Cervicocranial Syndrome

What is Cervicocranial Syndrome?

Craniocervical syndrome, also known as Barre-Lieou syndrome, craniocervical junction syndrome, or posterior cervical sympathetic syndrome, is a condition characterized by various symptoms such as vertigo, headaches, tinnitus, facial pain, ear pain, difficulty swallowing, and pain in the carotid artery.

These symptoms are believed to be caused by factors related to the neck and cervical spine. However, the classification of the craniocervical syndrome as a distinct neurological entity is still a matter of debate, and it is often used as a term to describe a collection of undiagnosed symptoms, particularly those following acute neck injuries.

Originally described as a chronic condition, it has been associated with occipital headaches, nystagmus (involuntary eye movement) upon head movement, spasms, blurred vision, increased sensitivity of the cornea, and corneal ulcers. Other reported symptoms include anxiety, depression, and memory and cognitive disorders. Trauma or arthritis affecting the third and fourth cervical vertebrae or discs are often implicated as potential causes, leading to disturbances in the cervical sympathetic nerves and compromised blood circulation within cranial nuclei V and VIII.

According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), craniocervical syndrome is a neurological condition that arises from an injury to the sympathetic nerves in the cervical spine. This injury is typically attributed to arthritis or compression by nearby vertebrae. Symptoms commonly associated with this syndrome include facial pain, chronic allergies, dizziness, neck pain, ear pain, and vertigo.

It is worth noting that much of the existing literature on this topic predates 1990 and is often found in journals related to chiropractic care, acupuncture, and manipulative therapies. While the validity of craniocervical syndrome is not universally accepted within the medical community, the term continues to be used in certain publications. In 1928, Yang Choen Lie described a sympathetic disorder associated with cervical “arthritis” in his thesis, which contributed to the early understanding of this condition.

Anatomy related to Cervicocranial Syndrome

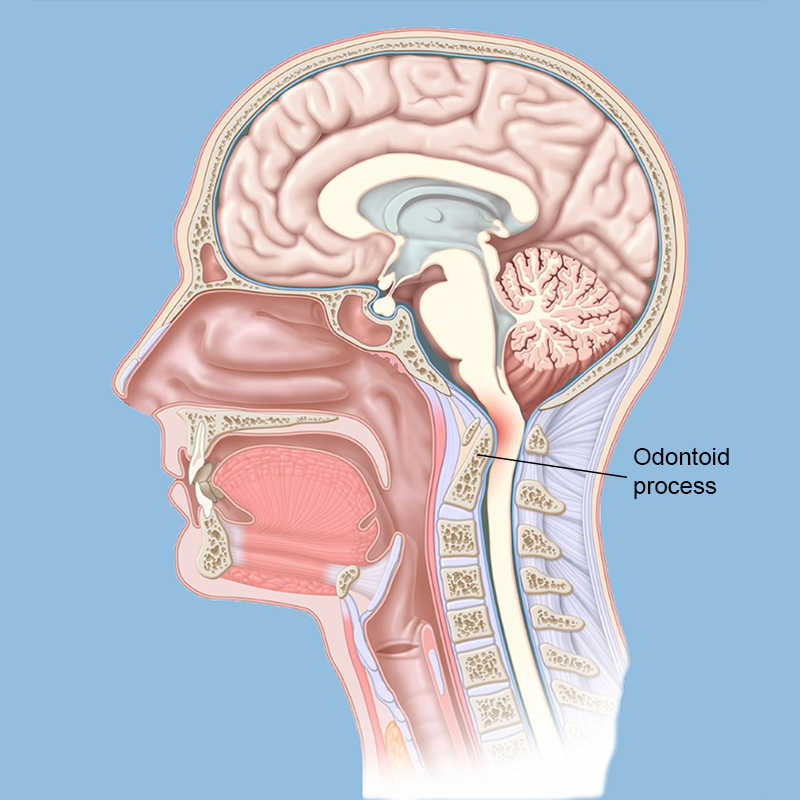

The craniocervical junction refers to the region between the skull and the cervical spine. It encompasses the base of the skull, the first two cervical vertebrae, and the neural structures that pass from the brain into the cervical spine.

At the base of the skull, there is a large opening known as the Foramen Magnum. This opening allows important structures to pass through. These structures include:

- The Spinal Cord: It is a cylindrical bundle of nerve fibers that extends from the base of the brain down to the lower back. The spinal cord carries signals between the brain and the rest of the body, controlling both voluntary and involuntary bodily functions. It is protected by spinal bones that surround it and also by cerebral spinal fluid, which acts as an additional layer of protection.

- Nerves: As the spinal cord descends through the foramen magnum and the spine, numerous nerves branch off and travel to different parts of the body. This includes the 12 cranial nerves, which control muscles and are connected to internal organs like the heart and lungs.

- Arteries and Veins: These blood vessels supply blood flow to and from vital structures in the head, neck, and body, ensuring proper functioning.

- Ligaments: Ligaments play a crucial role in maintaining alignment and stability. They act as the “duct tape” that holds everything together in the craniocervical region.

The spinal cord exits the skull through the foramen magnum and descends through the neck, surrounded and protected by the spinal bones and cerebral spinal fluid. It is important to note that the spinal cord is delicate and sensitive to trauma, compression, and excessive movement. Any impairment or compromise in the transmission of important information from the brain through the spinal cord can lead to a wide range of symptoms and conditions, which will be discussed in a future post.

Causes of Cervicocranial Syndrome

The causes of the craniocervical syndrome can be congenital and acquired.

Congenital Causes

Congenital abnormalities of the craniocervical junction can manifest as either specific structural anomalies or as part of general or systemic disorders that affect skeletal growth and development. Many patients with these abnormalities exhibit multiple variations.

Some examples of structural skeletal abnormalities include:

- Os odontoideum: This is characterized by the presence of an anomalous bone that replaces all or part of the odontoid process.

- Atlas assimilation: It refers to the congenital fusion of the atlas (the first cervical vertebra) with the occipital bone (base of the skull).

- Congenital Klippel-Feil malformation: This condition, often associated with Turner syndrome or Noonan syndrome, is characterized by the fusion of multiple cervical vertebrae. It is frequently accompanied by atlantooccipital anomalies.

- Atlas hypoplasia: In this condition, the atlas bone is underdeveloped.

- Platybasia: This refers to the flattening of the base of the skull, often accompanied by basilar invagination (the upward protrusion of the base of the skull into the cranial cavity). Chiari malformations, which involve the descent of the cerebellar tonsils or vermis into the cervical spinal canal, can also be associated with platybasia, along with other abnormalities.

In addition to specific structural anomalies, there are systemic disorders that affect skeletal growth and development and can impact the craniocervical junction. Some examples include:

- Achondroplasia: This condition is characterized by impaired bone growth at the growth plates (epiphyses), resulting in shortened and malformed bones. In some cases, it can lead to the narrowing or fusion of the foramen magnum (the opening at the base of the skull) with the atlas, potentially causing compression of the spinal cord or brainstem.

- Down syndrome, Morquio syndrome (mucopolysaccharidosis IV), and osteogenesis imperfecta: These conditions can cause atlantoaxial subluxation or dislocation, which refers to abnormal movement or misalignment between the atlas and the axis (the second cervical vertebra).

Acquired Causes

Acquired causes of craniocervical junction issues can arise from various injuries and disorders.

The most common disease-related cause is rheumatoid arthritis.

Injuries to the craniocervical junction can involve the bones, ligaments, or both, often resulting from accidents such as vehicle or bicycle crashes, falls, and particularly diving accidents. Some severe injuries can lead to immediate fatality.

Paget’s disease of the cervical spine is an illness that can contribute to atlantoaxial dislocation and subluxation, basilar invagination, and platybasia.

Metastatic tumors that affect the bones can also lead to atlantoaxial dislocation or subluxation.

Slow-growing tumors at the craniocervical junction, such as meningiomas and chordomas, have the potential to exert pressure on the brainstem or spinal cord.

Symptoms of Cervicocranial Syndrome

Symptoms and signs of craniocervical junction abnormalities can manifest spontaneously or following a minor neck injury, and their progression can vary. The presentation of these abnormalities depends on the degree of compression and the structures affected.

The most commonly observed manifestations include:

- Neck pain, often accompanied by headaches.

- Symptoms and signs of spinal cord compression.

- Neck pain may radiate to the arms and be associated with headaches, especially occipital headaches radiating to the top of the skull. This pain is constantly attributed to compression of the C2 nerve origin, the more prominent occipital nerve, and local musculoskeletal dysfunction. Neck pain and headaches typically worsen with head movement and can be triggered by coughing or bending forward. In patients with Chiari malformation and coexisting hydrocephalus, headaches may worsen when in an upright position due to increased hydrocephalus.

- Spinal cord compression primarily affects the upper cervical cord.

- Impaired motor function, resulting in spastic weakness in the arms, legs, or both, due to compression of motor tracts.

- Typically, inadequate joint position & vibration intentions (posterior column function).

- Tingling sensation down the back, often extending into the legs, with neck flexion (known as Lhermitte’s sign).

- Less commonly, impaired pain and temperature sensations (spinothalamic tract function) in a stocking-glove pattern.

- Abnormalities in neck appearance and range of motion.

- Certain abnormalities, such as platybasia, basilar invagination, or Klippel-Feil malformation, can affect the neck’s appearance or restrict its range of motion. The neck may appear short, have a webbed appearance (with a skinfold extending from the sternocleidomastoid muscle to the shoulder), or be positioned abnormally (e.g., torticollis in Klippel-Feil malformation). A limited range of motion may also be observed.

- Brain compression (caused by conditions like platybasia, basilar invagination, or craniocervical tumors) can result in deficits involving the brainstem, cranial nerves, and cerebellum.

- Brainstem and cranial nerve deficits may include sleep apnea, internuclear ophthalmoplegia (weakness in eye adduction on the affected side and horizontal nystagmus in the abducting eye during lateral gaze), downbeat nystagmus (fast element downward), hoarseness, dysarthria, & dysphagia.

- Cerebellar deficits typically manifest as impaired coordination.

- Vertebrobasilar ischemia which can be begun by modifications in head position may conduct to symptoms for example intermittent syncope, drop attacks, vertigo, confusion or altered consciousness, weakness, & visual disturbances.

- Syringomyelia, a cavity within the central part of the spinal cord, is commonly found in patients with Chiari malformation and may cause:

- Segmental flaccid weakness and atrophy, predominantly affecting the distal upper extremities.

- Loss of pain and temperature sensations in a capelike distribution over the neck and proximal upper extremities.

Diagnosis of Cervicocranial Syndrome

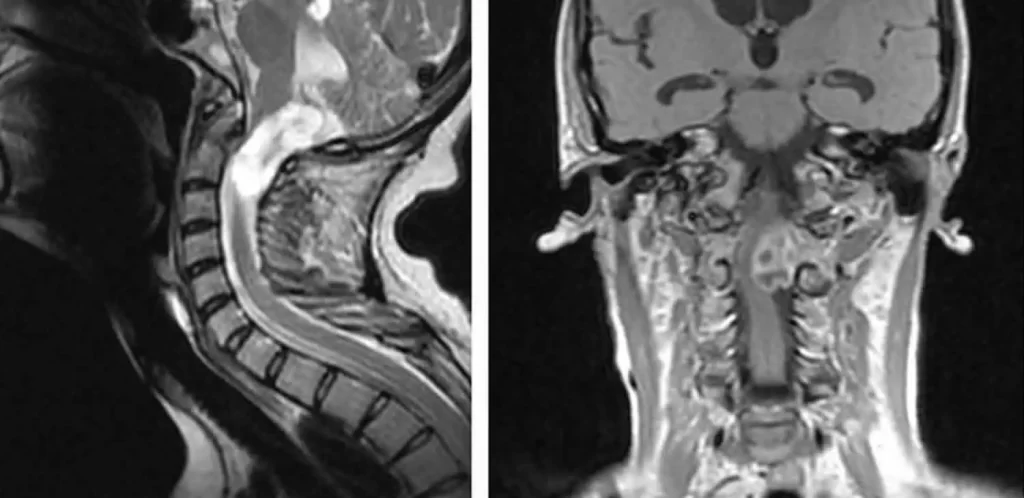

Craniocervical abnormalities are suspected in patients who experience neck or occipital pain along with neurologic deficits that can be attributed to the lower brainstem, upper cervical spinal cord, or cerebellum. Clinical evaluation, including assessment of the level of spinal cord dysfunction, can often help differentiate between lower cervical spine disorders and craniocervical abnormalities. Additionally, neuroimaging plays a crucial role in the diagnosis process.

Neuroimaging techniques, such as MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) or CT (computed tomography), are commonly employed to evaluate the upper spinal cord, brain (especially the posterior fossa), and the craniocervical junction when a craniocervical abnormality is suspected. In cases of acute or rapidly progressive deficits, immediate imaging is warranted as an emergency. Sagittal MRI is particularly effective in identifying associated neural lesions, including abnormalities in the medulla, pons, cerebellum, spinal cord, and blood vessels, as well as conditions like syringomyelia. CT scans provide accurate visualization of bone structures and can be performed more readily in emergency situations.

If MRI or CT is not available, or if the results are inconclusive, plain x-rays may be taken. These x-rays typically include lateral views of the skull and cervical spine, as well as anteroposterior and oblique views of the cervical spine.

In cases where MRI is unavailable or inconclusive and CT results are inconclusive, CT myelography (a CT scan performed after injecting a contrast agent into the spinal canal) may be performed. If MRI or CT scans suggest the presence of vascular abnormalities, further imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance angiography or vertebral angiography may be recommended.

Treatment for Cervicocranial Syndrome

Medical Management

Medication:

As cervicocranial syndrome primarily affects the biomechanical aspects of the condition, the role of medication is primarily symptomatic. There is no evidence to suggest that medication has an impact on the volume or consistency of cervical discs. However, medication has been shown to effectively relieve deep and severe pain associated with the syndrome.

Sedatives and tranquilizers may also be prescribed to reduce central sensitization to biomechanical stress and alleviate night pain, which can lead to physical and emotional stress. It is important to note that medication should be used as an adjunct to physical therapy and that patient education is crucial to prevent misuse and associated risks.

Local Muscle Infiltration:

When medication and heat therapy do not provide sufficient pain relief or muscle relaxation, local muscle infiltration may be recommended. This procedure involves injecting local anesthetics or steroids directly into the affected muscles to alleviate pain and muscle spasms.

Cervical Epidural Injection:

If other medication and heat therapies fail to provide adequate pain relief, cervical epidural injections may be considered. This involves injecting a combination of local anesthetics and corticosteroids into the epidural space around the spinal cord to reduce inflammation and alleviate pain.

Cervical Sympathetic and Radicular Blockade:

In some cases, cervical sympathetic and radicular blockade techniques may be employed to manage pain associated with cervicocranial syndrome. These procedures involve injecting medications or performing nerve blocks to target specific pain pathways and provide pain relief.

Surgery:

In exceptional cases when conservative therapies are ineffective, surgery may be considered for patients with chronic and recurrent cervicocranial syndrome experiencing severe and unbearable pain. Percutaneous drill resection is a technique that involves using a radiofrequency generator to heat and destroy tissue, with reported success rates of 85-95%. Another minimally invasive option is CT-guided radiofrequency thermocoagulation, which is an effective and precise treatment for non-radicular cervical pain caused by zygapophysial joint arthropathy when other interventions have not provided lasting improvement.

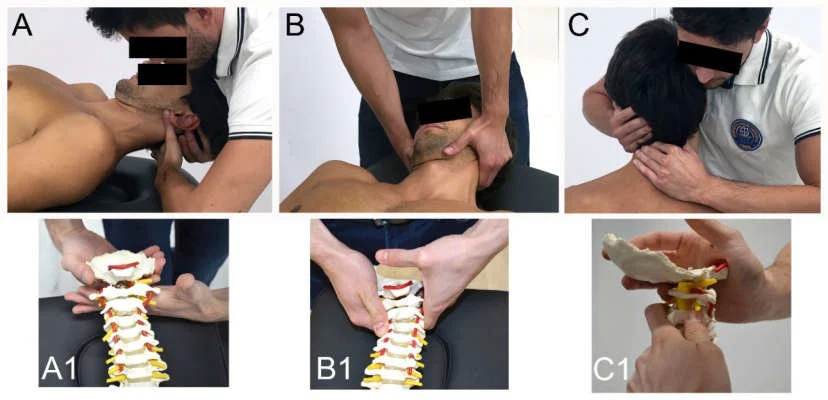

Physical Therapy Management

Manipulation: Moderate evidence suggests that manipulation combined with mobilization of the cervical spine can be effective. However, when compared to an active control treatment, there is low evidence for pain relief and functional improvement. Thoracic manipulation may be considered an additional therapy for pain relief.

Mobilization: Limited evidence suggests that mobilization alone may not result in significant improvement. There is no significant difference compared to acupuncture for acute pain reduction.

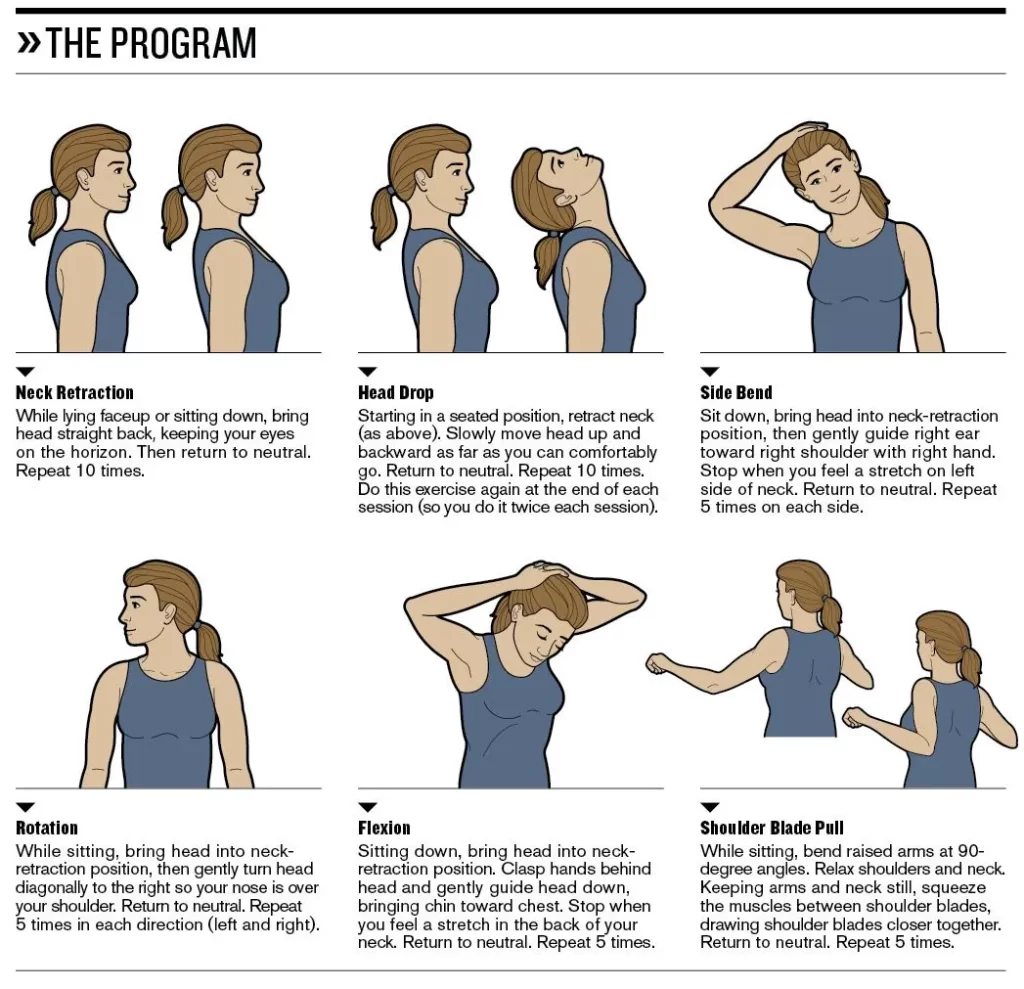

Exercise: Stretching and strengthening exercises targeting the cervical region and surrounding areas show moderate-quality evidence for pain reduction and functional improvement in the short to intermediate term. Low-quality evidence suggests that general fitness training exercises may not provide a significant difference in pain compared to a reference intervention that focuses on health counseling, workplace ergonomics, diet, relaxation, and stress management.

Electrotherapy: Very low to low evidence suggests that techniques such as transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), electrical muscle stimulation (EMS), pulsed electromagnetic field therapy, and repetitive magnetic stimulation may have a greater therapeutic effect compared to placebo treatments.

Patient education: Providing education about the positive effects of physical exercise is important to improve adherence and patient satisfaction.

Traction: Based on a review of seven randomized controlled trials (RCTs), there is no significant difference in pain reduction and daily functioning between traction therapy and a placebo treatment.

Endurance training: Moderate-quality evidence suggests that scapulothoracic/upper extremity endurance training can provide moderate pain relief immediately post-intervention for (sub)acute/chronic mechanical neck disorders.

Stretching: Low-quality evidence indicates that stretching exercises, whether performed before or after manipulation, do not significantly affect pain and function compared to manipulation alone in cases of chronic neck pain immediately post-treatment.

Neuromuscular exercises: Uncertainty remains regarding the effectiveness of eye-neck coordination exercises in improving pain and function. Very low-quality evidence suggests that eye-neck coordination exercises may provide moderate pain reduction and improved function in the short term for chronic neck pain. However, further research is needed to establish the benefits of these exercises.

Examples of neuromuscular exercises may include:

- Head repositioning with eyes closed.

- Head repositioning with resistance was provided by the physiotherapist.

- Shoulder repositioning while maintaining a neutral head position.

- Shoulder repositioning with eyes closed.

Prognosis of Cervicocranial Syndrome

The prognosis for individuals with cervicocranial syndrome can vary depending on various factors, including the presence of coexisting medical conditions and the nature of the trauma involved. When there is instability in the cervical spine, it can pose a risk to the patient’s neurological well-being. However, corrective and decompressive cervical spinal surgeries have been shown to significantly improve quality of life and alleviate symptoms.

Following surgery, a high percentage of patients, ranging from 93 to 100 percent, report a reduction in cervicocranial syndrome symptoms, such as neck pain. It is important to note that the specific prognosis for each individual should be determined by a healthcare professional based on a comprehensive evaluation of their condition and the factors influencing their case.

Conclusion

Cervicocranial syndrome is associated with deep or superficial pain in the head, dizziness, and often auditory or visual disturbances (e.g. nystagmus & tinnitus) induced by spondylotic irritation & actual compression resulting in pain and restriction of motion of the upper cervical spine. In terms of physiotherapy, there is low evidence for pain relief with manipulation, mobilization, exercise therapy (stretching, strengthening, general fitness), electrotherapy, education, and neuromuscular exercises.

FAQs

Is cervicalgia serious?

Anyone can be impacted by cervicalgia, which directs to an ache in the neck that doesn’t spread to other regions, for example down the arms. Cervicalgia isn’t usually a severe situation, but it can generate discomfort and should be managed instantly.

Can cervical spine problems be cured?

Even though there are several very useful nonsurgical & surgical cure alternatives available to alleviate the symptoms of cervical myelopathy & radiculopathy, there is no cure for the degenerative modifications in the cervical spine that induced the symptoms.

How is cervicocranial syndrome diagnosed?

A definitive test for diagnosing cervicocranial syndrome is the help of thermography to notice inflammation for disclosing medical problems. This test uses the help of an infrared camera to notice warmth patterns & blood flow.

How do you treat Cervicocranial syndrome?

Treatment options contain acquiring chiropractic care, physiotherapy, nerve block injections, and also surgery. Prolotherapy & Platelet Rich Plasma (PRP) as well as control cell techniques, which are suggested in the office at GRM, have been indicated to assist regale Cervicocranial Syndrome.

What is the cause of Cervicocranial syndrome?

The reason for cervicocranial syndrome is either a weakness (genetic modification/development of conditions later in life) or damage pertaining to the neck: the cervical region, that impairs the spinal nerves traveling via the cervical area resulting in ventral subluxation.

One Comment