Bone Spurs (Osteophytes)

Understanding Bone Spurs (Osteophytes)

Definition and Overview of Bone Spurs

- Bone spurs, also called osteophytes, are bony growths that develop along joint surfaces

- They form as the body attempts to repair damaged joints or as a result of normal wear and tear.

- While sometimes asymptomatic, bone spurs can cause pain, inflammation, and loss of joint function if they rub against nerves or soft tissues.

Importance of Addressing Bone Spurs

- Left untreated, bone spurs may continue to grow larger over time

- They can lead to chronic inflammation and joint damage.

- Diagnosing and monitoring bone spurs early allows for conservative treatment options before surgery is required.

Common Locations of Bone Spurs

- Joints in the shoulders, knees, hips, heels, and spine are most often affected

- Spurs form as extra bone material near the injured or deteriorating joints

Causes of Bone Spurs

Aging and Degenerative Conditions

Aging and general wear and tear on the joints over time are considered the primary causes of bone spurs. As we get older, the cartilage that cushions joints gradually thins and becomes more prone to damage. In response, the body tries to stabilize the joints by initiating extra bone growth.

Osteoarthritis as a Leading Cause

Osteoarthritis is characterized by degeneration of cartilage and joint inflammation and causes the majority of bone spurs. Over time, the smooth cartilage that allows joints to glide steadily over each other erodes. This results in joint pain, swelling, and difficulty moving.

The body reacts by trying to repair the damaged cartilage through the proliferation of bone tissue. While the intention is stabilization, excess bone forms pieces that develop into painful bone spurs. Over 90% of bone spurs arise due to existing osteoarthritis. Any joints commonly affected by osteoarthritis – including knees, hips, hands, and spine – are at risk of bone spurs.

Degenerative Disc Disease and Bone Spurs

Degenerative disc disease shares similarities with osteoarthritis in that cartilage degeneration triggers the body’s attempt to heal itself through bone overgrowth. In degenerative disc disease, the flexible discs between the vertebrae lose elasticity and thickness over time. The worn-out discs become inflamed and hardened.

As the rigid discs cause abnormal friction with movement, the vertebral bones respond by creating stabilizing bone spurs. These spurs project along areas like the spine and neck where damaged discs are present. Degenerative disc disease most often affects the lower back and cervical spine.

Trauma and Joint Damage

Any kind of abrupt trauma or strain that tears ligaments, menisci cartilage, or joint capsules can initiate excess bone development. Common causes include sports collisions, falls, and accidents that severely twist or bend joints abnormally. Car accidents and combat injuries also frequently lead to areas of bone spurs.

The inflammation and swelling from ruptured structures irritate tissues surrounding the joint. This activates repair cells which precipitate irregular bony overgrowth. Previous fractures or surgical repairs can further the risk of bone spurs years later.

Joint Overuse and Repetitive Stress

While aging and pre-existing conditions account for most bone spurs, repetitive damage through overloading specific joints also provokes unnecessary bone formation over time. Athletes and people in active vocations tend to develop bone spurs regularly in commonly stressed joints.

Sports-Related Injuries and Bone Spurs

Certain sports place consistent pounding, twisting, rotating, or reaching forces on specific joints. Constant impact and unnatural movements contribute to cartilage deterioration in those areas. Sports most prone to bone spur development include basketball, tennis, baseball (pitching arms), running/jumping sports, and weightlifting.

Areas like the ankle, knee, hip, shoulder, and lower back endure the most movement and high-intensity loading. These regions in athletes and recreational weekend warriors often display bony growths and spurs over time.

Occupation-Related Factors

Some occupations naturally wear down joints faster due to repetitive heavy lifting, awkward positioning, kneeling, bending, squatting, or climbing. Common culprit vocations linked to bone spurs include construction workers, plumbers, electricians, carpet layers, mechanics, tile installers, landscapers, custodial staff, cargo handlers, and assembly line workers.

Poor Posture and Bone Spurs

Sustained poor posture during daily routines strains areas like the neck, shoulder, and spine unevenly. Slouching, hunching over computers, looking down frequently, and lifting with the back instead of the legs irritates disks and supporting joints.

This accelerates degeneration and prompts the growth of bone spurs as the body tries to adapt. Simple preventative measures like correcting posture, core strengthening exercises, and ergonomic furniture can deter bone spurs.

Genetic Predispositions and Bone Spurs

Hereditary Factors and Bone Spurs

- A family history of osteoarthritis elevates risks for bone spurs

- Gene mutations affecting cartilage formation increase susceptibility

Developmental Abnormalities and Joint Spurs

- Congenital hip dysplasia promotes early degeneration and spur growth

- Spinal abnormalities like scoliosis cause asymmetric disk loading

Other Contributing Genetic Factors

- Existing autoimmune disorders can accelerate joint damage

- Endocrine diseases like diabetes incline cartilage breakdown and spurs

Some genetic and congenital factors either initiate too much bone growth, cause premature joint degeneration, or otherwise disrupt normal skeletal development. While not necessarily the direct catalyst, inherited conditions can promote an environment conducive to bone spurs. Proper management of these disorders may help deter excessive bone formation.

Symptoms and Effects of Bone Spurs

Bone spurs can often develop without noticeable symptoms in the early formation stages. As they enlarge, surrounding nerves, tissues, and bones begin getting aggravated – provoking localized pain and inflammation.

Location-Specific Symptoms

The most common parts affected are the spine, heels, knees, shoulders, hips, elbows, and wrists. Symptoms manifest according to the area impacted.

Spinal Bone Spurs

- Neck pain, stiffness, muscle spasms

- Numbness/tingling in shoulders and arms

- Headaches associated with arthritis or disks

- Lower back – Sciatica pain down legs

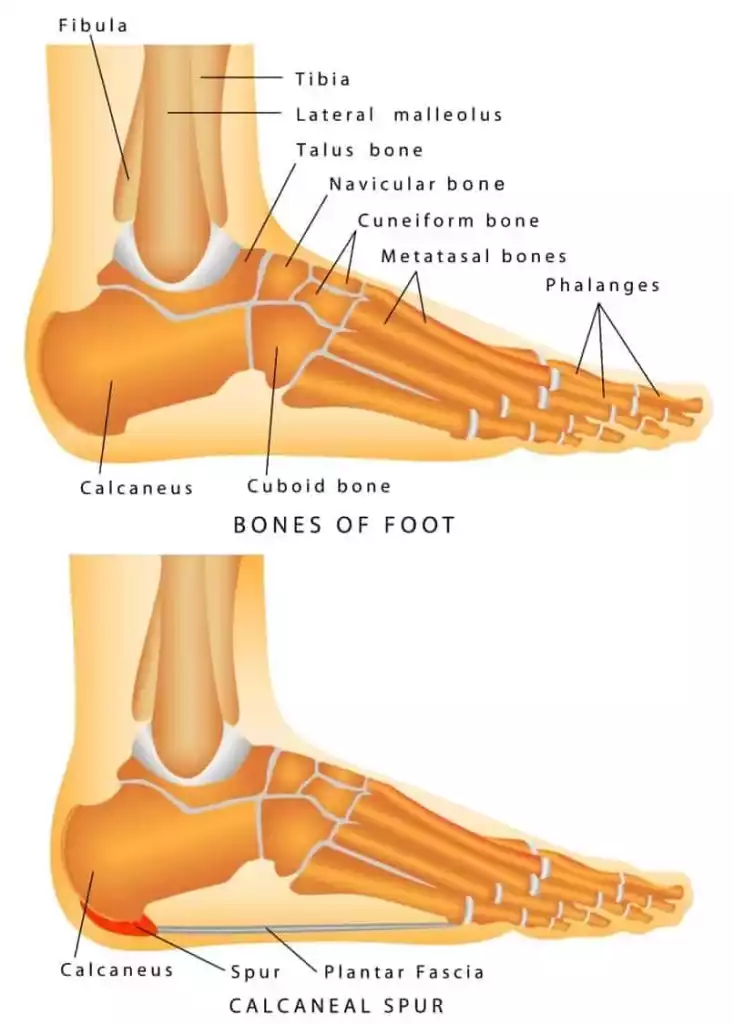

Heel Bone Spurs

- Intense localized pain when standing or walking

- Limping due to plantar fasciitis tearing

- Feet alternately red and numb from inflammation

Shoulder Bone Spurs

- Pain raising arms or reaching behind the back

- Difficulty lifting objects due to rotator cuff rubbing

- Sleep disruptions lying on the affected shoulder

Impact on Joint Function and Mobility

- As bone spurs enlarge, everyday movement becomes hampered depending on the location. Simple actions like walking, bending down, looking sideways, grasping objects, or getting dressed can provoke sudden pain in extreme joint positions.

- Cartilage damage from the underlying arthritis also worsens over time. This manifests into chronic stiffness and tightness, greatly restricting flexibility regardless of the spur sizes.

Potential Complications if Left Untreated

- Though small or asymptomatic spurs may not progress further, larger bone growths often exacerbate joint degeneration when ignored. Intensifying arthritis, ligament wear, cartilage loss, and irritation to surrounding structures can lead to significant disabilities.

- Eventually, the arthritis and bone/tissue damage can become severe enough to necessitate invasive joint replacement surgeries that could have been avoided with earlier treatment.

Identifying Common Symptoms

Some of the most characteristic bone spur signals regardless of the area impacted include:

Persistent Joint Pain and Stiffness

- Aggravated by movement at extremes of joint range

- Creeping stiffness even at rest as arthritis worsens

Limited Range of Motion

- Activities requiring twisting or bending feel restricted

- Spurs block joint mobility depending on the location

Swelling and Inflammation

- Fluid buildup, warmth, and tenderness around joint

- Redness may be present if bone spurs are large

Diagnosis of Bone Spurs

Doctors utilize a combination of medical history reviews, physical examinations, and imaging tests to confirm the presence and extent of bone spurs.

Diagnostic Tools and Procedures

Medical History Review

- Age, injury histories, and active lifestyle to gauge risks

- Joint-specific evaluations – pain triggers, stiffness, changes

- Helps determine if OA or acute injuries present

Physical Examination

- Palpate joint for swelling, warmth, limited mobility

- Assess range of motion and movements eliciting pain

- Identifies potential coexisting issues like tendinitis

Imaging Techniques

- X-rays best confirm bony growths and joint space narrowing

- MRI scans detail soft tissue damage, cartilage loss patterns

- CT scans are beneficial for complex anatomical areas like spine

- Ultrasounds occasionally used to supplement other imaging

These techniques combined establish bone spur properties like sizes, locations, arthritis progression, and other degenerative characteristics needed to guide optimal treatment.

Differential Diagnoses and Coexisting Conditions

Differentiating Bone Spurs from Arthritis

- Arthritis disturbs joint spaces and alters mobility

- Spurs show abnormal bone projections under imaging

Recognizing Secondary Symptoms

- Adjacent tendon inflammation (tendinitis) common

- Ligament tears and cartilage defects are also possible

Coexistence with Other Joint Disorders

- Bone spurs frequently appear with disc herniations

- Can accompany conditions like gout, synovitis, etc.

Doctors must exclude other diagnoses and identify if additional complications are involved with the bone spurs through comprehensive assessments. This prevents overlooking serious pathologies needing urgent care.

Treatment

Non-surgical Approaches

Non-surgical care aims to manage symptoms without surgery in patients unwilling or medically unfit for invasive procedures. They focus on pain relief, anti-inflammatories, physical therapy, and assistive devices.

Pain Management and Anti-inflammatory Medications

Oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen, naproxen, diclofenac, or aspirin provide analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects. They help ease soreness and swelling associated with bone spurs and related arthritis. These medications carry gastrointestinal and cardiovascular side effects with long-term use, so doctors monitor kidney/liver function.

Powerful steroid anti-inflammatories like cortisone may be injected directly into problematic joints every few months. They reduce inflammation irritation from bone spurs and cartilage loss extremely effectively but eventually degrade joint tissues further if over-used.

Physical Therapy and Exercise

Specific stretches and exercises improve flexibility, circulation, muscle strength, and range of motion. This protects the joint from disabling stiffening. Physical therapists identify problem areas needing targeting, progress difficulty gradually, and ensure optimal technique.

Low-impact cardio like swimming, biking, or incline walking avoids further damaging fragile joints. Yoga tailors pose to open up common bone spur locations like the back and shoulders. Massage loosens tense muscles around affected joints.

Assistive Devices and Orthotics

These aid physical functioning to prevent further joint damage. Devices like splints, braces, special shoe inserts, or heel cups help realign posture, absorb shocks, and shift pressures away from bone spurs. Canes and walkers assist with mobility issues from severe osteoarthritis fall risks. Cervical collars provide extra neck bone spur relief.

Minimally Invasive Procedures

These specialty injections, nerve ablations and sound wave therapies locally target bone spur irritation when medication and conservative therapy plateaus. They aim to avoid major surgery risks in elderly or chronically ill patients still needing significant symptom relief.

Corticosteroid Joint Injections

Injecting corticosteroid medication directly into the affected joint spaces bathes irritated nerves and tissues in potent anti-inflammatories. The steroids dramatically reduce localized swelling and discomfort from bone spurs and arthritis for months at a time. Risks include weakened cartilage and lightening skin pigmentation with repeated injections.

Radiofrequency Nerve Ablation

Heated radio wave currents apply to specific sensory nerves transmitting pain signals from bone spurs. This disrupts firing pathways to the brain, numbing irritation for many months. It cannot reverse joint damage or cure arthritis but buys time before surgery. Risks include nerve damage and increased inflammation temporarily.

Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy

Focused pulsating acoustic sound waves target the bone spur tissue and trigger resorption activity. This helps shrink the spur throughout treatments. It works best for mild heel and shoulder spurs. Risks include pain flaring and swelling initially before improvements. Ruptured blood vessels or nerve damage also occur rarely.

Surgical Interventions

If all other conservative and minimally invasive treatments fail and bone spurs with arthritis cause persistent disabilities, surgical removal becomes necessary. Surgeries aim to resect irritating spurs and repair extensively damaged joints.

Arthroscopic Surgery

This procedure utilizes miniature cameras and instruments inserted through tiny incisions. It allows surgeons to see inside joints and carefully target isolated areas of cartilage damage, inflamed tissue, and bone spurs under magnification for smoother removal.

Patients experience less bleeding, smaller scars, and faster recovery than traditional open surgery. However, arthroscopy cannot reverse significant arthritis progression seen in late-stage joint disorders.

Joint Resurfacing and Replacement

For those with severe, bone-on-bone arthritis and large osteophytes causing debilitating pain, joint replacement becomes essential. Damaged cartilage and ends of affected bones get surgically smoothed down and covered with smooth synthetic implants shaped like the original anatomy.

Resurfaced parts then attach to the preserved bones for seamless function. While a major undertaking, joint replacements provide long-term restoration of flexibility and strength if nonsurgical care no longer suffices.

Osteophytectomy and Bone Spur Removal

This open or arthroscopic procedure focuses just on trimming abnormal bone growths around affected joints, rather than complete resurfacing. It helps earlier-stage or localized bone spurs accompanied by cartilage thinning before requiring total joint replacements.

Surgeons strategically detach areas where spurs emerge from the bone and use surgical burrs to carefully contour and smooth affected regions without damaging key ligaments or structures. Patients receive hardware or casts to stabilize operated bones during post-surgical healing.

Preventing and Managing Bone Spurs

While heredity plays a role, implementing proactive lifestyle habits reduces unnecessary strain on joints vulnerable to bone spurs. Managing risks early on helps delay onset.

Lifestyle Changes and Prevention Tips

Maintaining a Healthy Weight

Excess body weight transfers abnormally high pressures onto joints like knees and hips during everyday activities. Just an extra 10-20 lbs applies exponentially more force accumulating over years. Keeping fit mitigates arthritis and cartilage thinning risks leading to bone spurs.

Proper Posture and Ergonomics

How people sit, stand, walk, and position limbs daily strains bones and muscles unevenly long-term if done improperly. Slouching crumples spinal disks. Looking down tenses neck vertebrae. Twisting awkwardly shifts the hip socket’s weight distribution.

Practicing mindful posture corrections and positions while working, driving, exercising, and sleeping distributes mechanical forces optimally across skeletal joints.

Regular Exercise and Stretching

While excessive high-impact exercise damages joints, practicing moderation keeps the body conditioned. Low-impact cardio improves circulation and flexibility. Stretching keeps muscles lengthened to prevent tugging extra at bone attachments.

Light resistance training strengthens supportive muscles around vulnerable joints for added stability. Yoga customizes poses for problem areas prone to bone spurs.

Ergonomics and Proper Body Mechanics

Workplace Adjustments

People in strenuous vocations using identical movements for hours daily are at risk of overtaxing the related joint complexes. Adjusting workstations, using mechanical aids for lifting/reaching, incorporating micro-breaks, and mixing up motions periodically save skeletal structures.

Sports and Fitness Practices

High-intensity athletes in sports like basketball, tennis, ballet, weightlifting, etc. endure asymmetrical stresses certain joints aren’t designed for long-term. Implementing balanced strength programs, massage, and rest days aids recovery from microdamage accumulation.

Choosing Appropriate Footwear

Wearing well-cushioned shoes matched to foot type and individual gait patterns helps absorb forces properly. Poor quality or worn-out shoe soles and heels transmit excess shock through feet, ankles, and knees exponentially adding up over the years.

Injury Prevention and Safe Physical Activities

Warm-up and Cool-down Techniques

- Prep work and progressions minimize tissue injuries

- Calibrates musculoskeletal structures for specific exertion

- Tapering loads after ensures gradual transitions

Avoiding Overuse and Repetitive Motion

- Periodizing activities and rotating muscle groups

- Giving tissues ample rest/recovery days in between

- Controlling speed, form, and exertion level

Protective Gear and Correct Body Mechanics

- Pads, braces, tape, etc. as needed for high-impact sports

- Following techniques and motions the limited joints unaided

Seeking Early Intervention and Treatment

Regular Health Check-ups

- Physicals establish health baselines identifying problems early

- Used to catch conditions causing abnormal joint structures

- Maintaining musculoskeletal wellness and screening for risks

Prompt Recognition of Symptoms

- Noting potential osteoarthritis indicators in joints

- Any unusual or progressive pain, stiffness, or swelling demands evaluation

Timely Consultation with Healthcare Professionals

- Rehab teams evaluate injuries requiring therapy courses optimally

- Specialists determine if bone spurs/arthritics require monitoring

- Clear intervention pathways either non-surgical or surgical

Summary

Bone spurs (osteophytes) are bony projections that form along joint edges often stemming from osteoarthritis cartilage damage or repetitive microtrauma over time. Spurs begin innocuously but enlarge progressively as the body tries stabilizing stressed joints unnaturally.

Eventually, they irritate surrounding nerves, restrict mobility, and contribute to degenerative joint changes. Heels, knees, shoulders, spine, and hands are frequently locations affected. Managing causative factors early through balanced strength training, workplace ergonomics, healthy nutrition, and lifestyle habits may help deter bone spurs.

Symptoms manifest depending on the locations affected but share general characteristics like localized soreness, swelling, tingling, stiffness, and loss of flexibility. Spurs can go unnoticed for years until aggravated through athletic overexertion or accidents straining the area. Diagnostic imaging scans X-rays, MRIs, and CTs to detail bone spur shapes, sizes, arthritis progression, and complications guiding treatment.

Conservative treatment focuses on pain relief, anti-inflammatories, targeted stretching and exercises, custom shoe orthotics/braces, and activity modification. Interventional options for recalcitrant cases include corticosteroid injections, nerve ablations using heat/cold energy, and sound wave therapy to break down tissues. Surgical removal becomes necessary for extensive spurs and irreparable arthritis that fails to respond to nonsurgical care.

Prevention through safe biomechanics, low-impact exercise, frequent posture corrections, and maintaining strength balances joint loads minimizing risks of bone spurs and osteoarthritis long-term.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Are bone spurs always associated with pain?

Not always. Small bone spurs may not be painful initially when they start to form. Many are found incidentally on imaging tests done to evaluate other joint issues. However, as bone spur formation continues over time, they become more likely to cause irritation symptoms. Over 90% of symptomatic bone spurs generate some degree of joint pain and inflammation.

Can bone spurs go away on their own?

Unfortunately, once bone spurs grow beyond a minor size, natural bone resorption processes in the body cannot remove them completely. While it is possible for symptoms of very small bone spurs to sometimes improve through nonsurgical treatments, the bony projections themselves typically do not go away without surgical removal.

Is surgery the only treatment option for bone spurs?

For bone spurs causing severe loss of mobility or function, surgery by an orthopedic specialist may be the most definitive option. However, various non-operative treatments can still help manage pain from bone spurs effectively, especially smaller ones. Approaches like steroid injections, physical therapy programs, radiofrequency nerve ablation, and extracorporeal shock wave therapy reduce bone spur irritation for many patients. Surgery is often a last resort if simpler therapies fail to provide adequate relief after sufficient courses.

How long does the recovery process take after bone spur removal?

The initial healing phase protecting operated bones and tissues requires strictly limiting weight bearing and motion for around 6 weeks. Light activity may resume gradually after, but it can take a full 3 to 6 months for pains, strength, coordination, and mobility to fully stabilize and improve following surgery depending on patient factors. Proper post-op rehabilitation therapy ensures patients regain as much flexibility and joint function as possible.

Can bone spurs recur after treatment?

Recurrence is possible if the factors promoting the original bone spur formation like osteoarthritis, repetitive overuse through occupational or athletic activities, lack of muscle support around the joint, and obesity issues continue unchecked without lifestyle changes. Some hereditary conditions also predispose toward recurrent bone spurs and accelerated joint degeneration. Maintaining a healthy weight, strong muscles, proper joint alignment and mechanics, and modifying activities helps prevent recurrence.

References

- Bone spurs – Symptoms and causes – Mayo Clinic. (2022, September 13). Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/bone-spurs/symptoms-causes/syc-20370212

- Bone Spurs. (2017, January 24). WebMD. https://www.webmd.com/pain-management/what-are-bone-spurs

- Veazey, K. (2022, October 31). What are bone spurs? https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/what-are-bone-spurs

- Eustice, C. (2020, January 4). What Is a Bone Spur? Verywell Health. https://www.verywellhealth.com/what-is-a-bone-spur-2552215

- Roland, J. (2017, April 26). Bone Spurs: What You Should Know About Osteophytosis. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/bone-spurs-osteophytosis#diagnosis