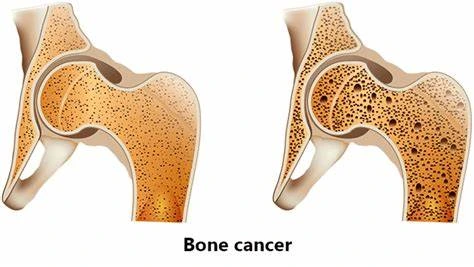

Bone Cancer

Introduction

Bone cancer is a rare and serious disease that forms in bones. It occurs when normal cells in the bone transform into abnormal cancer cells that multiply uncontrollably. Primary bone cancer means the cancer starts in the bones, while secondary bone cancer means the cancer spreads to the bones from elsewhere in the body.

There are several different types of primary bone cancer, with osteosarcoma being the most common. Bone cancer can develop at any age, but is most prevalent in children, teens, and young adults.

Detecting bone cancer early on greatly improves one’s prognosis and survival chances. Many of the warning signs, like bone pain or swelling, can also indicate more common, non-cancerous conditions. However, the patient must reach out to their healthcare provider if they experience symptoms that persist. A timely diagnosis allows for prompt treatment when the cancer may be more effectively managed.

Diagnosing bone cancer can be complicated as the patient often presents common symptoms that mimic other bone conditions. There is no definitive diagnostic test, so physicians utilize X-rays, bone scans, CT scans, MRI scans, and biopsies to confirm. Treatment typically involves some combination of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation which poses both difficulties and side effects. Survival outcomes vary greatly depending on the type and stage of bone cancer upon diagnosis. Advances are still needed to improve early detection methods and to develop targeted cancer therapies.

Types of Bone Cancer

Primary bone cancer

Osteosarcoma

Osteosarcoma is the most common type of bone cancer and predominantly impacts children and young adults. It originates from bone-forming cells and most often occurs in the long bones of the arms and legs. Symptoms include bone pain and swelling. It can spread to other tissues like lung. Treatment options range from surgery, chemotherapy drugs, to sometimes radiation.

Chondrosarcoma

Chondrosarcoma starts in cartilage cells and represents about 20% of primary bone cancers. It is more common among adults over 40 years old. Slow-growing tumors occur in the pelvis, leg, and arm bones causing pain and limitation in movement. Higher-grade tumors can spread to the lungs and lymph nodes. Surgical removal is the main treatment.

Ewing Sarcoma

Ewing sarcoma is the second most prevalent primary bone cancer in children and young adults. It forms in the bone and soft tissue around the bones. Symptoms involve bone pain, swelling, and sometimes fever. Tumors arise in the legs, pelvis, ribs, and arms. Chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery are typical treatment approaches, often in combination.

Chordoma

Chordomas develop along the spine, often in the base of the skull and tailbone. Signs include pain, neurological issues, and sometimes bleeding. The malignant, slow-growing tumors affect adults ages 50-60, metastasizing rarely but locally invasive. Treatment entails high-dose radiation with extensive surgery. The overall prognosis is poor due to the difficulty of fully removing the tumor.

Fibrosarcoma

Fibrosarcoma originates in the soft fibrous tissue of the bones. Most occur in the legs and arms of adults 30-55 years old. Symptoms are pain and swelling. It can regrow post-treatment but rarely spreads beyond the original site. Radical surgical removal with radiation and chemotherapy drugs serves as the primary treatment approach.

Adamantinoma

A rare primary tumor occurring almost exclusively in the leg and arm bones of adults ages 30-50. Adamantinoma appears similar to osteosarcoma on X-rays but grows slower. Options range from limb salvage orthopedic surgery to amputation. The advanced disease carries a poor prognosis due to metastasis into the surrounding tissue.

Secondary bone cancer

Metastatic bone cancer

- Cancer that starts elsewhere and spreads to the bone which are common than primary bone cancer.

- Most originate from breast, prostate, lung, thyroid, or kidney cancer spreading to bone.

- Symptoms like pain or fractures. The spread is diffuse. 5-year survival varies by primary cancer type.

Causes and risk factors

- metastasis to bone often related to primary cancer type (breast, lung, etc.)

- Risk increased by the advanced stage of the primary tumor, high-grade cell classification

- Cancer treatments like radiation or hormones can very rarely cause a new secondary cancer

Rare types of bone cancer

Giant cell tumor of bone

- Noncancerous but can be aggressive tumor occurring in ends of long bones

- Typically affects young adults between the ages of 20 and 40 years old

- Most common in the knee, followed by shoulder and wrist joints

- Symptoms include pain, swelling, decreased joint movement, fractures

- Appears on X-rays as the light area with a “blown-out” bony appearance

- Initially benign but can transform over time into high-grade malignant tumors

- Treatments focus on surgical curettage (scraping) with bone grafting or joint replacement

- Can recur locally in 10-20% of cases post-surgery so close monitoring needed

- In a small % metastasizes to the lungs despite benign pathology

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma

- A rare cancerous tumor that arises from soft tissue & fibrous connective tissue

- Occurs most often in arms, legs, or retroperitoneum (abdomen/pelvis)

- Most common bone cancer in late adulthood (over age 55), peak age 60-80+

- Presents with growing mass, pain, fractures

- High risk for metastasis to lungs and lymph nodes

- Treated aggressively with limb-sparing surgery or amputation plus chemotherapy

- 5-year survival varies from 18% (metastatic high grade) up to 88% (localized low grade)

Eosinophilic granuloma

- Not malignant – localized tumorous growth that resolves eventually

- Part of Langerhans cell histiocytosis, more common in children and teens

- Manifests as single or multiple growths in skull, spine, pelvis, ribs

- Symptoms are bone pain, fractures, tenderness over affected areas

- Supportive care, low-dose chemo, or radiation in some advanced cases

- Often no treatment is needed as lesions often resolve spontaneously over months to years

Symptoms

The following are the most typical signs of bone cancer:

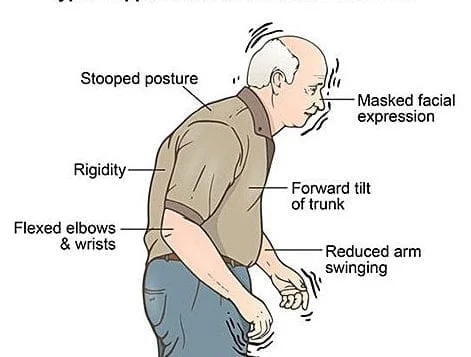

- Bone pain – Typically the first noticeable symptom. Persistent aching pain that increases over time. Worsens at night or with activity. Not relieved with pain medications.

- Swelling – Enlargement over the affected bone area as the tumor grows. Visible or palpable mass.

- Fractures – Bones weakened by tumors are susceptible to breaks with minor trauma that would otherwise not cause a fracture.

- Reduced joint motion – Tumors around joints lead to stiffness, limited range of motion, or joint malfunction.

- Nerve issues – Growth and spread of tumors into nearby nerves cause numbness, tingling, or muscle weakness. Most common with spinal tumors pressing on the spinal cord.

- Unintended weight loss – Some forms are metabolically active, leading to elevations in metabolism and increased weight loss. Signs of wasting indicative of metabolically demanding disease or cancer cachexia compounded by poor appetite.

Diagnosis

No single diagnostic test definitively diagnoses bone cancer. Since symptoms overlap with other benign bone conditions, physicians rely on a combination of imaging tests, blood work, and biopsies to confirm the presence and type of bone cancer. Steps include:

- Medical history – Discuss onset/timing, location, and quality of symptoms

- Physical examination – Assess areas of pain or abnormal growths

- Imaging tests – X-rays, CT scans, PET scans, MRI scans, bone scans to visualize tumors

- Blood tests – Evaluate blood cell counts, organ function, specific blood tumor markers

- Biopsy – Removal of a tissue sample by needle or surgery examined by a specialist for signs of cancer

- Staging – Determining the size, grade, and metastasis of the tumor

The diagnosis process aims to confirm the presence of bone cancer, identify specific types, and assign accurate stages to guide an appropriate treatment plan.

Staging Bone Cancer

TNM System

The stage of bone cancer is assigned using the TNM system from the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC). This considers:

T – Size and local extent of primary tumor

T0 – No evidence of tumor

T1, T2, T3, T4 – Increasing size and/or extent of the original tumor

N – Degree of spread to nearby lymph nodes

N0 – No cancer detected

N1 – Cancer spread to nearby lymph nodes

M – Presence of distant metastasis

M0 – No distant metastasis

M1 – Distant metastasis detected

Overall Stage Grouping:

Stage 1 – Low-grade, small, localized tumor (T1 N0 M0)

Stage 2 – Higher grade, larger tumor without metastasis (T2/3 N0 M0)

Stage 3 – Tumor of any size with lymph node spread (T1-3 N1 M0)

Stage 4 – Distant metastases present (Any T, Any N, M1)

Determining Metastasis and Extent of Cancer

Healthcare providers determine if bone cancer has metastasized using:

- Blood tests checking for elevated tumor markers associated with metastasis

- PET scan tracing metabolic signals through the whole body

- CT scan of chest checking lungs most common site

- Bone scan inspecting for areas of bone remodeling as a sign of spread

- MRI examining bone marrow infiltration by cancer cells

The stage of cancer guides prognosis and is a key factor directing bone cancer treatment approach. Accuracy is critical, so an oncologist specializing in bone tumors often oversees precise staging.

Treatment Approaches

Surgical interventions

Surgery is a critical component of bone cancer treatment even when multi-modal approaches across chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery are utilized. Goals of surgery are to remove tumor tissue fully while preserving as much limb function as feasible.

Limb-sparing surgery

The standard surgery for most bone cancers is limb-sparing or limb-salvage surgery. This removes the tumor while saving most of the limb by rebuilding the bone. Techniques involve:

- Wide local excision: Removing cancerous bone and a margin of healthy tissue, muscle, and vessels surrounding it.

- Endoprostheses: Implanting an internal artificial joint or long bone replacement construct commonly using metals and plastics to restore structure and mobility.

- Allografts/autografts: Using donations of the patient’s bone, cartilage, or soft tissues for transfers or grafting.

- Compartmental resection: Removing some bone compartments but preserving major nerves, vessels, and muscles attached.

Amputation

- Required if the tumor cannot be fully excised or limb/joint function cannot be preserved

- Most common in pelvic tumors where location/extent prevents limb-sparing

- Also sometimes needed in recurrent tumors or aggressive sarcomas despite other surgeries

- Rotational hinge joints now allow prosthetic limbs to bend/rotate for improved function

- Phantom limb pain common long-term side effect needing pain management

- Rehabilitation focuses on strength, balancing, coordinating movement with prosthesis

Bone reconstruction

- Restoring bone integrity after segment removal essential for mobility

- Allografts use donated bone tissue usually sourced from bone banks or cadavers

- Typically femur or tibia segments are used to span gaps after surgical resection

- Graft incorporation depends on revascularization, cell migration into the matrix

- Autografts utilize the patient’s tissue like vascularized fibula transfer

- Endoprosthesis implant uses metals and plastics to replace joint/bone sections

- Allows early weight bearing but higher risk of complications like infection, loosening

Radiation Therapy

Radiation uses high-energy particles or waves to destroy cancer cells. It aims to shrink tumors or slow growth when surgery cannot remove them entirely or halt spread post-operatively.

External beam radiation

Most common delivery directs radiation to the site externally:

- The patient lies still on a table while the linear accelerator rotates aiming beams from outside the body into the tumor

- CT/MRI scans map the treatment field perfectly targeting tumor

- Typical regimens deliver radiation 5 days a week over 3-6 weeks

- Newer conformal techniques like IMRT/IGRT improve accuracy sparing healthy tissue

Brachytherapy

This internal radiation inserts radioactive material directly into or next to the tumor:

- Done during surgery after bulk tumor mass removed

- Radioactive rods, pellets, wires, or seeds implanted into the cancer site

- Positioned carefully using templates and scans to map inside anatomy

- High doses target residual tumor cells while sparing normal tissue

- Materials like iodine-125 or cesium-131 emit rays short distances over weeks/months

Side effects and precautions

- Fatigue compounding surgery/chemo demands

- Skin redness, irritation, and breakdown with external methods

- Low blood counts raise infection risk

- Nausea, vomiting, pain needing management

- Long-term bone weakening or second malignancy small risk

Ongoing physics advances aim to improve the effectiveness of hitting tumors while protecting adjoining organs/tissues.

Chemotherapy and Targeted Therapy

Drugs used in bone cancer treatment

- Doxorubicin – Anthracycline interfering with DNA replication

- Cisplatin – Binds to DNA strands inducing cell cycle arrest

- Methotrexate – Antimetabolite that inhibits folate-dependent enzymes disrupting cell growth

- Etoposide – Plant-derived compound causing DNA and cell division disruption

- Ifosfamide – Alkylating agent leading to cross-linking DNA damage

- Cyclophosphamide – Similar DNA effects as ifosfamide

- Targeted biologics like mTOR or VEGF inhibitors under study

Multidrug regimens and combination therapies

Chemotherapeutics are often given cyclically in varied combinations including:

- High dose MAP – Methotrexate, doxorubicin, cisplatin

- VAC/VIC – Vincristine, dactinomycin alternating with ifosfamide and etoposide

- mTOR inhibitors with MAP to target specific molecular pathways

Concurrent chemo and radiation maximize cell destruction. Pre-, post, and intraoperative (heated) chemo approaches were utilized too.

Potential benefits and side effects

In addition to tumor cell cytotoxicity, risks like infection, bleeding, fatigue, neuropathy, organ damage, nausea, appetite loss, hair loss, and fertility issues often occur requiring extensive supportive care. Skillful management can temper side effects enabling patients to complete planned regimens. Targeted biologics may offer future promise improving tumor specificity and tolerability.

Supportive Care and Rehabilitation

Managing Pain and Discomfort

Pain Management Techniques

- Controlling cancer-related pain is critical for quality of life and functional capacity. A multifaceted approach addresses diverse pain sources through:

- Pharmacologics – Medications like opioids, NSAIDs, nerve pain agents, and corticosteroids administered via routes from oral to intravenous target sensory signaling reducing centralized pain perception and peripheral sensitization. However, side effects warrant consideration.

- Interventions – Regional anesthetic nerve blocks, neurolytic ablations, intrathecal pumps infusing analgesics directly to the spinal fluid, or off-label centrally acting agents aim for pain relief while minimizing systemic effects.

- Physical modalities – TENS units stimulating nerves electrically, therapeutic ultrasound, and heat/cold therapies relieve musculoskeletal manifestations. Massage and acupuncture prove complementary.

- Psychological approaches – Relaxation training to reduce tension, and stress exacerbating pain. Distraction techniques and visualization take attention from discomfort. Emotional support regarding fears, anxiety, and depression influencing suffering.

- Holistic – Nutritional optimization through diet quality, micronutrients, and anti-inflammatory components enhances neurological health and resilience. Exercise increases circulation and endorphin production.

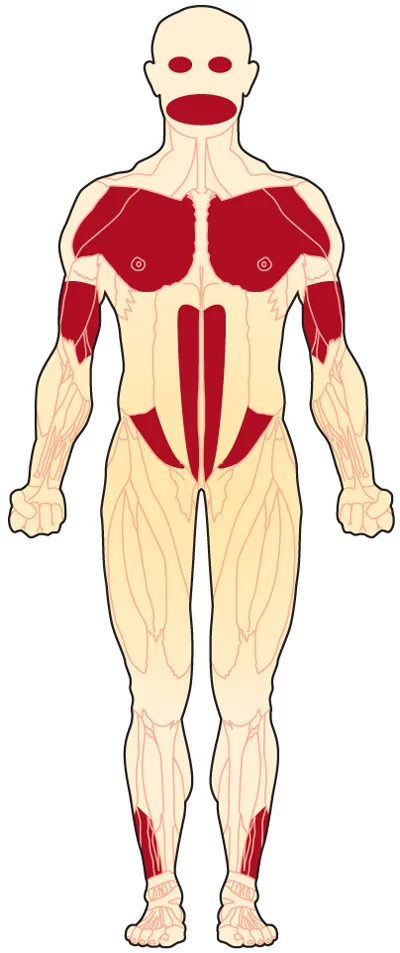

Rehabilitation Exercises

Supervised therapeutic exercises progress endurance, mobility, strength, and functionality compromised by tumor effects.

- Passive range of motion – The therapist manipulated movements to improve joint mobility after immobilization.

- Active range of motion – Patient initiated motions to regain muscular strength and coordination through increasing repetition.

- Resistance training – Added weights or resistance bands gradually build muscle tone as movement is tolerated.

- Weight-bearing activities – Compressive axial loads help maintain bone density.

- Balancing maneuvers – Standing and walking exercises retrain equilibrium reactions improving safety.

Emotional and psychological support

Coping with the diagnosis

- Adjustment counseling

- Psychoeducation on expected feelings

- Healthy outlet promotion

- Medical social work assistance

- Potential anti-anxiety or anti-depression medications

Support groups and counseling services

- Connections with fellow patients

- Shared experiences, advice

- Additional information source

- Individual or family therapy

- Identifying and processing emotions

Nutritional support and lifestyle adjustments

Diet recommendations for bone cancer patients

- High-calorie, high protein and nutrient-dense foods

- Liquid supplements if appetite is poor or swallowing difficulties

- Anti-nausea regimen

- Bone health promotion through calcium, Vitamin D

- Avoidance of alcohol, smoking

Exercise and physical activity

- Aerobic activity promotes strength, cardiovascular health

- Resistance training maintains muscle mass

- Balance and flexibility reduce injury risk

- The importance of rest days and listening to body limits

Prevention and Outlook

Prevention strategies for bone cancer

As most causes of primary bone cancer remain unknown, evidence-based prevention guidelines are limited. However, some potentially protective lifestyle measures may promote general wellness:

Lifestyle modifications

- Optimize nutrition through diets rich in whole foods high in antioxidants and phytochemicals to reduce cellular damage linked to DNA mutations and possible malignant transformations. Emphasize fruits, vegetables, and whole grains.

- Engage in regular weight-bearing physical activity for 30+ minutes daily to stimulate beneficial bone remodeling processes while reducing inflammatory mediators.

- Avoid or quit tobacco usage given the links between smoking and multiple cancer types. Discontinue alcohol which may also irritate tissues.

Regular medical checkups and screenings

- Since early detection proves critical, be vigilant for signs like unexplained bone pain or swelling and seek prompt workup. Those with histories of radiation or chemotherapy have slightly elevated second cancer risks warranting closer surveillance by physicians.

Prognosis and survival rates

Factors influencing prognosis

Primary bone cancer prognosis varies significantly by stage, histological grade, response to treatment, and metastatic disease status. Favorable indicators like small, low-grade, surgically accessible tumors boost 5-year survival. Meanwhile, prognosis declines with metastasis, incomplete excision, or radio/chemo-resistance.

Ongoing research and advancements

Improved risk stratification guides treatment aggressiveness and predicts outcomes more precisely. Advances in surgical techniques, radiation, immunotherapy drugs, and combinations thereof continue extending remission likelihood. Palliation therapies also progress prolonging survival with quality of life. Gene testing directs personalized medicine approaches matched to the molecular profile of patients’ cancer. Overall, bone cancer management continues progressing through dedicated research.

Summary

Bone cancer is a rare and serious disease where normal bone cells transform into abnormal cancerous cells. Primary bone cancer originates in the bone itself, while secondary bone cancers spread from other tumor sites. Osteosarcoma is the most common pediatric bone cancer. Symptoms involve bone pain, fractures, and swelling near the tumor site. Diagnosis relies on imaging tests like X-rays, CT, MRI, bone scans, and biopsies. Treatment is multi-disciplinary utilizing surgery, chemotherapy drugs, and radiation therapy.

Primary bone cancers include osteosarcoma of the arms, legs, and knees, cartilage tumors like chondrosarcoma, aggressive Ewing sarcoma tumors, chordomas of the spine, and rarer versions like adamantinoma. Secondaries arise from breast, lung, and other metastasized primaries. Benign but more aggressive tumors like giant cell tumors or malignant fibrous histiocytoma can also occur in bone.

Persistent bone aches worsened by movement, palpable mass, fracture from mild injury, joint issues and unintended weight loss are signals assessed in the patient history. Imaging modalities visualize abnormalities and guide needle biopsy by which a pathologist can determine cancer type. Blood assays provide complete cell counts and catch early metabolic indications of systemic effects.

Surgical options range from limb-sparing approaches using bone grafts or prosthetics for reconstruction to amputation in severe cases. Radiation delivered externally or internally attempts tumor shrinkage especially post-op. Chemotherapies like methotrexate combined with cisplatin, doxorubicin, and other cytotoxic cocktails target replicating cells systemically but have side effects warranting medication.

While often aggressive, localized low-grade versions have 60-80% 5-year survival rates. However, metastases or advanced disease at diagnosis confer under 30% 5-year outlooks. Continuing research improves characterization, personalized medicine, and novel therapies targeting mechanisms underlying each bone cancer subtype. Preventively, healthy lifestyle choices optimize wellness.

FAQs

What are the most common symptoms of bone cancer?

The most common symptoms are bone pain, swelling, fractures, reduced joint motion, nerve issues, and unintended weight loss. Pain is typically the first noticeable sign.

What tests diagnose bone cancer?

Doctors use imaging tests like X-rays, CT scans, PET scans, bone scans, and MRIs to visualize tumors. They also do blood tests and examine tissue samples from a biopsy to diagnose bone cancer.

What are the treatment options for bone cancer?

Common treatments incorporate some combination of surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, targeted drugs, clinical trials, and palliative care approaches to manage pain and symptoms.

What is the survival rate for bone cancer?

The 5-year survival rate ranges widely from 20% – 80% depending on the bone cancer type, stage at diagnosis, metastasis status, and responsiveness to treatments. Early localized tumors confer better odds.

Can you prevent getting bone cancer?

Prevention guidelines remain limited since causes are often unknown, but pursuing healthy lifestyles by optimizing diet, activity, and weight can aid general wellness as a protective measure.

Does bone cancer spread to other parts of the body?

Yes, cancers like Ewing’s sarcoma aggressively spread from bones to lungs, other bones, and tissue early on. Later-stage progression leads to diffuse metastatic disease lowering survival expectations.

Is bone cancer fatal?

While often very aggressive, bone cancer prognosis depends greatly on the specifics of each person’s diagnosis and response to coordinated specialty care. Between 20-80% survive at least 5 years, with the likelihood rising exponentially the earlier treatment can begin.

How is bone cancer treated in children vs adults?

Treatment principles of surgery and chemo radiation therapy remain the same, but pediatric regimens utilize growth plates to advantage, adapt doses by weight, and aim to avoid permanent damage to evolving structures.

References

Stuart, A. (2010, May 18). Bone Cancer. WebMD. https://www.webmd.com/cancer/bone-tumors

Welsh, J. (2023, June 19). What to Know About Bone Cancer. Verywell Health. https://www.verywellhealth.com/bone-cancer-7511400

Macon, B. L. (2022, February 16). Bone Cancer: Types, Causes, Symptoms, and More. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/bone-cancer#takeaway

Professional, C. C. M. (n.d.). Bone Cancer. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/17745-bone-cancer

Bone cancer – Symptoms and causes – Mayo Clinic. (2023, May 11). Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/bone-cancer/symptoms-causes/syc-20350217

https://th.bing.com/th/id/OIP.eOp34GWv2pxHztEBvMWBWgHaEL?rs=1&pid=ImgDetMain

2 Comments