Mirror Therapy

Introduction

In mirror therapy (MT), a mirror is used to create a reflective illusion of an affected limb to trick the brain into thinking movement has occurred without pain, or to create positive visual feedback of a limb movement. It affects placing the manufactured limb behind a mirror.

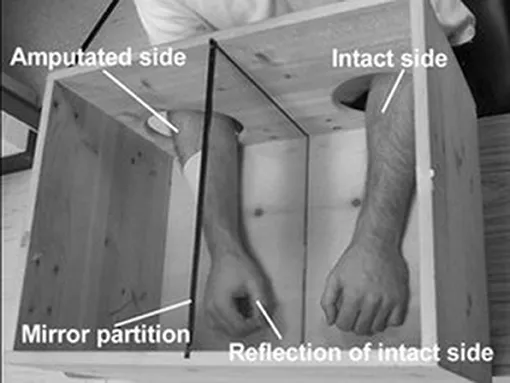

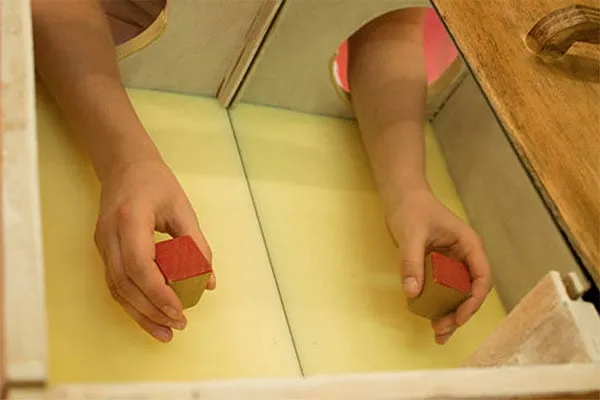

The mirror is positioned so the consideration of the opposing limb appears in place of the hidden limb. Clinicians can also create this delusion with a mirror box. This device is simply a box with a mirror in the center that permits the hands to be placed on either side of the mirror. The affected limb is always covered while the unaffected limb is placed on another side so its reflection can be seen in the mirror.

Mirror therapy (MT) or mirror visual feedback (MVF) is a restorative for pain or disability that involves one side of the patient more than the other side. It was invented by Vilayanur S. Ramachandran to engage post-amputation patients who had phantom limb pain (PLP). Ramachandran completed a visual (and psychological) illusion of two entire limbs by putting the patient’s affected limb into a “mirror box,” with a mirror down the center (encountering toward a patient’s intact limb).

The patient then glimpses into the mirror on the side with the good limb and makes “mirror symmetric” activities, as a symphony conductor might, or as a person does when they clap their hands. The pursuit is for the patient to imagine regaining control over a missing limb. Because the problem is seeing the reflected image of the good limb moving, it seems as if the phantom limb is also moving. Through the utilization of this artificial visual feedback, it becomes feasible for the patient to “move” the phantom limb and unclench it from potentially unfortunate positions.

Mirror therapy has expanded outside its origin in treating phantom limb pain to the treatment of other kinds of one-sided pain or disability, for representative, hemiparesis in post-stroke patients and/or limb aches in patients with Causalgia (complex regional pain syndrome).

Background of Mirror Therapy

Mirror therapy was first presented as a potential therapeutic intervention by Vilayanur S. Ramachandran to assist alleviate Phantom limb pain, a condition in which patients feel they still have pain in the limb after amputation.

Ramachandran and Rogers-Ramachandra first developed the technique in an attempt to assist those with phantom limb pain resolve what they termed a ‘learned paralysis’ of the painful phantom limb. The visual feedback, regarding the reflection of the intact limb in place of the phantom limb, made it possible for the patient to perceive movement in the phantom limb.

They hypothesized that every time the patient attempted to drive the paralyzed limb, they received sensory feedback (through vision and proprioception) that the limb did not drive. This feedback forged itself into the brain circuitry through a process of Hebbian learning, so that, even when the limb was no longer present, the brain had learned that the limb (and subsequent phantom) was paralyzed. To retrain the brain, and thereby eradicate the learned paralysis, Ramachandran and Rogers-Ramachandran created the mirror box. You can also read more about mirror therapy through Stephen Sumner’s experience who lost his limb some years ago.

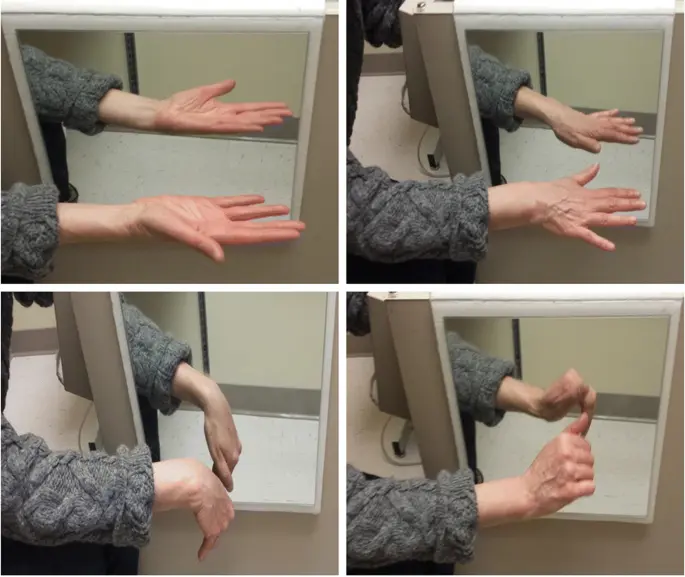

The technique of Mirror Therapy

The patient places the unaffected limb on one side, and the stump on the other. The patient then looks into the mirror on the side with an unaffected limb and makes “mirror symmetric” movements, as a music conductor might, or as we do when we clap our hands. Because the subject is noticing the reflected image of the good hand moving, it appears as if the phantom limb is also moving. Through the use of this artificial visual feedback, it becomes possible for the patient to “move” the phantom limb, and unclench it from potentially painful positions.

Graded Motor Imagery: Mirror Therapy Explanation and Stages

Mirror Therapy, one of the actions of Graded Motor Imagery (GMI), is a relatively new approach to treating phantom limb pain. GMI can also assist with the control of a myoelectric prosthetic appliance for those with an upper limb amputation. All the steps of Graded Motor Imagery depended on the neurology of the brain and its capability to change and adapt. The steps are:

- Laterality Reconstruction (left or right discrimination exercises)

- Motor Imagery

- Mirror Therapy

Mirror Therapy concerns viewing the unaffected limb in a mirror while keeping the residual limb out of sight. To begin, someone observes the sound limb in the mirror, and then gradually begins to move the hand while persisting to watch in the mirror. These actions can also cause the brain to “re-think” the pain reaction that it has been experiencing since the amputation and embrace the image of the healthy hand in place of the injured limb. The phrase “seeing is believing,” is sometimes dramatically presented by a sudden pain reduction of the affected limb. Yet, most times this technique requires an ongoing responsibility of 10 to 20 minutes several times per day to be effective.

We are including the steps beneath to give you an idea of what mirror therapy looks like, but the first several sessions should be performed with the assistance of a professional clinical therapy professional directing you through the steps. If you are examining for a therapist to work with, please contact us. It is not distinctive to participate in an unexpected emotional reaction when trying mirror therapy. A therapist can also assist you in navigating those feelings as well, and assist you in discovering additional support if needed.

Mirror Therapy

- Execute the exercises in a quiet room, ideally at the same time of day and in the same location.

- Sit, stand or lie down in a relaxed, supported position so that you can also concentrate without having to pay attention to your posture or position.

- Utilize a mirror box or place the side of a mirror against your chest so that the reflective side faces your unaffected hand or arm and your affected hand/arm is hidden behind the mirror.

- Bend forward so that you can also see the reflection of your unaffected arm in the mirror. Explore the reflected arm for several minutes without moving and imagine the reflection to be your affected hand/arm in its previous intact state.

- Start to slowly move your unaffected arm while looking at the reflection and keeping the affected arm relaxed. Again, imagine that the reflection of the moving limb is your affected hand/arm in its previous intact state.

- Next activity both the unaffected and affected arm simultaneously while concentrating on the reflected arm and imagining it to be your affected arm moving in a normal way.

Begin with simple, non-painful movements. Simple movements may also contain turning your palm up and down, making a fist, flattening the hand, moving each finger, touching your thumb to each finger, tapping fingers on a surface, and then progressing to more complex tasks such as drawing the alphabet with a finger in the air, writing, cutting, using tools, etc.

Consider such movements as opening your hand to permit a butterfly to fly away, dropping stones in a river, or throwing a ball. Do not do any activities that deliver pain in your phantom limb. It may be helpful at some point to touch your face with your unaffected hand while making the same movement with your affected arm.

Accomplish Mirror Therapy three to five times per day. Originally, you may only be able to observe the image of the mirrored hand and perhaps make small movements. With time, try to make more extensive and smoother movements with both arms. Your initial sessions may be quite short (two to three minutes), but gradually improve the duration of each session. Once the movements feel quite easy, do the exercises in different situations such as in a noisy room, when you are hot, when you are tired, when you are not in a good mood, etc. Again, please reach out to us if you are looking for a therapist to help you begin your work with Mirror Therapy. If you have forced Mirror Therapy and would want to tell your peers about your knowledge of it, please leave a comment below.

Principle of Mirror Therapy

- This approach exploits the brain’s preference to prioritize visual feedback over somatosensory/proprioceptive feedback concerning limb position. In disorders such as phantom limb pain (PLP), stroke, or Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type 1 (CRPS1) where neuropathic processes cause problems with pain, related or unrelated to movement, this approach is thought to present potential relief.

- Mirror therapy has been shown to improve cortical and spinal motor excitability, possibly through the effect on the mirror neuron system. Mirror neurons account for about 20% of all the neurons attending in the human brain. These mirror neurons are accountable for laterality reconstruction i.e., the ability to distinguish between the left and the right side.

- When utilizing the mirror box, these mirror neurons get activated, which assists in the recovery of affected parts. This system is thought to utilize the observation of movement to stimulate the motor processes which would be concerned with that movement. Similarities have been drawn with motor imagery whereby the individual will mentally imagine movements rather than observe the reflection of a movement in a mirror.

- Yet, the neuronal mechanisms behind mirror therapy and motor imagery have been suggested to be distinct. It is thought that the brain’s natural inclination to prioritize visual feedback over all others would make mirror therapy a more powerful tool. Regardless, analysis evidence is currently lacking in support of this hypothesis. It is to be noted that the major difference in the neuronal reorganization while using a mirror box is that the ipsilateral hemisphere’s neurons give connection to the same-side affected limbs rather than conventional therapies which mark the neuronal reorganization of the contralateral hemisphere.

What Is Mirror Therapy?

Mirror therapy is a restorative intervention first introduced to assist relieve phantom limb pain, which occurs when a person experiences pain in their amputated limb. It involves utilizing a tabletop mirror to create a reflection of your arm or hand. The mirror is placed in the middle of the body, hiding the affected side and encountering the non-affected side, so that the non-affected side appears in the reflection.

Then, someone utilizes the non-affected arm to perform various arm and hand exercises while watching the reflection in the mirror. Rehearsing movements with your non-affected limb while watching its mirror image (which appears to be your affected limb) moving to assist in “tricking” the brain into thinking that you are moving your affected arm even though you aren’t.

In amputees, numerous sessions of mirror therapy were found to decrease phantom pain by assisting the brain to recognize and “feel” the amputated limb. As the applications of mirror therapy extended, similar effects were also seen in individuals with pain and/or sensation deficits post-stroke. Similarly, researchers found that mirror therapy is especially effective in helping to enhance movement in the affected limb(s) of stroke survivors.

How Does Mirror Therapy Work?

To sufficiently understand how this phenomenon works, researchers focused on two concepts: mirror neurons (Neurons (nerve cells) are activated both when someone performs an action and watches someone else perform the same action) and neuroplasticity. The brain’s capability to reorganize its structure throughout a person’s life. Mirror neurons are neurons in the brain that are activated when you execute a task but are also activated when you look at someone else performing this task. Yet, these mirror neurons are only started if you watch an action that you can perform yourself.

- For representative, mirror neurons are not activated if you look at a bird flying. What is more surprising is those mirror neurons are also activated when an individual is imagining an action but not performing it! This is also why you may also sometimes discern what other individuals feel: if you see someone get his fingers caught in a door, you will presumably “feel” that person’s pain, and wince. The brain is not a determined network of neurons set in a given arrangement for life, like an old electrical board. The brain is continuously trying to find more profitable ways to deliver and deal with details by creating or removing connections between neurons. This spectacle of neural changes is called neuroplasticity.

- When babies are discovering the world close to them with their five senses, their brains undergo intense development and remodeling. Subsequently, when children learn to ride a bike, catch a ball, or play a musical instrument, more remodeling occurs, permitting the child to perform complicated actions without actually thinking about every step involved. When detecting a ball that is flying toward you, you do not intentionally think of using specific muscles at precise times, you just catch the ball, because your brain already comprehends which muscles must be activated and when. Neuroplasticity continues to take place during a person’s entire life and may also have lasting effects depending on your experience in a given activity: this is why, for instance, the more you train in mental calculation, the more intelligent and fast you evolve.

- If a specific region of the brain is damaged (from a stroke, disease, or trauma from an accident), that brain area can no longer send specific commands to the body. Yet, because neuroplasticity allows the brain to modify its organization, some individuals with brain damage can still regain some of their movements, thanks to the creation of new connections between neurons. These new connections offer new ways to send details, the same way a new bridge permits individuals to cross a river when the old bridge has collapsed. Prevalent, being young is a strong benefit in recovering movement after a brain injury, because neuroplasticity is at its peak when the brain is still developing. The younger you are, the sufficiently you can recover.

Now that you have uncovered a small about neuroplasticity, you may better understand how mirror therapy works to reduce unpleasant phantom limb sensations: the visual system tells the mirror neurons that the phantom limb is pushing (even though it is not). With training and a little patience, assisting the brain to “see” and “feel” the amputated limb move may also change the way the brain deals with signals, by eliminating the older negative feedback (“the phantom limb is not moving”) and establishing new connections to “feel” the limb again.

Can We Make a Better Mirror Therapy?

Mirror therapy has been stretched and has shown promising consequences for the treatment of other health problems, including chronic pain, re-education of the brain after stroke, and even arthritis. Yet, the usage of mirror therapy is still very limited and much remains to be done to enhance this therapy and its use. While traditional mirror therapy only permits small movements and cannot provide a truly natural experience to fool the brain and give it the fantasy of movement, the new technology of virtual reality

An artificial environment, created with a computer and software presents users with a situation they can interact with (see, hear, touch, grab, etc.). The representations can also be so convincing that participants accept the environment as real. (VR) delivers just that. VR gives a person the fantasy of movement by dropping them in a three-dimensional environment and giving them an avatar, or the appearance of a body. With VR, individuals can interact in an environment generated by a computer, as if they were in a video game! Unlike traditional mirror therapy, VR offers the delusion of movement for body parts that do not come in pairs, like the head, for example.

A team of researchers just asked people immersed in VR to turn their heads to the side but manipulated what they were seeing, making them think they moved their leaders more than they did. When the people were then asked to say how much their heads moved, they always overestimated the movement. As illustrated, their perceived movement was influenced by incorrect visual information that overpowered the actual feeling of the activities themselves—they were tricked by the VR experience!

When the party was asked to move his head, the virtual head movement he saw through the VR viewer was exaggerated in the virtual world, it showed him pushing his head more than he did. Though he only turned his head to the dashed line, he thought he rotated his head to the solid line. The VR world can fool the brain into feeling more movement than occurs. Image from Harvie et al.

Another issue with traditional mirror therapy is that it cannot always be used to assist individuals with amputated legs to walk again, or to decrease their pain. An AVR version of mirror therapy was created to assist with this. A person with a prosthetic leg was shown an avatar of himself in which his missing leg looked like a normal leg. For the player, it was as if he was walking with two real legs. Over time, the slight asymmetry in his walk progressively decreased and his limp almost disappeared.

Mirror Therapy for various conditions

Mirror Therapy In Stroke Patients

Mirror therapy (MT) has been employed with little success in treating stroke patients for pain as well as motor function. Clinical investigations that have integrated mirror therapy with conventional rehabilitation have achieved the most positive outcomes. Yet, there is no evident consensus as to its effectiveness. In a current survey of the published research, Rothgangel et al. extrapolated that: “In stroke patients, we found a moderate feature of evidence that mirror therapy as an additional therapy, enhances recovery of arm function after stroke. The grade of evidence concerning the consequences of mirror therapy on the recovery of lower limb functions is still low, with only one study documenting its effects. In patients with CRPS and PLP, the differentia of evidence is also low.”

A current Cochrane Review summarised the effectiveness of mirror therapy for enhancing motor function, activities of daily living, pain, and visuospatial neglect in patients after stroke. 14 investigations with a total of 567 participants that corresponded mirror therapy with other interventions were compared. At the end of treatment, mirror therapy improved the activities of the affected limb and the capability to carry out daily activities, it decreased pain after stroke, but only in patients with a complex regional pain syndrome, and the advantageous effects on movement were maintained for six months, but not in all study groups.

Treatment with mirror therapy soon expanded beyond its origin in treating phantom limb pain to the treatment of other kinds of one-sided pain and loss of motor control, for example in stroke patients with hemiparesis. In 1999 Ramachandran and Eric Altschuler extended the mirror technique from amputees to enhance the muscle control of stroke patients with weakened limbs. A critique article published in 2016 concluded that “Mirror therapy (MT) is a valuable method for improving motor recovery in poststroke hemiparesis.”

According to a 2017 examination of fifteen studies that compared mirror therapy to conventional rehabilitation for the recovery of upper-limb function in stroke survivors, mirror therapy was more prosperous than CR in promoting recovery. A 2018 review established on 1685 patients recovering from hemiplegic stroke found mirror therapy provided effective pain relief while enhancing motor functions and activities of daily living (ADL). Thirteen out of seventeen randomized controlled difficulties found that mirror therapy was beneficial for post-stroke patients’ legs and feet, according to a 2019 review paper. Despite significant research, as of 2016 the underlying neural mechanisms of mirror therapy (MT) for stroke were still unclear. As Deconick et al. state in a 2014 review, the mechanism of enhanced motor control may vary from the mechanism of pain relief.

The Importance of Neuroplasticity for Stroke Recovery

- One of the major reasons that mirror therapy outcomes is due to mirror neurons. These are nerve cells that are triggered by performing a movement or by simply watching a movement occur. Mirror therapy supplies the visual feedback necessary to assist mirror neurons’ fire by simply seeing the movement. Consequently, your brain gets the feedback necessary to flash the rewiring process called neuroplasticity.

- Neuroplasticity is the brain’s capability to heal and rewire itself after a neurological injury like a stroke. It is best activated through increased repetition of therapeutic exercises, or massed practice. Neuroplasticity strengthens existing neural pathways (connections) and constructs new ones. The more vigorous the neural pathways for a specific function become, the higher the chances of restoring that function.

- After a stroke, many neural pathways become impaired or destroyed. Depending on the area(s) of the brain impacted by stroke, specific functions may become impaired. Fortunately, neuroplasticity permits healthy parts of the brain to take over lost functions. For instance, when the brain has a problem sending signals to the hand after a stroke, neuroplasticity authorizes new areas of the brain to take overhand function.

- Mirror therapy is a better way to activate neuroplasticity, as it repetitively activates mirror neurons involved in affected movements. For instance, consistently practicing specific movements, such as hand therapy exercises, during mirror therapy can also assist the brain to rewire itself and strengthen the pathways that control hand function. Therefore, mirror therapy may also help activate neuroplasticity and promote overall recovery.

Mirror Therapy in Complex Regional Pain Syndromes

Working with patients with various complex regional pain syndromes can also be challenging. Pharmacological therapies are frequently associated with a variety of side effects. Mind-body modalities are thought to recreate a role. Mirror therapy triggers neuroplasticity by improving the relationship between neurons in the brain and thereby enhances communication between the motor and the sensory cortex.

Recent investigations have shown the favorable effects of mirror therapy in patients with CRPS Type 1 disease. Nevertheless, the lack of clear consensus and a large body of clinical experience makes it hard to supply good evidence-based guidance to most of our chronic pain patients. Current evidence supports the usage of Mirror Box Therapy.

Post-amputation phantom limb pain

Depending on the observation that phantom limb patients were much more likely to commentary paralyzed and painful phantoms if the actual limb had been paralyzed before amputation (for instance, due to a brachial plexus avulsion), Ramachandran and Rogers-Ramachandran suggested the “learned paralysis” hypothesis of painful phantom limbs.

They hypothesized that every time the patient attempted to move the paralyzed limb, they obtained sensory feedback (through vision and proprioception) that the limb did not move. This feedback forged itself into the brain circuitry via a procedure of Hebbian learning so that, even when the limb was no longer present, the brain had comprehended that the limb (and succeeding phantom) was paralyzed.

Ramachandran satisfied the mirror box to reduce pain by assisting an amputee in imagining motor control over a missing limb. Mirror therapy is now also widely utilized for the treatment of motor disorders such as hemiplegia or cerebral palsy. As Deconick et al. state in a 2014 study, the mechanism of motor control and pain relief may differ from the mechanism of pain relief. Deconick et al., who reviewed only the effects of MVF on sensorimotor control, found that MVF can also wield a strong influence on the motor network, particularly through increased cognitive penetration in action control.

Although there has been much analysis on MVF, authors of many review articles complain about the poor methodology constantly utilized, for instance, tiny sample sizes or lack of control groups. For this reason, one 2016 investigation (based on a review of 8 studies) supposed that the level of evidence was insufficient to suggest mirror therapy as a first-intention treatment for phantom limb pain. A 2018 review, (based on 15 investigations conducted between 2012 and 2017, out of a pool of 115 publications) also condemned the quality of many statements on mirror therapy (MT) but concluded that “MT occurs to be sufficient in facilitating PLP, reducing the intensity and duration of daily pain episodes. It is a valid, straightforward, and inexpensive treatment for PLP.” A 2018 publications examination of phantom limb pain stated that, in randomized controlled trials, mirror therapy decreased pain.

Conclusion

Traditional mirror box therapy has been demonstrated to be a very simple and interesting method to assist with the phantom limb phenomenon. Nevertheless, the utilization of mirror therapy is limited to simple movements affecting a single arm or leg. Because of this limitation, we have diverted to new strategies and technologies. VR has shown promise in this domain and has become more than merely a tool for gaming and entertainment. VR has many benefits, including the ability to create realistic, interactive, and modifiable environments to preoccupy the brain from the other senses. Likewise, VR allows scientists to contain other senses into the experience, like hearing or touch. VR could be used, for instance, to design serious games

A play that has been designed for a pursuit other than pure entertainment: pedagogy, education, reeducation, etc. for the management of patients suffering from phantom limb syndrome or other limitations of movement. In determination, tricking the brain through VR is a promising new technology for assisting the brain to adapt to the challenges posed by amputations or other harms affecting the movements of the body. MT is a non-pharmacological and alternative therapy strategy that has been proposed as a means of managing phantom limb pain (PLP). It is a neuro-rehabilitation technique designed to demodulate cortical mechanisms. With this approach, patients perform movements utilizing the unaffected limb whilst watching its mirror reflection superimposed over the (unseen) affected limb. This completes a visual illusion and provides positive feedback to the motor cortex that movement of the affected limb has occurred. The procedure is thought to offer potential relief through the visual dominance of motor and sensory processes.

Regarding the importance of PLP and its management, mirror therapy offers clinicians an easy-to-use and low-cost adjuvant therapeutic technique. Yet, its effectiveness as a stand-alone modality largely arises from low-quality evidence. Rather, there is a greater weight of evidence in favor of its use as a combined or sequential therapy, such as Graded Motor Imagery.

FAQ

What is mirror therapy good for?

Mirror therapy is used to enhance motor function after a stroke. During mirror therapy, a mirror is positioned in the person’s midsagittal plane, thus reflecting movements of the non‐paretic side as if it were the affected side.

What does mirror therapy do to the brain?

Mirror therapy is a kind of therapy that employs vision to treat the pain that people with amputated limbs sometimes feel in their missing limbs. Mirror therapy does this by tricking the brain: it gives the misconception that the missing limb is moving, as somebody looks at the real, remaining limb in a mirror.

How often should you do mirror therapy?

Follow the instructions below 4 to 5 times a day (or as directed) but only use the mirror for brief periods (maximum 10 minutes) or until you feel you are no longer able to concentrate. It is best to utilize it a little and often.

Do mirrors help anxiety?

According to a 2016 study that she authored, looking in the mirror to be kind to oneself can decrease levels of anxiety and stress and we know de-stressing can also have a multitude of uses, ranging from better sleep to improved skin health.

Is mirror therapy evidence based?

Mirror therapy (MT) has been employed with some success in ministering to stroke patients for pain as well as motor function. Clinical investigations that have integrated mirror therapy with conventional rehabilitation have gained the most positive outcomes. Nevertheless, there is no clear consensus as to its effectiveness.

How do mirror neurons affect emotions?

As it turns out, our mirror neurons fire when we participate in emotion and similarly when we see others experiencing an emotion, such as happiness, fear, anger, or sadness. When we see an individual being sad, for instance, our mirror neurons fire and that allows us to experience the same sadness and to feel empathy.

How effective is mirror work?

Approaches rooted in psychology and neuroscience also point to mirrors aiding in self-development, shifting the way you see yourself, and grounding you in your body. Other possible benefits of mirror work? An improved sense of self-confidence, inner peace, and a deeper sense of trust in yourself and your life.

4 Comments