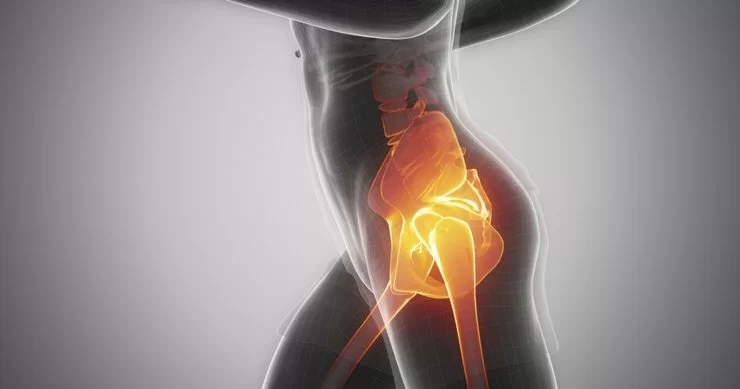

Hip Labral Disorders

Introduction:

Disorders of the hip labrum is an umbrella term that includes any issues involving that labrum such as femoroacetabular impingement (aka FAI) and acetabular labral tear (ALT). This mechanically induced pathology is thought to result from excessive forces at the hip joint. For example, a tear could decrease the acetabular contact area and increase stress, which would result in articular damage, and destabilize the hip joint.

A hip labral tear involves the ring of cartilage (labrum) that follows the outside rim of your hip joint socket. Besides cushioning the hip joint, the labrum acts like a rubber seal or gasket to help hold the ball at the top of your thighbone securely within your hip socket.

Athletes who participate in sports such as ice hockey, soccer, football, golf and ballet are at higher risk of developing hip labral tears. Structural abnormalities of the hip also can lead to a hip labral tear.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy:

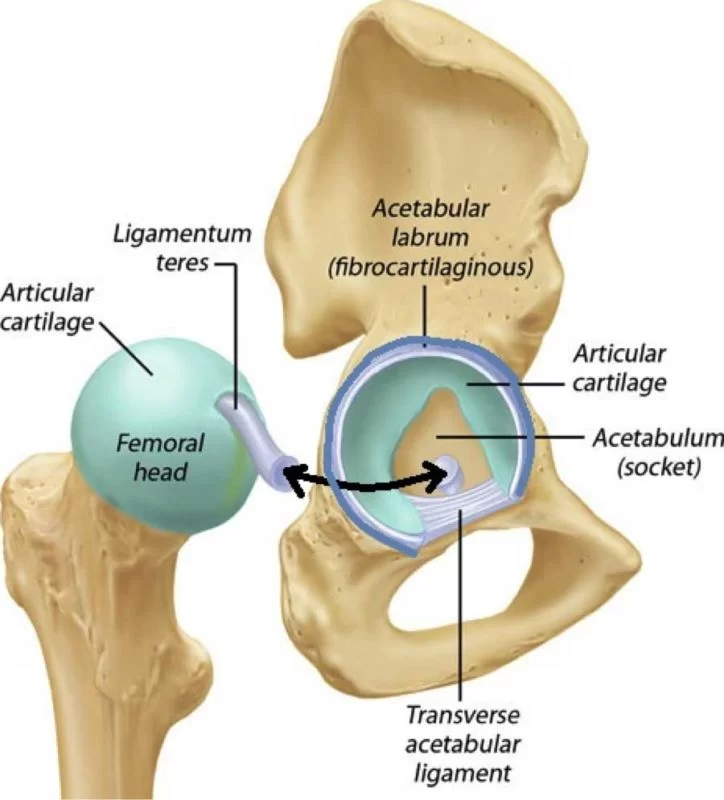

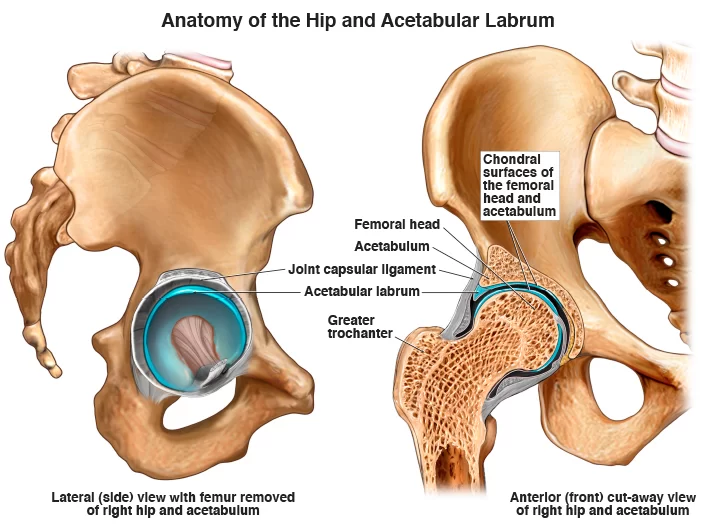

The hip (acetabulofemoral joint) is a synovial joint formed between the femur and acetabulum of the pelvis. The head of the femur is covered by Type II collagen (hyaline cartilage) and proteoglycan that is typically between 2-3mm thick. The acetabulum is the concave portion of the ball and socket joint. The acetabulum has a ring of fibrocartilage called the labrum that deepens the acetabulum and improves the stability of the hip joint.

It lines the acetabular socket and attaches to the bony rim of the acetabulum. It has an irregular shape, being wider and thinner anteriorly and thicker posteriorly. On the anterior aspect, the labrum is triangular in the radial section. On the posterior aspect, the labrum is dimensionally square but with a rounded distal surface.

The labrum has three surfaces:

- Internal articular surface – adjacent to the joint (avascular)

- External articular surface – contacting the joint capsule (vascular)

- Basal surface – attached to the acetabular bone and ligaments

The transverse ligaments surround the hip and help hold it in place while moving.

It is thought that the majority of the labrum is avascular with only the outer third being supplied by the obturator, superior gluteal, and inferior gluteal arteries. There is controversy as to whether there is a potential for healing with the limited blood supply and this is an important clinical consideration. The superior and inferior portions are believed to be innervated, containing both free nerve endings and nerve sensory end organs (giving the senses of pain, pressure, and deep sensation)

The functions of the acetabular labrum are:

- Joint stability – increases the containment of the femoral head, deepening the joint by 21%, and increasing the surface area of the joint by 28%, thus allowing a wider area of force distribution and resisting lateral and vertical motion within the acetabulum

- Sensitive shock absorber

- Joint lubricator – sealing mechanism keeps the synovial fluid in contact with the articular cartilage

- Pressure distributor – obstructs fluid flow in and out of the joint through a sealing action which is often referred to as a “suction effect” in view of the resistance generated to distraction of the head from the acetabular socket. This sealing function not only enhances joint stability but is thought to more uniformly distribute compressive loads applied to the articular surfaces, thereby reducing peak cartilage stresses during weight-bearing.

- Decreasing contact stress between the acetabular and the femoral cartilage

Epidemiology/Aetiology:

The labrum of the hip is susceptible to a traumatic injury from the shearing forces that occur with twisting, pivoting, and falling. Direct trauma (e.g. motor vehicle collision) is a known cause of acetabular labral tearing.

Additional causes include acetabular impingement, joint degeneration, and childhood disorders such as Legg-Calve-Perthes disease, congenital hip dysplasia, and slipped capital femoral epiphysis.

While most tears occur in the anteriosuperior quadrant, a higher-than-normal incidence of posterosuperior tears appears in the Asian population due to a higher tendency toward hyperflexion or squatting motions. The most common mechanism is an external rotation force in a hyperextended position. Microtrauma is believed to be responsible for labral lesions in cases where pain develops gradually.

- Hip labral tears commonly occur between 8 to 72 years of age and on average during the fourth decade of life

- Women are more likely to suffer than men

- 22-55% of patients that present with symptoms of hip or groin pain are found to have an acetabular labral tear

- Up to 74.1% of hip labral tears cannot be attributed to a specific event or cause

- Hyperabduction, twisting, falling or a direct blow from a car accident were common mechanisms of injury in patients who identified a specific mechanism of injury.

- Women, runners, professional athletes, and participants in sports that require frequent external rotation and/or hyperextension are at increased risk of a hip labral tear.

- Those attending the gym three times a week have an increased risk of developing a hip labral tear

Mechanism of Injury:

There are five common mechanisms of labral tears that are widely recognized:

- Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI)

- Trauma: This can occur due to a shearing force associated with twisting or falling, mis-stepping on uneven ground, or colliding with bicycles or vehicles. Repetitive hip hyperextension and external rotation (e.g. during terminal stance in running) can create stress at the chondrolabral junction (typically the 10-12 o’clock position) resulting in microtrauma and eventual labral injury. It may also be associated with iliopsoas impingement resulting in labral injury at the 3 o’clock position.

- Capsular Laxity: This is thought to occur in one of two ways; cartilage disorders (e.g. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome) or rotational laxity resulting from excessive external rotation. These forces are often seen in certain sports including ballet, hockey, and gymnastics.

- Hip Dysplasia: Certain abnormalities of the femur. acetabulum or both (e.g. shallow acetabulum, femoral or acetabular anteversion, decreased head offset or perpendicular distance from the center of the femoral head to the axis of the femoral shaft) can lead to inadequate containment of the femoral head within the acetabulum, placing increased stress into the anterior portion of the hip joint resulting in impingement and possible tears over time.

- Degeneration

Classification:

Labral tears can be classified in different ways.

- Etiology

- Location

- Morphology

- Anterior tear: The pain will generally be more consistent and is situated on the anterior hip (anterosuperior quadrant) or at the groin. They frequently occur in individuals in European countries and the United States.

- Posterior: These are situated in the lateral region or deep in the posterior buttocks. They occur less frequently in individuals in European countries and the United States but are more common in individuals from Japan.

- Superior/lateral

- Radial flap: most common, disruption of the free margin of the labrum

- Radial fibrillated: the fraying of the free margin, associated with degenerative joint disease

- Longitudinal peripheral: least common

- Unstable / Abnormally mobile: can result from a detached labrum.

What are the Symptoms of Hip Labral Disorders?

- There is some variation in the presentation of hip labral tears.

- Patients frequently present with anterior hip and groin pain, although less common areas of pain include anterior thigh pain, lateral thigh pain, buttock pain, and radiating knee pain.

- The majority of patients (90%) diagnosed with acetabular labral tears have had complaints of pain in the anterior hip or groin.

- This can be an indication of an anterior labral tear, whereas buttock pain is more consistent with posterior tears and less common

- Mechanical symptoms associated with a tear are clicking, locking, popping, giving way, catching, and stiffness.

- Patients often describe a dull ache that increases with activities such as running, brisk walking, twisting movements of the hip, or climbing stairs.

- pain in the groin; 1) Flexion, adduction, and internal rotation of the hip joint are related to anterior superior tears and 2) Passive hyperextension, abduction, and external rotation are related to posterior tears.

- Functional limitations may include prolonged sitting, walking, climbing stairs, running, and twisting/pivoting.

- The symptoms can have a long duration, with an average of greater than two years.

- The patient may report experiencing an audible pop or a sensation of subluxation at the time of the trauma if there was a specific traumatic onset.

Differential Diagnosis

List for differential diagnosis of labral injury causing hip pain:

- Contusion (if over bony prominences)

- Strains

- Athletic pubalgia

- Osteitis pubis

- Inflammatory arthridites

- Piriformis syndrome

- Snapping hip syndrome

- Bursitis (trochanteric, ischiogluteal, iliopsoas)

- Osteoarthritis of femoral head

- Avascular necrosis of femoral head

- Septic arthritis

- Fracture or dislocation

- Tumors (malignant and benign)

- Hernia (inguinal or femoral)

- Slipped capital femoral epiphysis

- Legg-Calve-Perthes disease

- Referred pain from lumbosacral or sacroiliac regions

Diagnostic Procedures

MR arthrogram has typically been preferred over MRI because it has shown greater accuracy in identifying defects in the labrum and cartilage

Examination:

Diagnosis should be aided by a physical examination of a patient. In some cases the first signs can be spotted while observing the patient; during a brief walk, the ipsilateral knee may be used to absorb the shocks created by ground reaction forces thus presenting with a flexed knee gait.

Additionally related to gait, the step length of the affected leg may also be shortened, again to reduce the nociceptive input caused by walking. Aside from simple observation, there are a number of provocative tests that can be performed. Because each test stresses a particular part of the acetabular labrum, they can also give an indication of where the tear is located.

Labral tears can be difficult to differentiate from FAI and the two conditions can be present simultaneously. Pain from an isolated labral tear may be associated with hip extension (compared to hip flexion for FAI) as well as signs of laxity. Tightness in iliopsoas or pain with resistance testing of iliopsoas may indicate iliopsoas impingement is associated with labral tearing but not FAI.

Provocative Tests:

Strong evidence in support of provocative clinical tests for diagnosing hip labral disorders is lacking. They found that most of the tests were predominantly sensitive but not specific and that none was capable of significantly shifting the post-test probability of a diagnosis of acetabular labral tear.

The following provocative tests have been indicated as useful in diagnosing hip labral disorders but because of low clinical accuracy (especially specificity), their results should be evaluated within the context of patient presentation and examination;

- McCarthy test, The affected hip needs to be brought into extension. If this movement reproduces a painful click, the patient is suffering from a labral tear.

- FABER Test, flexion-abduction-external rotation test elicits 88% of the patients with an articular pathology. However, this test is non-specific and should be considered a general test for hip articular surfaces

- Anterior labral tear, the patient’s leg has to be brought into full flexion, lateral rotation, and full abduction. Then the leg has to be extended with medial rotation and adduction. Patients with an anterior labral tear will experience sharp catching pain and in some cases, there might be a “clicking” of the hip.

- Posterior Labral tear, To test for a posterior labral tear, the PT performs passive extension, abduction, external rotation, from the position of full hip flexion, internal rotation, and adduction while the patient is supine. Tests are considered to be positive for pain reproduction with or without an audible click.

- Impingement Test (Flexion-Adduction-Internal Rotation Test/FADIR), the patient is placed in a supine and the examiner passively flexes the hip to 90 degrees while performing adduction and internal rotation. Similar to the FABER test, this should be considered a generalized test additionally, test positions and definitions of a positive test vary in the literature.

- Fitzgerald’s Test: Purpose: To assess for a labral tear. Test Position: Supine. Performing the Test: To assess for anterior labral tears: the affected limb is placed in full flexion, lateral rotation, and abduction. The examiner then extends the hip passively, while moving it through medial rotation, and adduction as well. To assess for posterior labral tears: begin with the affected hip in full flexion, adduction, and medial rotation. The examiner then extends the hip passively, while moving it through lateral rotation, and abduction. A sharp pain in the anterior hip is a positive test for a labral tear. Clicking may or may not be audible.

- Resisted SLR

- Anterior hip impingement test

Treatment

Medical Management

The most common treatment and usually the first step on the treatment ladder is conservative treatment and medication (NSAIDs). When conservative treatment does not resolve symptoms, surgical intervention may be appropriate.

The most common procedure is an excision or debridement of the torn tissue by joint arthroscopy. However, studies have demonstrated mixed post-surgical results. Arthroscopic detection of chondromalacia was an even stronger indicator of poor long-term prognosis.

For a simple tear, surgery involves a bioabsorbable suture anchor being placed over the tear to stabilize the fibrocartilaginous tissue back onto the rim of the acetabulum when the labrum has detached from the bone.

If the pathology is caused due to a malalignment (e.g. Perthes or hip dysplasia), femoral or pelvic osteotomies are considered. A femoral osteotomy is a surgical treatment where the femur is cut and angled differently in an attempt to improve the mechanics of the leg.

Surgical treatment

Repair of the acetabular labral lesion can be performed in either the supine or lateral position. In the supine position, a stand fracture table is used with an oversized perinal post to apply traction. The affected hip is placed into slight extension/adduction to allow an approach to the joint. During traction, it is important that there is minimized pressure in the perineal area to avoid neurologic complications. The procedure is under the guidance of fluoroscopy. If the distraction is obtained a 14 or a 16-gauge spinal needle is inserted into the joint to break the vacuum seal and allow further distraction. Three portals are used (the anterolateral, anterior, and the distal lateral accessory).

For repair of a detached labrum, the edges of the tear are delineated and suture anchors are placed on top of the acetabular rim in the area of detachment. If the tear in the labrum has a secure outer rim and is still attached to the acetabulum, a suture in the mid substance of the tear can be used to secure it.

Physiotherapy Management

Conservative Rehabilitation

When conservative management is unable to control the patient’s symptoms, surgical intervention may be considered

Post-surgical Rehabilitation

Movements that cause stress in the area need to be avoided. The rehabilitation protocol following acetabular labral debridement or repair is divided into four phases.

Phase 1. Initial exercise (week 1-4)

The primary goals following an acetabularlabral debridement or repair are to minimize pain and inflammation and initiate early motion exercises. This phase initially consists of isometric contraction exercises for the hip adductors, abductors, transverse abdominals, and extensor muscles. Following a labral debridement, closed-chain activities such as low-level leg press or shuttle can begin with limited resistance.

Weight-bearing protocol following a debridement is 50% for 7 to 10 days, and non-weight bearing or toe-touch weight bearing for 3 to 6 weeks in case of a labral repair. Unnecessary hypomobility will limit progress in future phases, thus it is important to ensure that the patient maintains adequate mobility and range during this phase.

Treatment modalities:

- Aquatic therapy is a suitable treatment approach – movement in the water allows for improvement in gait by allowing appropriate loads to be placed on the joint without causing unnecessary stress to the healing tissue. For example, the patient may perform light jogging in the water using a flotation device. It is important to know the patient’s range of motion precautions, as these may vary in debridement or repair.

- Manual therapy for pain reduction and improvement in joint mobility and proprioception. Considerations include gentle hip joint mobilizations contract-relax stretching for internal and external rotation, long-axis distraction, and assessment of lumbo-sacral mobility.

- Cryotherapy

- Appropriate pain management through medication.

- Gentle stretching of hip muscle groups including piriformis, psoas, quadriceps, and hamstring muscles with passive range of motion.

- A stationary bike without resistance, with a seat height that limits the hip to less than 90°

- Exercises such as water walking, piriformis stretch, and ankle pumps.

- To progress to phase 2, ROM has to be greater or equal to 75%

Phase 2. Intermediate exercise (week 5-7)

The goal of this phase is to continue to improve ROM and soft tissue flexibility . Manual therapy should continue with mobilization that is more aggressive, passive ROM exercises should become more aggressive as needed, for external- and internal rotation.

- Flexibility exercises involving the piriformis, adductor group, psoas/rectus femoris should continue

- Stationary bike with resistance

- Sidestepping with an abductor band for resistance

- Core strengthening such as bridging

- Non-competitive swimming

- Exercises such as wall sits with abductor band, two leg bridging

To progress to the third phase it is important that the patient has a normal gait pattern with no Trendelenburg sign. The patient should have symmetrical and passive ROM measurement with minimal complaints of pain.

Phase 3. Advanced Exercise (week 8-12)

- Manual therapy should be performed as needed

- Flexibility and passive ROM interventions should become slightly more aggressive if the limitations persist (if the patient has reached his full ROM or flexibility, terminal stretches should be initiated)

- Strengthening exercises: walking lunges, lunges with trunk rotations, resistend sportcord, walking forward/backwards, plyometric bounding in the water.

- Exercises such as core ball stabilization, golf progression, lunges

To progress to the forth phases it is important that there is symmetrical ROM and flexibility of the psoas and piriformis.

Phase 4. Sport specific training (12 weeks and more)

- In this phase it is important to return safely and effectively back to competition or previous activity level. Manual therapy, flexibility, and ROM exercises can continue as appropriate.

- It is important the the patient has good muscular endurance, good eccentric muscle control, and the ability to generate power.

- The patient can be given sport-specific exercises and has to have the ability to demonstrate good neuromuscular control of the lower extremity during the activities.

- Exercises such as sport-specific drills, and functional testing.

Prognosis

The majority of patients who have a hip labrum rupture find that their symptoms may be controlled with a mix of therapies. If, despite taking medication or engaging in physical therapy, you are still experiencing pain or other symptoms, consult your provider. They will advise you on when to think about having surgery.

Hip labral tears don’t heal on their own, but that doesn’t mean you have to put up with ongoing pain or discomfort. If you believe that your symptoms are changing, especially if they’re becoming worse or interfering with your normal activities, speak with your provider.

Conclusion

Although learning that something within your body is damaged might be frightening, there are several ways to treat a hip labral tear. Most likely, your doctor will advise starting with nonsurgical therapy for a few months. Many are able to control their symptoms to the point that they can avoid surgery. But after some time, if your discomfort persists, you may require a hip arthroscopy.

Discuss your feelings with your healthcare professional and determine whether surgery is necessary to repair a tear in your hip labrum. Living in constant discomfort is not healthy, and you shouldn’t have to endure it. Tell your healthcare professional the truth about your symptoms and how much they interfere with your daily activities. They’ll assist you in regaining a sense of self.

FAQ

Is it good to walk with hip labral tear?

With a hip labral rupture, many patients are able to walk. Some folks are painless. Others won’t feel quite as comfortable, but they can still walk and move. With a hip labral tear, you may still be able to walk, move, and exercise, although excessive physical activity may not be recommended.

What movements to avoid with hip labral tear?

Additionally, our professionals are able to recognize certain movements—like lunging and straightening your leg out behind you—that should be avoided. These may hurt and put a strain on the labrum.

Can a labrum tear heal without surgery?

Depending on how severe the rupture is, the labrum may occasionally mend on its own with rest and physical therapy.

What is the best treatment for a labral tear in hip?

Your doctor could advise surgery if your hip labral tear is severe or if you have tried nonsurgical methods and your discomfort persists. Arthroscopy surgery is the most often used procedure to treat hip labral injuries. An orthopedic surgeon must make many tiny incisions in order to reach the hip during this treatment.

Is sitting bad for hip labral tear?

Prolonged standing, walking, or sitting might make the discomfort worse. Pain can also result from twisting motions.

Can you live without hip labrum surgery?

Many patients ask about non-surgical hip labral tear rehabilitation. To put it plainly, a hip labral rupture cannot heal on its own without surgery. Nonsurgical therapy, however, can be used to manage many less severe hip labral tears for years, perhaps even permanently.

Is massage good for hip labral tear?

The easiest method to address this is to gradually open and extend the joint itself by using distraction techniques. When this is combined with routine deep tissue massage for the nearby muscles, blood flow is improved and mobility may be increased.