Radius Bone Fracture

Introduction

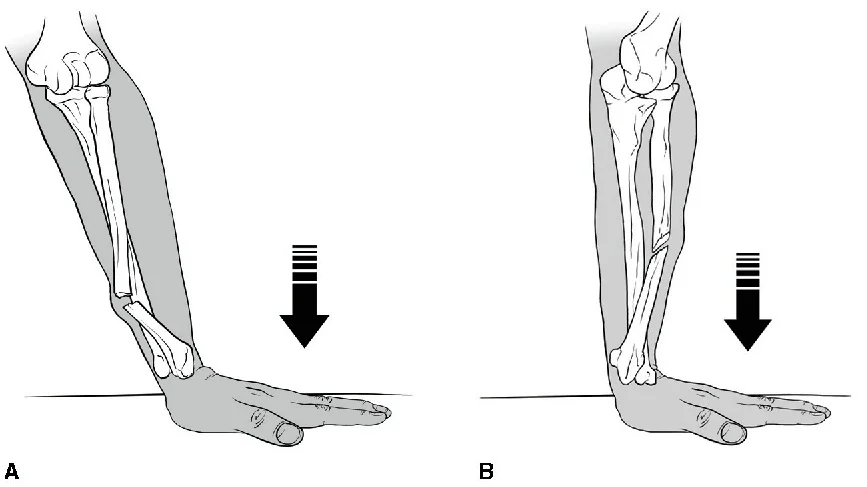

Distal fractures are more prevalent than proximal fractures in fractures of the radius, which are the most common fractures of the upper extremities. The most frequent way that a radius fracture occurs is from falling onto an outstretched hand.

Anatomy

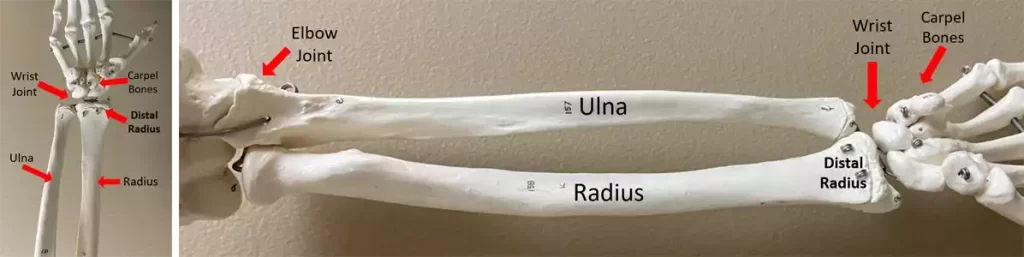

One of the two bones in the forearm is the radius. Ulna is the other. On the lateral (thumb) side of the forearm, the radius is opposite the ulna. When you extend your arm straight out in front of you, palms down, the radius rotates over the ulna. When you hold your arms straight out and place your palms facing up, they are more parallel to one another.

One of the longest bones in your body, the radius is the third longest bone in your arm. The radius bones of most adults are about 10 inches long.

Your radius consists of three parts: a long, slightly curved shaft in the middle, a little end where it meets your humerus (upper arm bone), and a larger end where it hits your wrist. Compared to your ulna, it is somewhat shorter and thicker.

Radius proximal aspect

Your humerus is connected to the higher (proximal) end of your radius. What’s at the proximal end (aspect) is the:

- Head.

- Neck.

- Radial tuberosity.

Radius shaft

The long, central section of the radius, known as the shaft, gives your forearm its shape and supports its weight.

Radius distal aspect

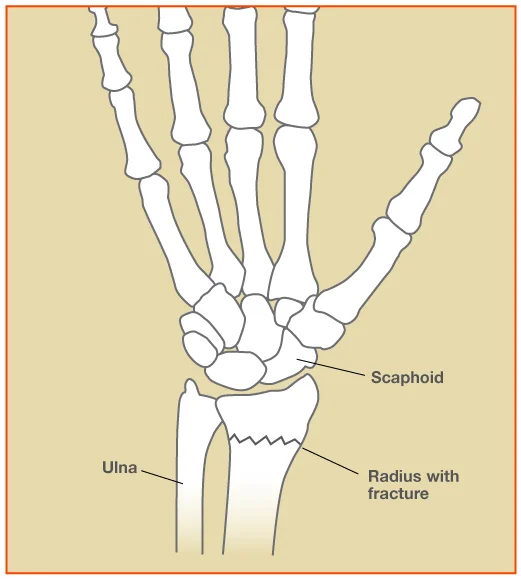

The top of your wrist joint is formed by the lower (distal) end of your radius. Where it joins the lunate (the wrist or carpal bones) and scaphoid, it is wider than the remainder of your radius. At the radius’s distal end are the following:

- Styloid process.

- Ulnar notch.

Radius Fracture

Nearly invariably, a distal radius fracture happens one inch from the bone’s end. For individuals of all ages, this common fracture can manifest in a variety of ways. These fractures usually happen in young people as a result of high-energy incidents like car crashes or falls from ladders. A simple fall onto the wrist can result in distal radius fractures in older adults, particularly in those with osteoporosis.

Any radius fracture that happens at the wrist is referred to as a “distal radial fracture.” This designation is misleading because there are various kinds of DR fractures. They can all have distinct presentations, distinct mechanisms of harm, and distinct approaches to care. Understanding the fundamental care and urgent referral criteria for every kind of DR fracture is crucial.

Colles’, and Smith’s, Isolated Radial Shaft Fractures, Both Bone Fractures -The most frequent fracture of the distal radius in adults is called a Colles’ fracture. The Irish surgeon Dr. Abraham Colles, who first documented this pattern of injuries in 1814, is credited with giving it its name. The traditional FOOSH is the mechanism of harm. The fracture, which is a metaphyseal fracture, happens about 1.5 inches in front of the carpal joint. It typically manifests as displacement of the distal fragment of the radius and dorsal angulation. The wrist deformity known as the “dinner-fork” deformity will show up on an X-ray. In essence, the Smith’s fracture is the opposite of the Colles’ fracture. The term “reverse Colles” is frequently used to describe it, and it happens when the dorsum of the hand is struck directly or falls on it.

The distal fragment of the Smith’s fracture will angulate volarly, in contrast to the Colle’s fracture. This damage results in an X-ray distortion called a “garden spade.” While Smith’s and Colles’ fractures frequently happen alone, they can also be accompanied by other traumas. Fractures of the isolated radial shaft can happen anywhere along the bone.

Isolated distal third radial shaft fractures have a similar mechanism of injury to those caused by Smith’s and Colles’ fractures, and they are frequently treated similarly. Forearm fractures involving both bones are relatively frequent, particularly in young people. Usually, a “fall from height” causes them. Both the ulna and radius are affected by these bone fractures. Still, the distal radius is often affected. With this pattern of injuries, open fractures occur frequently.

Chauffeur’s/Radial Styloid Fracture – The radial styloid is a part of the intra-articular radius fracture known as the Chauffeur’s fracture. The size of the fracture fragment may vary. A hit to the rear of the wrist that causes dorsiflexion and abduction, causing the scaphoid to compress on the radial styloid, is frequently the cause of the injury, also known as a FOOSH injury. Patients may have minor, clinically insignificant radial styloid avulsions; nonetheless, these injuries are frequently linked to disruption of the radioscaphocapitate and other collateral ligaments, which can result in scapholunate disruption and lunate dislocation. In the past, drivers who had to use a hand crank to start their cars would sustain these fractures.

Die-Punch Fracture -An intra-articular fracture affecting the radius’ lunate facet is known as a die-punch fracture. One of the distal radius’s three articular surfaces is the lunate facet. It is situated between the scaphoid facet and the ulnar articulation. It joins the lunate bone in the wrist to the distal radius. When the lunate is loaded axially, an impaction fracture to the lunate facet of the radius results in a die-punch fracture. Although it commonly happens on its own, this fracture may cause other ailments as well.

Galeazzi Fracture-Dislocation -A distal third of the radius fracture combined with a distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) dislocation is known as a Galeazzi fracture-dislocation. Usually, FOOSH injuries result in these fractures. It is a rare pattern of injury, and doctors may overlook the DRUJ component. The ulnar displacement is used to determine their labeling. For instance, a “Volar Galeazzi” occurs when the DRUJ disruption results in the ulna’s volar deviation.

Barton’s Fracture -An intra-articular rim fracture of the distal radius is known as Barton’s fracture. Dorsal or volar classifications are both possible for it. Forced dorsiflexion and pronation lead to more frequent dorsal rim fractures. Falls that land on a supinated hand or wrist frequently result in volar rim fractures. These stresses cause the radial rim to avulsion fracture as a result of the radiocarpal ligaments being damaged. The avulsed piece migrates dorsally in dorsal fractures. With volar fractures, the situation is the opposite. These fractures are unstable and frequently cause the carpal bones to dislocate.

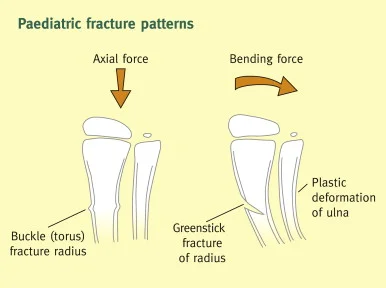

Greenstick and Buckle/Torus Fractures -Greenstick and torus fractures are examples of incomplete fractures. Compared to adult bones, pediatric bones have less mineralization and are pliable enough to bend without cracking. Although they can happen in any long bone, the distal radius’s metaphysis is where they most commonly happen. Greenstick fractures are caused by bending forces, whereas torque fractures are caused by axial stress. The periosteum and bone cortex will buckle in torus fractures, but there won’t be any visible fracture lines. Torus fractures typically result in little deformity and healthy periosteum and cortex. Bony bending will be evident in greenstick fractures. The convex surface will fracture while the concave surface remains intact. Children get these fractures a lot, but sadly, they are usually overlooked.

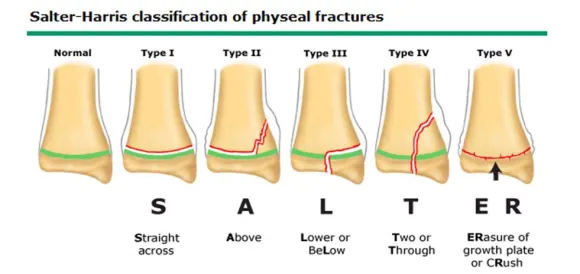

Salter-Harris Type Fractures – A pediatric fracture involving the epiphyseal plate is called a Salter-Harris fracture. Although they can happen in any bone with a growth plate, the distal radius is the most common location for these fractures. The most widely used classification model for epiphyseal fractures was initially created in 1963 by physicians William Harris and Robert Salter. Grades I through IX are used for Salter-Harris fractures, with grades I through V being the most commonly utilized in clinical practice. A transverse fracture through the growth plate is called a type I fracture. Type II passes via the metaphysis and growth plate. Type III affects epiphysis and the development plate. A type IV fracture involves the growth plate, metaphysis, and epiphysis. A growth plate fracture with total direct compression is known as type V. Each of these has a unique management plan and prognosis.

The distal radius can also fracture in the following ways:

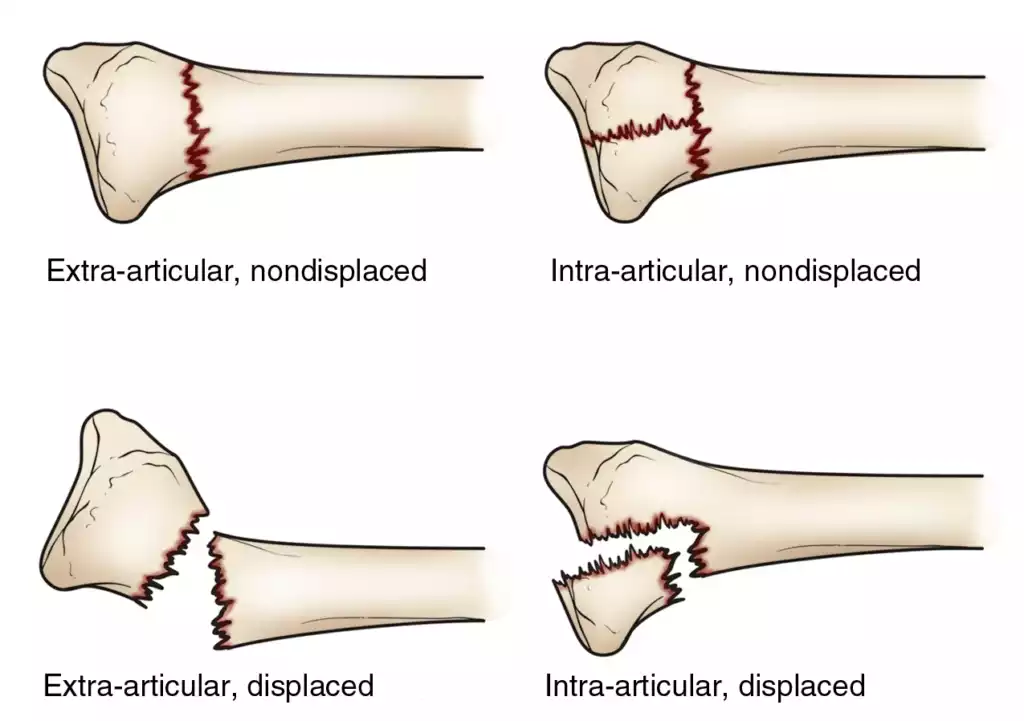

- Intra-articular fracture — The wrist joint is affected by an intra-articular fracture. (“Articular” denotes “joint.”

- Extra-articular fracture —An extra-articular fracture occurs when a fracture does not go into the joint.

- Open fracture —An open fracture occurs when a broken bone exposes the skin. The risk of infection with these fractures necessitates prompt medical treatment.

- Comminuted fracture — A fracture that breaks a bone into more than two pieces is referred to as a comminuted fracture.

It is crucial to identify the kind of fracture since some are easier to treat than others, such as intra-articular fractures, open fractures, comminuted fractures, and displaced fractures(when the fragmented bone fragments are not perfectly aligned).

Causes

Accidents involving falling onto an extended arm are the most frequent cause of distal radius fractures.

A relatively slight fall can result in a broken wrist if an individual with osteoporosis, an illness common in older persons, has osteoporosis. Falls from standing are a common cause of distal radius fractures in adults over 60.

If the intensity of the trauma is great enough, a broken wrist can occur even in bones that are otherwise healthy. For instance, a young, healthy person may sustain a broken wrist in a car accident or a fall off a bike.

In elderly patients, good bone health may be able to prevent fractures. Individuals who have a family history of osteoporosis should discuss bone-strengthening treatments with their primary care physician.

The majority of distal radius fractures happen to individuals over 50 and children under 18. An osteoporosis-affected older adult may fracture from a relatively minor fall. Younger individuals frequently suffer fractures to their wrists when they fall while doing sports, such as:

- Snowboarding

- Soccer

- Football

- Cycling

After hip fractures, distal radius fractures are the second most common trusted fracture in those over 65.

Numerous variables can be identified as the direct causes of a distal radius fracture:

- Falls. A distal radius fracture is most frequently caused by a severe fall onto an extended arm. This kind of fall might happen while going about your regular business or participating in sports.

- Bone disorders. People with bone disorders like osteoporosis are more prone to breaking their wrists in even small falls. This illness weakens and renders the bones in the body particularly fragile, making a person more prone to fractures of this kind. Research and studies in medicine have demonstrated that a direct strike to the wrist can result in a fracture of the distal radius bone or wrist fracture. Even in people with apparently healthy bones, the impact of the hit can cause the wrist bone to shift.

- Age. These kinds of injuries might also be attributed to age. Distal radius fractures are more common in people sixty years of age and older than in other age groups. Weak bones or other medical conditions are the cause of fractures in the elderly. Women going through menopause, those with poor diets, and those who use illegal drugs may lose muscle mass, which increases their risk of wrist fractures.

Risk Factors

The development of a distal radius fracture is frequently associated with age, gender, and health problems.

Osteoporosis is the primary cause of distal radius fractures in adults over 60, especially in cases when the fall was relatively small, like a fall from a standing position. If the damage is severe enough—for example, from a vehicle accident or a fall off a bike—they can occur even in healthy bones.

Age

- Throughout life, the incidence of distal radius fractures has a bimodal distribution.

- Incidence is highest in the pediatric population, declines in young adulthood and middle age, and then rises once more in the elderly.

Gender

- In the pediatric population, the gender distribution curves for DRF incidence show that boys are more likely than girls to get DRF.

- Men aged 19–49 had higher DRF than women of the same age, a gender disparity that persists until middle adulthood.

- After that age, the incidence of DRF rises noticeably, putting women over 50 at 15% lifetime risk, while men’s incidence stays low until they are 80 years old.

- Around the world, older women continue to sustain injuries at a considerably higher rate than older men.

Health conditions

Distal radius fractures seem to happen less frequently in those who have severe dementia.

The following medical problems can lead to low bone quality:

- Persistent stroke

- The osteoporosis

- Diabetes

- RA

- Persistent renal illness

Sign & Symptoms

Signs of a major injury in this area are generally evident, as with most fractures. Even though some bone wrist fractures are more serious than others, excruciating pain is typically the first indication of a distal radius break.

Another sign of a broken wrist is edema. Sometimes the edema can develop so that moving the damaged hand or wrist becomes challenging or almost impossible. a tingling feeling in the fingertips or possible restrictions on the range of motion.

There can even be a physical sign of the fracture, depending on how severe it is. For example, your wrist may appear malformed if a bone shifts.

If you believe you may have suffered a wrist fracture, be sure to look for the following signs:

- Sharp, sudden wrist pain that sometimes coincides with the sound or feeling of a crack during a fall or accident

- Tenderness and swelling in the wrists that start immediately and develop worse

- Abnormality of the wrist or forearm. A Colles fracture, the most common type of distal radius fracture, results in a very noticeable symptom called the “dinner fork deformity.” When viewed from a side view, the wrist resembles an overturned fork.

- Numbness and/or immobility in the hand or wrist

- Unwillingness to grasp or squeeze objects

- Bruising on the forearm and wrist

Diagnosis

A distal radius fracture is often diagnosed by a doctor in three steps:

Patient history

The patient will be asked to describe their symptoms, their onset, and their triggers by the doctor.

Physical exam

We’ll check the wrist and forearm for discoloration or dislocation. If a patient is capable, doctors may also instruct them to do specific hand or wrist movements.

You might be able to postpone seeing a doctor until the next day if the injury is not very severe and the wrist is not malformed. A splint can protect the wrist. Until a physician can inspect the wrist, it is possible to apply an ice pack and elevate it.

Go right away to an urgent care facility or emergency room for additional treatment if the injury is extremely painful, the wrist is significantly malformed, or the fingers are numb or pallid.

Imaging

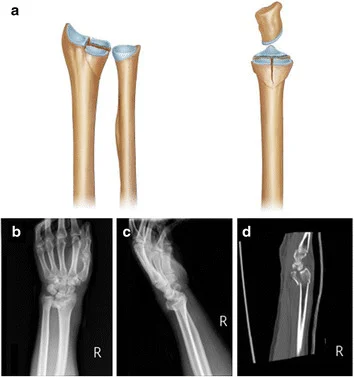

The physician will probably request wrist X-rays to confirm the diagnosis. X-rays can reveal displacement (a space between fractured bones) and whether the bone is broken. They can also display the number of fractured bone fragments.

The most accurate method for identifying a distal radius fracture is this one. Almost always, doctors will request an X-ray examination of the wrist taken from multiple perspectives. In some situations, they might additionally use alternative imaging techniques:

- To investigate complicated fractures or search for additional soft tissue damage nearby, an MRI or CT scan may be beneficial. To demonstrate injury to ligaments or other soft tissues, injected contrast dye may be used during MRIs and CT scans (referred to as MRI-arthrograms and CT-arthrograms).

- For otherwise difficult-to-see bone structures, a bone scan (scintigraphy) examination can identify metabolic changes in bone caused by fractures.

The physician could occasionally prescribe a computed tomography (CT) scan to get three-dimensional images of the fractured bone. This can support the planning of surgery.

The fracture’s classification will also be determined with the use of imaging. A distal radius fracture can be categorized in many ways, which may influence the course of treatment:

- What makes a fracture intra-articular versus extra-articular is whether or not it extends into the radiocarpal joint.

- If the bones or pieces have shifted, they are classified as either displaced or nondisplaced.

- Comminuted refers to a bone that has been broken or split into more than two pieces.

- Compound: if the skin has been damaged by the fracture

Treatment

Whether or not a fracture extends into the radiocarpal joint determines whether it is intra-articular or extra-articular.

The bones or parts are categorized as displaced or nondisplaced depending on how far they have moved.

A bone that has fractured or split into more than two pieces is referred to as comminuted.

Compound: if the fracture has caused injury to the skin

In any event, a splint is applied as soon as possible after a fracture to provide comfort and manage discomfort. Before the fracture is put in a splint, it is reduced, or returned to its original position, if it has been displaced. Local anesthetic is used during fracture reduction, so just the painful area is sedated.

Non-Surgical Treatment

Applying a splint or cast depends on how well the distal radius fracture is positioned. It frequently acts as a last resort till the bone recovers. A cast can stay on for up to six weeks on average. After that, you’ll receive a detachable wrist splint to wear for stability and comfort. You can begin physical therapy as soon as the cast is taken off to restore your wrists’ natural strength and function.

If the fracture is smaller or is deemed unstable, X-rays can be taken at three and six weeks. If the fracture is not lessened and is deemed to be stable, it could be taken less frequently.

First, a displaced fracture must be fixed. A plaster splint or cast is inserted once it has been anatomically adjusted. Usually, a local anesthetic is used to execute the reduction (closed reduction). After examining the fracture, your orthopedic physician will determine whether surgery is necessary or if a cast will be sufficient to treat the fracture for the next six weeks.

Rearranging the fractured bone fragments can be required if your arm’s future mobility is expected to be restricted due to the misaligned broken bone. The precise word for the procedure wherein the physician realigns the fractured pieces is reduction. A closed reduction is the process of straightening a bone without making an incision in the skin.

Your arm may be put in a cast or splint to maintain the alignment of the bones once they have been appropriately positioned. For the first several days, a splint is typically needed to accommodate some normal swelling. Usually, a cast is applied a few days to a week or so after the swelling subsides. Since the cast loosens as the edema decreases, it is usually changed two or three weeks later.

Your doctor may take routine X-rays to closely monitor the healing process, depending on the type of fracture. X-rays are frequently taken every week for three weeks and then again for six weeks in patients receiving non-surgical treatment. If the fracture was deemed stable and/or did not require reduction, X-rays can be obtained less frequently. Surgery could be suggested if the fracture ever becomes misaligned.

In non-operative fractures, the cast is usually taken off approximately six weeks following the fracture. At that point, physical therapy will probably begin to help your injured wrist heal and move more freely. To preserve the mending bone, you will usually wear a detachable splint in between therapy sessions.

Surgery for Distal Radius Fractures

This choice is typically reserved for fractures that are deemed unstable or for which a cast is not a suitable treatment. Usually, an incision is made across the volar portion of the wrist, which is where your pulse is felt, to perform surgery. This makes the break fully accessible. One or more plates and screws are used to assemble and secure the components.

To restore the anatomy, you might need to make a second incision on the back of your wrist in some circumstances. The parts will be secured in place with plates and screws. It might not be able to fixate the bone with plates and screws if there are several pieces. In these situations, the fracture may be secured with an external fixator, either with or without extra wires. The majority of the hardware on an external fixator stays outside the body.

Surgery is necessary if the displacement of the fracture is such that reduction is not enough to bring the bones into an appropriate position.

For healthy, active individuals with displaced distal radius articular fractures, orthopedic surgeons usually advise surgical treatment. The enormous number of solutions available for reduction and fixation is evident from the five Cochrane evaluations that have been published on this subject alone. Techniques consist of 1) dorsal plating; 2) bridging external fixation with or without further Kirschner-wire fixation; 3) closed reduction and percutaneous pinning, either extra- or intra-focal; 4) fragment-specific fixation, 5) utilizing a standard Henry technique for open reduction and internal fixation with a volar plate; 6) combining these techniques. Recurrent malunion, nonunion or delayed union, instability, tendon irritation or ruptures, osteoarthritis, residual ulnar-side pain, median neuropathy, complex regional pain syndrome, and issues with the bone-graft harvest site are among the surgical complications that can arise, according to Bushnell and Bynum (2007).

- External Fixation: Using tiny skin incisions, metal pins or screws are inserted into the bone using this closed, minimally invasive technique. After that, these pins can be fastened into an external fixator frame or fixed externally using a plaster cast. External fixation of distal radius fractures decreases displacement and produces better anatomical results when compared to a typical immobilization method. Nevertheless, there is currently little data to support external fixation’s improved functional results, and it carries a significant risk of consequences such as radial nerve damage and pin site infections.

- Internal Fixation: An open surgical procedure is required for internal fixation, exposing the fractured bone. T-plates, volar, or dorsal plates with screws can be employed. However, because open surgery is more intrusive and labor-intensive, there is a higher risk of infection and soft-tissue injury. For this reason, this kind of fixation is typically saved for more serious injuries.

- Bone Grafting: Bony voids are frequently present after the reduction of distal radial fractures, and they can be minimized by implanting bone grafts or bone graft replacements. Filler for lessening skeletal gaps can be made from autogenous bone taken from the patient or allogenous bone taken from cadavers or living donors. There is little proof that bone scaffolding would enhance anatomical or functional results, yet there is a chance of problems such as infection, nerve damage, or discomfort at the donor site. Except for closure wedge, most operations need bone grafting.

- Percutaneous Pinning: Another technique for reducing and stabilizing fractures is percutaneous pinning. It involves passing wires, threads, or pins into the bone through the skin. After the fracture is reduced, pins are frequently put into the bone to secure the distal radial fragment. This is a less invasive procedure. Since there are now no defined criteria for the best pinning technique or the level and length of immobility, the risk of complications likely outweighs the therapeutic benefits of pinning.

- Closed Reduction: When the arm is in traction, misplaced radial pieces are realigned utilizing various techniques in closed reduction. Various techniques include mechanical reduction, such as the use of “finger traps,” and manual reduction, in which two persons pull in opposite directions to create and sustain longitudinal traction. Nevertheless, there is not enough data to determine if the various closed reduction techniques used to treat distal radial fractures are beneficial.

- Arthroscopic-assisted reduction: The advantages of this method over open reduction are numerous. Not only is it less intrusive, but it also provides direct visibility, minimizes articular displacement, facilitates the diagnosis and treatment of related ligamentous injuries, removes articular cartilage debris, and lavages the radiocarpal joint. The main drawbacks of arthroscopic reduction are its lengthier and more complex technique, the scarcity of experienced surgeons, and the risk of compartment syndrome or acute carpal tunnel syndrome with fluid extravasation.

Procedure:

To access the shattered bone(s), surgery usually entails making an incision above the fracture on the wrist. Crucial anatomical features, such as arteries, nerves, and tendons, are recognized and safeguarded. Through the incision, the surgeon realigns the shattered bone or bones. Another name for this procedure is an open reduction.

Once the bone has been realigned, there are a few ways to keep it in place until it heals, depending on the type of fracture:

- To prevent infection, the exposed soft tissue and bone are carefully cleaned (debrided) and administered antibiotics.

- To keep the bones in place, external or internal fixation techniques are frequently employed.

- In case of severe injury to the soft tissues surrounding the fracture, your physician might use a temporary external fixator.

- A follow-up treatment a few days later, when the soft tissues surrounding the fracture are ready, may involve internal fixation with plates or screws.

You will wear a splint following the procedure for two weeks or until your first follow-up appointment. At that point, the splint will be taken off and replaced with a wrist splint that can be removed. It needs to be worn for four weeks. Following your initial clinic visit, you will begin your physical therapy to restore wrist strength and function. After your surgery, you can discontinue using the detachable splint after six weeks. You ought to keep performing the workouts that your therapist and surgeon have recommended. Getting moving right away after surgery is essential to a successful recovery.

Pain Management

Most fractures cause mild discomfort for a few days to several weeks. Many patients find that their discomfort can be effectively relieved by applying ice, elevating their arm over their heart, and using over-the-counter pain relievers.

To reduce pain and inflammation, your doctor could advise taking ibuprofen and acetaminophen together. When used together, the two drugs work far better than when taken alone. Your doctor might advise using a prescription drug, like an opioid, for a few days if the pain is really bad.

Though they can aid with post-operative pain relief, opioids are narcotics and can become dependent. Opioids should only be used as prescribed by your physician, and you should quit taking them as soon as your pain starts to subside. See your doctor if your discomfort does not start to go away a few days after your surgery.

Cast and Wound Care

Sometimes the original casts are replaced because the cast becomes loose due to the significant reduction in swelling. The final cast is often taken off for non-operative fractures after roughly six weeks.

Casts and splints need to be kept dry while they mend. When taking a shower, a plastic bag over the arm should be helpful. The cast will not dry quickly if it does get wet. A cool-setting hairdryer could be useful. If the cast gets wet, it frequently needs to be replaced.

For a minimum of five days, surgical incisions need to be kept dry and clean. After your operation, your doctor will advise you when it is safe to take off the bandages.

Potential Complications

You need to get your fingers back to full range of motion as soon as possible after surgery or casting. See your doctor for an evaluation if, within a day, pain and/or swelling prevent you from moving your fingers to their full potential.

Your surgical dressing or cast may be loosened by your doctor. To restore full motion, you might occasionally need to work with a physical or occupational therapist.

Severe (persistent) pain may indicate reflex sympathetic dystrophy, a condition that requires strong medication or nerve blocks for treatment. If you experience significant pain that does not go away when you take medicine, let your doctor know.

Rehabilitation and Return to Activity

Following a distal radius fracture, the majority of people resume all of their previous activities. The kind of damage, the type of care given, and the body’s reaction to that care all play a part. Following such injuries, you may occasionally have long-term functional difficulties.

The majority of patients will experience some wrist stiffness. After the cast is removed or following surgery, this usually gets better within a month or two and keeps getting better for at least two years. You will begin physical therapy a few days to weeks following surgery, or immediately upon removal of the last cast if your physician deems it necessary.

After the cast is taken off or surgery, most patients can return to light activities like swimming or working out their lower bodies in a gym in one to two months. It is possible to restart intense activities like football or skiing three to six months following the accident.

Kay and colleagues discovered that, for people recovering from casting and/or pinning for a distal radius fracture, a rehabilitation program comprising exercise and advice from a physiotherapist offered some extra advantages above no physiotherapy intervention. These advantages included decreased activity limits compared to controls at Week 3, better pain compared to controls at Weeks 3 and 6, and higher satisfaction compared to controls. In terms of grip strength or wrist AROM recovery, there was no difference between the two groups.

During immobilization:

Therapy referrals for DRF caseloads are made in less than 10% of cases at this point. Patient education and the management of edema and finger stiffness are priorities during immobilization. ROM of the shoulder, elbow, and fingers are addressed in most home exercise programs. Modalities that are hot or cold can be used to manage pain. Edema can be managed using retrograde massage and compressive bandages. Resting splints were employed to provide protection and support in half of the cases.

After immobilization:

At this point, ROM exercises and hot/cold modalities are used by 90% of therapists surveyed. Eighty percent combine soft tissue mobilization, joint mobilization, retrograde massage, and dexterity exercises with compressive wraps. To increase strength and function, nearly 90% of participants also performed strengthening activities. For the treatment of joint stiffness, splints can be either dynamic or static, or both.

Complications

When treating adult forearm fractures, both surgical and non-operative methods may result in complications:

- Broken bones frequently have sharp ends that can rip or cut nearby blood vessels or nerves.

- Following an injury, excessive bleeding and swelling may result in compartment syndrome, a condition where the edema stops the blood flow to the hand and forearm. It usually manifests 24 to 48 hours after the accident and is quite painful to move the fingers. Once diagnosed, compartment syndrome necessitates immediate surgery and can cause loss of function and feeling. In these situations, the muscle and skin coverings are released to release pressure and permit blood to flow again.

- Open fractures let the external environment contact the bone. The bone can get infected even after the muscle and bone have been carefully cleaned after surgery. Treatment for bone infections is challenging and frequently involves repeated operations and long-term antibiotics.

- Infection. Any surgery, whether it is performed to treat a forearm fracture or for another reason, carries a risk of infection.

- Damage to nerves and blood vessels. The area surrounding the forearm carries a small risk of nerve and blood vessel damage. It’s normal to have some temporary numbness in the aftermath of an injury, but if your fingers continue to tingle or numb, you should see your doctor.

- Synostosis. Another uncommon consequence is synostosis or the repair of a bone bridge that connects the forearm’s two bones. This may lessen bone rotation and impair the complete range of motion.

- Non-union. Surgery does not ensure that the fracture will heal. You might require additional surgery if the fracture does not heal.

- The screws, plates, rods, or cracks may break or pull away.

- Following reasons why this may occur, such as:

- After surgery, the patient does not adhere to instructions.

- The patient’s other medical conditions impede healing. Diabetes is one of the illnesses that slow healing. Healing is also slowed by tobacco use, including smoking.

- Healing is frequently slower if the fracture is caused by an open cut in the skin.

- Additionally, infections might impede or stop healing.

- Following reasons why this may occur, such as:

- Rigidity. The degree and location of your fracture will determine whether you experience wrist or elbow stiffness. You might no longer be able to fully raise and lower your palm.

- Uncomfortable or bothersome implants. Particularly if the plates are positioned on the ulna’s border, which is immediately beneath the skin, they could be uncomfortable. Later, symptomatic plates may be removed if the fracture has healed.

- Loss of reduction is the most frequent side effect during non-operative therapy. This indicates that the ends of the bones at the fracture site separate from one another. An operation might be necessary for this. Should you persist with non-operative treatment, you can feel stiff and have restricted wrist movement.

Prevention

By taking measures to avoid falls, keeping your bones healthy, and using the required safety procedures when driving, you can avoid suffering a distal radius fracture. To attain these, take the following actions:

- When engaging in high-risk hobbies like rollerblading, make sure you’re wearing the appropriate safety gear.

- When it’s cold outside, wear appropriate footwear, such as winter boots.

- Steer clear of slick areas, such as pathways covered in ice.

- Install handrails on your staircases and grab bars in your bathrooms.

- Maintain excellent bone density by eating a well-balanced, nutrient-dense diet that emphasizes calcium and vitamin D.

- Continue to be physically active all your life.

- When traveling in a car, buckle up.

Home Care

By taking the following actions, you might be able to assist your body’s natural healing process:

- Apply ice to your wrist for periods of 10 to 20 minutes.

- Observe the immobilization advice provided by your doctor.

- Until your doctor gives you the all-clear, do not take off your splint.

- Try to keep your wrist as high as possible to lessen swelling.

- To avoid becoming stiff, flex your fingers frequently.

Home Exercise

The following exercises could aid in your function recovery:

- exercises for range of motion, such as wrist circles

- stretches with the fingers

- forearm workouts such as wrist curls

- Exercises for strengthening the hands, such as gripping a hand exerciser

FAQs

Does a radial fracture recover by itself?

Most distal radius fracture patients recover on their own after wearing a cast or splint for a few weeks. Some people will need to have the fracture fixed surgically right away.

Can an unoperated radius fracture heal?

Certain fractures, such as those of the distal radius (before the wrist), can be repaired without surgery as long as the broken bone pieces are closely spaced and barely move. Our doctors will advise using a cast or splint to immobilize the hand in these situations.

Do radial fractures often occur?

One of the most typical kinds of bone fractures is a distal radius fracture. They are located at the end of the radius bone, near the wrist. Distal radius fractures can be categorized as Colles or Smith fractures based on the angle of the break. Fractures of the distal radius are mostly caused by falls.

Is a fracture to the radius serious?

It is critical to get medical help as soon as possible if you think you may have broken your distal radius bone. Wrist fractures can cause more problems if they are not addressed, which may have long-term consequences. Patients can choose from a variety of distal radius fracture alternatives.

How severe does a radial fracture hurt?

A distal radius fracture can cause symptoms such as, but not limited to, the following: acute, sharp wrist pain that occasionally coincides with the sound or feel of a snap during a fall or accident.

Reference

- Professional, C. C. M. (n.d.). Radius. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/24528-radius

- Distal Radius Fractures (Broken Wrist) – OrthoInfo – AAOS. (n.d.). https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/diseases–conditions/distal-radius-fractures-broken-wrist/

- Corsino, C. B. (2023, August 8). Distal Radius Fractures. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536916/

- Williams, R. S. (n.d.). Distal Radius Fracture: Signs, Symptoms, Causes, and Treatment Options. https://www.coastalorthoteam.com/blog/distal-radius-fracture-signs-symptoms-causes-and-treatment-options

- Yetman, D. (2022, September 22). What to Know About Distal Radius Fractures: Treatment, Recovery, and More. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/distal-radius-fracture#causes

- Distal radius fracture risk factors – wiki doc. (n.d.). https://www.wikidoc.org/index.php/Distal_radius_fracture_risk_factors

- Laino, D. (n.d.). Diagnosing a Distal Radius Fracture. Sports-health. https://www.sports-health.com/sports-injuries/hand-and-wrist-injuries/diagnosing-distal-radius-fracture

- Distal Radius Fracture (Wrist Fracture). (2021, August 8). Johns Hopkins Medicine. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/distal-radius-fracture-wrist-fracture#:~:text=Nonsurgical%20Treatment,wear%20for%20comfort%20and%20support.

- Distal Radial Fractures. (n.d.). Physiopedia. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Distal_Radial_Fractures

One Comment