Femur Bone

Introduction

The longest and hardest bone in the human body is your femur. It significantly affects your gait, posture, and ability to stay balanced.

Usually, only severe traumas like auto accidents cause femurs to break. You might not even be aware of the increased risk of fractures caused by osteoporosis, which weakens bones.

There is only one bone in the thigh, the femur, or thigh bone. The part of the lower limb between the hip and the knee is called the thigh.

The femur represents the upper leg bone in many four-legged animals.

The bottom of the femur joins the tibia and patella to form the kneecap, while the top of the femur rests in the hip joint, a socket in the pelvis. The largest and thickest bone in the human body is the femur.

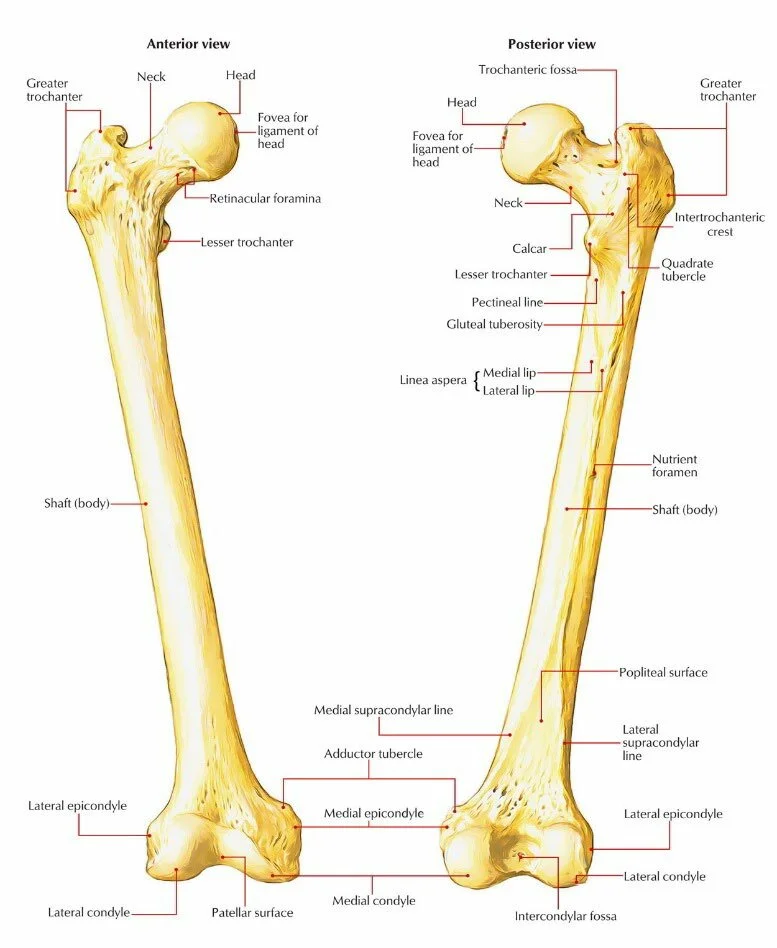

The longest, heaviest, and strongest bone in the human body is the femur bone. The cylindrical shaft at the base and the spherical head at the apex are attached to the pyramid-shaped neck at the proximal end.

The greater and lesser trochanters, two noticeable bone protrusions, connect to the muscles that move the hip and knee. In a normal adult, the inclination angle—also called the angle between the neck and shaft—measures approximately 128 degrees.

However, the inclination angle decreases with aging. Other key components include the linea aspera and the adductor tubercle, which serve as the attachment points for the posterior half of the adductor magnus.

The femoral head is enclosed by the acetabulum of the pelvis, creating the hip, which is a ball-in-socket joint.

The head is oriented somewhat anteriorly, superiorly, and medially. The fovea capitis femoris, a pit on the head, is connected to the acetabulum via the ligamentum teres femoris.

The anterior arch of the shaft is moderate. The shaft of the medial and lateral condyles spreads out in a cone shape at the distal femur, landing on a cuboidal base.

The femur and tibia unite at the medial & lateral condyles to form the knee joint.

To reduce friction and increase the range of motion, cartilage covers the synovial joints of the hip and knee. The two bony ridges that connect the two trochanters are the trochanteric crest posteriorly and the intertrochanteric line anteriorly.

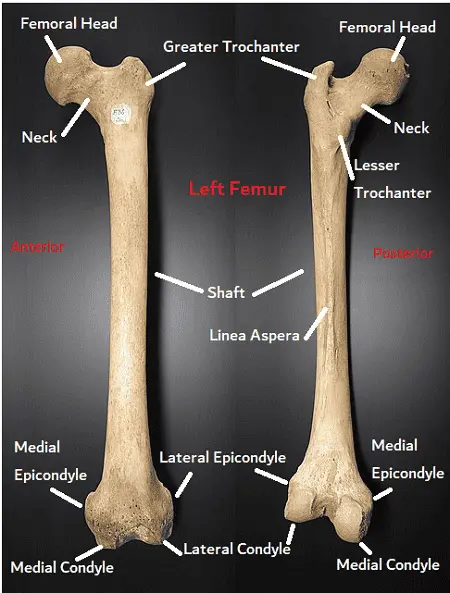

Anatomy of the bone

The longest, heaviest, & strongest bone in the body of a person is the femur. The two main functions of the femur are stability of walking and weight bearing. A crucial connection in the kinetic chain is below.

The strong hip and knee muscles that support walking as well as other propulsive motions have several strong attachment points thanks to the femur’s robust structure.

Femur, the upper or posterior leg bone. The head and hip joint, known as the acetabulum, resembles a ball and socket, with the head being held in place by the ligamentum teres femoris inside the socket and the strong ligaments around it.

In humans, the femur’s neck forms an effective 125° angle with the head to shaft during gait. The gluteus medius and minimus muscles attach to the femur’s prominence at the outside of the thigh.

The linea aspera, a bony pillar, strengthens the shaft from behind and gives it a slight forward convexity.

The patella, or kneecap, and tibia, or shin, complete the bottom half of the knee joint. The upper half of the knee joint is formed by two sizable prominences, called condyles, on either side of the lower end of the femur.

The femur exhibits the growth of internal arcs of bone termed trabeculae, which are well-organized to transfer pressure and withstand tension.

It has been demonstrated that human femurs can withstand compression forces ranging from 800 to 1,100 kg (1,800 to 2,500 pounds).

Human leg skeleton and muscle structure (left) and gorilla leg skeleton and muscle structure (right).

In humans, the femur is long and rather fragile or slender, while in great apes, it is shorter, more curved, and more robust.

The longest bone in the body and the only bone in the thigh is the femur.

It is composed of three parts: proximal, shaft, and distal. It serves as the origin and attachment point for numerous muscles and ligaments.

Where is the femur located?

The only bone that’s found in your thigh is the femur.It reaches the knee from the hip.

How does the femur appear?

The femur is composed of a long shaft in the middle and two rounded ends. It’s the traditional form seen on bones in cartoons: a cylinder with two concentric circles on either end.

Anatomy

The solitary bone in the upper leg is the femur. The proximal ends of the tibiae are articulated with the two femurs as they converge medially toward the knees.

One of the main factors influencing the femoral-tibial angle is the femora’s angle of convergence. Femora in humans converge more in females than in males due to the bigger pelvic bones in females.

When someone has knock knee or genu valgum, their femurs converge to the point where their knees touch. The other extreme is known as genu varum, or “bow-leggedness.”

In the general population, the femoral-tibial angle is approximately 175 degrees in those without either genu varum or genu valgum.

The largest & thickest bone in the body of an individual is the femur. It is also the strongest bone in the human body according to certain tests. This is dependent upon the kind of measurement used to determine strength, such as machine testers for tensile strength.

The temporal bone in the skull is the strongest bone, according to certain strength tests. In anthropology, the average femur length is useful because it provides a basis for a realistic approximation of a subject’s height from an incomplete skeleton.

This ratio is found in both men and women, as well as most ethnic groups, with relatively limited variance. It is 26.74% of a person’s height on average.

The femur is classified as a long bone and consists of two diaphyses (extremities) that articulate with neighboring hip and knee bones and a diaphysis (shaft or body).

Proximal part of the bone

Consists of the greater and lesser trochanters, the neck, and the head. The hip joint is formed by the articulation of the femur head and the pelvic acetabulum.

The hip joint is formed by the proximal end of the femur articulating with the pelvic acetabulum.

It consists of a head and neck, two bony processes, and the greater and lesser trochanters. The two bony ridges that connect the two trochanters are the trochanteric crest posteriorly and the intertrochanteric line anteriorly.

The head of the femur

Two-thirds of a sphere makes up the head of the femur, which articulates with the pelvic bone’s acetabulum.

It has a little groove, called a fovea, that connects to the sidewalls of the acetabular notch via the round ligament. The neck, or collum, is where the femur’s head and shaft are joined.

Articulates to create the hip joint with the pelvic acetabulum. Its smooth surface is coated in articular cartilage, with the exception of the fovea, a tiny indentation where the ligamentum teres is attached.

The neck of the femur

The neck is 4-5 cm long, with a compressed central section and the smallest diameter from front to back. The collum and shaft make an angle that is roughly 130 degrees.

This is a very variable angle. It is approximately 150 degrees in a baby and 120 degrees on average in an elderly person.

Coxa vara refers to an abnormal decrease in angle, and Coxa valga refers to an unnatural increase in angle. It is impossible to palpate the head or neck of the femur because they are so deeply entrenched in the hip muscles.

It is possible to feel the head of the femur deep as a profound (deep) resistance for the femoral artery in thin individuals with laterally rotated thighs.

The hip joint capsule and muscle attachments make the area where the head and neck meet extremely rough.

Joins the shaft of the femur to its head. It extends superiorly and medially and has a cylinder-like form. It is positioned with respect to the shaft at a about 135-degree angle. At this angle of projection, the hip joint has a greater range of motion.

The greater trochanter

The most lateral conspicuous part of the femur is the greater trochanter, which resembles a box. The greater trochanter’s peak is situated above the collum and extends to the hip joint’s midway. One can feel the greater trochanter with ease.

The furthest lateral bone protrusion that may be felt, is directly behind the neck, and originating from the anterior side.

Numerous muscles in the gluteal area, including the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and piriformis, attach to it. This is where the vastus lateralis originated.

An avulsion fracture of the greater trochanter may occur from a severe contraction of the gluteus medius.

On the medial surface of the greater trochanter, the trochanteric fossa is a deep depression that is bordered posteriorly by the intertrochanteric crest.

The lesser trochanter

The lowest portion of the femur neck extends into the lesser trochanter, which is formed like a cone. The intertrochanteric line on the front and the intertrochanteric crest on the back connect the two trochanters.

Less in size than the larger trochanter. It emerges from below the neck-shaft junction on the posteromedial side of the femur.

It is where the iliopsoas attaches, and a hard contraction of it can result in a lesser trochanter avulsion fracture.

The intertrochanteric crest

Known as the linea quadrata (or quadrate line), this minor ridge can occasionally be seen starting at the middle of the intertrochanteric crest and extending vertically downward for approximately 5 cm along the back of the body.

The quadrate tubercle is situated about where the upper third and lower two-thirds of the intertrochanteric crest converge. This is a bone ridge that joins the two trochanters, much as the intertrochanteric line.

It is situated on the femur’s posterior surface. The quadrate tubercle, which is spherical and on its superior half, is where the quadratus femoris attaches.

The intertrochanteric line

a bone ridge that connects the two trochanters on the anterior surface of the femur and travels anteromedially. Once it passes through the lesser trochanter on the posterior surface, it is known as the pectineal line.

The iliofemoral ligament, which is the strongest ligament in the hip joint, is attached to it.

The shaft of the Femur bone

The femoral shaft has a nearly cylindrical shape, with a pronounced longitudinal bone ridge known as the linea aspera. It is significantly wider superiorly and slightly arched, giving it convexity anteriorly and concavity posteriorly.

Many muscles, with the exception of the gluteus maximus and vastus intermedius, originate from and insert into the femoral shaft. These muscles engage with the posterior surface of the bone.

The femur’s (or shaft’s) body is broad, thick, and nearly cylindrical in shape. It is broadest and somewhat flattened from above backward bottom, and a little broader above than in the center.

It has a slight arched shape that makes it concave behind and convex in front. A noticeable longitudinal ridge called the linea aspera, which diverges proximally and distally as the medial and lateral ridge, strengthens this structure.

The medial ridge of the linea aspera continues as the pectineal line, whereas the lateral ridge becomes the gluteal tuberosity, proximally.

There are two further borders on the shaft in addition to the linea aspera: the lateral and medial borders. The shaft is divided into three surfaces by these three borders: anterior, medial, and lateral.

The medial side of the femur shaft somewhat lowers. By moving the knees closer to the body’s center of gravity, this improves stability. The proximal and distal parts of the shaft are posteriorly flattened, whereas the center has a circular cross-section.

The rough bone ridges on the posterior aspect of the femoral shaft are referred to as “linea aspera” (rough line in Latin).

This splits distally to generate the lateral and medial supracondylar lines. The popliteal surface is flat in between them.

The medial border of the linea aspera forms the pectineal line proximally. The lateral boundary gives rise to the gluteal tuberosity, which is where the gluteus maximus is attached.

Occasionally seen on the proximal femur, the third trochanter is a bony protrusion close to the superior border of the gluteal tuberosity. When it is there, it is occasionally continuous with the gluteal ridge and has an oblong, rounded, or conical shape.

The third trochanter is a small human structure whose prevalence varies between 17 and 72% among ethnic groups. It is commonly considered to be more common in girls than in males.

The distal part of the Femur bone

At the distal end of the femur are prominent medial and lateral condyles. An epicondyle protrudes from every condyle, serving as a point of attachment for the collateral ligaments. The intercondylar notch divides the lateral and medial condyles.

The thickest femoral extremity of the femur is its lower extremity, also known as the distal extremity, whereas the shortest femoral extremity is its upper extremity.

Although it has a slightly cuboid shape, its transverse diameter is bigger than its front-to-back (anteroposterior) diameter. It is made up of two condyles, which are oblong protrusions.

The patellar surface, a smooth, shallow articular depression, separates the somewhat protruding condyles anteriorly. They protrude significantly posteriorly, and there is a deep notch of the femur’s intercondylar fossa between them.

Lateral and medial condyles

- Rounded regions around the femur’s end. The tibia and the knee’s menisci are where the posterior and inferior surfaces articulate, whereas the front surface does so with the patella.

- While a flatter lateral condyle raises the possibility of patellar dislocation, a more prominent condyle helps to restrict the patella’s natural lateral motion.

- In terms of anteroposterior and transverse dimensions, the lateral condyle is wider and more pronounced. The longer medial condyle extends to a lower level when the femur is positioned with its body perpendicular.

- However, the lower surfaces of the two condyles almost entirely lie in the same horizontal plane when the femur is in its normal oblique orientation.

- The long axis of the lateral condyle is almost exactly anteroposteriorly, while the medial condyle travels backward and medially. As a result, the condyles are not exactly parallel to one another.

The lateral and medial epicondyles

- Elevated bones on the condyles’ non-articular regions. Of the two, the medial epicondyle is the bigger one.

- The medial and lateral collateral ligaments of the knee originate in their respective epicondyles.

Intercondylar fossa

- A deep groove on the back surface of the femur between the two condyles.

- The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) connects to the medial aspect of the lateral condyle, while the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) attaches to the medial aspect of the medial condyle.

- This structure has two aspects where intracapsular knee ligaments can be attached.

The intercondyloid fossa’s walls are made up of tiny, concave, rough opposing surfaces. The intercondyloid line, a ridge, limits this fossa above, while the central portion of the patellar surface’s posterior edge limits it below.

The anterior cruciate ligament of the knee joint is connected to an imprint on the higher and rear portion of the lateral wall of the fossa, while the posterior cruciate ligament is joined to the lower and front portion of the fossa’s medial wall.

The anterior, inferior, and posterior surfaces of the condyles are occupied by the articular surface of the lower end of the femur. Its anterior portion, referred to as the patellar surface, articulates with the patella.

It has two convexities the lateral being more prominent, larger, and extending higher than the medial as well as a median groove that descends to the intercondyloid fossa.

The epicondyle, an elevation, sits atop each condyle. The tibial collateral ligament of the knee joint is linked to the broad, convex medial epicondyle.

The adductor tubercle is located in its top portion, and a rough impression behind it is where the medial head of the gastrocnemius originates.

The fibular collateral ligament of the knee joint receives attachment from the lateral epicondyle, which is smaller and less noticeable than the medial.

Structure and function

The upper body’s weight is supported by the two femoral heads. The thick and robust sheath known as the capsular ligament encircles the proximal femur and acetabulum periosteum.

This ligament stabilizes the femoral head inside the pelvic acetabulum. The capsular ligament limits internal rotation while allowing external rotation.

The knee is a hinge joint made up of the proximal tibia and distal femur. The tibiofemoral articulation is stabilized and cushioned by the medial and lateral meniscus.

Valgus and varus deformities are prevented by the medial and lateral ligaments. The tibia’s anterior or posterior displacement is restricted by the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments in the knee joint, but the knee can still rotate to some extent.

The patellofemoral joint is used to extend the knee.

Since the femur is the only bone in the thigh, all muscles that apply force to the hip and knee joints link to it at this location.

The femur is also the source of some biarticular muscles, such as the gastrocnemius and plantaris muscles, which bridge two joints. There are twenty-three distinct muscles that either attach to or come from the femur.

The thigh’s cross-section displays three distinct fascial compartments, separated by fascia, and contains muscles. Tough connective tissue membranes divide these compartments, which are oriented around the femur.

These compartments each house a distinct set of muscles and have their own blood and nerve supplies. The anterior, medial, and posterior fascial compartments are the names given to these spaces.

Blood Supply and Lymphatic System

The femoral artery is the main blood channel that supplies the lower limbs. Though it is not the primary blood supply in maturity, the foveal artery branches off of the obturator artery, which passes through the ligamentum teres femoris and supplies blood to the femoral head.

The distal part of the femur and its shaft are supplied by the perforating branches of the deep femoral artery.

After navigating the ilioinguinal ligament, this artery is the main branch of the external iliac artery.

The femoral artery gives rise to the medial and lateral circumflex arteries. These veins form important anastomotic linkages with the obturator artery, a branch of the internal iliac artery that delivers blood to the femoral head.

Though not the main blood supply, the foveal artery, a branch of the obturator artery that passes through the ligamentum teres femoris, provides the femoral head with supporting blood flow.

At the level of the lesser trochanter, the femoral artery divides into the deep and superficial femoral arteries. The distal part of the femur and the shaft are supplied by the perforating branches of the deep femoral artery.

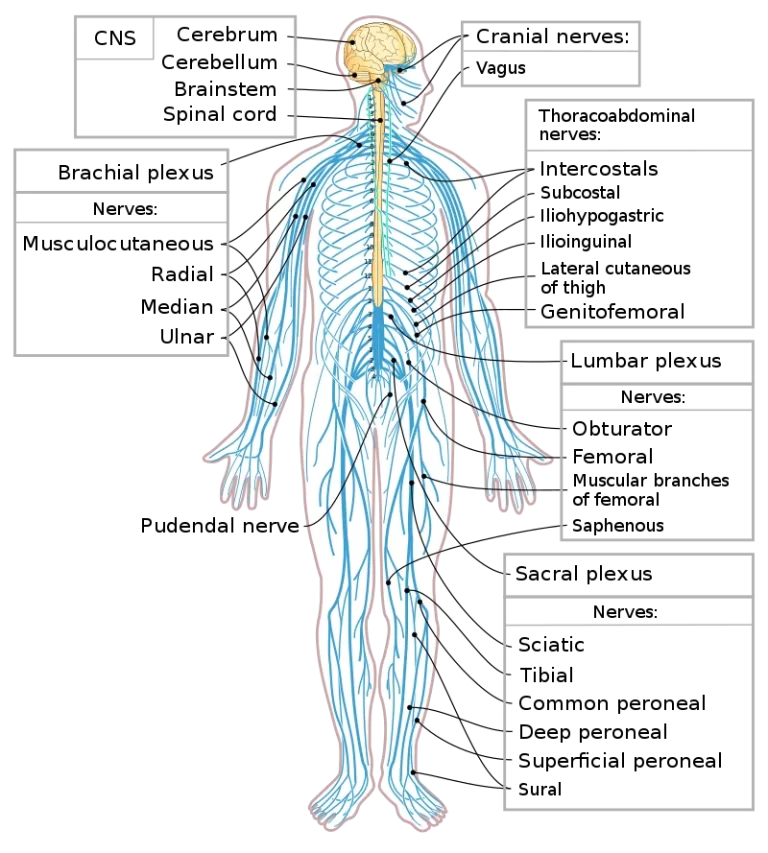

Nerves around the bone

The Femur’s Innervation

The longest bones, the big flat bones, and the vertebrae have the highest level of Osseus sensory innervation.

The periosteum is densely innervated for sensory function by the surrounding nerves. Sensory nerves in bone and marrow follow blood arteries. They can be found in the perivascular areas around Haversian canals.

The proximally located femoral and obturator nerves supply the hip joint, which in turn innervate the periosteum of the femur. The distal periosteum is supplied by the common fibular, femoral, obturator, and tibial nerves, which innervate the knee.

There is a discernible nutritional foramen located medial to the linea aspera on the posterior portion of the femur.

Nerves Innervating the Femur-Associated Muscles

Anterior Branches

The ventral rami of L2, L3, and L4 give origin to the femoral nerve. This nerve originates in the psoas major muscle and runs beneath the inguinal ligament, between the iliac and psoas major muscles.

The femoral canal, femoral vein, and femoral artery are the order in which the nerve is found. For structures that transition from the lateral to the medial aspect, the acronym NAVEL serves as a helpful reminder of this arrangement.

The femoralx2 nerve is denoted by N, the femoral artery by A, the femoral vein by V, and the empty space with lymphatics (femoral canal with the Cloquet lymph node) by EL.

Branches of the femoral nerve supply the knee and hip joints. The vastus lateralis, vastus intermedius, vastus medialis, rectus femoris, sartorius, and pectineus are innervated by the femoral nerve in the quadriceps femoris.

The nerve supplies the leg’s medial surface with sensory branches that travel via the anterior and intermediate femoral nerves, as well as the saphenous nerve, which travels through Hunter’s subsartorial (adductor) canal.

The nerve over the medial malleolus may be tested by the physician. Injuries to the femoral nerve can occur during orthopedic and pelvic surgeries. Another possibility of harm is the implantation of femoral arterial catheters and femoral nerve blocks. An additional source of risk is longer surgical procedures.

- Lateral cutaneous nerve of thigh

The ventral rami of L2 and L3 of the lumbar plexus give birth to the lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh, also known as the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve.

At the anterior superior iliac spine, the nerve crosses the iliacus and travels under the inguinal ligament. The nerve will occasionally go through the inguinal ligament.

The lateral thigh’s skin is supplied by this nerve, and injuries to the nerve cause meralgia paresthetica. Pregnancy, obesity, and compression from tight, low-fitting clothing can all result in nerve lesions.

Although it is a sensory nerve, damage to it can cause excruciating agony.

- Obturator Nerve

The primary innervation of the medial compartment is provided by the obturator nerve, which also transports axons from the L2, L3, and L4 lumbar ventral rami.

The adductor brevis separates the two divisions of the obturator nerve, which travels through the obturator foramen. The adductor longus, adductor brevis, gracilis, and occasionally the pectineus are supplied by the anterior division.

The cutaneous branch of the obturator nerve, which supplies a portion of L2 and L3 on the medial thigh, is where the nerve stops.

The anterior part of the adductor magnus, the adductor brevis, and the anterior aspect of the obturator externus are innervated by the posterior division.

The tibial division of the sciatic nerve innervates the posterior part of the adductor magnus, which is also innervated by the hamstring muscles. Endometriosis can cause injury to the obturator nerve, albeit this is uncommon.

Posterior Branches

- Superior Gluteal Nerve

The larger sciatic foramen allows the sacral plexus to cross across the piriformis and give rise to the superior gluteal nerve (L4-S1).

It supplies the tensor fasciae latae in addition to the gluteus medius and gluteus minimus muscles. The hip joint receives sensory branches from the superior gluteal nerve.

- Inferior Gluteal Nerve

The sciatic plexus gives rise to the inferior gluteal nerve (L5-S2), which innervates the gluteus maximus by passing via the greater sciatic foramen beneath the piriformis.

The ability to extend the thigh at the hip will be lost if this nerve or muscle is damaged. When the patient is trying to get out of a sitting position or climb a staircase, they will be particularly aware of the deficit (as the patient tries to push the body to the level of the next step).

- Posterior Cutaneous Nerve of the Thigh

The posterior thigh is innervated by the posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh, also known as the posterior cutaneous femoral nerve (S1–S3), a direct branch of the sacral plexus.

The piriformis muscle is where the nerve enters the larger sciatic foramen. The skin of the buttock, thigh, and calf is innervated by the posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh.

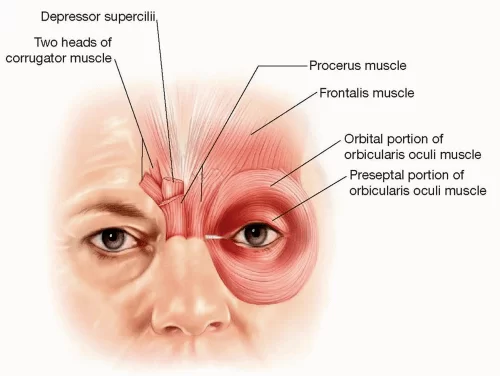

The thigh muscles are made up of the gluteal, medial, posterior, and anterior compartments.

Muscle attachment of the bone

Anterior compartment

The muscles that make up the anterior compartment are mostly involved in knee extension and hip flexion. The iliopsoas, pectineus, and sartorius muscles are examples of hip flexors.

The femoral nerve innervates every hip flexor save the iliopsoas. The strongest hip flexor is the iliopsoas muscle, which is made up of the iliacus and psoas major muscles.

- The iliacus

After emerging from the iliac fossa, iliac crest, and ala of the sacrum, the iliacus inserts on the lesser trochanter. The iliacus is supplied with nerves by the femoral nerve (L2-L3).

- The psoas

The psoas muscle emerges from the lateral part of the T12-L5 vertebrae and attaches with the iliacus on the lesser trochanter of the femur.

The ventral rami of L1–L3 innervate the iliacus. The iliopsoas is the hip’s strongest thigh flexor when combined.

- The pectineus

The pectineus originates from the superior pubic ramus and inserts on the pectineal line of the femur. Innervated by the femoral nerve, the pectineus helps rotate the medial thigh and serves as a hip flexor.

- The sartorius

inserts on the medial surface of the tibia, forming the spine of the iliac bone.

The word “sartor” is Latin for “tailor,” which makes sense given that they frequently cuff pants or hem skirts while seated cross-legged on the ground.

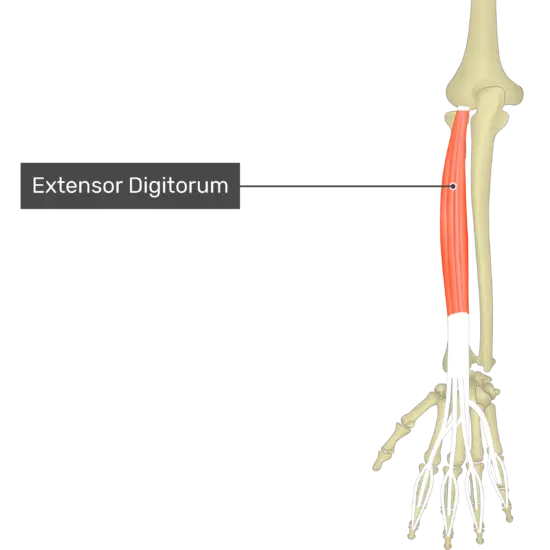

- The quadriceps femoris

The rectus femoris, vastus medialis, vastus intermedius, and vastus lateralis make up the quadriceps femoris muscle.

The patella, which is joined to the tibial tuberosity by the patellar tendon, is where all four muscles insert.

The femoral nerve innervates all of them (L2, L3, L4). It should be noted that the quadriceps femoris is innervated by the femoral nerve (L2, L3, L4), whilst the more proximal muscles in this compartment are innervated by the femoral nerve (L2, L3).

The anterior inferior iliac spine is the source of the rectus femoris. The medial lip of the linea aspera is the source of the vastus medialis muscle.

The greater trochanter and lateral lip of the linea aspera give rise to the vastus lateralis. The anterolateral femur is the source of the vastus intermedius.

The ventral rami has a higher value than the lower limb. The proximal-distal myotome principle is the name given to this.

Posterior Compartment

Most of the muscles in the posterior compartment are composed of the hip extensors and the knee flexors. The biceps femoris, semitendinosus, and semimembranosus are these muscles.

With the exception of the biceps femoris, the majority of the posterior thigh muscles are innervated by the tibial division of the sciatic nerve (L5, S1, S2).

- The biceps femoris

The biceps femoris has two heads: the long and short heads. The sciatic nerve’s tibial branch supplies the long head.

The short head is supplied by the common peroneal division of the sciatic nerve.

The gluteal region is organized by the layers of muscles that are superficial and deep.The superficial layer is composed of the gluteus maximus, medius, and minimus.

- The gluteus maximus

The posterior side of the ilium, sacrum, coccyx, and sacrotuberous ligament give rise to the gluteus maximus, which inserts on the gluteal tuberosity and iliotibial tract.

Gluteus maximus and other powerful thigh extensors are useful while climbing stairs or leaving a chair. While the iliopsoas bends the thigh at the hip to reach the next stair, the gluteus maximus pushes the body to new heights through power extension.

- The gluteus medius

The gluteus medius emerges from the posterior region of the ilium between the anterior and posterior gluteal lines and inserts on the lateral face of the greater trochanter.

The gluteus medius (L5, S1) is supply by the superior gluteal nerve.

The gluteus minimus on the posterior part of the ilium has a similar origin.

Both muscles abduct and twist the thigh laterally at the hip. Furthermore, when the opposing leg is raised off the ground, it prevents the pelvis from descending.

Tensor fasciae latae (TFL) inserts on the Gerdy tubercle of the tibia after emerging from the anterior superior iliac spine. The TFL is also supplied by the superior gluteal nerve (L5, S1).

The quadratus femoris, the superior and inferior gemellus muscles, the piriformis, and the obturator internus make up the deep layer.

- The piriformis

The piriformis muscle, which attaches to the superior border of the greater trochanter of the femur, is derived from the anterior sacrum and sacrotuberous ligament. S1, S2 ventral rami innervate the piriformis.

- The obturator internus

The obturator internus is formed from the bones that surround the obturator foramen. The L5, S1 area contains the nerve that innervates the obturator internus.

The greater trochanter’s medial surface is where the obturator internus inserts. When the thigh is extended, the deep muscles all rotate the thigh laterally.

They all abduct the flexed thigh at the hip and stabilize the femur head in the acetabulum.

- The superior and Inferior gemellus

The superior gemellus is innervated by the same neuron (L5, S1) that innervates the obturator internus.

The femur’s greater trochanter is where the inferior gemellus inserts after emerging from the ischial tuberosity. The inferior gemellus is innervated by the quadratus femoris nerve (L5, S1).

- The quadratus femoris

The ischial tuberosity is the source of the quadratus femoris, which inserts on the quadrate tubercle. This function is carried out by the nerve (L5, S1) that innervates the quadratus femoris.

The quadratus femoris turns the thigh laterally at the hip while stabilizing the femur head in the acetabulum. The external rotation of the hip is facilitated by these deeper and shorter gluteal muscles.

Medial compartment

Adduction of the thigh at the hip is the primary function of the muscles in the medial compartment of the thigh. The muscles of this compartment include the obturator externus, gracilis, adductor magnus, adductor longus, and adductor brevis. The obturator nerve provides the majority of innervation to the medial compartment.

- The adductor longus

The adductor longus emerges from the pubis and penetrates the middle region of the linea aspera. The obturator nerve (L2, L3, L4) innervates the adductor longus, which adducts the thigh.

- The adductor brevis

The adductor brevis inserts into the pectineal line and the linea aspera after leaving the pubis. The obturator nerve (L2, L3, L4) innervates the adductor brevis.

- The adductor magnus

The muscle known as the adductor magnus is intricate and has two innervations. The anterior half emerges from the ischiopubic ramus and inserts onto the linea aspera.

This muscle, an adductor of the thigh at the hip, is innervated by the obturator nerve.

The posterior part, a hamstring, is innervated by the tibial aspect of the sciatic nerve (L4) and arises from the ischial tuberosity. It inserts onto the adductor tubercle of the femur.

- The gracilis

As a portion of the pes anserine (goose’s foot) tendon, the gracilis inserts on the medial aspect of the tibia after emerging from the body and inferior ramus of the pubis.

The gracilis, which bends the thigh laterally and maintains the femur head in the acetabulum, is innervated by the obturator nerve (L2, L3).

- The obturator externus

The obturator externus exits the obturator foramen and inserts onto the trochanteric fossa of the femur.

The obturator nerve innervates the obturator externus, which turns the thigh laterally and maintains the femur head in the acetabulum (L3, L4).

Articulations

Proximal femur

With the acetabulum acting as the socket and the femoral head acting as the ball, the proximal femur articulates with the acetabulum of the pelvis.

Allows for movement in three planes at the hip: the frontal plane’s abduction and adduction, the sagittal plane’s flexion and extension, and the horizontal plane’s internal and external rotation.

Distal femur

The tibiofemoral joint is the result of the convex femoral condyles of the femur articulating with the condyles of the tibia distally.

There are two planes of movement in the tibiofemoral joint: the horizontal plane experiences internal and external rotation, while the sagittal plane experiences knee flexion and extension.

The patellofemoral joint

The patellofemoral joint is formed by the patella’s articulation with the femur’s intercondylar/trochlear groove. The articular surfaces of the patella and femur slide in response to knee flexion and extension.

The study of embryology

In the femur and lower limb, the lateral plate mesoderm cells are the first to differentiate into limb buds.

The lateral plate somatic mesoderm of the lower limb bud is where the femur begins.

The process by which bone replaces hyaline cartilage models is called endochondral ossification.

The process of intramembranous ossification, which results in articular cartilages and epiphyseal plates, lacks a cartilage model.

The lateral plate somatic mesoderm also produces the perimysium, epimysium, and tendons. The femur muscles are produced by the myotomic component of the somites.

The periosteum, which covers the femur, gets its nourishment from the blood supply that is close by.

The compact bone of the femur, which is the strongest in the middle third of the bone where stresses are highest, provides strength.

Clinical Anatomy

Hip Disorder in Adolescents

Overweight male teenagers are at a higher risk of developing a hip problem affecting the femoral head called slipping capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE). A superior and anterior displacement of the metaphysis with respect to the epiphysis is known as SCFE.

While idiopathic reasons are the most common, radiation therapy, renal insufficiency, and endocrine dysfunction have also been connected to SCFE. One common consequence of SCFE is femoroacetabular impingement.

Preventative treatment for SCFE is still controversial, despite the fact that early treatment with a single screw through the growth plate has been shown to prevent increased slippage.

Recently, the modified Dunn technique has been studied for severe SCFE. Under the modified Dunn procedure, the femoral head is screw fixated to immobilize it after the deformity is repaired by removing a wedge of the femoral neck.

With the modified Dunn surgery, persistent hip discomfort and avascular necrosis were typical post-surgical sequelae.

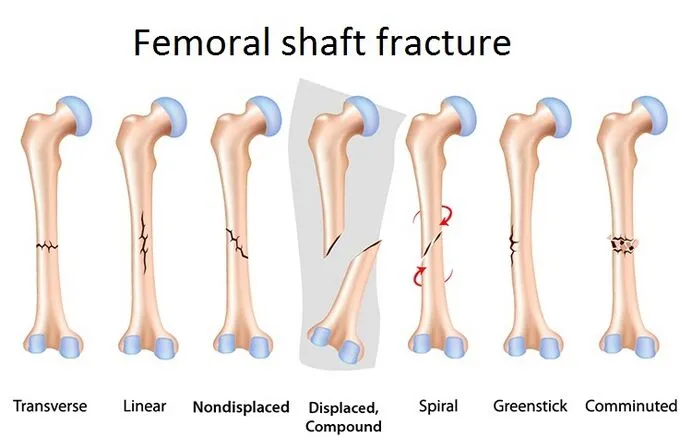

Fractures of the femur

When a bone breaks, clinicians refer to it as a bone fracture. Femurs are robust bones that are typically only fractured by severe traumas, falls, or auto accidents.

Among the signs of a fracture are:

- Pain.

- Swelling.

- Tenderness.

- Unable to fully extend the range of motion in your leg.

- Any discoloration or bruises.

- A lump or abnormality that doesn’t belong on your body.

Visit the emergency room as soon as you think you could have a fracture or have experienced trauma.

Fractures of the femoral shaft

Femoral shaft fractures are a very common injury that can be fatal and are frequently linked to polytrauma. If left untreated, they frequently arise from high-energy processes like auto accidents and cause limb shortening and abnormalities.

Based on the degree of comminution, femoral shaft fractures can be categorized using the Winquist and Hansen classification system.

These fractures have a bimodal distribution: younger people have more energy trauma, whereas older people experience lower energy trauma.

The degree of force involved determines the degree and complexity of fractures. They can be open or closed, transverse (moving horizontally across the shaft), oblique, spiral (caused by a twisting force), comminuted (resulting in three or more fragments of bone), or spiral.

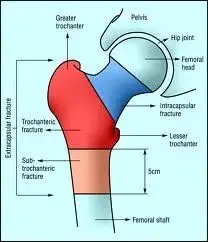

The neck of the femur (NOF) Fracture

One of the most common fractures that patients with orthopedic trauma teams and emergency departments see is a hip fracture.

Note that fractures to the hip and the neck of the femur (NOF) are related to the same kind of injury. A NOF fracture happens directly below the femur head.

During ADLs, the hip joint contact pressures can reach 509 kg, which is more than 500% of body weight (BW). Nevertheless, spontaneous fractures are rare in healthy people.

The majority of NOF fractures occur from falls among the elderly, and the incidence of NOF fractures is rising globally as the share of the old population grows.

The osteoporosis

Fractures that happen unexpectedly and suddenly are more likely to occur because osteoporosis weakens bones. Many people don’t realize they have osteoporosis until one of their bones breaks. Usually, there aren’t any overt signs.

Osteoporosis is more common in women, those over 50, and people assigned to the feminine gender at birth.

Schedule a bone density test with your physician; this will help prevent fractures by identifying osteoporosis early on.

Patellofemoral pain syndrome

Patellofemoral pain syndrome is the term for pain that surrounds and lies beneath your kneecap, or patella (PFPS). Sometimes people refer to it as runner’s knee or jumper’s knee. Anything that might cause PFPS, such as overusing your knees or breaking into new shoes. PFPS symptoms include:

The discomfort felt when bending your knee, such as when crouching or climbing stairs.

Discomfort after sitting with a bent knee for a while.

Your knee may pop or crackle when you go upstairs or stand up.

Discomfort that gets worse as you alter the sports equipment, playing surface, or level of exercise.

If you’re having any new knee pain, consult your healthcare physician.

Vascular changes

A disturbance in the blood flow to the femoral head causes Legg-Calve-Perthes disease (LCP), an uncommon pediatric illness. Among the symptoms include hip pain and limping.

Boys are five times more likely to have LCP, which often manifests around age 4 to 8. Twin research indicates that low social standing is one of the environmental factors that raises the risk of LCP.

LCP is also associated with congenital malformations such as Down syndrome, inguinal hernias, and genitourinary diseases. The treatment plan is determined by the patient’s age and disease stage.

Exercise, acupuncture, braces, bisphosphonates, and hip arthroscopy are among the available treatments for LCP.

FAQs

Why is it called femur?

Since the femur is Latin for “thigh,” people often refer to this bone as the “thigh bone.” The proximal end of the thigh bone, which is closest to the heart, is referred to as the femoral head. The ball portion of the hip joint is located here. The greater trochanter and neck are located beneath the head of the femur.

What is the femur shape?

It terminates at the knee when the bone widens and begins below the hip. This hollow area of the bone has rounded ends on both ends and is roughly an inch and a half thick. The femoral head and neck are located on the top end (proximal aspect) of the femur.

Do females have a femur?

Male femur mean length was 436.88 mm; female femur mean length was 402.38 mm. Males’ mean trochanteric oblique femur length was 423.78 mm, while females measured it at 387.18 mm. In males and females, the femur head’s mean vertical diameter was 43 mm and 38.19 mm, respectively.

Who is the head of the femur?

The femoral neck supports the femoral head, which is the most proximal part of the femur. It articulates with the pelvic acetabulum. The ligamentum teres attaches to the nearly spherical (two-thirds) femoral head by a medial depression called the fovea capitis femoris.

What is the blood supply of the femur?

The profunda femoris, the deep penetrating branch of the upper thigh, is a branch of the femoral artery, and it provides the majority of the blood flow to the head of the femur through the medial and lateral circumflex branches.

How strong is the femur bone?

For instance, the human femur bone’s ultimate compressive strength, measured during compression along its length, is 205 MPa (205 Million Pascals). The femur bone’s greatest tensile strength under tension is 135 MPa along its whole length.

Reference

- Femur | Definition, Function, Diagram, & Facts. (2023, December 1). Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/femur

- Chang, A. (2023, November 17). Anatomy, Bony Pelvis, and Lower Limb: Femur. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532982/

- Femur. (2023, December 27). Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Femur

- Femur. (n.d.). Physiopedia. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Femur

- The Femur – Proximal – Distal – Shaft – TeachMeAnatomy. (2020, November 13). TeachMeAnatomy. https://teachmeanatomy.info/lower-limb/bones/femur/

- Professional, C. C. M. (n.d.). Femur. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/22503-femur