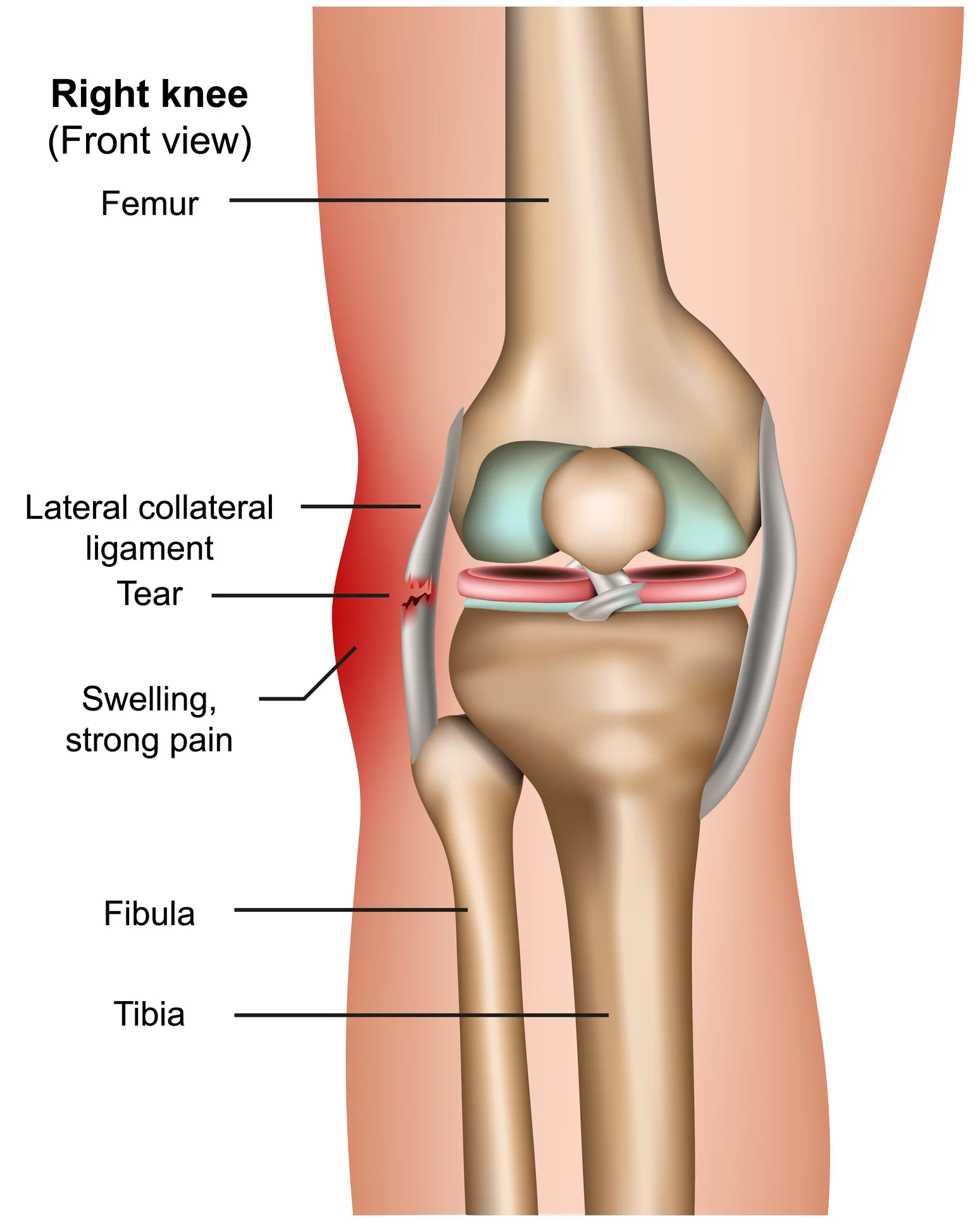

Lateral Collateral Ligament

The lateral collateral ligament (LCL) extends from the outside portion of the lower leg bone, the fibula, to the outside portion of the lower thigh bone. It’s situated outside of your knee. The ligament aids in maintaining the stability of your knee joint’s exterior.

An injury that presses on the inside of the knee joint, causing stress on the outside of the joint, is typically the cause of a lateral collateral ligament (LCL) injury.

Introduction

One of the main ligaments that stabilises the knee joint is the lateral collateral ligament (LCL), also known as the fibular collateral ligament. Its main function is to prevent the knee from rotating too much to the posterior or varus.

A high-energy hit to the anteromedial knee, combining hyperextension and excessive varus force, is the most prevalent cause of an injury to the lateral collateral ligament (LCL) of the knee, while it occurs less frequently than other ligament injuries.

Non-contact varus stress or non-contact hyperextension can also cause an injury to the LCL. Sports involving high-velocity pivoting and jumping, including football, hockey, basketball, skiing, or soccer, account for 40% of all LCL cases. The sports with the highest risk of an isolated LCL injury are tennis and gymnastics.

There are three possible LCL injuries: sprain (grade I), partial rupture (grade II), and total rupture (grade III). When the lateral knee components are injured, the LCL is frequently accompanied by additional injury to the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), and posterior-lateral corner (PLC). This is because the LCL is rarely injured alone.

A crucial band of tissue on the outside of your knee is called the lateral collateral ligament, or LCL. It is more likely to be torn by athletes, which can result in severe pain and other symptoms. LCL tears typically heal in three to twelve weeks, depending on how bad they are. But you have to look after yourself. Apply ice to your knee, use crutches, and pay attention to what your doctor tells you.

Anatomy of Lateral Collateral Ligament

Origin: The lateral epicondyle of the femur, a bony protrusion on the outside of the thigh bone (femur), is the source of the LCL. This is the proximal attachment point of the ligament.

Insertion: The distal attachment point of the LCL is on the head of the fibula, which is the smaller of the two bones in the lower leg. The ligament inserts onto the fibula just below the knee joint.

The insertion of this ligament is enhanced by the iliotibial band, and it is closely related to the joint capsule at the proximal level, albeit without direct contact due to a fat pad separating them. The popliteus tendon divides the lateral meniscus from the LCL because it is positioned deep to it. The biceps femoris is further divided into two sections by the LCL.

The tibia, or shinbone, the patella, or kneecap, and the femur, or thighbone, come together to form the knee joint. For minor protection, the kneecap rests in front of the joint.

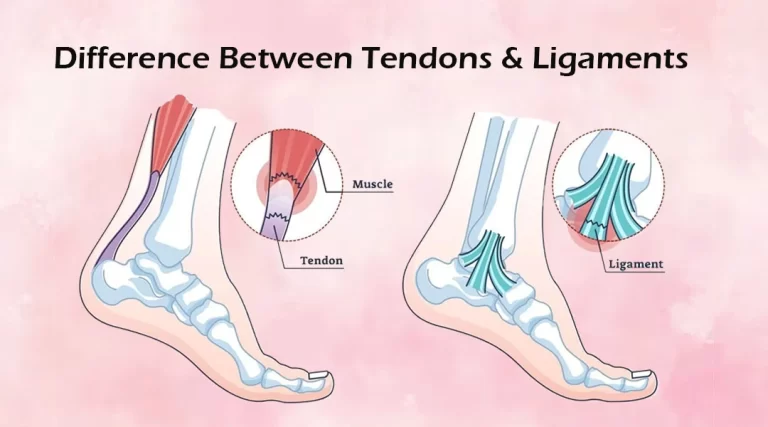

Ligaments attach a bone to another bone. Your knee consists of four main ligaments. They maintain the stability of your knee by acting as sturdy cords to hold the bones together.

Collateral ligaments. On either side of your knee are these. Your knee is braced against abnormal movement and its side-to-side mobility is controlled.

An internal structure is the medial collateral ligament (MCL). It joins the tibia and femur.

The outermost structure is the lateral collateral ligament (LCL). It joins the smaller lower leg bone, the fibula, to the femur.

Cruciate Ligaments. They are situated within the knee joint. The anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments cross over to form an X, with the anterior ligament in front and the posterior ligament behind. The cruciate ligaments govern how your knee moves forward and backward.

Anterolateral fibular head 4,5 is where the LCL inserts after emerging from an osseous depression slightly posterosuperior to the lateral femoral epicondyle. Its typical length is approximately 50 mm, and it resembles a cord rather than a band.

It is less prone to injury and more flexible than the medial collateral ligament because it is not attached to the lateral meniscus or knee capsule.

The lateral epicondyle of the femur bone, a bony projection on the outside of the lower end of the thigh bone, is the source of the lateral collateral ligament (LCL). The lateral epicondylar ridge, a tiny depression located directly below the lateral epicondyle, is where the LCL specifically begins.

The LCL extends from its origin to the head of the fibula bone, where it inserts, running downhill and slightly backward. Muscle attachment points are found on the long, thin fibula bone, which is situated on the outside of the lower leg. Part of the knee joint, the head of the fibula is a rounded bony prominence at the top of the bone.

Two different locations on the fibula bone are where the LCL inserts. The first point of insertion is located on the flat, outward-facing lateral surface of the fibular head, on top of the bone. The second point of insertion is located on the backward-facing, curved posterior aspect of the fibular head.

Lastly, the LCL inserts into two different locations on the head of the fibula bone from its lateral epicondyle of the femur bone. The LCL attachment sites are crucial for stabilizing the knee joint and limiting excessive rotational and side-to-side motions.

Function of Lateral Collateral Ligament

When there is varus stress and posterolateral rotation of the tibia concerning the femur, the LCL stabilizes the lateral side of the knee joint. When the cruciate ligaments are torn, the LCL functions as a backup stabilizer for the anterior and posterior tibial translation.

The main restriction is on varus rotation between 0 and 30 degrees of knee flexion. The LCL’s role as a structure that stabilizes the varus decreases as the knee flexes. LCL stretching occurs when the knee is extended.

The lateral collateral ligament (LCL) is essential for maintaining knee joint stability and limiting the tibia’s (the shin bone) excessive lateral (outward) movement about the femur (the thigh bone). This is a concise summary of its main purpose:

- Resisting Varus Forces: The LCL’s primary job is to withstand varus forces. The forces that push the knee joint outward and away from the body’s midline are known as varus forces. These forces usually manifest themselves during sports-related cutting motions or abrupt direction changes. By acting as a stabilizer, the LCL resists these varus forces and preserves the integrity of the knee joint.

- Stabilizing the Lateral Aspect of the Knee: The LCL, in conjunction with other structures like the biceps femoris tendon and the iliotibial band (IT band), aids in preserving the lateral aspect of the knee joint’s general stability. Maintaining correct alignment and function during weight-bearing exercises like walking, running, and jumping requires this stability.

- Supporting Ligamentous Integrity: Together with the other knee ligaments, such as the medial collateral ligament (MCL), posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), and anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), the LCL offers the knee joint complete stability and support. When combined, these ligaments lessen the chance of injury and support healthy movement patterns by distributing forces evenly throughout the joint.

- Contributing to Joint Kinematics: The LCL facilitates the knee joint’s fluid and well-coordinated motion by limiting the tibia’s excessive lateral movement. Activities involving direction changes, pivoting, and weight-bearing movements require this function.

All things considered, the lateral collateral ligament is an important structure that is essential to preserving the stability, integrity, and functionality of the knee joint.LCL injuries can impair these processes, resulting in symptoms like pain, decreased mobility, and instability. Thus, diagnosing, treating, and recovering from knee joint injuries requires an understanding of the LCL’s function.

Relations

The lateral inferior geniculate vessels and nerve, a bursa, and the popliteus tendon (via the popliteal hiatus) all extend deeply to the LCL. The iliotibial band is superficial to the LCL and attached to Gerdy’s tubercle.

The knee joint’s lateral collateral ligament (LCL) has several significant connections with nearby knee and lower extremity structures. Comprehending these correlations is essential for conducting a thorough evaluation of knee injuries and their effects on joint stability and functionality. These are the lateral collateral ligament’s primary relationships:

- Femur and Tibia: Attaching the two bones, the LCL extends from the lateral epicondyle of the femur (thigh bone) to the head of the fibula, a bony protrusion on the outside of the knee joint. By limiting the tibia’s excessive lateral movement about the femur, it aids in stabilizing the knee.

- Fibula: The lateral aspect of the knee joint is stabilized by the LCL, which is attached to the head of the fibula. As a secondary point of attachment for the ligament, the fibula distributes forces and maintains the overall structural integrity of the lateral knee structures.

- Popliteus Tendon: The popliteus tendon is closely linked to the LCL. It emerges from the lateral femoral condyle and inserts into the posterior aspect of the tibia. Together, these structures help to unlock the knee during the early phases of knee flexion and stabilize the lateral aspect of the knee.

- Iliotibial Band (IT Band): The iliotibial band is a thick fascia band that connects the hip to the tibia on the lateral aspect of the thigh. The IT band and the LCL are not directly related, but they do have a functional relationship that helps stabilize the lateral aspect of the knee and can affect the knee joint’s biomechanics.

- Biceps Femoris Tendon: One of the hamstring tendons, the biceps femoris tendon, connects to the fibular head close to the LCL’s insertion point. Together, these structures give the lateral knee complex support and stability.

- Peroneal Nerve: The LCL and the peroneal nerve are nearby as it passes along the lateral aspect of the knee. Occasionally, nerve damage or irritation from knee injuries, including those involving the LCL, can result in deficits in the lower leg and foot’s sensory or motor function.

Effective diagnosis and treatment of knee injuries depend on an understanding of the connections between the lateral collateral ligament and surrounding structures. Knee stability, function, and overall lower extremity biomechanics can all be affected by dysfunction or injury to one of these structures.

Innervation

- The muscular branch of the tibial nerve is called the biceps femoris.

- At the popliteal fossa, split off from the common fibular nerve.

- At the head of the fibula, is a branch of the common fibular nerve.

Neural structures that transmit sensory feedback from the knee joint’s lateral collateral ligament (LCL) to the central nervous system are involved in the innervation of the ligament. Although the LCL lacks sensory nerve fibers within its structure, it is surrounded by tissues that do have innervation.

These structures are involved in the detection of mechanical stress as well as the transmission of sensory data about joint position and movement. The following are the primary elements involved in the LCL’s innervation:

- Genicular Nerves: The sciatic, femoral, and obturator nerves branch off to form the genicular nerves. Around the knee joint, nerves form a complex network that supplies sensory fibers to a variety of structures, such as the ligaments, periosteum (the outer covering of bones), and joint capsule. The genicular nerves innervate the surrounding tissues, providing sensory feedback related to the mechanical stress experienced during joint movement and loading, even though the LCL lacks direct innervation.

- Peroneal Nerve: A branch of the sciatic nerve that runs along the lateral aspect of the knee is called the peroneal nerve. Although it mainly innervates the lower leg muscles and supplies sensory innervation to the skin of the lateral leg and the dorsum of the foot, it might also be involved in the sensory feedback from the knee joint’s lateral aspect, including structures that are close to the LCL.

- Proprioceptive Feedback: The body’s capacity to perceive position, motion, and force applied to its components is known as proprioception. Ligaments lacking specialized proprioceptive nerve endings, such as the LCL, nevertheless obtain proprioceptive information indirectly from surrounding tissues, including the joint capsule, which has mechanoreceptors responsive to alterations in joint position and movement. Proprioceptive feedback like this helps with coordination and joint stability.

- Referred Pain: Referred pain is a condition in which pain is felt in locations that are far from the actual site of injury due to injuries or stress to the LCL and surrounding structures. For instance, pain referred from the lateral knee structures or the LCL may be felt in different parts of the knee joint or along the peroneal nerve’s distribution.

The surrounding neural structures are vital in providing sensory feedback related to joint mechanics, position, and potential injury, even though the innervation of the LCL itself is restricted. It’s critical to comprehend these neural pathways to diagnose and treat disorders affecting the lateral aspect of the knee joint.

Blood supply

Lateral inferior genicular artery and recurrent artery of the anterior tibia.

Multiple small arteries come from the genicular arterial network that supply blood to the lateral collateral ligament (LCL). The intricate system of tiny arteries known as the genicular arterial network provides blood to the knee joint and the tissues that surround it.

The lateral superior genicular artery and the lateral inferior genicular artery are the principal arteries supplying blood to the left collateral ligament (LCL). These arteries diverge from the popliteal artery, a significant artery situated posterior to the knee joint.

Blood is supplied to the upper part of the LCL by the lateral superior genicular artery, which runs along the outside of the knee joint. Blood is supplied to the lower part of the ligament by the lateral inferior genicular artery, which runs along the lower edge of the LCL.

The LCL receives blood supply from several smaller branches in addition to these arteries. These include the fibular collateral artery, which supplies blood to the lateral side of the knee joint, and the anterior tibial recurrent artery, which supplies blood to the anterior part of the LCL.

Ultimately, the LCL has a comparatively strong blood supply because it receives a constant supply of nutrients and oxygen from several arteries. This contributes to the LCL’s continued strength and health, enabling it to carry out its crucial function of stabilizing the knee joint.

Injuries of the lateral collateral ligament

Injuries to the lateral collateral ligament (LCL) typically occur due to a direct blow to the inner side of the knee, which forces the knee outward beyond its normal range of motion. These injuries can happen during sports activities, particularly those involving contact or sudden changes in direction, such as football, soccer, skiing, or basketball. LCL injuries can range from mild sprains to partial or complete tears of the ligament.

What are LCL tears?

An injury to the knee that results in pain, swelling, and bruises is a lateral collateral ligament (LCL) tear. The band of tissue on the outside of your knee, which faces away from your body, is called your LCL. This tissue joins the bones of your lower limbs to the bone of your thigh. Your knee will no longer bend abnormally outward thanks to it.

Football, soccer, and skiing athletes are more likely to sustain an LCL tear, which could keep them from competing. You should be able to resume playing sports, though, given enough time, care, and rehabilitation.

Here are some common causes and symptoms of LCL injuries:

Causes:

- Direct impact or trauma to the outer side of the knee, such as a tackle or collision in sports.

- Sudden twisting or hyperextension of the knee joint, especially when the foot is planted firmly on the ground.

- Overuse or repetitive stress on the knee joint, particularly in activities that involve frequent pivoting or cutting motions.

Symptoms:

- Pain along the outer side of the knee, especially when bearing weight or bending the knee.

- Swelling and tenderness around the LCL area.

- Instability or feeling of giving way in the knee, particularly when walking or engaging in physical activity.

- Difficulty straightening or bending the knee fully.

- Bruising or discoloration around the knee joint.

Treatment of lateral collateral ligament

First aid for LCL injuries must be administered quickly. This includes icing the injured area, taking painkillers, and raising the knee above the heart. Since the LCL is not always the only ligament harmed, it is critical to get medical attention right away. Surgery is required to stop further instability of the knee when injuries to other ligaments also occur.

Surgery might be necessary if the LCL is the only injury you have; however, if the ligament has torn straight off the bone, therapy for the injury is identical to that for an MCL sprain. Your treatment plan will also take into account any other knee components that may have been affected by your LCL injury.

Conservative treatment

- Rest: Rest is essential to allowing the knee to heal. Avoid painful or uncomfortable activities and limit weight-bearing activities.

- Ice: Keeping your wound iced is crucial to the healing process. Ice should be applied directly to the wounded area for 15 to 20 minutes at a time, with a minimum of one hour elapsed between applications. This is the correct technique to treat an injury. Blue ice and other chemical cold products are not as effective when applied directly to the skin.

- Compression: Wearing a compression bandage or brace can help to reduce swelling and support the knee.

- Elevation: Elevating the injured leg above the level of the heart may help to reduce swelling.

- Bracing: It is necessary to shield your knee from the identical sideways force that injured it. To avoid dangerous moves, you might need to adjust your everyday routine. To prevent stress on the torn ligament, your doctor can advise wearing a brace. Your doctor can prescribe you crutches to prevent you from placing weight on your leg and further safeguard your knee.

- Physical therapy: Your physician might advise strengthening activities. Particular workouts will strengthen the leg muscles that support your knee and help it regain function.

- Medications: Over-the-counter pain relievers like acetaminophen or ibuprofen can alleviate pain and inflammation.

- Injection therapy: Corticosteroid injections can be used to reduce inflammation and pain in the knee.

It is critical to remember that conservative treatment may not be appropriate for all LCL injuries, particularly those that are severe or involve additional knee injuries. In some cases, surgery may be required to repair or reconstruct the LCL. It is critical to consult with a medical professional to determine the best course of action for your particular injury.

Physiotherapy Management

Physiotherapy for an LCL injury combines exercises and manual therapy to promote healing, reduce pain, and inflammation, and improve knee function. Common physiotherapy treatments for LCL injuries include:

- Range of motion exercises: These exercises improve the flexibility and range of motion of the knee. Examples include knee bends, heel slides, and ankle pumps.

- Strengthening exercises: These exercises strengthen the quadriceps, hamstrings, and calf muscles, which support the knee joint. Calf raises, leg presses, and squats are three examples of exercises.

- Balance and proprioception exercises: These exercises improve balance and coordination, reducing the risk of re-injury. Step-ups, wobble-board exercises, and single-leg stands are some examples.

- Manual therapy techniques: These techniques are used to relieve pain and inflammation in the knee joint. Stretching, massage, and joint mobilization are some examples.

- Modalities: Ultrasound, electrical stimulation, and ice/heat therapy can help reduce pain and inflammation in the knee.

- Functional training: Specific exercises mimic daily or sports movements to improve knee function.

Physiotherapy treatment plans vary based on injury severity, age, activity level, and health status. Working closely with a physiotherapist is crucial for creating a personalized treatment plan tailored to your unique needs and goals.

How to reduce the risk of injuries?

Protecting and preserving the stability of the knee joint is necessary to lower the risk of LCL injuries. The following strategies can lower the likelihood of LCL injuries:

- Maintain a healthy weight: Carrying too much weight can increase the strain on the knee joint and raise the possibility of an LCL injury. Reducing this risk can be achieved by eating a balanced diet and exercising regularly to maintain a healthy weight.

- Wear proper footwear: When engaging in physical activity, wearing shoes that provide optimal support and cushioning can help lessen the impact on the knee joint. This may lessen the risk of LCL damage.

- Practice good biomechanics: During physical activity, maintaining proper alignment and form can help lessen knee joint stress and prevent LCL injuries. This could entail learning the right techniques for your sport or activity by working with a coach or trainer.

- Warm-up and cool down properly: It is possible to help prepare the muscles and joints for exercise and reduce the risk of injury by taking the time to warm up before exercise and cooling down afterward.

- Strengthen the muscles around the knee: Enhancing knee stability and lowering the risk of LCL injuries can be accomplished by strengthening the muscles that support the knee joint, such as the hamstrings and quadriceps.

- Use proper equipment: The risk of LCL injuries can be decreased and the knee joint can be protected during physical activity by wearing the appropriate equipment, such as knee braces or pads.

- Rest and recover: After engaging in physical activity, taking some time to rest and recuperate can help avoid overuse injuries, which raise the possibility of LCL injuries.

People can lower their risk of LCL injuries and safeguard the stability and health of their knee joints by following these guidelines.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the lateral collateral ligament (LCL) is an essential component of the knee joint that acts as stability and support, especially when the knee is being forced outward by varus forces. Clinicians must comprehend the structure, function, and clinical implications of the LCL to properly diagnose, treat, and rehabilitate knee injuries.

LCL injuries can vary in severity from minor sprains to full tears, resulting in pain, swelling, instability, and trouble bearing weight on the afflicted leg. An extensive physical examination is necessary for a proper diagnosis, which is frequently enhanced by imaging tests like MRIs.

Depending on how severe the injury is, there are a variety of treatment options for LCL injuries, including bracing, physical therapy, and rest, as well as surgery in more extreme cases. Rehabilitation, which focuses on strengthening muscles, enhancing range of motion, and gradually reintroducing functional activities, is essential to restoring function and stability to the knee joint.

Many people with LCL injuries can return to their pre-injury level of activity and achieve satisfactory outcomes with the right diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation. The severity of the injury, the existence of concurrent knee injuries, and the patient’s compliance with rehabilitation guidelines are some of the variables that affect the prognosis.

In clinical practice, maximizing results and enabling a safe return to activity after LCL injuries require a comprehensive strategy that takes into account the unique needs of each patient. Future research and developments in diagnosis, treatment modalities, and rehabilitation approaches will improve our knowledge and handling of LCL injuries even more.

FAQs

Where did the lateral collateral ligament originate?

The main function of the lateral collateral ligament, which originates on the lateral epicondyle of the femur and inserts on the fibular head, is to stop excessive varus stress and posterior-lateral knee rotation.

What is the anatomy of the MCL and LCL?

The fan-shaped medial (ulnar) collateral ligament (MCL) provides medial support for the glenohumeral and radiohumeral joints. The glenohumeral and radiohumeral joints are similarly supported, but laterally, by the lateral (radial) collateral ligament (LCL). Its structure resembles a cord.

What is the length of the LCL?

The LCL inserts onto the anterolateral fibular head after beginning in an osseous depression that is slightly posterosuperior to the lateral femoral epicondyle. Its typical length is approximately 50 mm, and it resembles a cord rather than a band.

What is the ligament behind the LCL?

The medial collateral ligament is located on the interior (MCL). It joins the tibia and femur. The exterior is home to the lateral collateral ligament (LCL). It joins the smaller lower leg bone, the fibula, to the femur.

What is the anatomical name for the lateral collateral ligament?

As the main knee varus stabilizer, the fibular or lateral collateral ligament (LCL) is a band that resembles a cord. It is one of the four important ligaments that help to keep the knee joint stable.

What is the role of the LCL?

The lateral collateral ligament (LCL), located between the top part of the fibula, the bone on the outside of the lower leg, and the outside portion of the lower thigh bone, located on the outside of your knee, begins. The ligament contributes to the stability of the outside portion of your knee joint.

Where is the LCL located?

A slender band of connective tissue called the lateral collateral ligament (LCL) runs around the outside of the knee. It joins the fibula, the slenderer long bone of the calf, to the femur, the thighbone.

Is MCL bigger than LCL?

Except for the longitudinal diameter of the proximal attachment, the MCL’s attachments were larger than the LCL’s. The MCL had a backward inclination and the LCL had a forward one at full extension of the knee.

Is LCL a ligament or tendon?

A narrow band of tissue that runs the length of the outside of the knee is called the lateral collateral ligament (LCL). Each year, thousands of people suffer from stretches, partial tears, or full tears of the LCL.

Where does LCL connect?

One of the four main ligaments in the knee is the lateral collateral ligament (LCL). On the outside of the knee, the LCL assists in joining the larger shin bone, the fibula, to the thigh bone, the femur. The knee cannot buckle outward because of the LCL.

How can you prevent LCL?

Using a brace on the knee.

Wearing specialized knee braces designed to prevent side-to-side movement is one way that some athletes, like football linemen or snow skiers, try to lower their risk of an LCL tear.

What two bones does the LCL connect?

A thin band of tissue that runs along the outside of the knee is called the lateral collateral ligament. It joins the fibula, the small bone of the lower leg that runs down the side of the knee, and joins the ankle, to the thighbone (femur).

How does LCL stabilize the knee?

The ligament that joins the femur to the fibula is known as the lateral collateral ligament, or “LCL”.Your knee is stabilized in part by the LCL. This ligament aids in preventing excessive side-to-side movement of the knee joint, as does the medial collateral ligament. It maintains the appropriate alignment of the upper and lower legs.

Can you walk with an LCL tear?

When your doctor says it’s safe for you to put weight on your leg, you might also need to wear a hinged knee brace. In three to four weeks, many people are back to their previous level of activity. Injury grades two or above. This might necessitate the use of hinged knee braces and crutches.

Can LCL heal on its own?

It is important to avoid re-injuring the ligament while it heals because it will heal on its own. Range-of-motion exercises and gently strengthening the biceps femoris (hamstring muscles) and quadriceps (thigh muscles) are recommended during the healing phase.

What is the recovery time for LCL surgery?

LCL Surgery Recuperation

After surgery, patients can usually leave the hospital a few hours later, though some may need to stay the night. Following hospital discharge, rehabilitation frequently entails: Using crutches for a maximum of six weeks.

What is the orthopedic test for the LCL?

Varus Stress Test- The most beneficial unique test for evaluating an LCL injury. A varius force is applied with the femur stabilized, paying particular attention to the lateral joint line. First, the test is run with the body in a 30-degree flexion. An LCL injury with potential PLC involvement is indicated by increased laxity or gapping.

How long does it take for LCL to heal?

Grade I: A grade I LCL injury takes approximately three weeks to heal. Grade II: A grade II partial tear of the LCL can require three to six weeks to heal. Grade III: Over six weeks are needed for the LCL to fully mend after a tear.

Are LCL injuries serious?

Tears in the lateral collateral ligament do not heal as quickly as tears in the medial collateral ligament. Surgery might be necessary for grade 3 lateral collateral ligament tears. In certain instances, the only things needed are physical therapy, ibuprofen, braces, rest, and painkillers.

References

- Lateral Collateral Ligament Injury of the Knee. (n.d.). Physiopedia. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Lateral_Collateral_Ligament_Injury_of_the_Knee.

- Image –Redirect Notice. (n.d.). https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fadamcohenmd.com%2Flateral-collateral-ligament&psig=AOvVaw3pYPt-B-wc-8sb_Ps6dF7o&ust=1708088718188000&source=images&cd=vfe&opi=89978449&ved=0CBMQjRxqFwoTCKj4soW_rYQDFQAAAAAdAAAAABAE.

- Collateral Ligament Injuries – OrthoInfo – AAOS. (n.d.). https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/diseases–conditions/collateral-ligament-injuries/.

- Lateral Collateral Ligament of the Knee. (n.d.). Physiopedia. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Lateral_Collateral_Ligament_of_the_Knee.

- Knipe, H., & Su, S. (2014, October 3). Lateral collateral ligament of the knee. Radiopaedia.org. https://doi.org/10.53347/rid-31367.