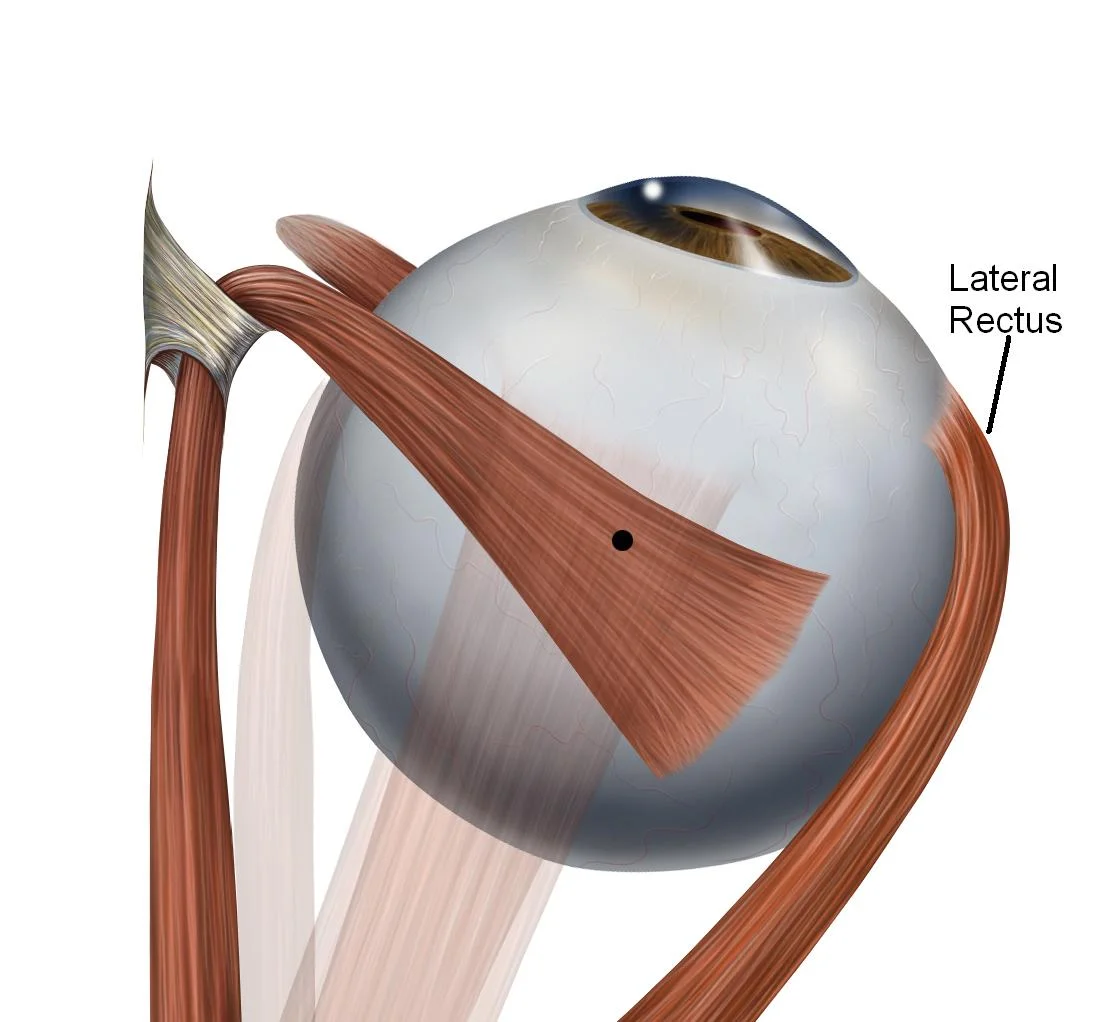

Lateral Rectus muscle

Introduction

The lateral rectus muscle is one of the seven extraocular muscles. These muscles control every eye movement; generally, one muscle moves the eye in one direction, and the combination of all of them allows the eye to move in each direction.

Extraocular muscles include 4 rectus muscles (medial, lateral, superior, and inferior rectus), 2 oblique muscles (superior and inferior), and 1 levator palpebrae superior.

Origin and insertion of Lateral Rectus muscle

The lateral rectus muscle is a flat strap-shaped muscle that is wide from its anterior part. It originates from the lateral part of the common tendinous ring and crosses the superior orbital fissure. Additionally, a small slip originates from the spine on the greater wing of the sphenoid bone.

The muscle then goes anteriorly along the lateral wall of the orbit to insert at the lateral side of the eyeball after crossing the tendon of the inferior oblique muscle. The muscle inserts anterior to the equator of the eyeball, and about 7 mm from the limbus of the cornea.

Structure

The lateral rectus muscle arises in the bottom of the orbital cavity in the surrounding area of the optic canal, specifically in the lateral part of the common tendinous ring; the annulus of Zinn. Almost every extraocular muscle arises in the annulus of Zinn, excluding the inferior oblique muscle and levator palpebrae superiors.

Function of Lateral Rectus muscle

The lateral rectus is a flat-shaped muscle, and it is wide in its anterior part. The lateral rectus muscle is an abductor’s muscle and moves the eye laterally, and side to side along with the medial rectus, which is an adductor.

Embryology

The lateral rectus muscles arise from the mesoderm, like every extraocular muscle. One has to take into account all the connective tissue that arises from neural crest cells. There are some cases in the literature where the lateral rectus or other extraocular muscles have not developed well.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The extraocular muscle’s blood supply can be variable. The blood supply of the lateral rectus depends on the muscular divisions of the ophthalmic artery, as is the case for every extraocular muscle, and, additionally, receives one or two divisions of the inferior muscular artery and the lacrimal artery. The lacrimal artery is a division of the ophthalmic artery, which is a division of the internal carotid artery.

Veins are named as their counterpart arteries and drain into the superior and inferior orbital veins, situated laterally and medially to the superior and inferior rectus muscle. These two veins drain to the cavernous sinus (sometimes directly and a few times the inferior orbital drains into the superior orbital vein and then to the cavernous sinus.); the cavernous sinus drains into the inferior and superior petrosal sinus and then into the internal jugular vein.

Nerves

The lateral rectus muscle is the only muscle that is supplied by cranial nerve VI, (the abducens nerve) by the tectospinal tract.

Muscles

The rectus and extraocular muscles are different from other skeletal muscles of the human body; they have a selected variety of fiber types, which permit these muscles to make fast (saccadic) movements and resist fatigue. The insertions of the rectus muscle are also much more accurate than other muscle insertions; every one of these muscles arises at the annulus of Zinn, extends anteriorly, and inserts on the globe at a particular distance from the limbus. For example, the lateral rectus muscle ends at about 6.9mm from the limbus.

Relations

The ending point of muscle (insertion) of the lateral rectus muscle is around 8 mm from the insertion of the inferior rectus muscle, around 7 mm from the insertion of the superior rectus muscle, and about 10 mm from the corneal limbus.

The lateral rectus muscle expands along the lateral wall of the orbit. It originates from the lateral part of the same tendinous ring near the attachments of the medial, lateral, and superior recti muscles. This tendinous ring surrounds the margins of the optic canal and part of the superior orbital fissure, and still, the attached muscles form a cone that covers the structures entering the orbit. These structures include the optic sheath containing the optic nerve (CN II) and ophthalmic artery, the superior and inferior branches of the oculomotor nerve (CN III), the nasociliary nerve (CN V₁), and the abducens nerve (CN VI).

After starting from the common tendinous ring, the lateral rectus lies lateral to the ciliary ganglion near the apex of the orbit. The lateral rectus muscle then extends along the lateral wall of the orbit towards the eyeball, passing medially to the lacrimal gland. In addition, the lacrimal artery extends along the superior border of the lateral rectus muscle to supply the lacrimal gland.

The fascial sheath of the lateral rectus muscle gives a triangular expansion called the lateral check ligament. This ligament attaches to the orbital tubercle of the zygomatic bone and serves its function of restricting the lateral rectus muscle and limiting the abduction of the eye. The lateral check ligament mixes with the same fascial expansions of the medial and inferior rectus muscles, as well as the superior and inferior oblique muscles. Together, they both form the suspensory ligament of the eyeball, a hammock-like sling that provides support to the eyeball.

Physiologic Variants

The abnormal origin of the lateral rectus muscle is also known to cause misalignment or strabismus. There are case reports of a lack of lateral rectus muscle.

Surgical Considerations

Sometimes, it is important to correct strabismus surgically; by performing surgery, one can correct the malalignment of the eye so that the patient can use both eyes together and reestablish their binocular function. Surgery can also improve the vision of the eyes.

Because of the position of the nerve, it is sometimes possible for it to suffer an injury during surgery; this can happen if the surgeon uses advanced instruments about 3cm posterior to the insertion of the lateral rectus muscle.

The blood supply can also suffer an injury during surgery. The blood vessels that supply lateral rectus muscle also supply blood to half of the anterior part of the eye, specifically, the nasal half of the anterior segment. Thus, the surgeon has to be aware of the vascular supply to the lateral rectus muscle during surgery.

Clinical Significance

The lateral rectus muscle abducts the eye and, consequently, it also allows people to look to the right with the right eye and to the left with the left eye. Clinicians usually test every extraocular muscle at the same time making the patient watch in the nine directions with the eyes following the doctor’s finger or pen tracing an “H” form in the air.

Sometimes further tests, like cover-test, are important to diagnose the pathology of extraocular muscles.

The most common lateral rectus pathology encountered is a sixth nerve palsy, known as abducent nerve palsy. In this case, the patient will not be able to abduct the eye and as a consequence, the patient will experience diplopia or double vision. The diplopia will be binocular, meaning that if the patient covers one eye, he or she will not experiment with double vision. Diplopia which is caused by lateral rectus muscle palsy gets worse when the clinician makes the patient look in the direction of the palsied muscle. For example, in the case of right lateral rectus palsy, the patient will have diplopia when looking to the right. Although complete lateral rectus palsy is very easy to diagnose, sometimes microvascular injury to the nerve causes a “micro palsy,” where the patient seems to have the functions preserved but has double vision.

The most common cause of sixth nerve palsy is a microvascular or vascular injury to the nerve. However, tumors, infections, and inflammation can cause sixth nerve palsy too. The sixth cranial nerve is the most sensitive nerve to hydrocephalus, and this condition should be suspected in any patient who has bilateral lateral rectus palsy. There are very rarer causes of sixth nerve palsy including petrosal sinus thrombosis and autoimmune diseases.

The literature has described lateral rectus myositis, which is a very rare condition and usually reflects a rare inflammatory disorder. Lateral rectus muscle myositis can be a rare presentation of a non-Hodgkin B cell mucosa-associated lymphoma (MALT).

Lateral rectus palsy

Almost all lateral rectus palsies are obtained in later life and are caused by conditions that have injured the VIth cranial nerve, which supplies the lateral rectus muscle.

The causes of lateral rectus palsy are:

Less/poor blood supply to the VIth nerve is caused by a combination of factors such as high blood pressure, diabetes, high cholesterol, and smoking. This is also known as microvascular palsy.

The direct pressure on the VIth nerve caused by tumors, middle ear infections, or swelling of neighboring blood vessels can injure the VIth nerve. Lateral rectus palsy can also be a sign of elevated intracranial pressure.

Head injuries can cause lateral rectus palsy, but this is usually due to elevated intracranial pressure.

Occasionally, inflammation in the part of the nerve can cause lateral rectus palsy.

Typical features of lateral rectus palsy include:

Sudden onset of horizontal double vision, which gets worse when the patient watches the affected side.

Limitation in the outward movement of the affected eye. Patients often compensate for this by moving their heads to the affected side.

Convergent strabismus is large when the patient tries to see an object in the distance.

An Orthoptist and an Ophthalmologist will examine all patients. A detailed history will be taken and specific tests carried out to test the strabismus and examine the range of eye movements. A chart may be plotted to measure the size of the area of a single vision and to measure the movements of the eyes in various directions. Blood tests and an MRI scan are done to investigate what could have caused the palsy.

What are the treatment options?

Most (80%) microvascular superior oblique palsies will resolve in 3-6 months. However, spontaneous recovery is less likely to happen if the lateral rectus palsy has been caused by a head injury or a tumor.

In adults, it may be possible to have temporary plastic prisms fitted to the patient’s glasses that will reduce or in some cases completely resolve the strabismus and double vision. If the angle of the strabismus is too big to correct with prisms, then Botox treatment can be considered.

Botox injections given into the medial rectus muscle will reduce the size of the convergent strabismus. It will also prevent the medial rectus muscle from contracting and shortening, which can cause limited outward movement of the eye, even if the lateral rectus muscle starts to function normally again.

Symptoms

- Double vision or diplopia when watching side to side is the most common symptom of sixth nerve palsy.

Other symptoms may include:

- headache.

- nausea.

- vomiting.

- papilledema or swelling of the optic nerve.

- vision loss.

- hearing loss.

How to treat sixth nerve palsy?

In some cases, treatment of sixth nerve palsy is unnecessary and it improves in time, such as when the disorder is caused by a viral infection that has to run its course. The doctor might monitor your condition over a 6-month period.

Other times, the disorder only improves once the underlying cause has been cured.

Treatment depends on your diagnosis and can include:

Antibiotics. The doctor may prescribe antibiotics if sixth nerve palsy is caused by a bacterial infection.

Steroids. Prescription-strength corticosteroids can cure sixth nerve palsy caused by inflammation.

Surgery. If your condition is caused by intracranial pressure, the doctor may perform surgery to reduce that intracranial pressure. Cancer can also be removed surgically.

Lumbar puncture. This may also be used to reduce pressure in the brain.

Chemotherapy and other cancer treatments. If your sixth nerve palsy is caused by a brain tumor, complementary therapies may reduce or eliminate or treat cancer cells that remain after surgery.

Prism therapy. If the palsy is caused by trauma, the doctor might recommend prism glasses to provide single binocular vision and align your eyes.

Injections. To correct misalignment, a doctor may inject botulinum toxin to paralyze the muscles on one side of your eye.

Strabismus surgery. This surgery may be used to loosen or tighten the eye muscles if other therapies will not correct the double vision.

Alternative patching. This therapy is used in children and consists of wearing an eye patch for a few hours each day while alternating eyes. This can help to prevent lazy eyes.

FAQ :

1. What would happen if the lateral rectus was damaged?

The abducens nerve supplies the lateral rectus muscle of the eye. This nerve is responsible for lateral eye movements. Injury to this nerve will prevent such movement. Injury to this nerve will cause double vision.

2. What is the function of the lateral rectus in the eye?

The lateral rectus muscle is an abductor’s muscle and moves the eye laterally, and side to side along with the medial rectus, which is an adductor muscle.

3. What happens when the lateral rectus muscle contracts?

The lateral rectus muscle abducts the eye, turning the eye in the lateral direction into the orbit.

Which nerve controls lateral eye movement?

The oculomotor nerve is the third (CN III) in the cranial nerves. It does eye movements, such as focusing on an object in motion. Cranial nerve III always helps move your eyes up, down, and side to side.

5. How do you strengthen the lateral rectus muscle?

Lateral rectus exercises

The cardinal point exercise involves watching to the extreme in each direction – up, down, right, and then left. Hold your eyes in that position for ten seconds at each cardinal point. Repeat the exercise about a total of five times. The eye-rolling exercise is exactly the same as what it sounds like.

2 Comments