fibrous tissue.

Three borders, three angles, two surfaces, and three processes make up the scapula.

Surfaces

Anterior view

Subscapuler fossa

The anterior surface of the scapula, also referred to as the costal or ventral surface, features a wide indentation termed the subscapular fossa, to which the subscapularis muscle is attached.

The medial two-thirds of the fossa are lined with three longitudinal oblique ridges, while a thicker ridge runs alongside the lateral border, extending upward and outward.

These ridges provide attachment to the tendinous insertions and the surfaces between them to the fleshy fibers of the subscapularis muscle, while the lateral third of the fossa is smooth and covered in the muscle’s fibers.

The transverse depression at the upper part of the fossa is where the bone seems to be bent on its own along a line that passes through the middle of the glenoid cavity at a right angle, forming a significant angle known as the subscapular angle; this gives the bone’s body greater strength due to its arched form, and the peak of the arch supports the acromion and spine.

The origin of the first digitation of the serratus anterior originates on the superior costal region of the scapula.

Posterior view

The dorsal or posterior surface of the scapula, which is arched from above to below, is separated into two uneven sections by the scapula’s spine.

The supraspinous fossa is the area above the spine, and the infraspinous fossa is the area below it. The spinoglenoid notch, which is located lateral to the spinal root, connects the two fossae.

The supraspinous fossa

- The supraspinous fossa, located above the scapula’s spine, is smooth, concave, and wider at the vertebral end than the humeral; the Supraspinatus originates from its medial two-thirds.

- The spinoglenoid fossa, located on the glenoid’s medial edge, is located at its lateral surface. The suprascapular canal, which conveys the suprascapular nerve and vessels, is housed in the spinoglenoid fossa and acts as a connecting tube between the suprascapular notch and the spinoglenoid notch.

The infraspinous fossa

- The infraspinous fossa is significantly larger than the previous one; it has a notable convexity in the center, a shallow concavity toward the vertebral line, and a deep groove that runs from the upper to the lower half at the axillary border.

- The Infraspinatus originates from the medial two-thirds of the fossa; this muscle covers the lateral third.

On the outside of the scapula’s back, there is a ridge. This extends approximately 2.5 cm above the inferior angle from the lower region of the glenoid cavity, downhill and backward to the vertebral boundary.

A fibrous septum that is attached to the ridge divides the Teres major and Teres minor muscles from the infraspinatus muscle.

The groove for the scapular circumflex vessels crosses the upper two-thirds of this narrow surface between the ridge and the axillary border near its center, where the Teres minor attaches.

The inferior angle of the scapula, which gives birth to the Teres major and over which the Latissimus dorsi glides, is the broader, somewhat triangular surface of its lower third.

Often, a few fibers from this region serve as the origin of the latter muscle.

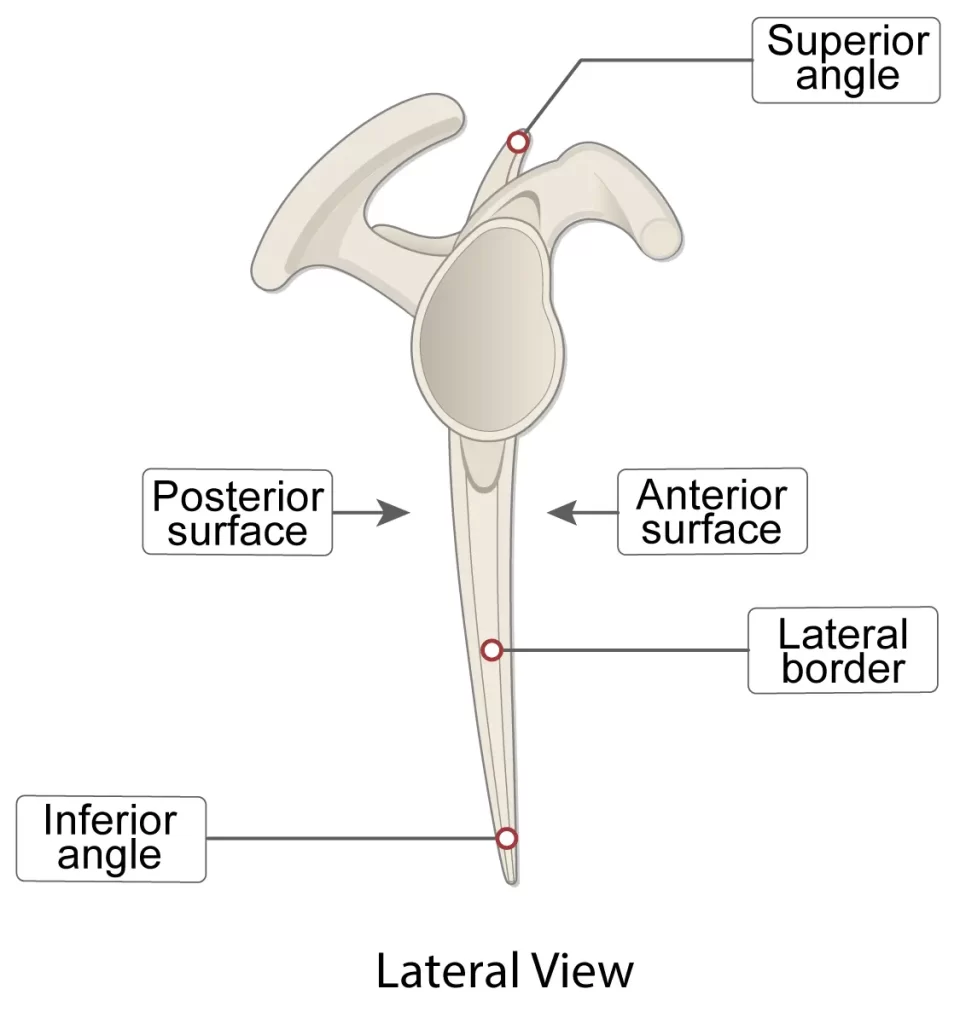

Lateral view

The acromion, a broad, rather triangular or oblong process, is what gives the shoulder its peak. It is flattened from behind and projects laterally at first, then curves upward and forward to overhang the glenoid cavity.

Angles

The superior angle

The trapezius muscle covers the medial or superior angle of the scapula. The intersection of the scapula’s superior and medial margins forms this angle.

At the approximate level of the second thoracic vertebra is where the superior angle is situated. Attachment points for a few levator scapulae muscle fibers are located on the scapula’s thin, smooth, rounded, and somewhat lateral angle.

The inferior angle

The latissimus dorsi muscle covers the inferior angle of the scapula, which is the lowest point on the scapula. As soon as the arm is abducted, it advances and around the chest.

The junction of the scapula’s medial and lateral edges forms the inferior angle. Its posterior, or back, surface is thick and rough, allowing attachment to the teres major and frequently a few latissimus dorsi fibers.

The scapular line is the name of the anatomical plane that runs through the inferior angle vertically.

The glenoid angle

The thickest portion of the scapula is the lateral angle, often called the glenoid angle or the head of the scapula.

It is broad and articulates with the head of the humerus, bearing the glenoid fossa on its articular side. It is pointed forward, laterally, and somewhat upward.

The inferior angle has the largest vertical diameter and is wider below than above. When the cartilage is still young, it covers the surface. The glenoidal labrum, a fibrocartilaginous structure, attaches to the slightly elevated borders of the surface, deepening the cavity.

The long head of the biceps brachii is linked to the supraglenoid tuberosity, a minor elevation at the apex of the muscle.

The anatomic neck of the scapula

The somewhat narrower area that encircles the head and is more pronounced below and behind than above and in front is known as the anatomic neck of the scapula.

Directly medial to the base of the coracoid process is where the surgical neck of the scapula passes.

Borders

The scapula has three boundaries:

The superior border

The thinnest and shortest border is the superior one, which is concave and runs from the base of the coracoid process to the superior angle. In animals, it’s known as the cranial boundary.

The base of the coracoid process contributes to the formation of the scapular notch, a deep, semicircular notch located at its lateral portion. The superior transverse scapular ligament, which occasionally becomes ossified, transforms this notch into a foramen, which allows the suprascapular nerve to pass through.

the attachment to the omohyoideus is possible in the neighboring portion of the superior border.

The lateral or axillary border

Out of the three, the axillary border is the thickest. It starts above at the glenoid cavity’s lower edge and slopes rearward and downward at an oblique angle to the inferior angle.

In animals, it’s known as the caudal boundary.

It starts above at the glenoid cavity’s lower edge and slopes rearward and downward at an oblique angle to the inferior angle.

The long head of the triceps brachii originates from the infraglenoid tuberosity, a rough impression approximately 2.5 cm in length, directly below the glenoid cavity.

A longitudinal groove, which extends to the lower third of this border, lies in front of this and provides the origin of a portion of the subscapularis.

The middle border

The longest of the three borders, spanning from the superior angle to the inferior angle, is the medial border, also known as the vertebral border or medial margin. It’s known as the dorsal boundary in animals.

The medial boundary is linked to four muscles. The anterior lip features a lengthy connection for the serratus anterior.

The levator scapulae (uppermost), rhomboid minor (middle), and rhomboid major (lower middle) are the three muscles that insert along the posterior lip.

Structure and function

One crucial bone for the shoulder joint’s operation is the scapula. It can move the upper limbs in six different ways, allowing for full functional movement: protraction, retraction, elevation, depression, upward rotation, and downward rotation.

The pectoralis major, pectoralis minor, and serratus anterior muscles work together to accomplish protraction. The muscles that perform retraction are the latissimus dorsi, rhomboids, and trapezius. The rhomboid, levator scapulae, and trapezius muscles work together to achieve the elevation.

Gravity and the movements of the latissimus dorsi, serratus anterior, pectoralis major and minor, and trapezius muscles enable depression.

The muscles of the trapezius and serratus anterior are responsible for performing upward rotation.

Gravity, the latissimus dorsi, levator scapulae, rhomboids, and the pectoralis major and minor muscles all contribute to the process of downward rotation.

One of the most flexible and adaptable joints in the human body, the shoulder joint, is fully functional because of the scapula’s six movements.

The winged scapula (See Clinical Significance), in which paralysis of the serratus anterior or trapezius prevents the lifting of the upper extremity above shoulder level, is one illustration of the significance of scapular motion for the whole range of motion of the upper extremity.

Attachments on the Scapula

There are multiple muscles that join directly to the scapula, making the surrounding musculature crucial to the stability of the scapula.

It features a variety of bony projections where muscles, ligaments, and other soft-tissue structures can be attached.

The attachment points of the teres major and levator scapulae are at the inferior and superior angles of the scapula, respectively.

While the serratus anterior attaches to the medial margin of the scapula, the rhomboids major and minor adhere to the medial border.

The anterior surface of the scapula, commonly referred to as the subscapular fossa, is where the subscapularis begins. The posterior surface, also referred to as the infraspinous fossa, is where the infraspinatus connects.

The supraspinatus, infraspinatus, subscapularis, and teres minor are the four muscles that make up the rotator cuff.

These four muscles surround the glenohumeral joint and give it muscular support by forming a musculotendinous cuff.

Muscles on scapula

The scapula’s intrinsic muscles adhere straight to the bone’s surface. The glenohumeral joint is stabilized by these four muscles, which make up the rotator cuff.

Among them are:

- Supraspinatus

- Function: Stabilize the glenohumeral joint and initiate the first 15 degrees of arm abduction.

- Origin: Fossa supraspinous

- Insertion: At the summit of the larger tubercle

- Nerve innervation: Suprascapular nerve(C5, C6)

- The infraspinatus

- Function: Arm lateral rotation, glenohumeral joint stabilization

- Origin: Infraspinous fossa

- Insertion: Teres minor insertion between the supraspinatus and greater tubercle of the humerus

- Nerve innervation: Suprascapular (C5, C6)

- Teres minor

- Function: Arm lateral rotation, glenohumeral joint stabilization

- Origin: The scapula’s neighboring posterior side and lateral/axillary border

- Insertion: The humerus’s inferior side of the larger tubercle

- Nerve innervation: Axillary nerve (C5, C6)

- The subscapularis

- Function: Arm adduction and medial rotation, glenohumeral joint stabilization

- Origin: fossa subscapular

- Insertion: Humeral tubercle, less severe

- Nerve innervation: Subscapular nerves (C5, C6, C7)

Motion at the glenohumeral joint is influenced by the extrinsic muscles of the scapula, which are attached to the scapula’s processes.

Among them are:

- Biceps brachii

- Function: Prevents shoulder dislocation, forearm supination, and significant flexor activation.

- Origin: Short head: coracoid process Long head: tubercle supraglenoid

- Insertion: Forearm fascia and radial tuberosity (as bicipital aponeurosis)

- Nerve innervation: Musculocutaneous nerve (C5, C6)

- Function: Prevents shoulder dislocation and substantial forearm extensor muscle strain.

- Origin: Lateral head: above the radial groove, Medial head: below the radial groove, Long head: scapula’s infra glenoid tubercle

- Insertion: Forearm fascia and ulnar olecranon process

- Innervation: Radial nerve (C6, C7, C8)

- Deltoid

- Function: The arm’s flexion and medial rotation are brought about via the anterior aspect. Arm abduction (up to 90 degrees) is the function of the middle aspect. The arm’s lateral rotation and extension are controlled by the posterior aspect.

- Origin: Acromion, scapular spine, and lateral clavicle

- Insertion: Tuberosity of the Deltoid

- Nerve innervation: Axillary nerve (C5, C6)

The following are scapular stabilizing muscles:

- Trapezius

- Function: During arm abduction (90–180 degrees), upper fibers raise and rotate the scapula. the scapula is retracted by middle fibers. The scapula is pulled inferiorly by lower fibers.

- Origin: Nuchal ligament, spinous processes of C7 to T12, and skull

- Insertion: scapular spine, acromion, and clavicle

- Nerve innervation: Accessory nerve (cranial nerve XI)

- Levator scapulae

- Function: Raises the shoulder blades

- Origin: C1–C4 vertebral transverse processes

- Insertion: Scapula’s medial border

- Nerve innervation: C3, C4, and the dorsal scapular nerve (C5)

Serratus anterior

- Function: facilitates rotation and abduction of the arm (90 to 180 degrees) and secures the scapula into the thoracic wall.

- Origin: The side of the chest, on the surface of the upper eight ribs

- Insertion: Throughout the whole anterior length of the scapula’s medial edge

- Nerve innervation: Long thoracic (C5, C6, C7)

- Rhomboid major

- Function: The scapula retracts and rotates.

- Origin: T2 through T5 vertebral spinous processes

- Insertion: Scapula’s inferomedial boundary

- Nerve innervation: Dorsal scapular nerve (C5)

- Rhomboid minor

- Function: The scapula retracts and rotates.

- Origin: C7 to T1 vertebrae’s spinous processes

- Insertion: Scapula’s medial border

- Nerve innervation: Dorsal scapular nerve (C5)

Additional scapula-attached muscles include:

- Latissmus dorsi

- Function: The upper limb extends, adducts, and rotates medially.

- Origin: The inferior three ribs, the iliac crest, the thoracolumbar fascia, the spinous processes of T6 to T12, and the inferior angle of the scapula

- Insertion: The humerus’s intertubercular sulcus

- Nerve innervation: Thoracodorsal nerve (C6, C7, C8)

- Teres major

- Function: The arm’s adduction and medial rotation

- Origin: The scapula’s posterior surface at its inferior angle

- Insertion: The medial portion of the intertubercular groove

- Nerve innervation: Lower scapular nerve (C5, C6)

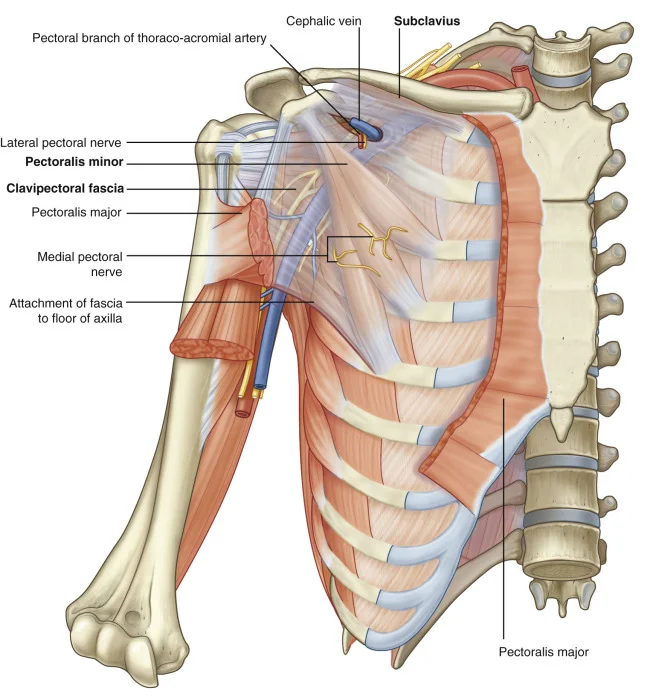

- Pectoralis minor

- Function: Protraction of the scapula and depression of the shoulder

- Origin: Near the corresponding costal cartilages of the third, fourth, and fifth ribs

- Insertion: The coracoid mechanism

- Nerve innervation: Medial pectoral nerve (C8, T1)

- The coracobrachialis

- Funtion: Arm flexion and adduction

- Origin: Process of coracoid

- Insertion: On the medial aspect of the middle of the humerus

- Nerve innervation: Musculocutaneous nerve (C5, C6, C7)

- The Omohyoid

- Function: Pulls down the hyoid bone, which is active during swallowing and speaking.

- Origin: Scapula’s superior boundary

- Insertion: Hyoid’s inferior edge

- Nerve innervation: Ansa cervicalis is innervated (C1, C2, C3)

Ligaments

The glenoid labrum and the shoulder joint capsule are attached to the glenoid cavity’s border.

The acromioclavicular joint capsule is attached to the edge of the facet on the medial aspect of the acromion.

The medial side of the acromion process tip and the lateral border of the coracoid process are where the coracoacromial ligament is attached.

The root of the coracoid process is where the coracohumeral ligament is attached.

The trapezoid portion on the superior aspect and the conoid portion close to the root of the coracoid process is where the coracoclavicular ligament is attached.

The conoid and trapezoid bands, which both offer vertical stability, make up the coracoclavicular ligament. The acromion and coracoid process are joined by the coracoacromial ligament.

The suprascapular nerve is transmitted through a foramen created by the suprascapular ligament, which spans the suprascapular notch. Above the ligament is the suprascapular ligament.

The spinoglenoid notch is crossed by the spinoglenoid ligament. It is supplied by the nerve and suprascapular vessels.

The acromioclavicular ligament offers horizontal support by joining the acromion and distal end of the clavicle.

Bursas

Two main bursae exist:

- Thoracic scapula Bursa, situated amidst the thorax and serratus.

- Between the serratus and the subscapularis is the subscapularis Bursa.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Because of its location and function as an essential part of the shoulder joint, as well as the need for flexibility, the scapular blood supply is complicated.

It is primarily supplied by scapular anastomosis, an anastomosis that occurs between the axillary and subclavian arteries.

The dorsal scapular artery, suprascapular artery, deep scapular artery, circumflex scapular branch of the subscapular artery, and the medial anastomoses with the intercostal arteries are contributing arteries to this anastomosis.

When utilizing the shoulder in its various positions and while lying supine, collateral blood flow is made possible via scapular anastomosis.

The axillary vein, suprascapular veins, and several tiny, highly variable anastomotic tributaries are primarily responsible for the venous drainage of the scapula.

The lymphatic drainage from the left scapula empties into the thoracic duct, whereas the lymphatic drainage from the right scapula empties via the right lymphatic duct.

There are two lymph nodes connected to the scapula: the supraclavicular and axillary lymph nodes.

Nerves

The anterior ramus C5 root, the posterior cord, and the superior trunk are the origins of the dorsal scapular, upper and lower subscapular, and suprascapular nerves, which innervate the scapula. For more information on certain muscle innervations, see the “Muscles” section below.

Biomechanics

During functional elevation, the scapula rotates upward in the frontal plane, tilts posteriorly in the parasagittal plane, and rotates externally in the transverse plane.

For scapulohumeral coordination to function, scapular control is necessary. The humeral clearing that occurs during the acromiohumeral phase of shoulder elevation is the result of posterior tilting.

The acromioclavicular joint is the only joint that connects the scapula to the upper limb. It articulates with the posterior chest wall.

The scapulothoracic joint is the only joint that moves in unison with the acromioclavicular joint, which does not move independently.

The acromioclavicular and sternoclavicular joints are necessary for the mobility of the scapulothoracic joint.

The scapula, clavicle, and humerus work together in the scapulohumeral rhythm, which has a 2:1 ratio, to achieve complete arm elevation. This indicates that the scapula travels one degree for every two degrees that the humerus moves.

The glenohumeral joint allows for 120 degrees of movement, while the scapulothoracic joint allows for 60 degrees of upward rotation, for a total elevation of 180 degrees of the arm.

The clavicle must elevate, retract, and roll posteriorly, whereas the scapula must rotate upward, tilt posteriorly, and rotate externally. Thoracic spine extension is required. The serratus anterior and the upper and lower trapezius are the muscles that work together to facilitate upward rotation.

According to a study, abduction elevation results in greater scapular upward rotation and retraction than flexion elevation. Additionally, they found that during flexion elevation, posterior tilting was at its highest.

Any disruption to this rhythm may lead to restrictions in elevation, impingement, weariness, and instability as well as a reduction in scapulothoracic mobility.

Clinical anatomy

Scapulothoracic abnormalities

The most typical kind is scapular winging. Damage to the long thoracic nerve that innervates the serratus anterior muscle can occasionally result from axillary surgery, such as a mastectomy.

Due to the unopposed action of the rhomboid, levator scapulae, and trapezius muscles, the inferior angle of the scapula protrudes backward and is readily visible through the patient’s skin.

Damage to the dorsal scapular nerve, which supplies the rhomboid muscles, or the spinal accessory nerve, which supplies the trapezius, can also cause scapulothoracic instability.

Winging of the scapula is a milder complication of damage to the dorsal scapular nerve than of a damaged long thoracic nerve.

A depressed and rotated scapula results from injury to the spinal accessory nerve caused by laceration, radiation, or dissection of the neck, as the serratus anterior muscle acts without resistance.

Facioscapulohumeral dystrophy, an autosomal dominant disorder that affects the serratus anterior, rhomboids, trapezius, teres major and minor, pectoralis minor and major, biceps, and triceps muscles, is another factor contributing to scapula winging.

Consequently, the scapula wings and only the deltoid muscle can move the shoulder.

Scapular dysplasia

An aberrant morphology of the scapula, known as scapular dysplasia, can result from either primary or acquired brachial plexus palsy during pregnancy.

The scapula can be viewed as a modular part that originates from the blade, glenoid/coracoid block, and spine/acromion block, among other ossification centers.

Primary dysplasia results in bilateral anatomical alterations due to inadequate ossification of the glenoid. In infants, this causes clicking, instability, or pain; in older people, it causes degenerative changes.

Due to aberrant posterior glenoid cartilage formation, babies with brachial plexus injuries after delivery may also exhibit morphological abnormalities in their scapula.

Shoulder dystocia, an obstructive vaginal birth problem typically defined by impaction of the anterior fetal shoulder against the maternal symphysis pubis, is the most common risk factor for neonatal brachial plexus palsy.

Teens with a history of shoulder pain may exhibit posterior-inferior glenoid dysplasia, which is defined by a silent dislocation of the glenohumeral joint caused by the humeral head sliding posteriorly during internal rotation and elevation of the arm.

On occasion, this is connected to a distinctive dimple on the back of the afflicted shoulder.

Snapping scapula syndrome

There are several muscles that are located in between the ribs and the scapula to help it glide across the chest wall smoothly. Bursae are also present and aid in reducing friction and cushioning the tissue.

The scapulothoracic (or infraserratus; between the serratus anterior muscle and chest wall) and subscapularis bursae (between the subscapularis muscle and serratus anterior muscle) are the two main bursae at the scapulothoracic joint.

The scapulothoracic (or infraserratus; between the serratus anterior muscle and chest wall) and subscapularis bursae are the two main bursae at the scapulothoracic joint.

Osteochondroma, a benign cartilage tumor, is the most frequent cause of lesions on the anterior aspect of the scapula.

The most common cause of scapulothoracic bursitis is overuse of the joint from repetitive arm motions over the head.

Fractures

The scapula is susceptible to fractures much like any other bone. They only account for 0.5 to 1% of all fractures, though, because the scapula is highly protected.

The rib cage and thoracic cavity protect the scapula from the anterior and posterior directions, respectively. There is a lot of soft tissue covering it as well.

As a result, high-impact direct trauma is typically the cause of scapular fractures, and almost all cases are linked to other extremely serious, occasionally numerous, and potentially fatal injuries.

As a result, treatment for scapular fractures is often delayed and the fractures often go misdiagnosed until much later.

Development

The ossification of the scapula occurs from seven or more centers: the body, two coracoid processes, two acromion centers, one vertebral border center, and one inferior angle center.

Around the second month of fetal life, an uneven quadrilateral plate of bone forms directly below the glenoid cavity, signaling the start of ossification of the body.

The scapular spine emerges from the dorsal surface of this plate, which forms the main portion of the bone, around the third month. Before birth, ossification begins as membranous ossification.

The cartilaginous parts would go through endochondral ossification after birth. The scapula experiences membrane ossification in its major portion.

Since some of the scapula’s outer segments are cartilaginous at birth, they will endochondral ossify.

A significant portion of the scapula is osseous at birth, however, cartilaginous structures make up the glenoid cavity, coracoid process, acromion, vertebral border, and inferior angle.

Ossification occurs in the middle of the coracoid process, which usually joins with the rest of the bone around the 15th year after birth, between the 15th and 18th month after birth.

The remaining portions ossify quickly, usually in the following order, between the ages of 14 and 20: first, in the form of a broad scale at the root of the coracoid process; second, in the vicinity of the acromion’s base; third, in the inferior angle and contiguous portion of the vertebral border; fourth, in the vicinity of the acromion’s outer end; and fifth, in the vertebral border.

An extension from the spine forms the acromion’s base, and the two acromion nuclei combine before joining with the spine extension.

The sub-coracoid, a distinct center that emerges between the ages of 10 and 11 and unites between the ages of 16 and 18, forms the top part of the glenoid cavity.

Additionally, the lower portion of the glenoid cavity contains an epiphysial plate, and the tip of the coracoid process often has a distinct nucleus. By the 25th year, these different epiphyses are attached to the bone.

It is possible for the detached segment in some cases of supposed acromion fractures with ligamentous union to have never been united to the rest of the bone.

This is due to either imperfect articulation or failure of bony union between the acromion and spine.

FAQs

What is the normal position of the scapula?

The scapula normally sits between the second and seventh ribs on the posterior thorax, about two inches from the midline.

What is the function of the spine of the scapula?

Operation. It displays three boundaries and two surfaces. Its concave superior surface contributes to the formation of the supraspinatus fossa and gives some of the supraspinatus its genesis.

Where is the scapula located?

The term “shoulder blade” refers to the flat, triangular scapula bone. It is situated on the dorsal surface of the rib cage in the upper thoracic area. To form the shoulder joint, it joins the clavicle at the acromioclavicular joint and the humerus at the glenohumeral joint.

What are the 3 angles of the scapula?

The medial, inferior, and lateral are the three angles of the scapula. One way to describe the scapula is as a triangle bone with three sides and three angles. The scapula has three angles: lateral, inferior, and medial.

What is the anatomy of the scapula?

Anatomy, skeletal features, and purpose of the scapula, or shoulder blade. The scapula, sometimes referred to as the shoulder blade, is a flat, triangular bone that rests on the posterior surface of ribs two through seven in the back of the trunk.

Why is the scapula important?

One crucial bone for the shoulder joint’s operation is the scapula. It can move the upper limbs in six different ways, allowing for full functional movement: protraction, retraction, elevation, depression, upward rotation, and downward rotation.

Reference

- Scapula. (2023, December 31). Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scapula#

- Scapula. (n.d.). Physiopedia. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Scapula

- Cowan, P. T. (2023, August 8). Anatomy, Back, Scapula. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK531475/#:~:text=Introduction,to%20several%20groups%20of%20muscles.

- Scapula | Shoulder Blade, Bone Structure & Muscles. (2023, November 29). Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/scapula

- Joe, N. (2023, September 11). Scapula. Kenhub. https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/scapula

2 Comments