Long Thoracic Nerve

Introduction

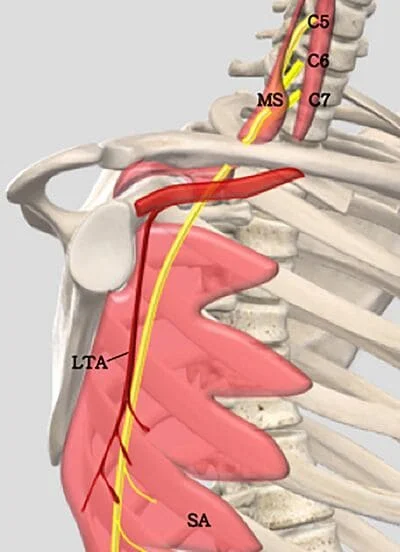

The top portion of the superior trunk of the brachial plexus gives rise to the long thoracic nerve, also known as the external respiratory nerve of Bell or the posterior thoracic nerve. This nerve normally receives support from cervical nerve roots C5, C6, and C7.

The long thoracic nerve travels along the chest wall in the mid-axillary line, lying on the superficial surface of the serratus anterior muscle, innervating it. It descends posteriorly to the roots of the brachial plexus and anteriorly to the scalenus posterior muscle.

The long thoracic nerve is vulnerable to injury during some surgical operations, as well as through direct trauma or stretch, due to its lengthy, relatively superficial route. Winging of the scapula is a condition that occurs when the long thoracic nerve is damaged.

Structure

The serratus anterior muscle, which pulls the scapula forward around the thorax to permit arm anteversion and lifts the ribs to aid in breathing, is controlled by the long thoracic nerve, which serves as its motor nerve. Additionally, the scapula’s anterolateral motion, which permits arm elevation, is caused by the serratus anterior inferior.

The long thoracic nerve travels inferiorly on the chest wall along the mid-axillary line on the outer surface of the serratus anterior muscle for a distance of about 22 to 24 centimeters, passing anterior to the scalenus posterior muscle, distally and laterally deep to the clavicle, and superficial to the first and second ribs. The nerve travels at an estimated 30-degree angle posteriorly, in relation to the anterior axillary line, from where it emerges to the posterior angle of the second rib. The nerve is located posterior to the initial portion of the axillary artery. The nerve travels between the middle and posterior axillary lines from this intersection.

The upper and lower portions of the long thoracic nerve develop from the C5 and C6 and C7 nerve roots, respectively. These two parts come together in the axilla. The top division of the long thoracic nerve passes close to the suprascapular nerve in the supraclavicular area, parallel to the brachial plexus.

The long thoracic nerve’s superficial run over the whole length of the serratus anterior muscle it supplies is one of its distinguishing features. The nerve further splits into tiny branches that travel parallel to the main stem before making a right angle turn and entering the superior aspect of each slip to innervate it. At the proximal edge of the distal serratus anterior head, a collateral branch of the thoracodorsal artery, namely the serratus anterior branch, joins the long thoracic nerve. It eventually crosses the nerve and splits into the terminal muscle branches. Crow’s feet are a marker in flap transfer procedures and are a crucial intersection.

Function

The serratus anterior muscle receives innervation from the long thoracic nerve, a motor neuron. This muscle lifts the ribs to aid in breathing and drags the scapula anteriorly to allow for arm anteversion. For sustained upward rotation of the scapula, which is necessary for overhead lifting, the serratus anterior also works with the trapezius muscle.

Being the only nerve that innervates the serratus anterior muscle, injury to the long thoracic nerve paralyzes this muscle, resulting in a winged scapula.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Prior to the lower part of the scapula, the long thoracic nerve and its blood supply are susceptible to compression and stretching. The lower four to six digits of the serratus anterior muscle and the peripheral segment of the long thoracic nerve are both supplied with blood by the subscapular artery through the inferior angle of the scapula. As a result of compression or traction of the subscapular artery, inadequate epineural blood flow may occur, which may lead to nerve injury.

The fascia anchors the serratus anterior muscle to the long thoracic nerve and its blood supply, which moves with the muscle when it contracts. During arm adduction, the scapula travels anteriorly while also pushing the nerve and blood vessels forward to clear the scapula’s path. The serratus anterior muscle prevents the scapula from winging during arm extension, which avoids stressing the nerve and vascular system.

Muscles

The long thoracic nerve is the only source of innervation for the serratus anterior muscle, also referred to as the “boxer’s muscle,” and when it is injured, the muscle paralyzes, a condition known as a winged scapula. When throwing a punch, the scapula protracts, which is predominantly controlled by the serratus anterior. For sustained upward rotation of the scapula, which is necessary for overhead lifting, the serratus anterior collaborates with the trapezius muscle.

The serratus anterior muscle, which is deep to the subscapularis, is separated into three parts based on their locations of origin and insertion: serratus anterior superior, serratus anterior intermediate, and serratus anterior inferior. As a result, each portion of the muscle is innervated differently by the serratus anterior. Both the real long thoracic nerve and a separate branch that is unconnected to the main trunk of the long thoracic nerve innervate the superior segment.

The independent branch’s path is interestingly similar to that of the nerves responsible for innervating the levator scapulae muscle, indicating a connection between the serratus anterior superior and the levator scapulae muscle. The long thoracic nerve innervates the serratus anterior intermediate, while the inferior segment is innervated by both the long thoracic nerve and a branch of the intercostal nerve.

Physiologic Variantion

While the anterior rami of the C5, C6, and C7 roots of the brachial plexus are where the long thoracic nerve generally emerges, C8 supplies the nerve in about 10% of people. There is evidence of an abnormal connection between the dorsal scapular nerve and the long thoracic nerve. It has also been established that C6 and C7 make up the majority of the long thoracic nerve, which is normally made up of the three ventral rami of the C5, C6, and C7 cervical nerves. There are known cases when the long thoracic nerve’s C5 component was gone, although a connecting branch from C6 was thought to convey C5 fibers in those cases.

Additionally, the C5, C6, and C7 components are normally joined to form the long thoracic nerve in the axillary area. However, there is evidence that the joining of these long thoracic nerve components takes place above the axillary region posterior to the clavicle. This physiological variation raises the risk of nerve damage when treating thoracic outlet syndrome and treating clavicular fractures.

Surgical Considerations

In cases of protracted thoracic nerve injury, the serratus anterior or trapezius muscles are paralyzed, causing a condition known as winged scapula. The risk of proximal injury to the long thoracic nerve increases with procedures in the thoracic region, such as radical mastectomy, transthoracic sympathectomy, transaxillary thoracotomy, misplaced intercostal drains.

Furthermore, a long thoracic nerve damage and subsequent winging of the scapula can occur in young patients undergoing a posterolateral thoracotomy incision for closed heart surgeries or any other procedures involving the separation of the serratus anterior muscles from the latissimus dorsi. In order to improve surgical success rates and lower the chance of inadvertent nerve damage, it is crucial to understand the anatomical course of the long thoracic nerve.

As it has been noted that the nerve roots may be found anterior, posterior, or through the middle scalene muscle, physiological variations in the course of the long thoracic nerve positionally to the muscle may result in iatrogenic nerve injury and subsequent scapular winging.

Additionally, the serratus anterior muscle does not work in conjunction with the other shoulder girdle muscles when the scapula has wings. This issue makes the scapula more likely to move abnormally in relation to the long thoracic nerve. For instance, the control of the shoulder girdle muscles is compromised when a patient is under general anesthesia, and passive adduction of the arm (such as when a patient’s arm is elevated and crossed over his or her chest) may result in the anterior displacement of the scapula. The long thoracic nerve and its blood supply may be compressed, resulting in muscular creasing.

Clinical Importance

Injury to the Long thoracic nerve

Serratus anterior weakness and scapular winging come from the denervation of the long thoracic nerve. Scapula winging may result from any dysfunction or weakness affecting any muscle that stabilizes the scapula. Due to the poor protraction of the scapula, unopposed medial scapula retraction by the rhomboid muscles, and elevation by the trapezius, which results in medial winging of the scapula, a serratus anterior muscle deficiency is the most common cause of winging. Because the spinal accessory nerve supplies the trapezius muscle, which is weak in this condition compared to the far less common lateral winging, it is easy to distinguish between the two.

The long thoracic nerve has a smaller diameter than other brachial plexus nerves, which, when combined with its thin connective tissue and superficial course along the serratus anterior muscle, increases its susceptibility to injury, either surgically or non-operatively, leading to the development of scapular winging. From the axilla down, the long thoracic nerve is comparatively shielded until it reaches the level of the eighth or ninth rib. As a result, the nerve may be exposed to outside harm, such as cast compression, using crutches, anesthetic, or Saturday night palsy.

Long thoracic nerve injuries can occur for a number of reasons, but they can generally be categorized into three groups: non-traumatic, traumatic, and iatrogenic.

Non-traumatic:

- viral illness (influenza)

- tonsillitis-bronchitis

- Poliomyelitis

- allergic drug reactions

- muscular dystrophy (facio-scapulohumeral dystrophy)

- Parsonage-Turner syndrome

Traumatic:

- clavicle or upper rib fractures

- sudden scapular depression

- repetitive arm movements as seen in athletes (especially in athletes that combine contralateral neck and neck movement with arm abduction and external rotation, as in javelin throwing)

- Household tasks like cleaning the car, digging, or spending a long time in bed with an arm raised to read

Iatrogenic injury:

- use of a single axillary crutch

- mastectomy

- axillary node dissection

- scalenectomy

It has been observed that when the long thoracic nerve gets closer to the lower angle of the scapula, less motion of the scapula is needed to compress or stretch the nerve. The varying occurrence of serratus anterior paralysis may be explained by individual variations in the distance between the nerve and the scapula.

Other Related Conditions

The mechanism of nerve injury affects how long thoracic neuropathy is treated and how well it will turn out. For instance, recovery from neuralgic amyotrophy often takes one to three years and is gradual. On the other hand, injuries brought on by repetitive motions or lifting large objects are incomplete and typically heal on their own after 6 to 24 months. Physical therapy and exercise are essential in these situations to maintain range of motion and strengthen accessory muscles like the trapezius and rhomboid muscles.

The long thoracic nerve is typically more severely injured and has a shorter healing time if it is directly injured by the shoulder or the lateral chest wall. If a patient doesn’t recover functionally, they can be considered for surgery. Recent case reports have shown that nerve transfer using the thoracodorsal or medial pectoral nerves has been beneficial in treating some conditions.

The power and symmetry of the bilateral scapulae and serratus anterior muscles are used to evaluate the neural integrity during a clinical examination because the long thoracic nerve innervates these muscles. The serratus muscle wall test can be used to assess and contrast the strength of the serratus anterior and is symptomatic of long thoracic nerve damage if there is any asymmetry, muscular atrophy, or fasciculation found.

The patient pushes against the wall with flat palms at waist level during the serratus wall test while facing the wall from a distance of about 2 feet. Winging (medial winging) of the scapula due to paralysis of the serratus anterior is a symptom of damage to the long thoracic nerve.

FAQs

What is the long thoracic nerve?

The serratus anterior muscle, which pulls the scapula forward around the thorax to permit arm anteversion and lifts the ribs to aid in breathing, is controlled by the long thoracic nerve, which serves as its motor nerve.

What is the origin of the long thoracic nerve?

The posterior thoracic nerve or Bell’s external respiratory nerve are other names for the long thoracic nerve. It starts at the superior trunk of the brachial plexus and then descends anterior to the posterior scalene muscle and behind the brachial plexus.

What are the symptoms of long thoracic nerve damage?

Symptoms of long thoracic nerve damage are:

Pain is viewed as being intense and terrible.

weakness or stiffness when moving the shoulder or arm.

Numbness or tingling

decreased range of motion (while doing overhead exercise)

Scapular ‘winging’ or deformity that is obvious (also observed after wall press-ups)

Shoulders appear out of balance due to muscle ‘drop’.

What is the 12 thoracic nerve called?

One of the spinal nerves in the thoracic segment is called the thoracic spinal nerve 12 (T12). spinal nerves in the spinal cord. It comes from the spinal column, specifically at the level of thoracic vertebra 12 (T12). It is also referred to as the “subcostal nerve.”

Why is the long thoracic nerve called the nerve of Bell?

The top portion of the superior trunk of the brachial plexus gives rise to the long thoracic nerve, also known as the external respiratory nerve of Bell or the posterior thoracic nerve. This nerve normally receives support from cervical nerve roots C5, C6, and C7.

References

- Lung, K. (2023, July 24). Anatomy, Thorax, Long Thoracic Nerve. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535396/

- Sendić, G. (2022, December 5). Long thoracic nerve. Kenhub. https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/long-thoracic-nerve

- Long Thoracic Nerve. (n.d.). Physiopedia. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Long_Thoracic_Nerve

2 Comments