Best Exercises for Winging of Scapula

Strengthening exercises targeting the muscles around the scapula can help improve scapular stability and reduce winging.

What is the winging of the scapula?

The word “winged scapula” (also known as scapula alata) refers to a situation in which the scapula’s muscles are too paralysed or weak to stabilise the scapula.

The scapula’s medial or lateral edges therefore project from the back in a manner akin to wings. Musculoskeletal and neurological disorders are the primary causes of this illness.

Scapula winging can cause significant discomfort, impair scapulohumeral rhythm, cause power loss, and restrict upper extremity flexion and abduction. This crippling illness can make it difficult to push, pull, and lift large things and to carry out ordinary tasks like carrying grocery bags and cleaning one’s teeth and hair.

Clinically relevant anatomy of the winging scapula:

The following anatomical structures are part of the winged scapula:

- Bones:

- Scapula

- Muscles:

- Trapezius

- Serratus Anterior

- Rhomboids

- Levator Scapulae

- Pectoralis Minor

- Latissimus Dorsi

- Nerves:

- Spinal Accessory Nerve

- Dorsal Scapular Nerve

- Thoracicus longus, or long thoraconic nerve

- Brachial plexus

- Musculoskeletal structures related to the winged scapula:

- Trapezius

- Serratus Anterior

- Rhomboids: Rhomboids Major

- Levator Scapulae

- Pectoralis Minor

- Latissimus Dorsi

- Structures connected to the scapula’s neurological wings:

- Trapezius (Pars Descendens)

- Serratus Anterior

- Rhomboids

- Spinal Accessory Nerve

- Dorsal Scapular Nerve

- Thoracicus longus, or long thoraconic nerve

- Brachial plexus

Cause of winging of the scapula:

The winging of the scapula is unusual. Of these, the prevalence of scapular winging resulting from trapezius paralysis is extremely rare and challenging to measure. On the other hand, scapular winging is most frequently caused by serratus anterior paralysis as a result of an iatrogenic injury. The causes of winging, in general, are:

- Anterior Serratus Palsy

- Trapezius Palsy

- Rhomboid Palsy

Epidemiology of Winging of the Scapula:

All of these leading winged scapulas have the following causes:

Traumatic:

- Acute traumas include things like getting a sharp blow to the shoulder in an automobile accident and having your arm suddenly twisted. There have also been reports of it from both professional and recreational athletes participating in a range of sports, such as bodybuilding and weight lifting, archery, ballet, baseball, basketball, golf, gymnastics, football, tennis, hockey, and wrestling.

- Micro-traumas, carrying a bulky rucksack (N. Accessories), or repeatedly straining the neck in later flexion as in tennis (N. Thoracicus longus). There have also been reports of occupational injuries among auto mechanics, naval personnel, scaffolders, welders, carpenters, labourers, and seamstresses.

Following an infection:

- Poliomyelitis, tonsillitis-bronchitis, influenza infection, etc.

Iatrogenic Injury:

- Due to difficulties following surgery, such as the insertion of a chest tube [9], Because the long thoracic nerve is located close to the axillae, axillary lymph node excision during mastectomies for breast cancer carries an increased risk. Spinal accessory nerve damage from neck dissection may result in trapezius paralysis.

- Drug overdoses, allergic responses to drugs, and exposure to toxins (herbicides and tetanus antitoxin)

- Chiropractic Manipulation’s Effects

- Utilising a Solitary Axillary Crutch

Congenital:

- Fascioscapulohumeral Dystrophy in Muscular Dystrophy

Spontaneous:

- As with Parsonage-Turner syndrome, it is idiopathic.

Clinical presentation of winging of the scapula:

Pain: Neuritis or a neurological trauma are the major causes of acute or agonising pain that frequently keeps people awake. However, winged scapula resulting from muscular causes are not uncomfortable; however, some people may feel some discomfort. Overcompensating periscapular muscles can strain and spasm, resulting in pain that might feel heavy and dull-aching.

Having trouble lifting objects and raising the arm over the head. Individuals were unable to stretch their shoulders over 120°.

Weariness was a noteworthy feature.

On the physical exam:

In patients with serratus anterior palsy, the protrusion of the medial section of the scapula, which is not anchored against the rib cage, causes deformation of the back. This deformity should be recognised by medical professionals.

- Trapezius palsy: Asymmetrical neckline and sagging of the affected shoulder are signs of trapezius palsy. The scapula may wing and move laterally in conjunction with this.

- Rhomboids palsy: It results in a very little winging of the scapula, rotating the inferior angle laterally, and translating the scapula laterally.

Providers can evaluate patients using the following clinical tests:

For patients with serratus anterior palsy, position them such that their afflicted arm is out in front of them and parallel to the floor, with their back to a wall. The next step should be to tell the patient to press their afflicted side against the wall using the palm of their hand. Then, a protrusion of the medial region of the scapula indicating serratus anterior palsy should be visible.

- Trapezius palsy: Winging is usually insignificant and is therefore easily overlooked. The scapula moves upward during arm abduction, emphasising the superior angle’s greater lateral proximity to the midline than the inferior angle. When the arm is bent forward, the serratus anterior muscle acts, causing winging to vanish.

- Rhomboidal palsy: When a patient extends their arm from a completely flexed posture, the inferior angle of their scapula is dragged off the thoracic wall dorsally and laterally, causing winging. One way to assess a patient’s weakness in the rhomboids is to have them attempt to medially pull their scapulae together or push their elbows back against resistance while placing their hands on their hips. Either task’s difficulty points to the rhomboids’ fragility; however, trapezius hypertrophy may be hiding this.

| Medial winging | Lateral winging | ||

| Affected nerve | Long thoracic nerve | Spinal accessory nerve | Dorsal scapular nerve |

| Muscle palsy | Serratus anterior | Trapezius | Rhomboids |

| Physical examination | Bending of the arms and pushing up against a wall | Abduction of the arms; external rotation against opposition | Extension of the arm from complete flexion |

| Position of the scapula | Entire scapula displaced more medial & upwards | Superior angle more outward displaced | Inferior angle more outward displaced |

Diagnostic Procedures:

- After doing a comprehensive history and physical examination, a practitioner can make the diagnosis of scapular winging.

- To identify the underlying neuromuscular disease, electrodiagnostic tests might be helpful.

- Establishing muscular disease and its neurologic origins can be done with neuromuscular ultrasonography.

Differential Diagnosis:

- Rotator Cuff Disorders

- Frozen Shoulder

- Over-stressed Trapezius

- Glenohumeral Instability

- Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

- Cervical Spondylosis

- Acromioclavicular Disorder

Management of the winging of the scapula:

Currently, there is no suggested treatment plan for the first stages of scapular winging. Pain management and physical therapy are the suggested first treatments, as previously described. Patients who do not receive therapy at an early stage of the illness may develop frozen shoulder, adhesive capsulitis, subacromial impingement, and other brachial plexus-related pathologies.

Medical management of the winging of the scapula

There are surgical treatments when the patient is really satisfied with the results. However, other research favours non-operative care, particularly for elderly individuals who have few symptoms and are inactive.

These medical procedures are:

- Split Pectoralis Major Transfer

- Modified version of the Eden-Lange Procedure

- Scapuloplexy

Physical Therapy Management of Winging of Scapula

The cause of the scapular winging determines the course of physiotherapy.

Serratus anterior palsy:

- Patients should be encouraged to avoid painful activities and to avoid using the affected extremity overhead after receiving a diagnosis.

- It is also advisable to prescribe range of motion (ROM) exercises in the supine position. The weight of the body in the supine posture compresses the scapula against the thorax, preventing winging and permitting complete range of motion in the shoulders.

- It is especially important to avoid straining the serratus anterior muscle, since doing so can shorten the period of time it takes for functional recovery as well as the degree of recovery.

- A scapular brace has been demonstrated to be a generally useful treatment option for cooperative patients. It can accomplish the dual goals of maintaining the scapula positioned against the thorax and preventing the serratus anterior muscle from being stretched. Unfortunately, there is often poor brace tolerance, which results in low compliance and a reduced amount of functional recovery.

- There are three phases of long thoracic nerve damage, and Watson and Schenkman have recognised them, along with the proper care for each.

- Pain relief and range-of-motion exercises are the main objectives of therapy for acute-stage denervation of the serratus anterior. Reducing the patient’s activities is also crucial to preventing more shoulder damage.

- The nerve is starting to mend at the middle stage, when the pain has decreased. Passive stretching of the levator scapulae, pectoralis minor, and rhomboids is utilised to preserve complete range of motion and avoid rigidity of these muscles resulting from a decrease in serratus anterior activity.

- The shoulder mechanics improve as the serratus anterior is increasingly stronger in the third, or late, stage. Avoiding overstretching the serratus anterior and engaging in strengthening exercises for all shoulder girdle muscles, including the trapezius, can help you get stronger and perform better overhead.

Trapezius Palsy:

- Conservative measures including physical therapy, transcutaneous nerve stimulation, external assistance, chiropractic adjustments, NSAIDS, and narcotic analgesics may not always help with functional rehabilitation of the trapezius muscle resulting from spinal accessory nerve damage.

- For patients with paralysis of the trapezius muscle, a shoulder orthosis has been designed and has been utilised with some degree of effectiveness following radical neck dissection. After utilising the orthosis for three months, 72% of patients reported being pain-free, having better shoulder girdle muscle function, and having more endurance and function since they were no longer in discomfort. Active abduction, however, only made a 5–20° improvement.

- The Eden-Lange muscle transfer technique is the recommended course of treatment for those with isolated chronic trapezius palsy resulting from spinal accessory nerve damage who are in good condition and are physically active.

Rhomboids Palsy:

- Conservative treatment for injuries to the rhomboid muscles or dorsal scapular nerve often consists of physical therapy, muscle relaxants, anti-inflammatory medications, and cervical spine stabilisation (collar or cervical traction).

- The main goal of physical treatment is to strengthen the trapezius since the middle part of the trapezius can compensate for paralysis or rhomboid weakness.

Revalidation Programme:

We must pay close attention to a variety of monitoring metrics throughout the revalidation. In the revalidation programme, timing, muscle activity, muscular balance, endurance, and scapular muscle strength are crucial.

- Scapular muscles are activated consciously.

- Correct the patient’s scapular posture by asking them to shift it inside and downward while providing tactile input at the level of the angulus inferior.

- Feedback on muscle control from the scapulothoracic region at the sternum level

- The patient placed his fingers on the process coracoideus and then used those same fingers to shift his scapula backwards (medio-cranial).

- Myofeedback

Automate control of the scapular muscles:

- Hand held on a 90° anteflexion while maintaining rhythmic stability in a lateral position

- Hand support on the ball against the wall and rhythmic stability in the stand

- External rotation of the shoulder, retraction of the shoulder girdle, and rhythmic stabilisation in the prone position

- Rhythmic stabilisation when prone, protraction of the shoulder girdle, and submaximal elevation of the arm

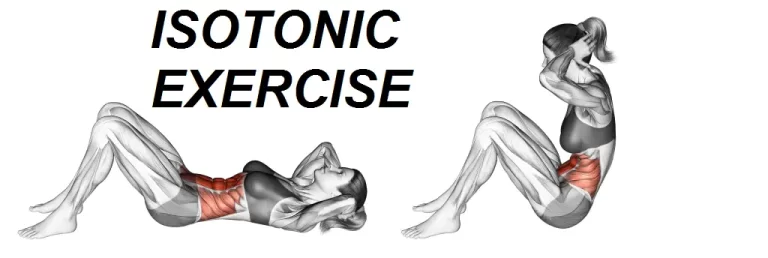

Dynamic training of the scapulothoracal muscles:

- A push-up is enhanced by more scapular protraction.

- elevation during exorotation in the scapular flat

- Elbow press-ups

- Hold up

- low-angle rowing

- Abduction horizontal

- Reflexion in opposition to opposition

- Straight, prone, and fitter serratus punch

- Exercise: Dynamic embrace with elbow in posterior pocket

Exercises for the Winged Scapula

Painless and mild are the goals of the wing-scapula exercises that follow.

Release the pec minor:

Instructions:

- Underneath your pec minor, place a massage ball.

- Search for your PEC minor on Google to find its location.

- Put your weight on the ball; that is the massage.

- Continue moving in a circle over the ball.

- Be sure to fully envelop the muscle.

- Time: one or two minutes

Stretches for a Winged Scapula:

- Levator Scapula

- Instructions:

- At the hip height, grasp a fixed item.

- (If you have a stretch or resistance band, you may also use it.)

- In order to lock the shoulder blade down, slant away from that hand.

- Turn your head to face the armpit on the other side.

- Using your other hand, pull the side of your head further to enhance the strain.

- Feel for a stretch between your shoulder blades and neck.

- For at least thirty seconds, hold.

- Do this three times.

- Pec Minor

- Instructions:

- Put your hands on a door frame at a certain height. (Refer to the above.)

- Bend the backs of your shoulder blades.

- Take a forward lunge.

- Try to experience a stretch in your chest.

- As you press against the wall, watch out that your lower back does not arch.

- Keep your ribs from protruding outward.

- For 30 seconds, hold.

- Do this three times.

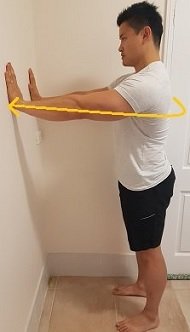

- Front shoulder stretch

- Instructions:

- Let your body descend as far as it will go while placing both hands on a seat behind you. (Refer to the above.)

- Keep the backs of your shoulder blades inclined.

- Keep your elbows close together.

- Prevent them from escalating.

- Keep your shoulders from hunching forward.

- In front of your shoulders, there should be a stretch.

- For 30 seconds, hold.

- Do this three times.

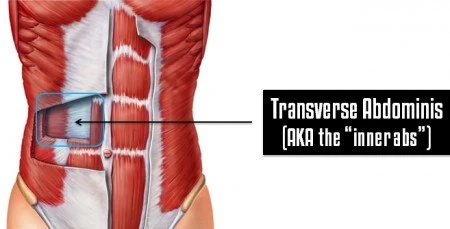

Activate the Serratus Anterior:

The serratus anterior’s primary job is to maintain your shoulder blade flat against your rib cage.

Understanding how to engage and sense the activation of the serratus anterior muscle is crucial while executing the winged scapula movements.

Exercise for Serratus Anterior:

Serratus anterior workout with winged scapula instructions:

- Assume the location of the wall plank.

- Get the Serratus Anterior in Motion:

- Raise your shoulders backward.

- Draw your shoulder blades around and down towards your ribcage.

- Maintain a broad, long-shoulder stance.

- Maintain a perfectly relaxed neck. (Avoid shrugging!)

- Firmly press your forearms against the wall.

- Try to feel the scapula’s side and bottom regions contracting.

- As you press your forearms against the wall, round your back if you are unable to feel the contraction.

- For 30 seconds, hold.

- Five times over, repeat.

Progression: Slide your forearms up and down the wall while keeping your serratus anterior activated.

Let’s begin the workouts for the serratus anterior after you know precisely how to engage this unique muscle.

There is a difficulty ranking for each workout. Try to wait until you’re ready to go on to the next level.

Level 1: Isolate the Serratus Anterior

- Rock back

- Instructions:

- Place your knees on the floor and adopt the plank posture.

- Make the serratus anterior active.

- Plant your forearms firmly on the ground.

- As far as you can, rock your body backwards.

- Throughout the exercise, make sure you can feel the serratus anterior contracting.

- Go back to where you were before.

- Do this thirty times.

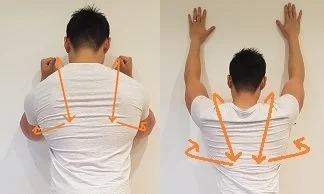

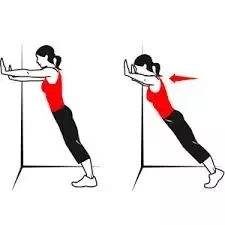

- Push-up plus (against the wall)

- Instructions:

- Lie down on the wall in the push-up posture, arms extended.

- Make the serratus anterior active.

- Grasp the wall with your hands.

- Continue to extend your shoulder blades while maintaining a straight arm position.

- Imagine your shoulder blades moving in a smooth, circular motion.

- For five seconds, hold this final position.

- Throughout the exercise, make sure you can feel the serratus anterior contracting.

- Return your shoulder blades to their initial, neutral posture slowly.

- Do this thirty times.

- Push-up plus (plank position)

- Instructions:

- Take a plank stance against the wall. (Refer to the above.)

- Make the serratus anterior active.

- Firmly press your forearms against the wall.

- Holding your forearms on the wall, extend your shoulder blades.

- Imagine your shoulder blades moving in a smooth, circular motion.

- For five seconds, hold this final position.

- Throughout the exercise, make sure you can feel the serratus anterior contracting.

- Return the shoulder blades to the neutral beginning posture.

- Do this thirty times.

Level 2: Serratus Anterior Exercises (+ Resistance)

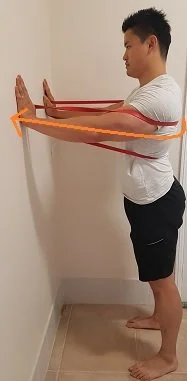

- Push-ups plus (with a band for resistance)

- Instructions:

- As seen above, hold onto a resistance band.

- (Ensure that the resistance you select is manageable.)

- With your arms extended, take a stance like the one above against the wall.

- Make the serratus anterior active.

- Continue to extend your shoulder blades while maintaining a straight arm position.

- For five seconds, hold this final position.

- Throughout the exercise, make sure you can feel the serratus anterior contracting.

- Return the shoulder blades to the neutral beginning posture.

- Do this thirty times.

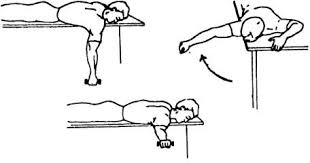

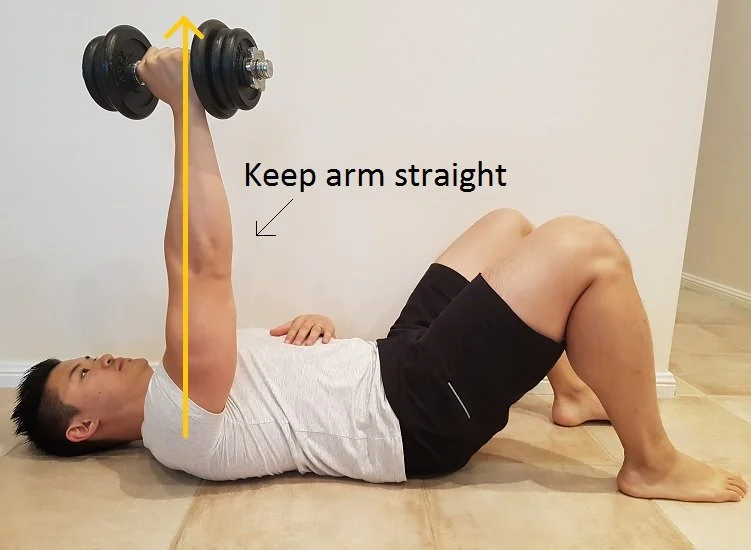

- Protraction in lying

- Instructions:

- Flex your knees & lie on your back.

- Keeping your hands on a weight, extend your arms straight ahead of you.

- Select a weight that you can hold well.

- Make the serratus anterior active.

- Keep the arm perfectly straight and push the weight up towards the sky.

- Hold on for five seconds.

- Throughout the exercise, make sure you can feel the serratus anterior contracting.

- Go back to where you were before.

- Do this thirty times.

- Progression: Roll your body to the side while maintaining the arm’s vertical posture, as demonstrated above. Do this fifteen times.

Level 3: Shoulder Movement and Serratus Anterior Activation

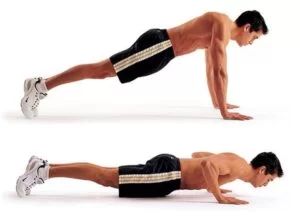

- Push up

- Instructions:

- Take a push-up stance against the wall.

- Engage the serratus anterior during the entire motion.

- Do a push-up.

- Maintain a broad, long shoulder stance.

- Do this thirty times.

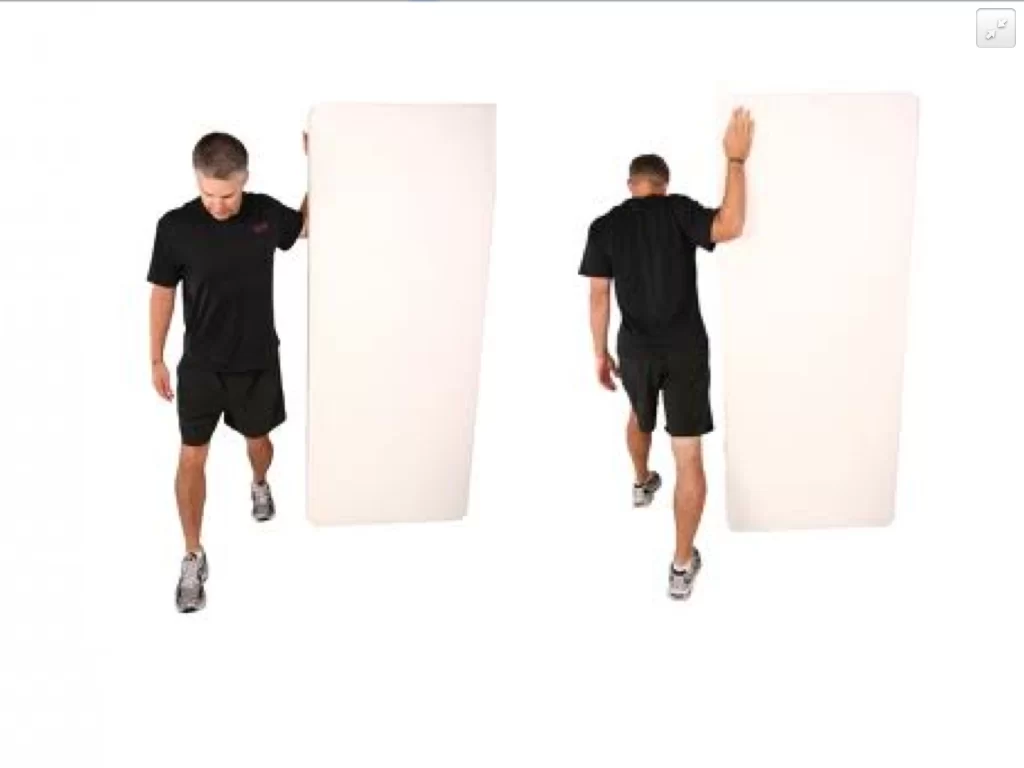

- Wall slides (with a band of resistance)

- Instructions:

- Grasp a resistance band firmly. (Refer to the above.)

- Select a resistance that feels correct for you.

- Assume the location of the wall plank.

- Engage the serratus anterior during the whole range of motion.

- Move your wrists from side to side along the wall.

- Continue applying pressure with your forearms to the wall.

- Do this fifteen times.

- One arm pivot

- Instructions:

- Assume the location of the wall plank.

- Pull the muscle in your serratus anterior.

- Press the forearm against the wall, located on the side of the winged scapula.

- Keep up this pressure the whole workout.

- Spin your body away, but don’t take your arm off the wall.

- Go back to where you were before.

- Do this fifteen times.

- Arm raises (with resistance band)

- Instructions:

- Grasp a resistance band firmly. (as previously indicated)

- Engage the serratus anterior during the whole range of motion.

- As you raise your hand, try to push it as far away from your body as possible while maintaining a back, down, and rotating posture for your shoulder blades.

- Drive your both arms up & down by your sides.

- Do this fifteen times.

Level 4: Carry Your Weight in Both Arms

- Plank

- Instructions:

- On the floor, take on the plank stance. (Refer to the above.)

- Pull the muscle in your serratus anterior.

- Plant your forearms firmly on the ground.

- For thirty seconds, maintain this posture.

- Keep your shoulder blades from sagging.

- Note: You can perform this exercise on your knees if you are unable to keep your shoulder blade in a proper posture.

- Push up

- Instructions:

- On the floor, take a push-up position. (Refer to the above.)

- Throughout the entire movement, contract the serratus anterior muscle.

- Do a push-up.

- Keep your shoulder blades from sagging.

- Maintain a long, broad shoulder!

- Ten times over, repeat.

Level 5: One-Armed Weight Bearing

- Straight arm plank (with pivot)

- Instructions:

- Assume a plank stance with your arms straight.

- Throughout the workout, keep your serratus anterior muscles engaged.

- Swing your weight into the hand on the winging side of your scapula.

- Slowly move your body aside while keeping that arm fixed on the ground. (Refer to the above.)

- Go back to where you were before.

- Ten times over, repeat.

- Advancement: Proceed more slowly.

- Plank (with pivot)

- On the floor, take on the plank stance.

- Pull the muscle in your serratus anterior.

- Press the targeted side of the forearm against the ground.

- Keep up this pressure the whole workout.

- Elevate your other forearm off the ground and rotate your body away.

- Go back to where you were before.

- Do this fifteen times.

Avoid these exercises when handling the winged scapula

Squeeze your both shoulder blade back together isn’t a useful method.

(In fact, this motion can exacerbate your scapular winging!)

Instead, get knowledgeable about proper shoulder blade positioning.

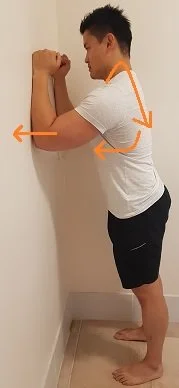

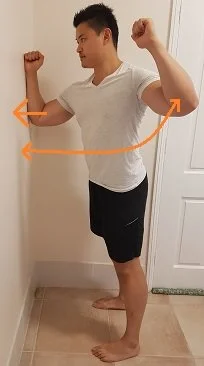

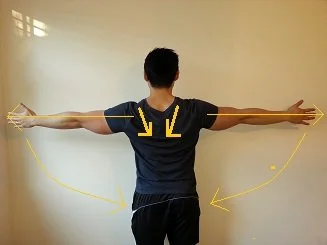

How Shoulders Should Be Positioned

Instructions:

- Activation of the serratus anterior:

- As far as you can, extend your hands to the opposing sides. (Refer to the above.)

- Maintain a broad, long shoulder stance.

- Retraction:

- Raise your arms to a little back position.

- Try to feel your shoulder blades contract slightly.

- (Avoid excessively compressing your shoulders back together.)

- Reverse Tilt:

- As much as you can, turn your arms backwards until your thumbs are nearly pointing at the ground.

- The last action is to note your shoulder posture.

- Maintain this stance while lowering your arms gently to your sides.

Additional Topics to Cover

Should you have persevered with these winged scapula exercises and are still having problems with the scapula position, you might also need to work on the rib cage’s posture.

The following have an impact on this:

a) Scoliosis

- scapula with winged scoliosis

- The term “scoliosis” describes the lateral curvature of the lumbar or thoracic spine.

- This may have an impact on the rib cage’s form, which supports the scapula.

b) Flat Thoracic Spine

- The posterior region of the rib cage may also seem flat if the thoracic spine is flat (lack of the normal kyphotic curvature).

- This will have an impact on how the rib cage and shoulder blade rest.

FAQ

What muscles strengthen scapular winging?

Avoiding overstretching the serratus anterior and engaging in strengthening exercises for all shoulder girdle muscles, including the trapezius, can help you get stronger and perform better overhead.

Can physiotherapy fix the winged scapula?

Using physical therapy to manage symptoms can be helpful. A physiotherapist creates a customised treatment plan that includes conditioning, strengthening, and/or stretching exercises to help you heal. regaining mobility.

Do push-ups help winged scapulas?

A useful exercise for strengthening the serratus anterior muscles is a shoulder push-up. The goal is to move your shoulders, not your elbows, to push your chest away and towards the earth.

Can winged scapulas go away?

The majority of patients with scapular winging who receive therapy as soon as possible recover completely. Patients frequently learn to use the trapezius muscle to compensate for their serratus anterior palsy. Recovery with conservative treatment might take several months or even years.

Can you permanently fix the winged scapula?

The preferred course of therapy for flying scapulas is surgery, since it permanently attaches the scapula to the rib cage.

What are the two types of scapular winging?

Depending on the direction of winging, there are two types of scapula winging: lateral and medial. More often, medial winging results from paralysis of the serratus anterior.

What muscle is weak with scapular winging?

Scapula winging occurs rarely. Winging may result from damage to the muscles themselves, a malfunction in the muscles’ supply system, or both.

What should I avoid with a winged scapula?

You may lessen your symptoms and avoid the crippling effects of scapular winging by making lifestyle changes. You should refrain from doing strenuous weightlifting and prolonged, repeated exercises like swimming, digging, and reaching up above objects.

How do you sleep with a winged scapula?

Sleep on your back instead, since this maintains a stable and proper alignment of your shoulders. Try sleeping on your side, the side opposite your sore shoulder, if lying on your back isn’t comfortable for you.

Can you live with a winged scapula?

A rare but potentially crippling illness called scapular winging can make it difficult to push, pull, and lift large things and to carry out regular tasks like carrying grocery bags and cleaning one’s teeth.

Reference

- “Scapular Winging.” Physiopedia, www.physio-pedia.com/Scapular_Winging. Accessed 19 Dec. 2023.

- Mark. “Winged Scapula Exercises.” Posture Direct, 11 Oct. 2023, www.posturedirect.com/how-to-fix-a-winged-scapula.