Anatomy Of Veins In Legs

Introduction

Movement and locomotion depend on the legs. The venous system is one of the vital organs in charge of maintaining adequate circulation in the lower limbs.

It is of the utmost importance to comprehend the structure and operation of leg veins in order to maintain ideal venous health. The goal of this page is to give a thorough explanation of the anatomy and classification of leg veins.

The Function and Categorization of Veins

Blood vessels that transport blood to the heart are called veins (from the Latin vena). On the other side, arteries complete the circulatory system by removing blood from the heart. A vein’s diameter can vary from one millimeter to one and a half centimeters.

Valves that return blood from the body typically convey oxygen-poor (deoxygenated) blood, with a few notable exceptions, such as the veins that bring blood from the lungs to the heart. Veins come in two varieties: deep veins and superficial veins.

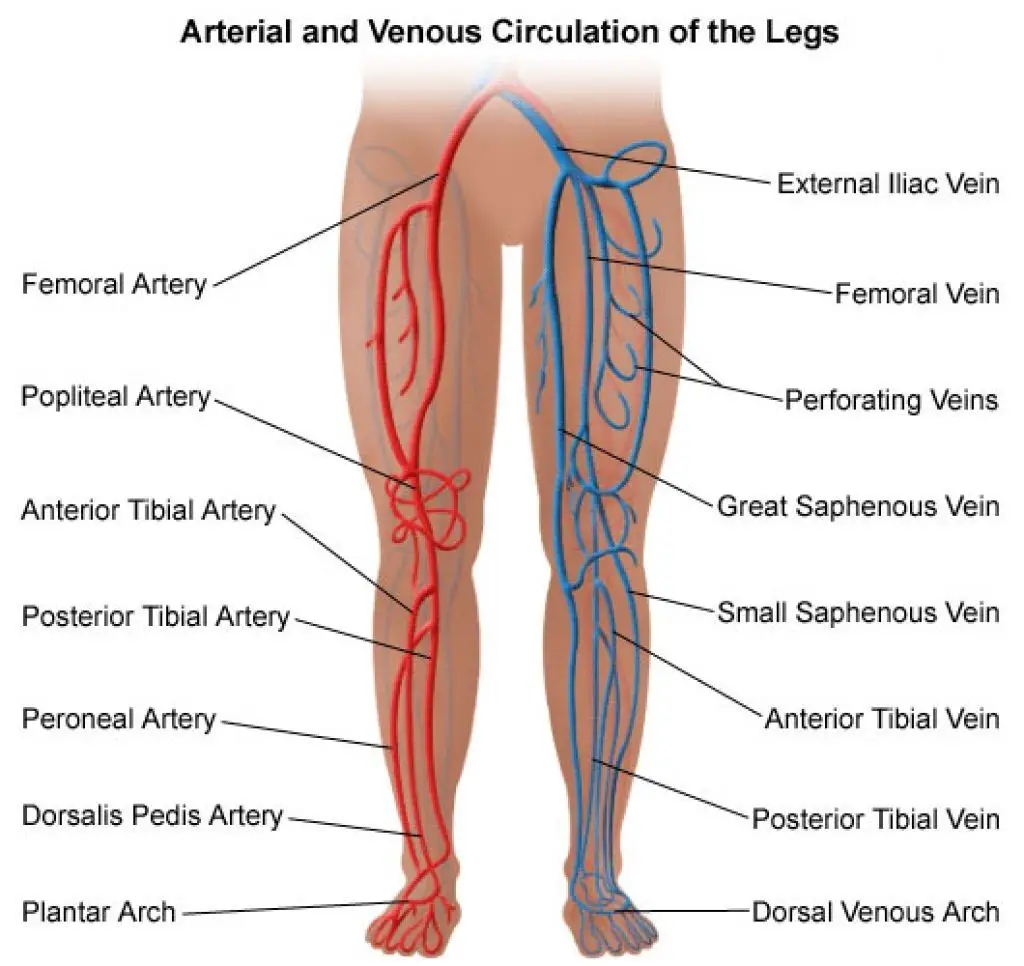

Anatomy of Leg Veins

Blood is returned to the heart from the lower extremities through the intricate leg vein system. It is made up of three main vein types, each of which has a different purpose and location in the leg.

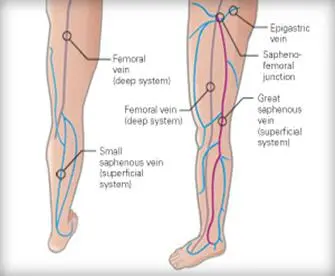

When superficial veins, which are found just below the skin’s surface, grow or twist, they become clearly apparent. The great saphenous vein (GSV) and the small saphenous vein (SSV) are the two primary superficial veins.

Extending from the foot to the groin, the GSV is the longest vein in the body.

The SSV extends from the back of the ankle to the rear of the knee along the back of the calf. It has the potential to generate varicose veins, much as the GSV.

Your leg muscles are home to deep veins. Most of the blood is returned to the heart via them. The following are the main deep veins in the leg:

- The anterior tibial vein, which passes through the lower leg’s front

- The vein behind the lower leg is called the posterior tibial vein.

- The peroneal vein, which runs parallel to the lower leg,

- The vein beneath the knee is called the popliteal vein.

- The vein in the thigh called the femoral

Blood may travel from the surface of your skin to the deepest part of your leg muscles thanks to perforator veins, which join the superficial and deep veins. Maintaining appropriate venous blood flow and avoiding blood pooling in the lower extremities are made possible by perforator veins.

Blood must defy gravity in leg veins in order to return to the heart. One-way valves, which stop blood from flowing backward, make this feasible. These valves effectively push blood upward when they are operating correctly. Varicose veins can develop in the legs as a result of blood pooling there if these valves weaken or collapse.

What causes the veins’ blood to flow?

For your veins to assist in moving your blood in the proper direction, an outside force is required. Breathing on your own is one such energy. Your diaphragm contracts and your lungs expand, creating a suction force that helps your veins pump blood with less oxygen towards your heart. The movement of the muscles in your body, particularly the legs, is another force. In actuality, the muscles in your legs are essential for your blood to overcome gravity and ascend from your feet and legs back to your heart. Your calves’ muscles are referred to be your “second heart” for this reason.

The “second heart”

It may surprise you to learn that the muscles in your lower legs function as a strong pump, forcing blood from your deep veins. Every time you walk, this “second heart,” also known as your peripheral heart, beats. The deep veins at the bottom of your foot are compressed by your body weight as you plant it on the ground. Consequently, any blood therein is forced upward towards your calf by those veins.

The deep veins in your calf are then compressed by your calf muscles when you elevate your heel. Your blood continues to rise towards your thighs and upward. The blood in your lower limbs and feet can overcome gravity and return to your heart thanks to this amazing mechanism.

Your second heart only begins to beat when your legs move, in contrast to the heart located in your chest. Furthermore, its heart-pounding tempo adapts to the speed at which your legs move. Your calf muscles will thus contract faster during a run than during a stroll. Your second heart keeps your blood moving and completes its circuits throughout your body, no matter how quickly. Your organs and tissues thus continue to get the oxygen and nourishment they need to perform at their peak.

Leg Venous Structure

The lower limb’s venous anatomy may be compared to an upside-down tree, with blood starting in superficial venous capillaries and traveling upward and inward through progressively wider veins to reach the heart. Two vein systems that run parallel to one another carry out this function. There are two types of vein systems in the legs: the superficial vein system, which runs in the fat layer between the muscle compartments plus the skin, and the deep vein system, which runs within the muscles.

The vena cava, the biggest vein in the body that is directly related to the heart, is reached by deep veins. At certain significant “collection points,” such as the back of the knee and the groin, where the Great and Lesser Saphenous veins drain blood, or throughout the legs via shorter, smaller bridge veins known as perforator veins, the superficial veins empty into the deeper veins.

Several prominent perforators have been recognized and given names, including Boyd, Cockette, Dodd, and Hunter. There are thought to be between 90 and 150 perforators on each leg. Because they move blood straight from the superficial veins to the deep veins, perforator veins—also referred to as communicating veins—connect the superficial and deep venous systems in parallel, like the ladder rungs of a ladder linking the two side rails.

Lower limb superficial veins

The lower limb’s two primary superficial veins have been identified as the:……

- Great saphenous vein

- Small saphenous vein

- Great saphenous vein

- Great saphenous vein (Vena saphena magna)

- Femoral vein (Vena femoralis)

- Great saphenous vein

- Vena saphena Magna

- 1/2

- Synonyms: Long saphenous vein

The longest vein in the human body is the great saphenous vein, also known as the long saphenous vein. It continues from the foot’s medial marginal vein and finishes distal to the inguinal ligament in the femoral vein.

It crosses the distal part of the tibia anteroposteriorly after ascending superficially to the medial malleolus. It travels up the medial portion of the thigh and into the saphenous opening, a hole in the fascia lata of the thigh, after going behind the medial tibial and femoral condyles. 2.5 to 3.5 centimeters inferolateral to the pubic tubercle, it opens into the femoral vein.

Throughout its length in the thigh, the great saphenous vein runs alongside branches of the medial femoral cutaneous nerve.

There are 10–20 venous valves in it, more than in the leg.

Via perforating veins, the great saphenous vein is intricately linked to the small saphenous vein and the deep veins of the lower leg. The anterior and posterior tibial veins, as well as the small saphenous vein, send and receive blood to the great saphenous vein, which is located just distal to the knee. The great saphenous vein’s major tributaries join it in the thigh, close to where it meets the femoral vein. These tributaries number six:

- The superficial portion of the posteromedial area of the thigh is drained by the thigh’s posteromedial vein, also known as the accessory vein.

- A continuation of the anterior veins in the distal thigh, the anterior femoral cutaneous vein traverses the femoral triangle and opens into the great saphenous vein.

- The superficial epigastric vein travels via the saphenous aperture, draining the inferior abdominal wall and opening into the great saphenous vein.

- Additionally draining the inferior abdominal wall, the superficial circumflex iliac vein joins the great saphenous vein at the saphenous orifice.

- The superficial external pudendal vein exits at the saphenous aperture into the great saphenous vein and drains a portion of the labia or scrotum.

- At the saphenous aperture, the deep external pudendal vein runs parallel to the great saphenous vein.

Small saphenous vein

- Small saphenous vein (Vena saphena parva)

- Small saphenous vein (Vena saphena parva)

- Small saphenous vein

- Vena saphena parva

- 1/2

- Synonyms: Short saphenous vein

The lateral marginal vein continues into the tiny saphenous vein, also known as the short saphenous vein. In the distal portion of the calf, it ascends between the superficial and deep fascia and passes lateral to the calcaneal tendon. It passes through the deep fascia at the calf’s midline before rising superficially to the gastrocnemius muscle.

The small saphenous vein appears above the deep fascia at the intersection of the proximal and intermediate thirds of the calf. The gastrocnemius muscle’s heads are then crossed by it. Three to seven and a half centimeters above the knee joint, it ends in the popliteal vein inside the popliteal fossa.

The leg’s tiny saphenous vein is located close to the sural nerve and has seven to thirteen valves. The small saphenous vein in the leg gets several cutaneous tributaries from deep veins on the dorsum of the foot. It communicates with the great saphenous vein with a multitude of branches.

Deep veins of the lower limb

Based on their location, the lower limb’s deep veins may be divided into four major groups:

- Veins of the foot

- Veins of the leg

- Vein of the knee

- Veins of the thigh

- Veins of the foot

- There are two primary kinds of deep veins in the foot:

- Plantar veins, which drain the foot’s bottom or plantar surface

- veins called dorsal veins drain the upper or dorsal surface of the foot.

- Plantar digital veins are formed when venous plexuses in the toes’ plantar regions unite. Four plantar metatarsal veins are formed by the union of these veins with their dorsal counterparts, the dorsal digital veins. Four plantar metatarsal veins are formed by the union of these veins with their dorsal counterparts, the dorsal digital veins. The deep plantar venous arch is formed by these veins as they proceed proximally via the intermetatarsal gaps. This arch is where the lateral and medial plantar veins begin.

There is also a dorsal venous arch, which is made up of the dorsal and plantar digital veins as well as the dorsal metatarsal veins.

Veins of the leg

- Anterior tibial vein (Vena tibialis anterior)

- Posterior tibial vein (Vena tibialis posterior)

- Anterior tibial vein

- Vena tibialis anterior

- 1/2

The venae comitantes, or companion veins, of the dorsal pedis artery, give rise to the anterior tibial veins.

The medial and lateral plantar veins combine to produce the posterior tibial veins, which run parallel to the posterior tibial artery. The posterior tibial veins receive the drainage of calf muscle veins. Additionally, they get connections from the fibular and superficial veins.

Alongside the fibular artery, the medial and lateral plantar veins also constitute the fibular veins. They take tributaries from veins draining the soleus muscle as well as superficial veins.

Vein of the knee

The popliteal vein passes through the adductor magnus muscle and changes into the femoral vein as it exits the popliteal fossa. It is medial to the popliteal artery in terms of distance. It is superficial to the gastrocnemius muscle between its two heads, and proximally it is posterolateral to it.

The popliteal vein often has several tributaries and four or five valves. It receives drainage from the tiny saphenous vein, two muscular veins from each head of the gastrocnemius muscle, and the three major veins of the leg.

Veins of the thigh

- Femoral vein

- Vena femoralis

- 1/3

- Synonyms: none

The popliteal vein continues as the femoral vein, which runs parallel to the femoral artery. The external iliac vein starts from the adductor magnus muscle’s opening and finishes posterior to the inguinal ligament.

There is variability in its connection to the femoral artery. It is situated posterolateral to the artery in the distal adductor canal, posterior to the artery in the proximal canal, and near the apex of the femoral triangle. It is located medial to the femoral artery within the base of the femoral triangle. It typically contains four or five valves and is housed inside the femoral sheath’s main compartment.

Tributaries of the femoral vein include:

- the medial circumflex vein

- lateral circumflex vein

- great saphenous vein

- Drainage occurs 4–12 cm distal to the inguinal ligament in the profunda femoris vein.

- Seen as the deep vein of the thigh, the profunda femoris vein is situated superficially to the profunda femoris artery.

The profunda femoris vein empties into the thigh muscles after veins associated with the profunda femoris artery’s perforating branches empty into it. The profunda femoris vein occasionally has tributaries in the medial and lateral circumflex veins.

Which conditions impact the vein system?

Your venous system may be impacted by many conditions. Among the most popular ones are:

- DVT, or deep vein thrombosis: Usually in your leg, a deep vein becomes clothed with blood. There’s a chance that this clot will go to your lungs and cause pulmonary embolism.

- Superficial thrombophlebitis: A blood clot forms in an irritated superficial vein, generally in your leg. Thrombophlebitis is usually not as dangerous as DVT, however, it can happen infrequently when the clot moves to a deep vein and causes DVT.

- Varicose veins. Visible swelling occurs in superficial veins close to the skin’s surface. This occurs when vein walls deteriorate or one-way valves malfunction, enabling blood to flow backward.

- Chronic venous insufficiency: One-way valve malfunction causes blood to pool in your legs’ superficial and deep veins. Chronic venous insufficiency is comparable to varicose veins in that it typically produces additional symptoms, such as coarse skin texture and, in rare circumstances, ulcers.

Causes of Varicose Veins

Age, heredity, pregnancy, obesity, long periods of standing or sitting, and pregnancy all raise the chance of developing varicose veins. Venous valve dysfunction results in slow blood flow and increased vein pressure. Varicose veins are characterized by their characteristic bulging and twisting of veins due to increased pressure.

It is imperative to get medical assistance for varicose veins as failure to do so may result in severe problems such as leg ulcers, deep vein thrombosis, and venous insufficiency. Patients in the Houston region may get healthier, more comfortable legs by seeking the expertise of Premier Vein & Vascular Centre in Katy, Texas, which specializes in the diagnosis and treatment of vein diseases.

What signs and symptoms correspond to a vein problem?

Although venous conditions can present with a wide range of symptoms, some typical ones are as follows:

- inflammation or swelling

- tenderness or pain

- veins that feel warm to the touch

- a burning or itching sensation

In your legs, these sensations are particularly prevalent. See your doctor if you experience any of them and they don’t get better within a few days.

They are capable of venography. In order to create an X-ray image of a specific location, your doctor will inject contrast dye into your veins during this treatment.

Tips for healthy veins

To maintain the strength and appropriate operation of your vein walls and valves, adhere to these tips:

- Engage in regular exercise to maintain blood flow in your veins.

- Maintaining a healthy weight lowers your chance of developing high blood pressure. The increased pressure from high blood pressure over time might damage veins.

- Steer clear of prolonged standing or sitting. Make an effort to shift positions frequently during the day.

- When seated, try not to cross your legs for extended periods of time. Instead, alternate positions often prevent one leg from being elevated for an extended amount of time.

- Drink a lot of water when flying, and make an effort to get up and stretch frequently. You may promote blood flow by flexing your ankles even when seated.

Summary

The venous system of the lower extremities has a complicated and highly varied architecture. A uniform nomenclature that is maintained by an international consensus committee is necessary for effective communication and comprehension of the available treatment choices.

The leg veins consist of three types: communicating veins that link veins within the same venous system, perforating veins that pass through the fascia and connect the superficial and deep veins, and superficial and deep veins, which are identified by their relationship to the muscle fascia. Within the lower extremities, a system of bicuspid valves and muscle venous pumps maintains the flow from caudal to cephalad and from superficial to deep. Chronic venous blockage, muscle pump malfunction, valvular incompetence, or reflux can all cause systemic dysfunction.

Numerous alterations in the architecture of the venous wall are linked to primary varicose veins and may occur before reflux develops, leading to a number of fragile wall theories. By contrast, early thrombus adhesion to the valve cusp may cause post-thrombotic valvular injury. Chronic venous illness is characterized by a complicated interplay between hemodynamic dysfunction and architecture. More severe disease presentations may be linked to primary or secondary dysfunction of particular anatomic locations, such as the superficial veins, the popliteal vein, or the posterior tibial-peroneal veins. When treating a patient with chronic venous illness, a detailed understanding of the underlying anatomy and the processes causing hemodynamic failure is necessary.

FAQs

What are the symptoms of vein problems in the legs?

Swelling in the ankles or legs.

Uneasy, itchy legs or a tight sensation in your calves.

Walking pain that goes away as you rest.

Brown skin, frequently in the area of the ankles.

Veins that are variable.

Leg ulcers that might be challenging to heal at times.

How many veins are in your leg?

The Leg and Foot Cardiovascular Systems

The small, great, and anterior tibial veins are the three main leg veins into which blood from the dorsal venous arch enters. The great saphenous vein draws blood from the tissues in the leg as well as the thigh as it ascends through it on the medial side.

Is walking good for varicose veins?

Since walking is a gravity-dependent exercise that primarily employs your legs, it’s one of the finest methods to enhance circulation generally and in particular, circulation in your legs. Frequent walking can lower blood pressure in your arteries and veins, in addition to alleviating the symptoms of varicose veins.

Are normal veins visible in the legs?

Visible veins are often perfectly normal and shouldn’t raise any red flags. However, there may be cause for concern if you observe that your veins are suddenly more noticeable without any apparent reason. Vein disorders such as varicose veins may be indicated by visible veins in the arms or legs.

Why are feet called second heart?

The heart’s residual pumping force, the negative pressure generated in the veins while breathing, and the contraction of the calf and foot muscles—a muscle-vein system that is sometimes referred to as the second heart—all contribute to the movement of blood within the venous system.

References

Lower Extremity Venous Anatomy. Seminars in Interventional Radiology. https://doi.org/

Venous Drainage of the Lower Limb TeachMeAnatomy. https://teachmeanatomy.info/lower-limb/vessels/venous-drainage/

Veins of the lower limb. Kenhub. https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/veins-of-the-lower-limb

A Diagram of Leg Veins: Leg Vein Anatomy. Legacy Vein Clinic. https://legacyclinic.com/blog/a-diagram-of-leg-veins-leg-vein-anatomy/

Venous System Overview. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/venous-system