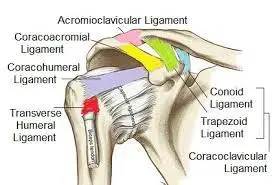

Shoulder Joint Ligament

The ligaments of the shoulder are strong, flexible bands of connective tissue. They are essential for passive shoulder stability because they maintain the shoulder joints, attach bone to bone, and restrict mobility.

The shoulder is composed of several joints, each of which is supported by numerous ligaments. The ligaments in the shoulder aid in pulling the bones together, supporting and strengthening the joint capsules, and preventing dislocation.

Tough bands of fibrous connective tissue with robust collagen fibers make up ligaments. Collagen fibers in ligaments become less elastic and more rigid with age, as they become straighter instead of wavy. This increases their vulnerability to injury.

In this article, we examine the various shoulder ligaments, including their location, functions, significance, and potential problems.

What is a Shoulder Joint Ligament?

Shoulder joint ligaments are strong bands of connective tissue that support to stabilize the joint and control dislocation. There are several essential ligaments in the shoulder.

The shoulder joint is a ball-and-socket joint, which indicates the round head of the humerus bone fits into the shallow glenoid fossa of the scapular bone. Yet, unlike some other ball-and-socket joints, the shoulder joint is very unstable due to its shallow socket. This instability allows for a wide range of movement, but it also makes the joint more easy to dislocate.

The shoulder ligaments are the primary tissues that give passive shoulder stability. Shoulder ligaments contribute to:

- Maintain shoulder stability.

- Strengthen joint capsules.

- Maintain the shoulder’s position.

- Reduce the possibility of shoulder dislocation.

- Limit the mobility of the bones at the joints.

Shoulder Joint Ligament: Anatomy and its Function

The shoulder ligaments work together to connect the humerus (upper arm bone), scapula (shoulder blade), clavicle (collar bone), and sternum (breast bone) via several joints.

- The glenoid-humeral joint: The glenoid fossa, a portion of the scapula, and the humeral head form the glenoid-humeral joint. A ball and socket joint is most often known as the shoulder joint.

- Acromioclavicular Joint: the junction of the clavicle and the acromion, a portion of the shoulder blade.

- Sternoclavicular joint: the junction of the sternum and clavicle.

These joints move when the arm is moved, especially when it is raised above the head, and the shoulder ligaments have an important role in regulating this movement.

The main Shoulder Joint Ligament includes:

- Glenohumeral Ligaments

- Coracohumeral Ligament

- Coracoclavicular Ligament

- Coracoacromial Ligament

- Acromioclavicular Ligament

- Transverse Humeral Ligament

- Sternoclavicular Ligaments

- Costoclaviculare Ligament

- Interclavicular Ligament

Glenohumeral Ligament

One of the most significant sets of shoulder ligaments at the glenohumeral joint is the glenohumeral ligaments.

The superior glenohumeral ligament, medial glenohumeral ligament, inferior glenohumeral ligament, and spiral glenohumeral ligament are the four glenohumeral ligaments located on the front of the shoulder joint, however, not every person possesses all four. They join the glenoid cavity on the scapula bone to the humerus bone in different locations.

Function: Especially during shoulder abduction, adduction, and external rotation, the glenohumeral ligaments contribute to improved stability at the front of the joint and stabilization of the glenohumeral joint capsule. Anteroinferior shoulder dislocation is less common when all four ligaments are present.

The Superior Glenohumerus Ligament(SGHL):

Origin: the top of the glenoid fossa, close to the coracoid process’s root

Insertion: the upper part of the humerus’s lesser tubercle

Function: Supports the brachial tendon in the biceps.

The Inferior Glenohumeral Ligament Inferior(IGHL):

Origin: The glenoid fossa’s inferior (lower) edge

Insertion: the humerus’s anatomical neck, immediately above the lesser tuberosity

Function: The primary stabilizer of the shoulder during abduction and the strongest of the four glenohumeral ligaments.

The Medial Glenohumeral Ligament (MGHL):

Origin: the glenoid fossa’s medial (inner) edge

Insertion: inferior region of the humerus’s smaller tubercle

Special Features: also known as the Ligamentum Middle Glenohumeral.

The Spiral Glenohumeral Ligament(SpGHL):

Origin: Infraglenoid tubercle

Insertion: Humeral lesser tubercle with subscapularis tendon.

Function: Strengthens the capsule of the anterior joint. The least common glenohumeral ligament is the spiral ligament.

Coracohumeral Ligament

The broad shoulder ligament known as the coracohumeral ligament (CHL) is separated into the superior and inferior bands.

Function: The coracohumeral ligament serves to protect the head of the humerus and to strengthen and stabilize the upper portion of the glenohumeral joint capsule.

Superior Band

Origin: the base of the coracoid process’s lateral (outside) border.

Insertion: the supraspinatus tendon and the greater tubercle of the humerus.

Inferior Band

Origin: the lateral surface of the coracoid process base.

Insertion: the humerus’s lesser tubercle.

Acromioclavicular Ligament

The horizontal acromioclavicular ligament (ACL) joins the collarbone and shoulder blade. The superior and inferior acromioclavicular ligaments are its two constituent sections.

Function: The acromioclavicular ligament gives the AC joint horizontal stability and strengthens the joint capsule’s superior, or top, part.

Superior Acromioclavicular Ligament

Origin: The acromion’s superior (upper) surface.

Insertion: the lateral (outside) aspect of the clavicle.

Inferior Acromioclavicular Ligament

Origin: The inferior (lower) surface of the acromion is the origin of the inferior acromioclavicular ligament.

Insertion: lateral end of the clavicle.

Coracoclavicular Ligament

The shoulder blade and collarbone are additionally joined by the coracoclavicular ligament (CCL). It consists of the trapezoid ligament in the front and the conoid ligament at the back, two tiny but powerful components. The thinner trapezoid ligament is medial to the conical-shaped conoid ligament.

Function: The coracoclavicular ligament maintains the scapula linked to the clavicle, giving your shoulders a square shape. It is firm and can support a heavy load. In addition to transmitting weight from the upper limb to the axial skeleton, it offers vertical stability at the ACJ.

Conoid Ligament

Origin: the root and posterior surface of the scapula’s coracoid process.

Insertion: on the clavicle’s inferior surface, the conoid tubercle

Ligament Trapezoid

Origin: The coracoid process’ superior (upper) surface.

Insertion: Under the lateral clavicle, on the trapezoid line.

Coracoacromial Ligament

The coracoacromial ligament (CAL), a powerful triangular-shaped ligament, is one of the main shoulder ligaments. The coracoacromial arch, which forms an arch across the top of the glenohumeral joint, is formed by the connection of two sections of the scapula. This arch is beneath the rotator cuff tendons.

Function: The coracoacromial shoulder ligament enhances shoulder stability, guards against superior glenohumeral dislocation, and protects the humeral head. Additionally, it transfers loads over the scapula.

Origin: the coracoid process’s lateral edge

Insertion: the acromion’s inferior anterolateral surface

Impingement syndrome is frequently caused by the coracoacromial ligament thickening, which decreases the subacromial space.

Transverse Humeral Ligament

The transverse humeral ligament (THL), also known as Brodie’s Ligament, differs from the other shoulder ligaments in that it does not cross a joint. Instead, it connects the greater and lesser tubercles at the humeral head.

The transverse humeral ligament secures the long head of the biceps tendon in the intertubercular groove.

Origin: The greater tubercle of the humerus.

Insertion: Humerus’s lesser tubercle (intertubercular sulcus)

Sternoclavicular Ligaments:

The sternoclavicular ligaments (SCL) are the ligaments that link the collarbone to the breastbone.

This shoulder ligament is divided into two parts: the anterior sternoclavicular ligament and the posterior sternoclavicular ligament, located at the front and rear of the joint.

Function: The sternoclavicular ligaments assist to stabilise the sternoclavicular joint by reinforcing the joint capsule. They restrict the clavicle’s anterior/posterior translation, preventing it from shifting too far forward and backward.

Anterior Sternoclavicular Ligament(ASL):

Origin: The medial end of the clavicle.

Insertion: Anterosuperior manubrium insertion of the sternum.

Function: Limits excessive superior displacement at the joint and opposes clavicle upward rotation and lateral movement.

Posterior Sternoclaviculare Ligament (PSL):

Origin: The posterior surface (rear) of the sternal end of the clavicle.

Insertion: Posterosuperior manubrium.

Function: Restricts clavicle downward rotation and medial movement.

Costoclaviculare Ligament:

The costoclavicular ligament (CCL) is a small, flat, but highly strong ligament that joins the first rib to the collar bone. Because of its form, it is also known as Halsted’s Ligament or the rhomboid ligament.

Function: The Costoclavicular ligament is the primary sternoclavicular joint stabilizing component, supporting the inferior side under the sternoclavicular joint. It restricts clavicle and shoulder girdle elevation as well as anteroposterior (forward and backward) mobility at the sternoclavicular joint.

Origin: The superior (upper) surface of the first rib and its cartilage.

Insertion: costal tuberosity on the clavicle’s inferomedial aspect.

Interclavicular Ligament:

The interclavicular ligament (ICL) is a flattened band that runs along the top surface of the sternoclavicular joint, covering the spaces between both clavicles.

Function: The interclavicular shoulder ligament strengthens the top of the sternoclavicular joint capsule. It prevents clavicular dislocation and excessive downward glide with shoulder depression.

Origin: The upper section of one clavicle’s sternum.

Insertion: The upper sternal end of the opposite clavicle.

Injury to the Shoulder Joint Ligament

The following are the most common causes of shoulder ligament injuries:

- Direct trauma: to the shoulder, such as a fall, is most prevalent in teenagers.

- Repetitive Friction: occurs on the ligament as a result of repeated overhead activities, causing irritation and wear and tear. The condition is more frequent in adults over the age of 60.

Shoulder ligament injuries are frequently accompanied by additional shoulder problems such as:

- Shoulder bone: injuries include fractures and dislocations.

- Shoulder Impingement Syndrome: is characterized by a constriction of the subacromial space.

- Tears in the labrum: injury to the unique cartilage ring on the shoulder socket.

Sings and Symptoms of shoulder Joint ligament injuries

The following are common signs of shoulder ligament injuries:

- Shoulder Aches: Shoulder discomfort worsens with arm motions, especially lifting your arm above your head or shrugging your shoulders.

- Inflammation and swelling: In the area around the shoulder.

- Restricted Daily Activity: Due to discomfort and stiffness, daily living activities are limited. Sleep may also be affected.

- Instability: the shoulder may experience weakness. People with shoulder ligament problems frequently report they don’t trust their shoulder and fear it may pop out.

- Deformity: If the ligament has ruptured, there will be an evident visual deformity at the affected shoulder joint.

Diagnosis of the Shoulder Joint Ligament

A shoulder ligament injury will be diagnosed based on the following criteria:

- Symptoms history.

- Comparing your damaged and uninjured shoulders.

- Shoulder physical examination, including a range of motion and strength testing.

- X-rays are used to detect any bone abnormalities.

- MRI is used to detect soft tissue disorders.

Treatment for the Shoulder Joint Ligament

Shoulder Ligament Tears Treatment Include:

The degree of your shoulder ligament tear will determine the treatment:

Grade 1: If the shoulder ligament rupture is microscopic or extremely minor (Grade 1), the problem can be treated with rest, ice, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medicine to ease uncomfortable symptoms.

Grade 2: In the case of a partly torn shoulder ligament tear (Grade 2), a sling may be worn for 3-4 weeks in addition to the preceding therapeutic measures to permit for appropriate healing of the shoulder ligament.

Grade 3: In the case of a severed shoulder ligament tear (Grade 3), surgical surgery to restore the ligament may be necessary. Most of the time, the operation may be done arthroscopically in an outpatient environment using little poke-hole incisions, and you can go home the same day.

When a shoulder ligament is injured, it is critical to reestablish the shoulder’s stability to limit the risk of subsequent damage. One of the most effective methods to do this is through a rehabilitation program that focuses on:

- Rotator Cuff Strengthening: exercises to increase the active stability of the rotator cuff muscles at the shoulder.

- Scapular Stabilisation: exercises to increase shoulder blade stability and control.

Exercises for the Shoulder Joint Ligament Rehabilitation

Physical therapy will be necessary if you have a Ligament injury to help you rebuild shoulder strength and range of motion.

Here are some examples of common exercises and stretches you can face on the way to recovery.

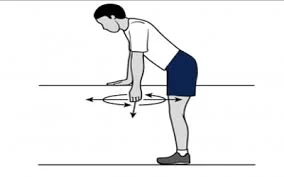

Pendulum Swinging

- Place the hand of your undamaged arm on the side of a table, stable chair, or railing for support.

- Allow the affected arm to swing freely and gently lean forward without rounding the back. Then, move this arm forward and back softly.

- Move your arm in and out (side-to-side) starting in the same position.

- Moving your arm in little circles, begin in the same position. Begin by going clockwise, then reverse and go anticlockwise.

- Rep the exercise with the other arm.

Lying Down and Lifting Arms

- Lie on your back with your wounded arm propped up on a towel. Lift your arm straight up without any assistance.

- If you can’t, raise the damaged arm using your non-injured arm. Maintain the arm up with the elbow straight for as long as possible without assistance.

- With the support of the opposite arm, bring the arm back down to your side.

- As your arm strength increases, you will be able to raise and lower your arm with less assistance.

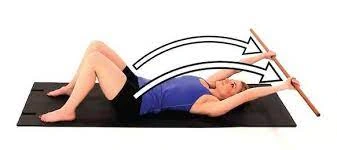

Lying Down, Flex Shoulder

- Place a rolled towel over your injured arm while you lie on your back.

- Raise your arm slowly towards the sky. Swing your arm forward and backward slowly.

- Begin with gentle, painless movements. Increase the size of these arcs as your strength increases, but only if it doesn’t hurt.

- Continue for up to five minutes straight, or until your arm becomes too fatigued to handle any more.

Laying Flat and using Weights to Flex the Shoulder

- Place a rolled towel over your injured arm while you lie on your back.

- Raise your arm slowly towards the sky but this time, hold a 500 ml water bottle or a small weight. Begin with a little motion.

- Expand these arcs as you gain strength and if it doesn’t hurt. Continue for up to five minutes straight, or until your arm becomes too fatigued to handle any more.

Crossover Arm Stretch

Straighten your back and let your shoulders relax. If you need to calm down, take a few deep breaths. Reach as far as you can with the affected arm, extending it over your chest but below your chin. Holding the affected arm’s elbow area with the good arm helps. This exercise should feel like a stretch rather than hurt. With the other arm, perform the exercise again.

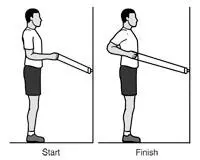

Standing Row

- For this activity, create a three-foot loop by tying the ends of a stretch band together.

- Face the steady item, such as a doorknob, with one end of the loop attached to it.

- Make sure there is little to no slack in the band by standing far enough away and holding the other end in one hand.

- Pull the elbow back while keeping your arm close to your body and bend at a 90-degree angle. With the other arm, perform the exercise again.

Internal Rotation

This exercise uses a stretch band that is knotted at both ends to form a three-foot loop, just like a standing row. Hold the band in the hand of your afflicted arm while standing to the side and securing one end of the loop to a stable object, such as a doorknob.

Keep your elbow close to your body and flex it to a 90-degree angle. Next, cross the forearm over the body’s stomach. With the other arm, perform the exercise again.

Prevention for the Shoulder Joint Ligament

Sustaining the integrity of the ligaments in your shoulder joint is essential to preventing pain and discomfort, there are a few actions you can take to prevent this:

- Focus on strengthening the rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers regularly.

- Balance is essential, so make sure to do core and back strengthening activities. Powerful posterior muscles provide a counterbalance to robust chest muscles, avoiding imbalances and incorrect postures that could cause ligament strains.

- Stretching: By increasing the range of motion and flexibility, stretching the shoulders, upper back, and chest regularly lowers the risk of tears and overuse of the ligaments.

- Warm-up before exercise: Before beginning any physical activity, especially one that requires overhead motions, always warm up with some light aerobic and dynamic stretches.

- Safe lifting methods: To prevent overstressing the shoulder joint, learn and put into practice safe lifting techniques. When lifting, keep the object close to your body, bend your knees, and use your core.

- Keep your shoulders rounded and your back straight to prevent straining your ligaments. Maintain good posture by keeping your spine straight and your shoulders back and down.

- Pay attention to your body. Put an end to any pain or discomfort-causing activity. Excessive exercise could aggravate currently present ligament problems or cause new ones.

- Reduce the amount of time you spend doing repetitive overhead motions: Try to vary your activities throughout the day and take frequent pauses if your work or hobbies require repetitive overhead motions.

- Keep your weight in check: Carrying too much weight strains the shoulder joint and raises the possibility of ligament sprains.

- Think about using protective gear: Braces or padding may provide extra support and lower your chance of ligament injuries, depending on your activity.

Recall to get a correct diagnosis and treatment plan from a healthcare provider if you have ongoing shoulder discomfort, weakness, or instability. Prompt intervention helps avert possible difficulties and provide the best possible outcome.

FAQs

Which four shoulder ligaments are the primary ones?

Ligaments In The Shoulder are:

Coracohumeral Ligament

Glenohumeral Ligaments.

Coraco-acromial Ligament.

Coraco-clavicular Ligaments.

Can ligaments in the shoulders heal themselves?

Common sprains and strains, among other tendon and ligament problems, frequently recover without the need for surgery. Nevertheless, the procedure is frequently slow and leads to the development of inferior scar tissue, which takes years to regenerate into more useful tissue.

What is the process of treatment for shoulder ligament tears?

Ligaments can heal when the arm is kept in a sling to restrict shoulder movement. Physical rehabilitation exercises are frequently performed after this. Occasionally, surgery is required. A dislocated shoulder occurs when the ligaments that keep the shoulder bones together break and are unable to maintain the joint.

What is the healing period for shoulder ligaments?

Mild shoulder pain can take four to six weeks to fully resolve. Usually, it takes two weeks of doing exercises for shoulder pain to start getting better.

References

- Shoulder ligaments | ShoulderDoc. (n.d.). https://www.shoulderdoc.co.uk/article/1179

- Shoulder Pain Explained. (n.d.). Shoulder ligaments: Anatomy, function & injuries. Shoulder-Pain-Explained.com. https://www.shoulder-pain-explained.com/shoulder-ligaments.html

- Bhuta, A. I. (2018, May 11). Anatomy of the shoulder – Part 2 (Ligaments and Capsules) – MUJO. MUJO. https://www.mujofitness.com/blog/2018/05/11/anatomy-of-the-shoulder-part-2-ligaments-and-capsules/