Facial Nerve Palsy

What is a Facial Palsy?

Facial nerve palsy is a condition that causes weakness or paralysis of the facial muscles. The facial nerve is responsible for controlling muscle movement in the face, and its function is vital to everyday life.

Facial nerve palsy can be caused by a number of factors, including viral infections, trauma to the head or neck, or tumors. Treatment for this condition varies depending on its severity, but most cases allow for near-full recovery within six months.

The Facial nerve that controls the muscles of the face is damaged, resulting in weakness or paralysis of those muscles. Symptoms include facial droop, difficulty closing one eye, and difficulty eating or drinking.

Anatomy of Facial Nerve :

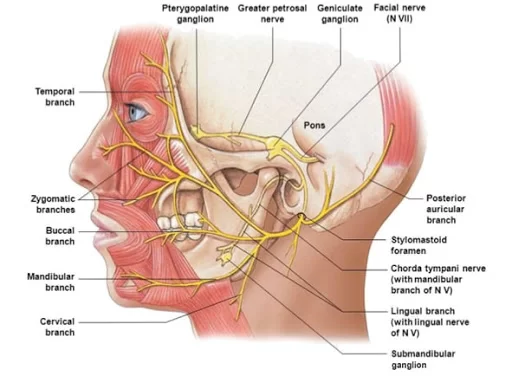

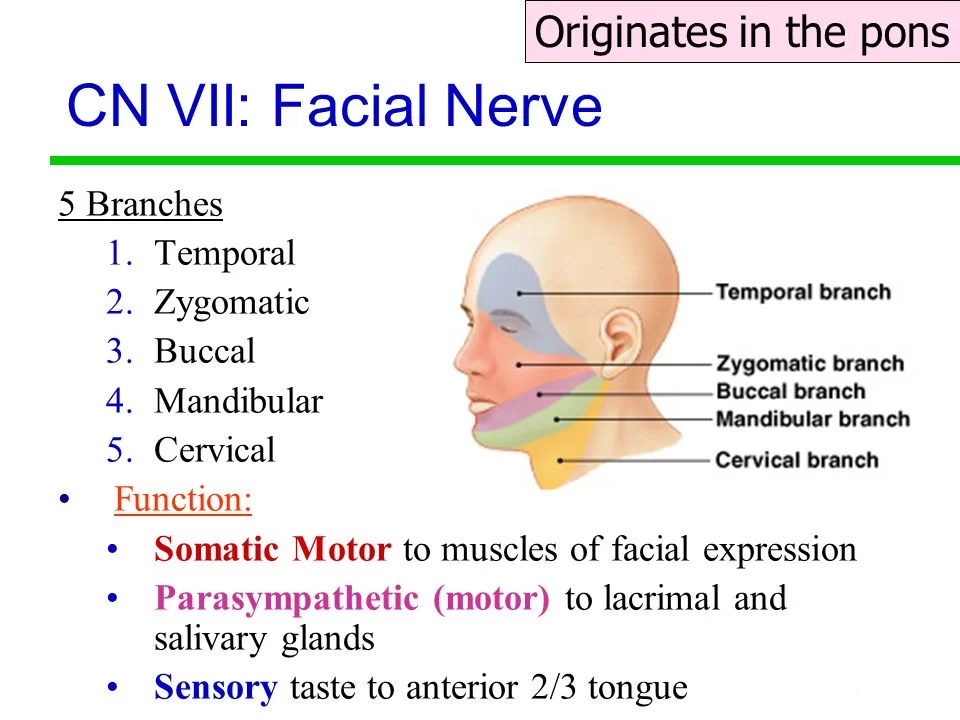

The facial nerve is the seventh cranial nerve, or simply cranial nerve VII. It emerges from the pons of the brainstem, controls the muscles of facial expression, and functions in the conveyance of taste sensations from the anterior two-thirds of the tongue. The nerves typically travel from the pons through the facial canal in the temporal bone and exit the skull at the stylomastoid foramen. It arises from the brainstem from an area posterior to the cranial nerve VI (abducens nerve) and anterior to the cranial nerve VIII (vestibulocochlear nerve).

The facial nerve also supplies preganglionic parasympathetic fibers to several head and neck ganglia.

The facial and intermediate nerves can be collectively referred to as the nervus intermediofacialis.

Structure of Facial Nerve

The path of the facial nerve can be divided into six segments.

1. Iintracranial (cisternal) segment

2. Meatal segment (brainstem to internal auditory canal)

3. Labyrinthine segment (internal auditory canal to geniculate ganglion)

4. Tympanic segment (from geniculate ganglion to pyramidal eminence)

5. Mastoid segment (from pyramidal eminence to stylomastoid foramen)

6. Extratemporal segment (from stylomastoid foramen to post parotid branches)

- The motor part of the facial nerve arises from the facial nerve nucleus in the pons while the sensory and parasympathetic parts of the facial nerve arise from the intermediate nerve.

2. From the brain stem, the motor and sensory parts of the facial nerve join together and traverse the posterior cranial fossa before entering the petrous temporal bone via the internal auditory meatus. Upon exiting the internal auditory meatus, the nerve then runs a tortuous course through the facial canal, which is divided into the labyrinthine, tympanic, and mastoid segments.

3. The labyrinthine segment is very short and ends where the facial nerve forms a bend known as the geniculum of the facial nerve (“genu” meaning knee), which contains the geniculate ganglion for sensory nerve bodies. The first branch of the facial nerve, the greater superficial petrosal nerve, arises here from the geniculate ganglion. The greater petrosal nerve runs through the pterygoid canal and synapses at the pterygopalatine ganglion. Post synaptic fibers of the greater petrosal nerve innervate the lacrimal gland.

4. In the tympanic segment, the facial nerve runs through the tympanic cavity, medial to the incus.

5 The pyramidal eminence is the second bend in the facial nerve, where the nerve runs downward as the mastoid segment. In the temporal part of the facial canal, the nerve gives rise to the stapedius and chorda tympani. The chorda tympani supplies taste fibers to the anterior two-thirds of the tongue and also synapses with the submandibular ganglion. Postsynaptic fibers from the submandibular ganglion supply the sublingual and submandibular glands.

6. Upon emerging from the stylomastoid foramen, the facial nerve gives rise to the posterior auricular branch. The facial nerve then passes through the parotid gland, which it does not innervate, to form the parotid plexus, which splits into five branches innervating the muscles of facial expression (temporal, zygomatic, buccal, marginal mandibular, cervical).

INTRACRANIAL BRANCH :

1. Greater petrosal nerve – It arises at the geniculate ganglion and provides parasympathetic innervation to several glands, including the nasal glands, the palatine glands, the lacrimal gland, and the pharyngeal gland. It also provides parasympathetic innervation to the sphenoid sinus, frontal sinus, maxillary sinus, ethmoid sinus and nasal cavity. This nerve also includes taste fibers for palate via lesser palatine nerve and greater palatine nerve.

2. Communicating branch to the otic ganglion – It arises at the geniculate ganglion and joins the lesser petrosal nerve to reach the otic ganglion.

3..Nerve to stapedius – provides motor innervation for stapedius muscle in middle ear

4. Chorda tympani

Parasympathetic innervation to submandibular gland

Parasympathetic innervation to sublingual gland

Special sensory taste fibers for the anterior 2/3 of the tongue.

EXTRACRANIAL BRANCHES

Distal to the stylomastoid foramen, the following nerves branch off the facial nerve:

Posterior auricular nerve – controls movements of some of the scalp muscles around the ear

Branch to the Posterior belly of Digastric muscle as well as the Stylohyoid muscle

Five major facial branches (in the parotid gland) – from top to bottom:

- Temporal branch

2. Zygomatic branch

3. Buccal branch

4.Marginal mandibular branch

5. Cervical branch

Intraoperatively the facial nerve is recognized at 3 constant landmarks:

- At the tip of tragal cartilage where the nerve is 1cm deep and inferior

2. At the posterior belly of digastric by tracing this back to the tympanic plate the nerve can be found between these two structures

3. By locating the posterior facial vein at the inferior aspect of the gland where the marginal branch would be seen crossing it.

4.lateral semicircular canal

5. Foot of incus

NUCLEUS

The cell bodies for the facial nerve are grouped in anatomical areas called nuclei or ganglia. The cell bodies for the afferent nerves are found in

the geniculate ganglion for taste sensation. The cell bodies for muscular efferent nerves are found in the facial motor nucleus whereas the cell

bodies for the parasympathetic efferent nerves are found in the superior salivatory nucleus.

DEVELOPMENT

The facial nerve is developmentally derived from the second pharyngeal arch or branchial arch. The second arch is called the hyoid arch because it contributes to the formation of the lesser horn and upper body of the hyoid bone (the rest of the hyoid is formed by the third arch). The facial nerve supplies motor and sensory innervation to the muscles formed by the second pharyngeal arch, including the muscles of facial expression, the posterior belly of the digastric, stylohyoid, and stapedius. The motor division of the facial nerve is derived from the basal plate of the embryonic pons, while the sensory division originates from the cranial neural crest.

Although the anterior two-thirds of the tongue are derived from the first pharyngeal arch, which gives rise to cranial nerve V, not all innervation of the tongue is supplied by CN V. The lingual branch of the mandibular division (V3) of CN V supplies non-taste sensation (pressure, heat, texture) from the anterior part of the tongue via general visceral afferent fibers. Nerve fibers for taste are supplied by the chorda tympani branch of cranial nerve VII via special visceral afferent fibers.

FUNCTIONS OF FACIAL NERVE :

Facial expression

The main function of the facial nerve is motor control of all of the muscles of facial expression. It also innervates the posterior belly of the digastric muscle, the stylohyoid muscle, and the stapedius muscle of the middle ear. All of these muscles are striated muscles of branchiomeric origin developing from the 2nd pharyngeal arch.

FACIAL SENSATION

In addition, the facial nerve receives taste sensations from the anterior two-thirds of the tongue via the chorda tympani. The taste sensation is sent to the gustatory portion (superior part) of the solitary nucleus. General sensations from the anterior two-thirds of the tongue are supplied by afferent fibers of the third division of the fifth cranial nerve (V-3). These sensory (V-3) and taste (VII) fibers travel together as the lingual nerve briefly before the chorda tympani leaves the lingual nerve to enter the tympanic cavity (middle ear) via the petrotympanic fissure.

It joins the rest of the facial nerve via the canaliculus for chorda tympani. The facial nerve then forms the geniculate ganglion, which contains the cell bodies of the taste fibers of chorda tympani and other taste and sensory pathways. From the geniculate ganglion, the taste fibers continue as the intermediate nerve which goes to the upper anterior quadrant of the fundus of the internal acoustic meatus along with the motor root of the facial nerve. The intermediate nerve reaches the posterior cranial fossa via the internal acoustic meatus before synapsing into the solitary nucleus.

The facial nerve also supplies a small amount of afferent innervation to the oropharynx below the palatine tonsil. There is also a small amount of cutaneous sensation carried by the nervus intermedius from the skin in and around the auricle (outer ear).

OTHERS-

The facial nerve also supplies parasympathetic fibers to the submandibular gland and sublingual glands via chorda tympani. Parasympathetic innervation serves to increase the flow of saliva from these glands. It also supplies parasympathetic innervation to the nasal mucosa and the lacrimal gland via the pterygopalatine ganglion. The parasympathetic fibers that travel in the facial nerve originate in the superior salivatory nucleus.

The facial nerve also functions as the efferent limb of the corneal reflex.

FUNCTIONAL COMPONENT-

The facial nerve carries axons of type GSA, general somatic afferent, to the skin of the posterior ear.

The facial nerve also carries axons of type GVE, general visceral efferent, which innervate the sublingual, submandibular, and lacrimal glands, also the mucosa of the nasal cavity.

Axons of type SVE, special visceral efferent, innervate muscles of facial expression, stapedius, the posterior belly of digastric, and the stylohyoid.

The axons of type SVA, special visceral afferent, provide taste to the anterior two-thirds of the tongue via chorda tympani.

Finally, the facial nerve also carries axons of type GVA, general visceral afferent, which provide sensation to the soft palate and parts of the nasal cavity.

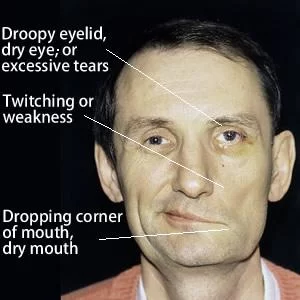

Symptoms of Facial Palsy

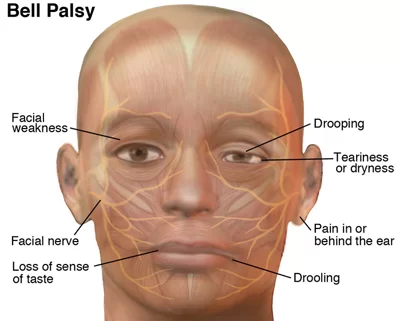

PALSY: Facial Muscle Paralysis

People may suffer from acute facial nerve paralysis, which is usually manifested by facial paralysis. Bell’s palsy is one type of idiopathic acute facial nerve paralysis, which is more accurately described as a multiple cranial nerve ganglionitis that involves the facial nerve, and most likely results from viral infection and also sometimes as a result of Lyme disease. Iatrogenic Bell’s Palsy may also be a result of an incorrectly placed dental local anesthetic (Inferior alveolar nerve block). Although giving the appearance of a hemiplegic stroke, its effects dissipate with the drug.

The onset of facial paralysis is sudden with Bell’s palsy and can worsen during the early stages. Symptoms will usually manifest and peak within 2-3 days, although it can take as long as 2 weeks. Common symptoms include, but are not limited to:

- Muscle weakness or paralysis

- Facial droop

- Impossible or difficult to blink

- Difficulty speaking

- Difficulty eating and drinking

- Nose runs

- The nose is constantly stuffed

- Difficulty breathing out of the nostril on the affected side

- Nostril collapse on the affected side

- Forehead wrinkles disappear

- Sensitivity to sound

- Excess or reduced salivation

- Facial swelling

- Drooling

- Diminished or distorted taste

- Pain behind ear

There are also some eye-related symptoms, which may include but are not limited to:

- Difficulty closing the eye

- Sensitivity to light

- Lower eyelid droop

- Tears fail to coat the cornea

- Brow droop

- Excessive tearing

- Lack of tears

When the facial nerve is permanently damaged due to a birth defect, trauma, or other disorder, surgery including a cross-facial nerve graft or masseteric facial nerve transfer may be performed to help regain facial movement. Facial nerve decompression surgery is also sometimes carried out in certain cases of facial nerve compression.

EXAMINATION-

Voluntary facial movements, such as wrinkling the brow, showing teeth, frowning, closing the eyes tightly (inability to do so is called lagophthalmos), pursing the lips, and puffing out the cheeks, all test the facial nerve. There should be no noticeable asymmetry.

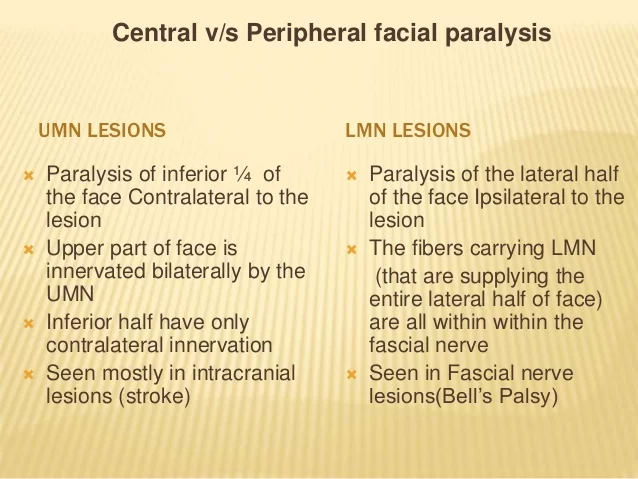

In a UMN lesion, called central seven, only the lower part of the face on the contralateral side will be affected, due to the bilateral control of the upper facial muscles (frontalis and orbicularis oculi).

LMN lesions can result in a CNVII palsy (Bell’s palsy is the idiopathic form of facial nerve palsy), manifested as both upper and lower facial weakness on the same side of the lesion.

Taste can be tested on the anterior 2/3 of the tongue. This can be tested with a swab dipped in a flavoured solution, or with electronic stimulation (similar to putting your tongue on a battery).

Corneal reflex. The afferent arc is mediated by the General Sensory afferents of the Trigeminal Nerve. The efferent arc occurs via the Facial Nerve.

The reflex involves consensual blinking of both eyes in response to the stimulation of one eye. This is due to the Facial Nerve’s innervation of the muscles of facial expression, namely Orbicularis oculi, responsible for blinking. Thus, the corneal reflex effectively tests the proper functioning of both Cranial Nerves V and VII.

FACIAL NERVE PALSY-

Facial palsy is a weakness or paralysis of the muscles of the face.

Whilst the majority of cases are idiopathic, termed Bell’s Palsy, there is a wide range of potential causes of facial palsy.

Bell’s palsy is a diagnosis of exclusion and hence all possible causes have to be excluded first prior to diagnosing Bell’s palsy. The majority of this article will discuss Bell’s Palsy and its associated clinical features and management.

RISK FACTORS

Facial ’s palsy remains a poorly understood condition. Many causative associations have been proposed, and the most universally accepted theory suggests a viral origin, yet no conclusive evidence is available at present.

The main risk factor for developing Bell’s palsy is known concurrent viral infection, such as HSV-1(HERPES SIMPLEX VIRUS 1), CMV (CYTOMEGALOVIRUS), and EBV (EBSTEIN VIRUS), whilst less common risk factors.

include diabetes mellitus and pregnancy.

CLINICAL FEATURE-

Patients with Bell’s Palsy will present with varying severity of painless unilateral lower motor neuron weakness of the facial muscles.

Depending on the severity and the ximity of the nerve affected, it can also result in:

Inability to close their eye (temporal and zygomatic branches)

Hyperacusis (nerve to stapedius)

Metallic taste (chorda tympani)

Reduced lacrimation (greater petrosal nerve)

DIFFERENCE BETWEEN THE UMN AND LMN LESIONS–

To distinguish clinically between an LMN cause and a UMN cause of the facial palsy, a patient with forehead sparing (i.e. no involvement to the occipitofrontalis muscle) will have a UMN origin to the palsy, due to the bilateral innervation of the forehead muscle).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The important differential diagnosis for facial palsy, other than Bell’s Palsy, include:

UMN causes, such as a stroke, SDH, or tumor

Will present with forehead sparing

- LMN CAUSES

- Infective such as acute otitis media, cholesteatoma, viral infection (including HSV-1, CMV, and EBV)

- Neoplasm (parotid malignancy)

- Trauma or iatrogenic

- Neurological (Multiple sclerosis or Guillain-Barré syndrome)

Diagnosis:

Most cases of Bell’s Palsy can be diagnosed clinically and no further investigations are required, unless any other clinical features are present that suggest another pathology.

Serology for HSV-1 and VZV can be performed, yet will unlikely alter future management if detected.

Treatment of Facial Palsy

Patient reassurance is essential, as most cases return spontaneously to full function. Eye care is one of the most important aspects of the management, ensuring the patient uses lubricating drops hourly and the potential for eye ointment at night and/or an eye patch.

Medical Treatment

All patients presenting within 72 hours of symptom onset should be started on oral steroids. Current NICE guidance recommends either:

Giving 25 mg twice daily for 10 days

Giving 60 mg daily for five days followed by a daily reduction in dose of 10 mg

The use of anti-viral agents is controversial.

A Cochrane Review found low-level evidence that the combination of anti-virals and corticosteroids is more effective in Bell’s palsy treatment; many centers currently treat Bell’s palsy with both.

SURGICAL REFERRAL

Referral to an ENT surgeon should be considered if there is any doubt over the diagnosis, recurrent or bilateral Bell’s palsy, or no sign of improvement after 1 month. There are surgical options available for patients who have persistent weakness or synkinesis. Synkinesis could be treated with botox injections whilst persistent weakness can be treated with the anterior belly of diagastric transfer, fascia lata sling, or cross-facial nerve grafting.

A referral to ophthalmology should be made if the cornea remains exposed after attempting to close the eyelid (House Brackmann grade of IV or more).

Complications

85% of cases will recover from Bell’s palsy, the majority of which make a full recovery with no evidence of residual symptoms. The factors that suggest a poor prognosis from facial palsy include:

- Complete palsy

- No signs of recovery within 3 weeks

- Age >60yrs

- Associated pain

- Ramsey Hunt syndrome

- Associated HTN, DM, or pregnancy

Physiotherapy Treatment for Facial Palsy

In the first couple of days to a week, after symptoms start, a physiotherapist will evaluate your condition, including:

Review your medical history, and discuss any previous surgery or health conditions

Review when your current symptoms started and what makes them worse or better

Conduct a physical examination, focusing on identifying the patterns of weakness that are caused by Bell palsy

- Facial movements of the eyebrow

- Eye closure

- Ability to use the cheek in smiling

- Ability to use the lips in a pucker

- Ability to suck the cheeks between the teeth

- Raising the upper lip

- Raising or lowering the lower lip

Your physiotherapist will immediately:

- Educate you about how to protect your face and your eye

- Show you how to manage your daily life functions while you have facial paralysis

- Explain the expected path to recovery, so that you will know the signs and symptoms of recovery

- Evaluate your progress, and determine whether you need to be referred to a specialist if progress is not being made The first priority is to protect your eye. The inability to completely and quickly

- close your eye makes the eye vulnerable to injury from dryness and debris. Debris can scratch the cornea—the transparent front part of the eye that covers the iris, pupil, and front chamber of the eye—and could permanently harm your vision. physical therapist will immediately show you how to protect your eye, such as:

- Using self-made and commercial patches

- Setting a regular schedule for refreshing eye fluids

- Carefully closing your eye with your fingers

- If you have partial facial movement, your therapist will teach you a few general facial exercises to do at home. These exercises will help you learn to move the weak side of your face and help you use both sides of your face together. One of the exercises is a gentle blowing action through your lips.

Exercise Video Of Facial Muscle :

DURING RECOVERY

Physical therapists will help you regain the healthy pattern of movements that you need for facial expressions and function. Recovery can be challenging because:

Normally, the ability to make facial expressions and many facial movements is “automatic”;—that is, you’re born with this ability and never had to think about it before Unlike other muscles in your body, the facial muscles do not have sensors that tell your brain all of the necessary “details” about how to move Physical therapist will be your coach throughout this challenging time, guiding you through special exercises that are designed to help you relearn facial movements based on your particular movement problems. Your exercises may change over the course of recovery:

“Initiation” exercises. In the early stages, when you might have difficulty producing any facial movement at all, your therapist will teach you exercises that cause (“initiate”) facial movement. Your therapist will show you how to position your face to make it easier to move (called “assisted range of motion”) or how to “trigger” the facial muscles to do what you want them to do.

“Facilitation” exercises. Once you’re able to initiate movement of the facial muscles, your therapist will design exercises to increase the activity of the muscles, strengthen the muscles, and improve your ability to use the muscles for longer periods of time (“facilitate” muscle activity).

Movement control exercises. the therapist will design exercises to:

- Improve the coordination of your facial muscles

- Refine your facial movements for specific functions, such as speaking or closing your eye

- Refine movements for facial expressions, such as smiling

- Correct abnormal patterns of facial movement that can occur during recovery

- To work on coordinating your facial muscles, you’ll need to have a sufficient level of activation of facial muscles first.

RELAXATION- During recovery, you might have facial spasms or twitches. Your physical therapist will design exercises to reduce this unwanted muscle activity. The therapist will teach you how to recognize when you are activating the facial muscle and when the muscle is at rest. By learning to contract the facial muscle forcefully and then stop, you will be able to relax your facial muscles at will and decrease twitches and spasms.

AFTER RECOVERY-

Some people might have greater difficulty moving their faces after a period of improvement in facial movement, which can make them worry that facial paralysis is returning. However, the actual recurrence of facial paralysis of the Bell Palsy type is uncommon.

New difficulty in moving the face is more likely the result of increasing the strength of the facial muscles without improving the ability to coordinate and control the movement. To keep this from happening, a physical therapist will show you what facial movements you should avoid during recovery. For instance, the following might lead to abnormal patterns of facial muscle use:

Trying to make the biggest facial movement or muscle contraction that you can, such as smiling as much as you can

- Chewing gum with great force

- Blowing up a balloon with all of your effort to work the facial muscles

The therapist will coach you to use your face as naturally as possible, without trying to restrict facial expressions because they look “different.”

NEUROMUSCULAR RETRAINING (NMR)

NMR involves the use of subtle but critically important exercises to teach and retrain the brain to coordinate the facial muscles more effectively and efficiently.

BENEFITS OF NMR

NMR re-teaches facial paralysis patients which muscles are required to move different parts of the face. This type of physical therapy enables a patient’s brain to reconnect facial muscles and corresponding facial movements. It teaches patients how to isolate facial muscles, uses only the correct muscles to make their desired facial movements, and suppress muscles that otherwise cause unwanted facial movements.

VIABLE CANDIDATE FOR NMR

Patients dealing with Bell’s palsy or other viral infections of the facial nerve often recover on their own completely and spontaneously within about three months of an initial diagnosis. For those who do not fully recover, it is possible that the facial nerve will heal improperly, which causes spontaneous, unwanted facial movements (or synkinesis). For example, when a Bell’s palsy patient tries to smile, his or her eye may twitch at the same time. In this scenario, the patient does not require additional strength in the facial muscles. Instead, he or she needs to improve facial muscle coordination to prevent facial muscles from flexing out of sequence – something that causes distorted facial movements.

MANUAL MASSAGE

Manual massage involves a series of different massage techniques. The goal of manual massage is to decrease facial muscle tightness and improve flexibility and range of motion. Initially, manual massage techniques may be performed by physical therapists, but the therapist ultimately will teach a patient the techniques so he or she can perform them regularly at home.

19 Comments