Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block

Introduction

In routine dental practice, the most common anesthetic procedure used by dentists is the inferior alveolar nerve block. Sufficient temporary anesthesia is provided by the inferior alveolar nerve block for several surgical operations. In order to provide a local anesthetic solution close to the nerve’s entrance into the inferior alveolar canal, a needle is inserted into the region around the mandibular foramen.

Located above and posterior to the mandibular foramen, the pterygoid plexus is a crucial anatomical component in the insertion region. Rather than being the result of an uncommon anatomical variation, the primary cause of technical failure in inferior alveolar nerve blocks is incorrect identification of anatomical landmarks. It is reported that the failure rate is between 15% and 20%. The process is often well tolerated, and serious side effects are rare.

Anatomy and Physiology

Branches of the Mandibular Nerve

The third division of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V division V3) is the mandibular nerve. The mandibular nerve splits into anterior and posterior branches when it exits the skull through the foramen ovale at the base of the cranium. The mandibular nerve’s primary stem branches out to supply the meningeal nervus spinosus and the medial pterygoid muscle.

The masseter, lateral pterygoid, and temporalis muscles are supplied mostly by motor fibers found in the anterior division of the mandibular nerve. The anterior division produces the long buccal nerve, a sensory branch. Primarily sensory, the posterior division supplies the lingual, inferior alveolar, and auriculotemporal nerves. The inferior alveolar nerve segments of the mylohyoid muscle before to entering the mandibular foramen. The nerve then passes through the inferior alveolar canal and splits into the incisive and mental nerves, which are its two terminal branches.

Location of Mandibular Foramen

Before accessing the mandibular foramen, the local anesthetic solution needs to be applied close to the nerve in order for an inferior alveolar nerve block to be successful. The appropriate anesthesia can be produced by depositing local anesthetic molecules into the pterygomandibular region, according to a few studies.

There is evidence in the literature that the mandibular foramen’s location can change. The midpoint of the anteroposterior dimension of the mandibular ramus may not always contain the mandibular foramen. The foramen is located around 2.75 mm posterior to the mandibular ramus’s midpoint. Furthermore, it is recommended that the mandibular foramen and coronoid notch be separated by 19 mm and that this distance should be either level with or below the occlusal plane. Age can also affect where the mandibular foramen is located in reference to the occlusal plane. In adults, the mandibular foramen is situated under the level of the occlusal plane; in children, it is situated either at or below the level of the occlusal plane.

Indications

The mandibular teeth in the ipsilateral quadrant, gingival tissue, and mucoperiosteum of the mandibular arch are among the tissues that get temporary anesthesia from the inferior alveolar nerve block. The lower lip’s sensory innervations are also blocked.

This block can be used for a variety of mandibular surgical operations, including periodontal therapy, surgical reconstruction, tooth extraction, root canal therapy, and stabilization in situations of trauma and fracture.

The most frequent dental nerve block, an inferior alveolar nerve block, anaesthetizes the ipsilateral hemi-mandible (teeth and bone), the lateral (buccal) mucosa covering the canine, first premolar, and lower incisors, in addition to the ipsilateral lower lip and chin cutaneously.

The ipsilateral floor of the mouth, medial (lingual) gingiva, and anterior two-thirds of the tongue are all anesthetized via the lingual nerve, which is located nearby and is typically inadvertently occluded.

If anesthesia of the lateral (buccal) gingiva and mucosa of the lower molars and second premolar is required, a buccal block (of the long buccal nerve) is frequently performed as part of the inferior alveolar nerve block operation.

An excruciating mandibular ailment or its management, such

- Fracture (of mandibular bone, alveolar ridge, teeth)

- Dental caries

- Dry socket

- Dental abscess (only in cases where it is located far from the location of the nerve block)

- Laceration (mucosa, lower lip, skin of chin)*

When precise wound edge approximation is crucial (such as in skin or lip restoration), a nerve block may be referred to as local anesthetic infiltration as it does not induce tissue distortion.

Contraindications

Absolute contraindications

Allergy to the anesthetic or delivery vehicle (alternative anesthetics may typically be used)

Lack of physical markers necessary for needle insertion guidance (e.g., owing to trauma)

Relative contraindications

- An inferior alveolar nerve block may not be indicated by a known allergy to a specific local anesthetic, but frequently a different drug can be used in its place. There are no formal contraindications to the surgery itself. The surgery may be postponed until the acute phase of the illness has passed since infection or acute inflammation at the injection site is known to reduce the anesthesia’s effectiveness. Patients who are more inclined to bite their lips or tongue as a result of a prolonged anesthetic effect, such as children or patients with developmental delays, may require extra attention to prevent post-anesthesia traumatic lesions.

- Use procedural sedation or another form of anesthesia if there is an infection at the site of the needle insertion route.

- When possible, treat coagulopathy* before the surgery.

- Pregnancy: If therapy can wait, avoid it throughout the first trimester.

Therapeutic anticoagulation, such as that used for pulmonary embolism, raises the risk of bleeding during nerve blocks; however, if anticoagulation is interrupted, the increased risk of thrombosis, such as stroke, must be evaluated in relation to the increased risk of bleeding. Talk about any planned reversal first with the patient and then with the healthcare provider overseeing the patient’s anticoagulation.

Equipment

When it comes to dental treatments, the most popular anesthetic combination is 2% lidocaine with 1:100 000 epinephrine. It is advised to use 1:50 000 epinephrine for hemostasis in cases where bleeding may be an issue. Because of its vasodilatory action, articaine is commonly used at a concentration of 4% in conjunction with vasoconstrictors. When utilized for the inferior alveolar nerve block, this medication has reportedly been shown to have a longer-lasting impact than 2% lidocaine. To administer the anesthesia, use a dental syringe and a long, sterile, disposable dental needle. To numb the region and lessen pain, topical anesthesia, such as 20% benzocaine, may also be administered to the mucosa before the injection.

- stretcher, dental chair, or straight chair with head support

- The light source for intraoral illumination

- Nonsterile gloves

- a face shield or safety glasses and a mask are necessary

- Gauze pads

- Cotton-tipped applicators

- Dental mirror or tongue blade

- Suction

- Equipment to do local anesthesia:

- Topical anesthetic cream* (e.g., 20% benzocaine, 5% lidocaine)

- An injectable local anesthetic such as bupivacaine 0.5% with epinephrine 1:100,000 or lidocaine 2% with epinephrine 1:100,000 is used for longer-lasting anesthesia.

- a different tiny barrel syringe (such as 3 mL) with a locking hub, or a dental aspirating syringe (with a narrow barrel and customized injectable anesthetic cartridges).

- Regarding nerve blocks, a 25- or 27-gauge needle 3 cm long is used.

WARNING: When dosage limitations are exceeded, poisoning may occur from all topical anesthetic formulations since they are absorbed from mucosal surfaces. Compared to topical liquids and gels with lower concentrations, ointments are simpler to manage. Seldom may too much benzocaine lead to methemoglobinemia.

† Maximum dosage for local anesthetics: 1.5 mg/kg for bupivacaine, 5 mg/kg for lidocaine without epinephrine, and 7 mg/kg for lidocaine with epinephrine. NOTE: 10 mg/mL (1 gm/100 mL) is represented by a 1% solution (of any material). Vasoconstriction brought on by epinephrine prolongs the anesthetic effect; this is advantageous in tissues with good blood flow, such as the mucosa of the mouth. Patients with heart problems should only have small doses of adrenaline (3.5 mL of a solution containing 1:100,000 adrenaline is the maximum); an option is to use a local anesthetic without adrenaline.

Additional Considerations

- Prior to doing a nerve block, note any underlying nerve deficiency.

- Patients who are uncooperative during the operation may require sedation.

- Inadequate placement of the anesthetic relative to the nerve may result in a failed nerve block.

- Every time you try, use a fresh needle since the old one can be clogged with blood or tissue, hiding an accidental intravascular insertion.

- If the patient is not cooperating or you are unclear about where the needle is, stop the nerve block operation and apply another kind of anesthesia.

- Personnel

A helping hand may occasionally be needed to retract the cheek during the delivery of the inferior alveolar nerve block.

Preparation

It is necessary for the operator to stand on the other side from where the injection will be given. In order to facilitate optimal visualization of the anatomical landmarks and needle insertion, the patient is positioned in a semi-inclined posture with their head stabilized on the chair and their mouth open.

To lessen pain during injection, a topical anesthetic, such as 20% benzocaine, can be given to the target location. To improve the topical anesthetic solution’s absorption into the mucosa, this region has to be dried with gauze.

Technique or Treatment

Conventional Technique

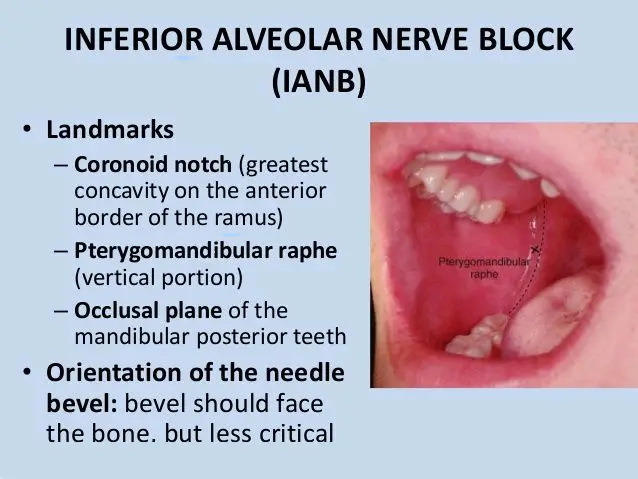

Most frequently, the traditional inferior alveolar nerve block method is employed. It is critical to recognize the coronoid process, coronoid notch, anterior and posterior edge of the mandibular ramus, and sigmoid notch as anatomic markers. The pterygomandibular raphe, which is created by the buccinator and superior constrictor muscles, and the coronoid notch are other noteworthy features. It is ideal to insert the needle between these two structures.

On the side of the injection, the syringe barrel is positioned over the premolars. An imaginary line that begins at the deepest point of the pterygomandibular raphe and extends to the coronoid notch is known as the insertion point. The precise entrance point is situated one-fourth of the way above the mandibular teeth’s occlusal level, towards the raphe. Once the target location has been identified, the needle is entered until bone resistance is felt. The penetration depth ranges from 19 to 25 mm. Subsequently, the needle is slowly and gently removed. The location of the needle may be posterior to the mandibular posterior boundary if it may be placed more than 25 mm. If the bone is contacted before it is ready, the needle may be positioned anteriorly.

Adaptations to the Standard Method

There have been several reports of adjustments or substitutes for the traditional inferior alveolar nerve block method.

- The internal oblique ridge was suggested by Thangavelu et al. as the sole relevant anatomical feature. To use this approach, place your thumb on the retromolar region; the internal oblique ridge will be shown by the tip of your thumb. The location of the insertion will be 6 to 8 mm above the thumb’s midpoint and 2 mm posterior to the internal oblique ridge. The needle is advanced till it comes into contact with the bone after the syringe is placed above the opposing premolars. The success percentage of this method is 95%.

- A 30 mm long needle was used by Boonsiriseth et al., and the insertion site was comparable to the traditional inferior alveolar nerve block method. Nonetheless, the syringe barrel was situated at the ipsilateral teeth’s occlusal level, as opposed to the typical method’s location on the opposing side.

- Suazo Galdames et al. promoted the use of the retromolar triangle technique for inferior alveolar nerve block. Anaesthesia is applied using this approach at the retromolar triangle.

- It is predicated on the fact that the buccal artery, which anastomoses with the inferior alveolar arteries in the mandibular canal, can pass through the bone in this region due to perforations of varying diameters in the bone. Through contact among the mandibular canal with the retromolar triangle, anesthesia applied in this region can reach the inferior alveolar nerve. The success percentage of this method is 72%. In individuals with blood problems, when the traditional inferior alveolar nerve block may be challenging, it can be very helpful.

Other methods that are now accessible focus more on the mandibular nerve branches than the inferior alveolar nerve. They include the Fischer 3-stage approach, the Vazirani or Akinosi closed mouth, and the Gow-Gate technique.

Computer-Controlled Local Anesthetic Delivery (CCLAD)

This automated gadget gently and continually injects a tiny anesthetic solution to lessen the discomfort caused by the injection. There are handpieces that are lightweight, disposable, and intended for single use. These are usually used for anesthesia of the periodontal ligament, the hard palate, and the associated gingiva. In situations where a deep tissue block, such as an inferior alveolar nerve block, is required, these devices may offer anesthesia with more accuracy.

Positioning

- With the mouth open wide and the occiput supported, place the patient in a semi-recumbent sitting posture that is slightly inclined to make the injection site (the medial side of the ramus) accessible.

- Left-handed operators should position themselves on the patient’s left, and right-handed operators on their right.

Detailed Overview of the Process

Preparation

- Put on a face shield, safety glasses, and nonsterile gloves.

- To completely dry the pterygomandibular triangle, use gauze. As necessary, use suction to keep the area dry.

- Using cotton-tipped applicators, apply a small dose of topical anesthetic, then wait two to three minutes for the anesthesia to take effect.

- Put the regional anesthetic in.

- Tell the patient to expand their mouth as wide as they can comfortably.

- To see the vertical height at which the needle will enter, insert the tip of your thumb or fingertip into the coronoid notch. Then, withdraw your cheek to reveal the pterygomandibular triangle.

- Position and hold the syringe’s barrel above the lower first and second premolars on the opposing side.

- Maintain the needle at the vertical plane of the coronoid notch, parallel to and approximately 1 cm above the mandibular occlusal plane.

- The needle tip should now aim into the pterygomandibular triangle with the bevel towards the ramus, resting its side on the lateral border of the pterygomandibular raphe to determine the proper angle of approach and entrance site.

- As the needle advances, keep it inserted at this angle.

- Insert the needle tip just a little bit into the mucosa. To eliminate intravascular implantation, aspirate, and provide a few drops of anesthetic to lessen the discomfort associated with the needle insertion. After gradual improvements of less than 1 centimeter, repeat these little injections.

- Assure the person receiving treatment that the needle is in the proper place if they feel a sudden, acute paresthesia. This feeling may be relieved by slightly withholding the needle and then repositioning it such that it points towards the mandibular foramen and medial ramus.

- After inserting the needle for about 2 to 2.5 cm, advance it until the ramus stops it, then remove it 1 mm from the bone.

- Should the needle miss the mandibular bone, it could have pierced too far posteriorly, such as into the parotid. Remove the needle and reposition it (further forward or backward).

- After the needle makes contact with the ramus, remove it 1 mm from the bone.

- For the purpose of ruling out intravascular placement, aspirate.

- Should aspiration indicate intravascular insertion, remove the needle 2-3 mm and re-aspirate before administering the injection.

- To block the buccal nerve, slowly inject 2 to 4 mL of anesthetic, leaving around 0.5 mL in the syringe.

Block the buccal nerve

Take out the syringe and put it back in at the level of the most posterior molar’s occlusal surface, somewhat anterior and lateral to the anterior border of the ramus. Insert the needle approximately 3 to 5 mm posteriorly. After aspirating to exclude intravascular insertion, administer a 0.25 mL anesthetic injection.

To speed up the onset of anesthesia, massage the injection sites.

Aftercare

As you wait for the anesthesia to take effect (five to ten minutes), have the patient lie down with their mouth relaxed.

Warnings and Common Errors

- In order to reduce the possibility of a broken needle, avoid bending the needle before inserting it, avoid inserting it down to the hub, and tell the patient to stay still, keep their mouth open, and refrain from holding onto your hand.

- For supraperiosteal infiltration, 4% articaine with epinephrine 1:100,000 may be utilized; however, because of a possible danger of long-lasting lingual nerve paresthesia, this combination is not advised for nerve block treatments.

Complications

The degree of complications linked to inferior alveolar nerve block (IANB) varies. Pain and trismus may result from mucosal tears when the needle advances or withdraws. Accidental nicks to the pterygoid venous plexus or intravascular injections of the anesthetic solution might result in hematomas.

An uncommon but documented IANB consequence is facial paralysis. This paralysis might happen right once or gradually.

Soon after the injection, there is immediate facial paralysis, which goes away in about three hours. The duration of the paralysis is equal to that of the local anesthetic; anesthesia including epinephrine often has a longer duration. Direct anesthesia of a facial nerve branch is the most frequent cause of instantaneous facial nerve paralysis. This usually happens after injecting anesthesia into the parotid gland and giving the injection too posteriorly. Since the facial nerve is enveloped by the parotid gland, an intraglandular injection may cause anesthesia to the nerve and subsequent paralysis.

Even with sufficient anesthesia, facial paralysis can still happen if the facial nerve branches in the retromandibular region have abnormal architecture. A hematoma that compresses the nerve, an air burst during surgery, and direct damage from the needle are among other hypothesized reasons for acute facial paralysis.

After IANB, delayed facial nerve paralysis develops many hours to days later, with a 24- to multi-month recovery period possible. This kind of paralysis has several different and intricate aetiologies. Local trauma may occasionally cause a dormant varicella-zoster or herpes simplex infection to reactivate, inflaming the neural sheath.

Axonal ischemia in other circumstances may result from the delayed reflex spasm of the nerve’s vasa nervorum, which might be brought on by the needle’s mechanical action, the presence of anesthetic metabolites, or the anesthesia’s infiltration. It has been proposed that both the intraarterial anesthesia injection and direct injury or ischemia of the facial nerve brought on by excessive strain during lengthy dental treatment may cause delayed paralysis.

There have also been reports of paresthesia, dysesthesia, and lingual nerve paralysis. Ptosis, abducens nerve palsy, skin necrosis across the chin, extraocular muscular paralysis, and diplopia are some rare consequences.

Below are the few conditions that can complicate the condition:

- Allergic reaction to the anesthetic

- Overdosing on anesthesia-related toxicity (such as seizures and heart arrhythmias)

- Intravascular injection of anesthetic/epinephrine

- Hematoma

- Neuropathy

- simply inserting a needle into an affected location, an infection can spread

- Anesthesia of facial nerve branches (cranial nerve VII) as a result of a too-posterior needle insertion

- Absence of anesthesia

- Loss and fracture of needles in soft tissues

- The majority of problems stem from improper needle placement.

Clinical Significance

When done appropriately, the inferior alveolar nerve block produces good anesthesia for the period required to execute standard dental treatments, including the ipsilateral mandibular teeth, gingiva, mucoperiosteum, and lower lip. In any situation, providers need to choose the best approach and be aware of the necessary anatomical landmarks and stages. The traditional approach is the most commonly utilized methodology, even though several techniques have been reported.

Overview

In order to block the inferior alveolar nerve, a local anesthetic solution is injected close to the mandibular foramen and the nerve’s entrance into the inferior alveolar canal. Due to its ability to ease many surgical operations, this anesthetic approach is often employed in normal dentistry practice. In addition to reviewing pertinent anatomy and indications for the inferior alveolar nerve block, this activity explains various techniques that make administering the anesthetic agent easier and emphasizes the importance of the interprofessional team in improving patient outcomes.

FAQs

What are the 5 landmarks of the inferior alveolar nerve block?

The operator should be aware of the following basic mandibular anatomical landmarks, which can be employed in the inferior alveolar nerve block: the condyle, the sigmoid notch, the anterior and posterior borders of the jaw, and the coronoid process and notch.

What is the inferior alveolar nerve block?

A procedure called inferior alveolar nerve block (IANB) is performed to anesthetize the lower lip, mandibular teeth, and mandibular gingiva.

Where do you inject inferior alveolar nerve block?

Parallel to and around one centimeter above the mandibular occlusal plane, the needle is inserted posterolaterally into the pterygomandibular triangle. As the needle goes through connective tissue and muscle, it will run against resistance.

Where is the target area of the inferior alveolar nerve block?

The following mouth regions require an inferior alveolar nerve block to function: teeth on the mandible to the midline. the tongue’s anterior two-thirds. the oral cavity’s floor.

What is the rule of 10 in the inferior alveolar nerve block?

When this number is multiplied by the child’s age (in years), an infiltration analgesic is the most appropriate treatment option; if the number is larger than 10, an inferior oral nerve block is probably more beneficial.

References

- Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK5643

- How To Do an Inferior Alveolar Nerve Block. MSD Manual Professional Edition. https://www.msdmanuals.com/en-in/professional/dental-disorders/how-to-do-dental-procedures/how-to-do-an-inferior-alveolar-nerve-block