Cartilage Transplant

What is a Cartilage Transplant?

Cartilage transplantation is a medical procedure that has gained prominence in recent years as a promising solution for addressing various joint-related issues and injuries. Cartilage, a specialized connective tissue that lines the surfaces of joints, plays a crucial role in joint mobility and cushioning. However, it is susceptible to damage due to injury, wear and tear, or degenerative conditions, leading to pain, reduced joint function, and decreased quality of life for affected individuals.

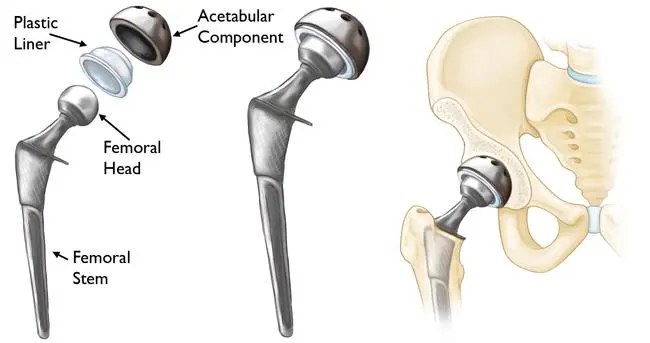

Traditional treatments for cartilage defects and injuries often fall short of providing long-lasting relief. These methods include rest, physical therapy, pain management, and in severe cases, joint replacement surgery. While effective to some extent, these approaches may not fully restore the natural function and biomechanics of the affected joint.

Cartilage transplantation represents a groundbreaking advancement in orthopedic medicine, offering a more targeted and potentially transformative solution for patients with cartilage injuries and defects. This innovative procedure aims to repair, regenerate, or replace damaged cartilage tissue, ultimately restoring joint function and relieving pain.

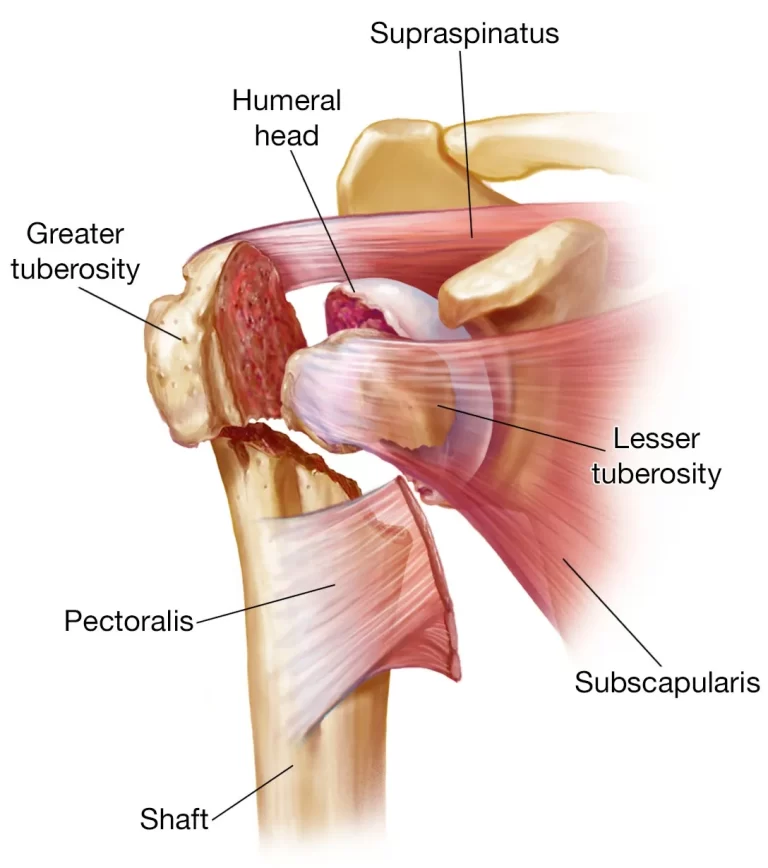

There are various approaches to cartilage transplantation, each tailored to the specific needs of the patient and the extent of cartilage damage. Autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI), osteochondral autograft transplantation (OAT), and allograft transplantation are some of the techniques employed by orthopedic surgeons to address cartilage issues. These methods can be used in joints such as the knee, hip, shoulder, and ankle.

Anatomy

Most people who have heard of torn cartilage tend to associate it with damage to the knee’s meniscus or shock absorber. Due to the lack of common information on the many forms of cartilage, this can be confused and misunderstood.

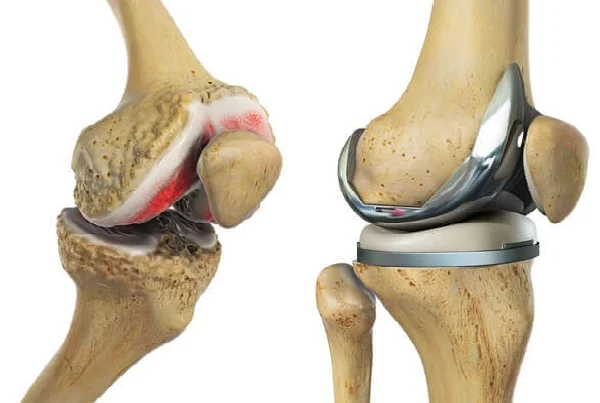

Articular cartilage is the “smooth Teflon lining” of the knee joint, which coats all the gliding surfaces and gives the knee joint its fluid, smooth appearance. It performs the mechanics of the knee joint very effectively when it is in its ideal state. Unfortunately, it is susceptible to damage, and when this smooth articular cartilage is destroyed, it may cause a lot more trouble than when the meniscus cartilage, the C-shaped shock absorber, is torn.

The most common condition impacting joints is osteoarthritis or damaged cartilage. Knee osteoarthritis is the most common type of the condition. Knee osteoarthritis restricts motion and produces chronic pain. Over many years, the knee cartilage deteriorates. Since cartilage lacks nerve endings (pain receptors), damage isn’t always noticeable until the cartilage’s supporting bone has already been damaged.

A new surgical method called a cartilage transplant, also known as a cartilage cell or chondrocyte transplant, involves repairing damaged cartilage with the patient’s own body’s own cartilage cells.

History

Articular cartilage abnormalities have until now received especially inferior care. The best that could be done to smooth it out was to use mechanical tools to shave it down. Unfortunately, there wasn’t much that could be done to fix a deficiency brought on by trauma or degeneration.

In an effort to encourage bleeding, the wounded area would occasionally be drilled with a wire. The idea was to build a fibrous clot that would eventually smooth out and form scar tissue, which would be preferable to a cartilage defect. Although this mending method was far from perfect, it was still an improvement over nothing. The plan was to pierce the bone plate directly below the cartilage and let blood leak into the area to promote cell migration.

This method is known as “microfracture” in modern terminology. When done properly, improvement in everyday activities can be anticipated in roughly 2/3 of patients.

The technique of abrasion chondroplasty is simpler to comprehend. If a hardened bone forms, a high-speed burr is utilized on the roughened area. Once more, the goal of this high-speed burr is to aid in the development of scar tissue; however, normal articular cartilage will take time to develop as a result.

The goals of a knee cartilage cell transplant:

reduce knee osteoarthritis discomfort

restoring the capacity to carry weight and participate in sports

Increased flexibility

Restore back the cartilage layer

Avoid having to replace a joint

Keep the joint healthy and stop knee osteoarthritis.

Knee osteoarthritis and knee cartilage transplant:

Knee osteoarthritis is not always treatable with a cartilage transplant. It is typically too late if the knee cartilage defect is too severe. In this situation, we would suggest either a full knee replacement or a partial knee replacement that preserves the joint.

There are several conditions for a successful cartilage transplant:

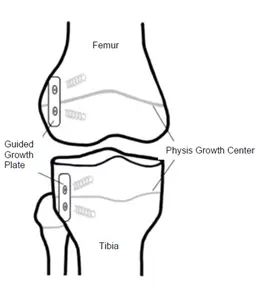

a sound knee with healthy collateral and cruciate ligaments

an undistorted joint axis (severe knock-knees or bow legs)

No loose bodies (tissue that separated as a result of the knee’s cartilage defect)

Menisci that have been preserved, for the most part

only one of the two joint surfaces of the cartilage is damaged.

Local cartilage abnormalities inside the knee are a common reason for transplanting cartilage cells, or chondrocytes.

The right conditions for a knee transplant of cartilage cells:

patient, 15 to 55 years old

10 square cm maximum defect size with surrounding healthy cartilage.

The ligaments should be intact, and the knee should be stable.

Ideally, there should be no abnormal load on the joint, such as from obesity.

Although individuals under the age of 55 are normally only advised to use this strategy, it is important to consider the patient’s biological age rather than their age on the calendar. When the conditions are right, cartilage transplants can even be done on patients who are over 65. To determine whether your particular case is appropriate for this operation, we need current X-rays and MRI images. Often, the knee specialist must do the surgery in order to decide between a partial prosthesis and a cartilage transplant.

There are other options (such as a partial prosthesis utilizing the Hemicap system, a Repicci prosthesis, or a complete replacement) to treat osteoarthritis of the knee if a cartilage cell transplant is not an option for you.

Surgical Procedure

Harvesting cartilage for a transplant involves the following steps:

Step 1: Obtaining a knee biopsy sample (sample of cartilage)

Using arthroscopy, the surgeon will first remove cartilage from the patient’s body. A healthy area of the knee that doesn’t support much weight is used to remove the cartilage tissue, which is around the size of a rice grain. Under a highly specialized cell culture lab, the cartilage cells are separated from this extracted tissue and grown under sterile conditions.

About 30 minutes are needed for this process. The patient has 120–150 ml of blood taken the following day from an arm vein. This blood is used in the lab to obtain the serum, which is the liquid component of the blood.

Step 2: Growing cells in the laboratory

The laboratory receives a blood sample from the patient and the harvested cartilage sample, which is the size of a rice grain. The cartilage cells are taken out of the tissue sample and cultivated sterilely in the patient’s blood serum. Any contact with proteins or blood components that are not natural to the body is fully ruled out by this method.

Small spherical cell aggregates containing millions of augmentable cartilage cells have developed at the end of the creation phase, which normally lasts 6 to 8 weeks. To maintain the quality of the cartilage cells, they are returned to the clinic in specially designed refrigerator-cooled containers within hours.

Surgical method

Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation (ACI)

ACI is an advanced procedure whose aim is to implant cells into the region where healthy hyaline cartilage is going to develop. Normal articular cartilage frequently contains a particular type of cartilage called hyaline cartilage. This method involves performing a biopsy during the initial arthroscopic surgery. A biopsy is the medical extraction of a sample of cells or tissues for analysis in order to diagnose the condition, cause, or severity of a disease.

During the biopsy, a little piece of cartilage is taken from a non-critical part of the knee joint. After that, it is transported to a lab where the tissue has been grown to create a large number of chondrocytes (cartilage cells) that can be transplanted back into the knee joint.

After that, the patient is brought back into the operating room for an open incision procedure. A syringe is used to inject liquid cartilage that has been generated in the lab underneath a patch. The patch is then completely covered, and the patient must wait until the knee is safe to bear weight before putting any weight on it.

Patients under the age of 55 and with lesions that are at least 2 square centimeters in size are often the only ones who can receive this procedure. However, it can be highly effective for lesions of the femoral condyles. It is not necessarily a good surgery for lesions on the patella (kneecap).

Any ligament instability in the knees must be treated initially, as must any deformities caused by improper alignments, such as congenital varus (bow-legged) abnormalities.

In cases of severe osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, this procedure is contraindicated. The patient may not be approved as a candidate for this treatment if they are clearly fat or have other medical contraindications.

Excellent long-term outcomes have been attained using autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI), both in terms of repairing cartilage and assisting patients in getting back to their pre-injury levels of activity. The statistics indicate improvements of up to 85% after a year. With time, the outcomes get better and better.

The fact that the patient’s own cartilage cells are implanted back into the knee joint accounts for the treatment’s high success rate and incredible recovery times. In order to regenerate hyaline cartilage in the knee without running the danger of material rejection or adverse effects, the cells are produced and cultured in the lab, multiplied, and then injected into the knee.

Osteochondral Autograft Transplantation (OAT)

OATS or mosaicplasty are other names for this technique. The typical lesion size for this surgery is 1-2 square centimeters. Once more, the aim of this procedure is to restore normal articular hyaline cartilage.

In this method, a section of hyaline cartilage is removed from a non-critical portion of the knee using specialized tools. Without any interim laboratory growth phase, this cartilage is directly transplanted into the region of the injured cartilage. This means that the amount of cartilage that can be taken out of the knee’s non-critical portion will determine the magnitude of the transplant. This is the reason lesions larger than 2 square centimeters cannot be treated with it.

The benefit is that it can be done arthroscopically in a single session. By drilling over the region known as the donor site with hollow tubes, the grafts are harvested. After drilling out the injured location, the bone and cartilage transplant tube is inserted there. This procedure eliminates the need for two operations and provides the benefit of a significantly reduced recovery time.

What happens during surgery?

Most of the laboratory-grown cartilage cells are implanted arthroscopically or with the least amount of intrusion possible. The required devices can be inserted into the knee with just a few small skin incisions.

The knee’s diseased cartilage tissue will first be removed by the surgeon, and the prepared deficient area will then be filled with cultured cartilage spheres (chondrospheres). After a few weeks, the defect will be filled in by connective tissue typical of cartilage that forms as it quickly adheres to the bone.

After about 10 minutes, the connective molecules (adhesion proteins) of the cartilage cells develop a mechanically stable adhesion to the bone once they make contact with the formed cartilage defect. The deficiency is gradually filled up by the cartilage cells as they expand. Depending on whether additional adjustments are needed, such as to the cruciate ligaments or the meniscus, the surgery is completed and lasts for around 30 to 60 minutes.

A successful cartilage transplant depends on identifying and treating the issues that led to the cartilage damage (such as misalignments, cruciate ligament tears, meniscus damage, etc.), which usually takes place at the same time as the cartilage transplant. The patient only needs to go through one round of slightly time-consuming aftercare and rest in the same way.

Post-operative prevention:

The post-operative courses vary depending on the type of surgery.

With the microfracture method, the patient might need to avoid bearing any weight for six weeks, but otherwise, they might heal fairly rapidly.

With an OATS treatment, when the cartilage is transplanted all at once, the patient will again be immobile for roughly 6 weeks before making a rapid recovery.

However, it must be understood that this approach is utilized for more difficult medical problems and larger wounds. The recovery period for the Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation technique, where the cartilage is manufactured in a lab, is substantially longer. Additionally, compared to the other two operations, the ACI approach requires a very big open incision.

Recommendations for following the first arthroscopy

2 days for inpatient care

The ideal time to stay on the property is seven days.

Two weeks off work is advised.

Five days are suggested for stitch removal.

Two weeks before being able to drive once more

Following cell implant, which, if necessary, addresses the root cause of the cartilage damage (2nd treatment), recommendations

3 days for inpatient care

6 weeks for the surgical leg to recover fully.

Following that, the operated limb can bear some weight for 6 to 8 weeks.

The recommended period of time to stay on the property is 10 days.

Six weeks off work is advised.

Seven to twelve days are advised for stitch removal.

Time till you can drive again: 6 to 12 weeks

Summary

One of the most difficult medical conditions to address in the knee is arthritic deterioration of the joint’s surface. For people with these issues, there wasn’t much that could be done up until recently.

It is important to recognize and comprehend the dangers and restrictions of each of the abovementioned processes. The operations do give patients a chance to have a healthy knee joint once more, allowing them to return to regular activities and restore their fitness, even though the final treatment results cannot be promised with confidence or guaranteed.

FAQs

What occurs before the procedure?

To get a clear overall picture, the doctor will first do extensive medical diagnostics. This includes a review of your medical history, a physical exam, X-rays taken while you are bearing weight, and MRI scans to determine how much cartilage damage has occurred. The attending doctor will describe the procedure and any potential problems of surgery after establishing that the patient is healthy enough for surgery. The patient will also meet with the anesthetist, who will once more thoroughly assess the patient’s condition to determine whether it is suitable for anesthesia. The procedure can usually be carried out the next day if it has been cleared by the surgeon and anesthesiologist

What kind of anesthetic is applied during a transplant of cartilage cells?

Under general anesthesia, the cartilage cell transplant is normally carried out. To lessen the dangers of general anesthesia, we can potentially conduct it under spinal anesthesia. In this instance, the anesthetist administers the anesthetic by injecting it into the lumbar spine’s spinal canal. In this case, the patient is awake during the operation. Our anesthetists are very skilled in both techniques and will decide during a pre-operation conversation which one is appropriate for you and your needs.

Should I expect discomfort following my surgery?

Pain is a natural part of any surgery, but we always work to reduce it. Before the procedure, the anesthetist will frequently perform a procedure known as a “nerve block” that will temporarily paralyze the affected knee for 30 hours. The bulk of the pain is effectively managed by this action alone, and any persistent discomfort is then simply treated with standard medicine. It wants you to feel as little discomfort as possible.

What should I remember following surgery?

Following the surgery, you should elevate and ice your knee. After the surgery, the stitches will be removed between 7 and 12 days later. You can resume taking showers once these have been taken off. To avoid difficulties, you should give your knee some rest and refrain from carrying any weight for about six weeks. Depending on where the cartilage defect was located, you may be given a customized M4-orthosis to prevent the knee from bending excessively. Additionally, we will give you crutches and medical sick time during this time. Thrombosis preventative medications are essential when you can’t put all of your weight on the affected leg. To avoid muscle atrophy and keep the knee functioning, extensive rehabilitation is crucial at this point.

Is a cartilage cell transplant right for someone?

To carefully assess the cartilage damage in your knee, we need fresh MRI images and X-rays. These scans will be utilized to determine whether you are suitable for the surgery. If your particular situation is not suitable for a cartilage transplant, we can gladly provide you with information on alternative treatment alternatives.

References

- Abstracts. (2006). Pediatric Nephrology, 21(10), 1493–1635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-006-0236-x

- Archer, C., & Ralphs, J. (2010). Regenerative medicine and biomaterials for the repair of connective tissues. Elsevier.

- Caffarelli, C., Montagnani, A., Nuti, R., & Gonnelli, S. (2017). Bisphosphonates, atherosclerosis and vascular calcification: update and systematic review of clinical studies. Clinical Interventions in Aging, Volume 12, 1819–1828. https://doi.org/10.2147/cia.s138002

- Dermatopathology. (2012). Modern Pathology, 25, 113–137. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2012.14

- Mirzayan, R. (2011). Cartilage injury in the athlete. Thieme.