Developmental Delay

What is developmental delay?

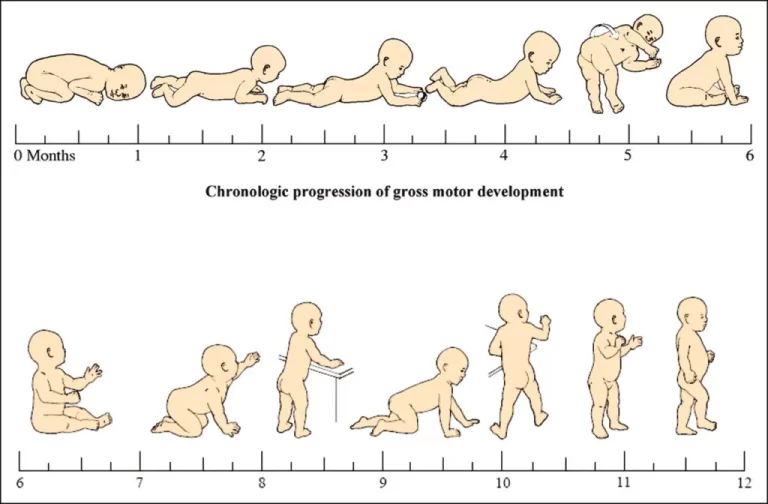

Developmental delay refers to a situation where a child does not reach their expected developmental milestones within the typical age range. These milestones encompass a variety of tasks that most children commonly acquire as they grow, including skills such as head control, rolling, crawling, walking, and talking.

Child development is a complex process involving the gradual attainment of these developmental milestones. When a child experiences abnormal delays in reaching these milestones, it is termed a developmental delay. Such delays can impact various aspects of a child’s development, including motor skills, speech and language abilities, as well as social skills. In cases where a child exhibits delays across multiple areas, it is referred to as a global developmental delay.

It’s important to note that children progress through these milestones in an ordered sequence over time. As each child is unique and develops at their own pace, diagnosing developmental delay can be challenging unless a child’s development significantly lags behind their expected level.

Physiotherapy plays a crucial role in addressing motor developmental milestones such as rolling, sitting, crawling, and walking, as well as enhancing physical development in terms of balance, coordination, and mobility. Additionally, physiotherapy focuses on promoting proper positioning and offers engaging exercises to improve postural stability and coordination. The ultimate goal of physiotherapy is to support children in achieving their developmental milestones as swiftly as possible.

Introduction

Human development encompasses a dynamic process involving physical, cognitive, and psychosocial changes that occur across the lifespan. These developmental trajectories often progress sequentially and independently while also influencing one another. Some notable developmental lines include:

- Physiologic Development and Homeostasis

- Structural and Anatomic Development

- Motor Development (both fine & gross motor aptitudes)

- Language Development (encompassing gesture and speech)

- Cognitive Development

- Personality Development

- Social Development

- Psychological Development

- Sexual Development

- Development of Adaptive Skills (Activities of Daily Living – ADL)

The development of the fetal brain initiates during the first trimester, specifically around the fourth week of gestation, and continues throughout pregnancy. This process entails rapid growth during early childhood, remaining active through adolescence and well into the third decade of life, with ongoing development across the lifespan.

Developmental delay is typically identified when a child fails to achieve developmental milestones compared to their peers within the same population. The extent of the delay is often classified using statistical criteria, categorizing it as mild (functional age <33% below chronological age), moderate (functional age 34% to 66% of chronological age), or severe (functional age <66% of chronological age). It’s important to note that “developmental delay” is a broad term that necessitates further specification, focusing on the particular facets of disrupted development.

It is not a standalone diagnosis but rather a descriptive term employed in clinical contexts. Furthermore, the terminology used to define developmental delay can vary by region or country. For instance, the UK uses “learning disability,” while the US employs “Intellectual Disability” to describe a group of individuals exhibiting significant delay, defined as “performance equal to or greater than two standard deviations below the mean on age-appropriate standardized norm-referenced testing” (IQ testing).

Developmental delay can be categorized into three types based on the number of domains affected:

- Isolated Developmental Delay: Involves a single developmental domain.

- Multiple Developmental Delays: Affects two or more domains or developmental lines.

- Global Developmental Delay (GDD): Characterized by a substantial delay across most developmental domains.

There are also other conditions with abnormal developmental patterns, such as:

- Intellectual Disability (ID): A developmental disability primarily impacting cognitive functioning. According to the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (ID), it is characterized by significant lifelong developmental deficits in learning, problem-solving, adaptive skill development, and independence, typically with onset before the age of 18.

- Developmental Disorders: A diverse group of syndromes marked by disruptions in typical developmental sequences or patterns, involving delays in developmental milestones and deviations in developmental processes. Despite the American Academy of Pediatrics’ emphasis on early screening, a considerable number of developmental disorders remain undiagnosed and untreated.

Types of Developmental Delays in Children

Developmental delays in children encompass a range of challenges that can affect their growth and development. Here are some key types of developmental delays:

Cognitive Delays:

Cognitive delays impact a child’s intellectual functioning and can lead to learning difficulties, often becoming apparent during school years. These delays may also affect a child’s ability to communicate and engage in play. Causes can include brain injuries due to infections like meningitis, shaken baby syndrome, seizure disorders, or genetic conditions such as Down syndrome.

Motor Delays:

Motor delays hinder a child’s coordination of both large muscle groups (gross motor skills) and smaller muscles (fine motor skills). Infants with gross motor delays may struggle with rolling over or crawling, while older children may appear clumsy or face challenges with activities like climbing stairs. Genetic conditions, muscular disorders like cerebral palsy or muscular dystrophy, and structural issues can contribute to motor delays.

Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Delays:

Children with developmental delays, including conditions like autism spectrum disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), often experience social, emotional, or behavioral delays due to differences in brain development. These delays can affect a child’s learning, communication, and interactions. Children may struggle with social cues, initiating communication, coping with frustration, and adapting to changes in their environment.

Speech Delays:

Speech delays can manifest as receptive language disorders (difficulty understanding words or concepts) or expressive language disorders (limited vocabulary and complex sentences for their age). Some children may have oral motor problems that impede speech production. Speech delays can result from various causes, including physiological factors like brain damage or hearing loss, genetic syndromes, environmental factors, or unknown origins.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD):

ASD encompasses a group of neurodevelopmental conditions characterized by unique thinking patterns, movement behaviors, communication styles, and sensory processing compared to neurotypical individuals. It is typically diagnosed in early childhood and may involve delayed language and social development. Symptoms vary but often include a lack of responsiveness to their name, aversion to physical affection, limited facial expressions, speech difficulties, repetitive behaviors, and a preference for routines. Early screening and intervention are essential in managing ASD, as there is no cure, but therapies and strategies can help individuals improve communication and daily functioning.

Each child is unique, and the specific challenges they face within these developmental delay categories can vary widely. Early identification and appropriate intervention are crucial in supporting children with developmental delays to reach their full potential.

Causes of Developmental Delays

The causes of developmental delays are complex and often multifactorial. In many cases, the precise cause remains unknown (idiopathic). However, when known, the etiology can typically be attributed to a combination of genetic, environmental, and psychosocial factors.

Genetic Factors:

While there isn’t a specific genetic substrate for developmental delay itself, developmental patterns often exhibit familial tendencies, such as late walking and talking. Nevertheless, some developmental delays may also signify risks for syndromes or developmental disorders. Genetic factors encompass a wide range of variations, from copy number variants (CNVs) to insertions, deletions, and duplications.

Fragile X syndrome, a trinucleotide repeat disorder involving the Fragile Mental Retardation 1 (FMR1) gene on the X-chromosome, is one of the most common known genetic factors associated with intellectual disability (ID). Fragile X syndrome also appears to increase the risk of autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

Imprinting disorders like Prader-Willi and Angelman syndromes, linked to paternal and maternal loss of function on chromosome 15q, respectively, can lead to developmental delay and distinct physical features. Additionally, developmental delay and specific phenotypes can be linked to conditions involving extra or altered chromosomes, such as Down syndrome (trisomy 21), Edwards syndrome (trisomy 18), and Patau syndrome (trisomy 13). X-linked disorders like Coffin-Lowry syndrome (predominantly in males) and Rett syndrome (in females) also contribute to developmental delays.

Environmental Factors:

A myriad of environmental factors can contribute to developmental delays and subsequent developmental disorders, affecting various stages of development:

Antenatal Factors

- Heritable disorders like Fragile X syndrome, Down syndrome, or chromosomal microdeletions and duplications.

- Maternal infections (e.g., rubella, cytomegalovirus, toxoplasmosis).

- Late maternal infections (e.g., varicella, HIV, malaria).

- Factors like being a first-time mother (primigravida), short inter-pregnancy intervals, and teenage pregnancy.

- Vascular issues, including hemorrhage and occlusion.

- Use of certain prescribed medications, such as antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) and cytotoxic drugs.

- Exposure to teratogens and toxins like smoking, alcohol, and opioids.

- Socioeconomic factors, including poverty.

Perinatal Factors

- Conditions like intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), prematurity, and periventricular leukomalacia.

- Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) and perinatal asphyxia.

- Metabolic issues such as hypoglycemia and bilirubin-related neurotoxicity.

- Socioeconomic disparities, including poverty.

Postnatal Factors

- Metabolic disorders like hypoglycemia, hyponatremia, or hypovolemia.

- Inborn errors of metabolism like phenylketonuria (PKU).

- Exposure to teratogens and toxins such as lead, arsenic, and mercury.

- Traumatic head injuries.

- Infections like neonatal meningitis and encephalitis.

- Maternal stress, including conditions like depression and anxiety.

- Understanding of maltreatment, intimate partner violence (IPV), or household roughness.

- Socioeconomic challenges, including poverty.

- Malnutrition, particularly deficiencies in essential vitamins and minerals like iron, folate, Vitamin D, and calcium.

The interplay of genetic, environmental, and psychosocial factors underscores the complexity of developmental delays. Identifying and addressing these factors are essential steps toward effectively supporting children with developmental delays and optimizing their developmental outcomes.

Epidemiology of Developmental Delays

The prevalence and distribution of developmental delays worldwide is a significant concern, with particular challenges in low and middle-income countries (LMICs). Here’s an overview of the epidemiological data related to developmental delays:

- Global Perspective: In 2016, it was estimated that approximately 52.9 million children globally experienced identifiable developmental delays. Given that 95% of the world’s population resides in LMICs, there is an elevated risk of developmental delays and disorders in these regions. The precise prevalence of developmental delays remains unclear; however, the World Health Organization (WHO) reports that about 10% of each country’s population has some form of disability.

- United States: In the United States, around 15% of children have been reported to have at least one developmental problem. This includes a range of developmental issues across cognitive, speech-language, and other domains.

- England: In England, the prevalence of intellectual disability (ID) in children under the age of five is approximately 2.7%, while among adults, it is approximately 2.17%. Global developmental delay (GDD) affects about 1% to 3% of school-age children or younger. Autism, a specific developmental disorder, has a prevalence of approximately 2.5%.

- Specific Domain Prevalence: The prevalence of developmental delays varies across different domains, with some notable figures based on data from various sources:

- Cognitive Delay: Estimated to affect around 1% to 1.5% of the population.

- Learning Disabilities: Affecting approximately 8% of individuals.

- Speech and Language Delays: This domain exhibits significant variability, with prevalence ranging from 2% to as high as 19%.

- Overall Developmental Delays: Approximately 15% of children experience some form of developmental delay across various domains.

- Gender Differences: Research, such as the Drakenstein Child Health Study in Western Cape, South Africa, has noted a higher risk of low developmental performance in boys in high-risk environments. Several other studies have also reported a slightly increased incidence of developmental delays in males, which could be attributed to genetic variability on the X chromosome.

Understanding the epidemiology of developmental delays is essential for policymakers, healthcare providers, and researchers to develop effective strategies for early detection, intervention, and support. It also highlights the need for global efforts to address these challenges, particularly in resource-constrained settings.

Pathophysiology of Developmental Delays

Developmental delays, in the majority of cases, are considered idiopathic, meaning their precise underlying pathophysiology is unknown. However, research and epidemiological studies have proposed several mechanisms that may contribute to the development of developmental delays and disabilities. While some forms of developmental delay have clear genetic etiologies, many others remain poorly understood.

Genetic Factors:

Genes are believed to play a significant role in developmental delays, especially considering that some forms of developmental delay tend to run in families. While specific genetic causes are known for conditions like Fragile X syndrome or Down syndrome, the genetic underpinnings of most developmental delays are still unclear. For conditions like autism spectrum disorder (ASD), there are over 100 identified risk alleles, reflecting the genetic complexity of these disorders.

Environmental Factors:

Environmental factors can also influence the pathophysiology of developmental delays. Perinatal complications, maternal stress during pregnancy, maternal immune activation (MIA), and socioeconomic factors like poverty can all impact fetal brain development. However, establishing direct cause-and-effect relationships for most developmental disorders remains challenging.

Hypothalamic-Pituitary Axis (HPA):

The hypothalamic-pituitary axis (HPA) plays a crucial role in regulating the body’s stress response. Psychosocial stressors experienced by pregnant women, MIA, and alterations in the functioning of the HPA can potentially affect fetal brain development. However, specific causal links between these factors and developmental delays are not well-defined.

Differential Susceptibility:

The concept of “differential susceptibility” proposed by researchers like Boyce suggests that various factors can create a biological vulnerability to environmental stressors, but this vulnerability is only expressed when these stressors are present. In other words, not all individuals with a biological predisposition to developmental anomalies will necessarily experience them unless exposed to specific environmental stressors. Moreover, even children with this vulnerability can thrive if they are in highly favorable and nurturing environments that foster resilience.

Overall, the pathophysiology of developmental delays is complex and multifactorial, involving a dynamic interplay between genetic, environmental, and psychosocial factors. While some specific causes are well-established, many aspects of these disorders remain the subject of ongoing research and exploration. Understanding these factors is crucial for developing effective interventions and support for individuals with developmental delays.

Identifying Developmental Delay in Children

Recognizing developmental delays in children is crucial for early intervention and support. Children may be considered developmentally delayed in various domains, and specific milestones can help assess their progress. Here’s how developmental delay is identified in different areas:

Gross Motor Skills:

- Lack of neck/head control by 6 months

- Inability to sit independently by 8 months

- Failure to get to a sitting position by 10 months

- No crawling or bottom shuffling by 12 months

- Absence of independent walking by 18 months

Fine Motor Skills:

- Inability to bring fingers to the mouth for 6 months

- Difficulty moving an object from one hand to another by 8 months

- Unable to pick up a small object with three fingers by 10 months

- Struggling to pick up an object using two fingers and thumb for 14 months

- Unable to put an object inside a cup for 15 months

Speech and Communication:

- Lack of babbling by the age of 15 months

- Absence of single words spoken by the age of 2 years

- Incapability to speak in brief corrections by the age of 3 years

- Poor pronunciation or articulation

- Difficulty forming sentences

Cognition/Mental Capacity:

- Slow learning of basic skills like feeding, dressing, or toilet training

- Delayed speech or difficulty in verbal communication

- Inability to connect actions with consequences

- Difficulty remembering things

- Struggles with problem-solving or logical thinking

Social Development:

- A lack of enjoyment in playing with caregivers and limited communication through facial expressions and body language by around 3 months

- Failure to respond to their name by the age of approximately 7 months

- An inability to distinguish between strangers and familiar individuals by the age of about 12 months

- A lack of imitation of others’ behavior by around 2 years

- Limited interest in the company of other children and reluctance to engage in play with them by the age of 2 years or older

Identifying these developmental delays in children is essential for timely intervention and support, which can significantly improve their developmental outcomes. It’s important for parents, caregivers, and healthcare professionals to monitor a child’s progress and seek assistance if any delays are observed. Early intervention can make a significant difference in a child’s development and future well-being.

History and Physical Examination in Children with Developmental Delays

A comprehensive assessment of children with developmental delays is crucial for accurate diagnosis and intervention. This evaluation encompasses a thorough history-taking, physical examination, and, when necessary, laboratory workup. Here is a detailed breakdown:

History:

- Developmental Timeline: Gather comprehensive data on the child’s development from conception to their current age, focusing on key milestones and areas of delay.

- Family History: Construct a detailed family pedigree, spanning first, second, and third-degree relatives, as familial patterns can provide valuable insights.

- Narrative of Delays: Document the presentation and course of the developmental delays, paying attention to any regression or loss of acquired skills.

- Medical Records: Review prenatal, perinatal/birth, and postnatal records, including neonatal history for adverse events like hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) or jaundice.

- Developmental Milestones: Chart each developmental line, listing milestones related to motor skills, social interaction, language, learning, etc.

- Immunization and Nutritional History: Obtain information regarding immunizations and the child’s feeding and eating habits.

- Medical History: Collect details about hospitalizations, surgeries, accidents, injuries, and medications.

- School and Social Performance: Document the child’s performance in school, including any academic or social challenges.

Physical Examination:

- Growth Parameters: Measure occipitofrontal circumference, weight, height, and calculate BMI to assess growth.

- Comprehensive Physical Examination: Conduct a head-to-toe assessment to identify any dysmorphic features or physical abnormalities.

- Neurologic Evaluation: Include assessments of hearing and vision, as well as a detailed neurologic examination.

- Dysmorphology: Carefully examine for any physical features that may indicate an underlying genetic syndrome or disorder.

Evaluation:

Assessing developmental delays often requires a multidisciplinary approach involving experts in various fields, including primary care providers, pediatric subspecialists (e.g., neurologists, child and adolescent psychiatrists, developmental and behavioral pediatricians), and other professionals such as psychologists, geneticists, speech and language pathologists, occupational therapists, and nutritionists. This collaborative effort is essential to provide a comprehensive evaluation.

Developmental Screening:

Routine developmental screening should be a part of well-child visits and may be triggered by parental concerns or clinician observations. Developmental screening should occur at 9, 18, and 30 months of age, with autism-specific screening recommended at 18 and 24 months. Validated screening instruments like the Ages and Stages Questionnaire, Third Edition (ASQ-3), and the Parents’ Evaluation of Developmental Status (PEDS) can aid in early detection. These tools help identify potential developmental delays and determine the need for further assessment.

Laboratory Workup:

Laboratory tests should be judiciously chosen based on clinical indications. Given that most developmental delays are idiopathic, significant or pathognomonic findings in laboratory testing are rare. Common laboratory evaluations include:

- Blood tests (complete blood count, electrolytes, lead screening, lipid panel, metabolic chemistry panel, iron, calcium, phosphate, creatinine kinase, uric acid, thyroid function tests, lactic acid, etc.).

- Urine tests (routine urinalysis, organic acids, amino acids, etc.).

- Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis is rarely indicated for developmental assessment, except in specific situations.

- Genetic testing, including chromosomal microarray (CMA) and Fragile X screening, may be considered based on clinical findings and indications. Referral to a geneticist may be necessary for further evaluation.

Additional Assessments:

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain is rarely indicated in routine assessment unless specific clinical findings or indications are present.

- Electroencephalography (EEG) may be useful if there is a history of regression or observed seizure activity.

A comprehensive assessment of developmental delays in children involves a meticulous history-taking, thorough physical examination, and selective laboratory workup. Collaboration among healthcare providers and experts is crucial for accurate diagnosis and timely intervention, ensuring that children with developmental delays receive appropriate care and support.

Differential Diagnosis for Developmental Delay in Children

Developmental delay in children is often a complex issue with various potential underlying causes. While most cases are idiopathic and transient, some may progress to specific developmental disorders or conditions. Here is a differential diagnosis of developmental delay milestones and associated risks:

- Intellectual Disability (ID):

- General developmental delay (GDD)

- Fragile X syndrome

- Failure to thrive (FTT)

- Anemia

- Thyroid deficiency

- Social deprivation

- Delayed Speech and Language:

- General speech delay

- Developmental language disorder

- Intellectual disability (ID)

- Autism spectrum disorder (ASD)

- Social communication disorder

- Developmental language disorder

- Social deprivation

- Sensory Impairment:

- Developmental hearing disorder

- Deafness

- Developmental vision disorder

- Blindness

- Poor visual acuity

- Behavior Problems:

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD)

- Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD)

- Autism spectrum disorder (ASD)

- Childhood-onset schizophrenia

- Mood/Affect Regulation:

- Autism spectrum disorder

- Intellectual disability

- Mood disorders

- Childhood-onset schizophrenia

- Learning Problems:

- Intellectual disability (ID)

- Sensory deficits (hearing or vision)

- Dyslexia

- Autism spectrum disorder (ASD)

- Movement Disorders:

- Epilepsy

- Tourette syndrome

- Chronic tic disorder

- Motor Delays:

- Cerebral palsy

- Muscular dystrophy

- Spinal muscular atrophy

- Epilepsy

- Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE)

- Intellectual disability

- Autism spectrum disorder (ASD)

Treatment of Developmental Delay in Children

The management of developmental delay in children is a collaborative effort involving various healthcare providers and specialists. Treatment strategies are typically multi-modal and aim to address the specific needs of each child. Here is an overview of the key components of treatment and management:

Team Approach:

Treatment for developmental delay often requires a multidisciplinary team. Primary care providers play a central role, collaborating with pediatric subspecialists such as neurologists, child and adolescent psychiatrists, developmental and behavioral pediatricians, and other experts like psychologists, geneticists, speech and language pathologists, occupational therapists, physical therapists, and nutritionists as needed.

Therapeutic Partnership:

The lead member of the healthcare team, usually the primary care provider, establishes a therapeutic partnership with parents and families. They provide comprehensive information about the developmental delay, including its course, diagnosis, prognosis, and potential complications. Psychosocial support and counseling for parents are integral parts of care, and information should be conveyed at a level that parents can understand to enhance acceptance and adherence to care plans.

Social Work Support:

Some families may require social work support services for coordination, transportation, home visits, and other essential evaluations. In cases where parents may not fully comprehend the nature of the developmental delay or are in denial, follow-up appointments with the primary care provider can be beneficial.

Early Interventions:

Early interventions are crucial in addressing developmental delays. These may include:

- Early Childhood Education: Enrolling the child in appropriate early childhood education programs.

- Early Intervention Programs: Participating in specialized early intervention programs tailored to the child’s needs.

- Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT): Ensuring children receive comprehensive healthcare services, including developmental screenings and assessments.

- Parenting Support: Offering parent training, which may involve parent-child interaction therapy (PCIT) with phases like parent-directed interaction (PDI) and child-directed interaction (CDI). Parents may also receive guidance on creating stimulating environments at home, school, and daycare.

Referrals:

Depending on the specific challenges and needs of the child, referrals to various specialists and services may be necessary. These include:

- Behavior Problems: Referral to a child and adolescent psychiatrist and/or behavior therapist (Board-Certified Behavior Analyst – BCBA).

- Social Skills Problems: Consider referral for social skills training, both individual and group.

- Auditory Impairment: Referral to audiology for assessment and support.

- Visual Impairment: Referral to an ophthalmologist for evaluation and intervention.

- Gross/Fine Motor Delay: Regarding referral to physiotherapy and occupational therapy.

- Speech & Language Delay: Referral to a speech and language pathologist for evaluation and therapy.

Community-Based Services:

Multiple children with developmental delays are suitable for community-based services. Primary care providers should be knowledgeable about these services, eligibility criteria, and the process for making referrals. Some of these services may include:

- Head Start: Early childhood education programs.

- Special Education: Utilizing Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) or 504 Plans to tailor education to the child’s needs.

- Other Community Service Agencies: Exploring additional community programs and resources to support the child’s development.

The management of developmental delay in children requires a holistic and collaborative approach. By engaging a multidisciplinary team, providing early interventions, offering parental support, and making appropriate referrals, healthcare providers can help children with developmental delays achieve their fullest potential and improve their quality of life.

Physiotherapy for Developmental Delay in Children

Early intervention through physiotherapy is crucial for children with developmental delays. Physiotherapy can aid in enhancing a child’s physical abilities, improve their overall mobility, and support them in achieving developmental milestones. Here is an overview of physiotherapy treatment for developmental delay:

- Benefits of Early Intervention: Commencing physiotherapy at an early age is highly advantageous because a child’s brain is more adaptable, making them more responsive to treatment. Physiotherapy can effectively help children learn essential everyday tasks, enhance their balance, refine walking skills, improve handwriting, and engage in general physical activities.

- Focus of Physiotherapy Treatment: Physiotherapy treatment for developmental delay is tailored to address specific goals, including:

- Increasing muscle strength

- Stretching stiff joints

- Enhancing balance and coordination

- Promoting normal movement patterns

- Achieving developmental milestones

- Maximizing a child’s potential

- Improving the overall quality of life

- Fostering independence in daily tasks

- Treatment Methods: Physiotherapy involves various techniques and exercises, such as:

- Muscle-strengthening exercises to improve weight shifting and balance

- Mobility exercises to facilitate walking and daily activities

- Hand exercises to enhance fine motor skills for writing and object manipulation

- Mirror imaging exercises to increase limb awareness during rest and movement (proprioception)

- Muscle stretching to lengthen muscles, reduce contractures, and improve range of motion

- Correcting and varying positioning to enhance head and trunk control, coordination, and balance

- Quality of movement exercises and teaching new movement patterns

- Guidance on using supportive devices like wheelchairs or orthotic devices if necessary

- Hydrotherapy to relax stiff muscles and joints and maximize mobility in a water-based environment

- Tailored Treatment: Physiotherapists recognize that each child with developmental delay has unique challenges. Therefore, treatment is individualized to meet the specific needs of the child.

- Stimulating Environment: Physiotherapy treatment is conducted in a stimulating and safe environment that combines fun and effective exercises to engage the child. The goal is to motivate them to explore and interact with their surroundings.

- Achieving Maximum Potential: The ultimate aim of physiotherapy is to help children with developmental delays reach their full potential and gain independence in their daily lives.

Physiotherapy plays a crucial part in sustaining children with developmental delays. Through early intervention and personalized treatment, physiotherapists can assist children in achieving their developmental milestones, enhancing their mobility, and improving their overall quality of life.

Prognosis of Developmental Delay in Children

The prognosis for developmental delay in children is generally positive since many cases tend to resolve spontaneously. However, it’s essential to closely monitor each case until resolution or until it progresses to a neurodevelopmental disorder or syndrome. Several factors can influence the prognosis, including both positive and negative prognostic indicators.

Positive Prognostic Factors:

- Maternal education: Higher levels of maternal education are associated with better developmental outcomes in children.

- Access to basic life and health resources: Adequate access to essential resources can contribute to improved developmental outcomes.

- Older child age: Children who are slightly older may catch up with developmental milestones over time.

Negative Prognostic Factors:

- Lack of parental education: Limited parental education can negatively impact a child’s developmental progress.

- Anemia during pregnancy: Maternal anemia during pregnancy is a risk factor for poor developmental outcomes.

- Malnutrition: Inadequate nutrition during pregnancy or early childhood can hinder development.

- Premature birth: Premature babies are at higher risk of developmental delay.

- Male gender: Boys may be more prone to developmental delays.

- Low birth weight (LBW): LBW infants may face developmental challenges.

- Prenatal and postnatal depression: Maternal mental health can influence a child’s development.

- Intimate partner violence (IPV): Disclosure of intimate partner violence can have an adverse impact on the development of a child.

- Substance use during pregnancy: The use of drugs, tobacco, or alcohol during pregnancy can harm fetal development.

- Poverty: Economic hardship can contribute to developmental delays.

Additionally, certain warning signs should be addressed promptly to prevent significant developmental deficits. These warning signs include hearing or vision loss at any age, loss of previously acquired developmental skills, persistent issues like hypotonia or hypertonia, asymmetrical movements, absence of communicative speech at 16 months, & 7 unnecessary head circumference (either > 99.6 percentile/< 0.4 percentile).

Prevention and Patient Education for Developmental Delays in Children

Preventing and minimizing developmental delays in children involves creating environments that support cognitive, motor, sensory, psychological, social, and emotional development across various settings, such as home, school, and daycare. Parent education and guidance play a crucial role in achieving these goals. Here are some key points for patient education and deterrence:

- Early Parent Training: Parent training programs can help parents understand the functional impact of their child’s needs and the potential risks associated with developmental delay. These programs should be integrated into prenatal and well-child visits to provide parents with essential knowledge and skills.

- Caregiver Skills Training (CST): Programs like CST, developed by the World Health Organization (WHO), can be valuable for families with children facing developmental delays or disorders. CST covers several modules, including engagement, communication, behavior management, play, adaptive behavior, caregiver self-care, and continuing practice.

- Community Support: Communities should offer a supportive environment for parents and children. This includes ensuring physical safety, providing sanitary facilities, access to safe drinking water, adequate nutrition, and essential prenatal and postnatal care for women, including maternity leave. Well-childcare services should be available to all children, and early childhood education should be promoted.

- Universal Pre-school: Encouraging universal access to preschool education can have a positive impact on children’s development, helping them acquire important skills before starting formal schooling.

- High-Quality Education: Ensuring access to high-quality education throughout a child’s academic journey is crucial. Quality education supports intellectual, social, and emotional growth.

- Developmental Guidance and Support: Universal developmental guidance and support services can help parents navigate the challenges of child-rearing. These services should be readily available to assist parents in understanding and addressing their child’s developmental needs.

- Encourage Open Communication: Clinicians should encourage parents to voice their concerns and questions regarding their child’s development. Taking parental comments and concerns seriously is essential for early detection and intervention.

Improving Healthcare Team Outcomes for Child Development

Enhancing the developmental outcomes of children is a collective responsibility that involves a coordinated effort from healthcare providers, parents, and society as a whole. To achieve this, it’s essential to implement systematic examination and developmental monitoring for all children. Unfortunately, even in developed countries like the USA, there’s a significant gap in providing adequate parent-completed developmental screening. Here are some key considerations for improving healthcare team outcomes:

- Universal Developmental Monitoring: Healthcare providers should prioritize universal developmental monitoring for all children during routine healthcare visits. This includes the systematic use of parent-completed developmental screening instruments to assess behavior, interaction, and developmental milestones.

- Healthcare Provider Training: Healthcare professionals should receive training on the importance of developmental monitoring, early detection of delays, and appropriate interventions. This training ensures that healthcare teams can effectively identify and support children with developmental concerns.

- Parent Education: Parents should be educated about the significance of developmental monitoring and encouraged to actively participate in the process. Healthcare providers can provide information on developmental milestones, warning signs, and the importance of timely interventions.

- Collaboration: Collaboration between healthcare providers, parents, and relevant support services is essential. Healthcare teams should work closely with parents to address concerns, provide guidance, and facilitate referrals to specialists when needed.

- Accessible Services: Ensure that developmental evaluation and support services are readily accessible to all children, including those in low and middle-income countries (LMIC). This may involve expanding healthcare infrastructure and services in underserved areas.

- Telehealth Options: Explore telehealth options to reach children in remote or underserved areas, allowing them to access developmental monitoring and support services.

- Public Awareness: Promote public awareness campaigns to highlight the importance of early developmental monitoring and intervention. Educating society about the long-term benefits of identifying and addressing developmental delays can lead to more favorable outcomes.

- Research and Data: Continuously collect data and conduct research to assess the effectiveness of developmental monitoring programs and identify areas for improvement.

Living with Developmental Delay

Children with developmental delays, like all children, have a capacity for learning and growth. However, their learning process may differ, characterized by slower progress and alternative learning pathways. Understanding these nuances is crucial for effective early intervention. Here are key insights into living with developmental delay and the implications for early intervention:

- Slower Skill Development: Children with developmental delays often require more time to acquire new skills. They may learn at a slower pace compared to their peers. Early intervention should account for this extended learning curve.

- Step-by-Step Learning: To facilitate skill development, children with developmental delays may benefit from breaking down complex tasks into smaller, more manageable steps. Providing structured, step-by-step guidance can aid their learning process.

- Difficulty in Skill Transfer: These children may face challenges when transferring skills learned in one environment to another. Early intervention strategies should focus on fostering skill generalization across different settings and contexts.

- Increased Practice Opportunities: Offering ample opportunities for practice is essential. Children with developmental delays may need more repetitions and varied practice scenarios to master skills effectively.

- Multidisciplinary Support: Early intervention typically involves collaboration among various professionals. The following experts may be part of the support and intervention team:

- General Practitioner (G.P)

- Child and Family Health Nurse

- Paediatrician

- Audiologists and Deaf Advisors

- Occupational Therapists

- Speech Pathologists

- Psychologists

- Psychiatrists

- Social Workers

- Therapists (e.g., speech-language, physio)

- Special Education Teachers and Support Workers

- Kaitakawaenga (Maori Cultural Advisors)

- Cultural Sensitivity: Cultural advisors, such as Kaitakawaenga, play a vital role in ensuring cultural sensitivity and appropriateness in intervention strategies, respecting the unique cultural backgrounds of children and their families.

Developmental Delay vs. Autism: Key Distinctions

Distinguishing between developmental delay and developmental disabilities, like autism spectrum disorder (ASD), is crucial for understanding your child’s needs and providing appropriate support. Here’s a breakdown of these differences:

Developmental Delay:

A developmental delay occurs when a child doesn’t reach developmental milestones at the expected times. This means they may be acquiring certain skills more slowly than their peers. However, with early intervention and support, children with developmental delays often catch up and bridge the gap.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD):

Developmental disabilities, unlike developmental delays, typically persist throughout a person’s life. ASD, for example, is a neurodevelopmental disorder that becomes evident in early childhood. Children with ASD face challenges related to social interaction, forming relationships, and using language effectively. These conditions are considered lifelong and may require ongoing support and interventions.

Differentiating Between the Two:

Determining whether your child has a developmental delay or a developmental disability can be challenging, as some characteristics may overlap. Regardless of the specific diagnosis, early intervention remains the cornerstone of support for children facing developmental challenges. Timely and tailored interventions can promote progress and overall well-being.

While developmental delays often involve temporary skill acquisition lags that can be addressed with intervention, developmental disabilities like autism spectrum disorder are typically persistent conditions that require ongoing support. Early intervention is universally recognized as the most effective approach for helping children with diverse developmental needs to make meaningful progress and thrive.

FAQ

What are the 4 causes of developmental delay?

Developmental delays can be brought on by prematurity, illnesses (from stroke to persistent ear infections), lead poisoning, and trauma, but sometimes the cause is not understood.

What are the 4 types of developmental delays?

A developmental delay occurs when a kid continuously lags behind peers in achieving developmental milestones. Developmental delays come in four main categories. They include socioemotional, cognitive, sensorimotor, and speech and language disabilities.

Does developmental delay go away?

The phrases developmental delay and developmental impairment are occasionally used interchangeably by doctors. But they’re not the same. Delays in development can be overcome or children can catch up. People with developmental disabilities can still thrive and make progress, but it is a lifetime condition.

Is there a test for developmental delay?

For patients with developmental delay (DD), intellectual disability (ID), or autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) of unknown cause, chromosomal microarray (CMA) is the suggested first-tier diagnostic test.

What is the most common developmental delay?

Delays in the development of language and speech. These delays in toddlers are not rare. Delays in language and speech development are the most typical kind.

Why is my child not speaking at 3?

Children with established conditions, such as Down syndrome, autism, or motor speech issues (dyspraxia), may still be developing foundational abilities in the years before kindergarten. A youngster who is not communicating at ages 3 and 4 and has no recognized medical condition, however, should unquestionably seek professional guidance.

Reference

- Professional, C. C. M. (n.d.). Developmental Delay in Children. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/14814-developmental-delay-in-children

- Pietrangelo, A. (2023, April 24). What You Need to Know About Developmental Delay. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/developmental-delay#autism

- Khan, I. (2023, July 17). Developmental Delay. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562231/

- Types of Developmental Delays in Children. (n.d.). NYU Langone Health. https://nyulangone.org/conditions/developmental-delays-in-children/types

- Developmental Delay – Conditions – Neurological – What We Treat – Physio.co.uk. (n.d.). https://www.physio.co.uk/what-we-treat/neurological/conditions/developmental-delay.php

- Developmental Delay / Delayed Milestones. (n.d.). https://www.icddelhi.org/developmental_delayed_milestone.html

One Comment