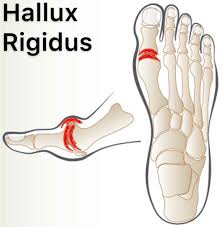

Hallux Rigidus

What is a Hallux Rigidus?

Hallux rigidus is a disorder of the joint located at the base of the big toe. It causes pain and stiffness in the joint, and with time, it gets increasingly harder to bend the toe.

Hallux is a Latin word that means the big toe, while rigidus indicates that the toe is rigid and cannot move. Hallux rigidus is actually a form of degenerative arthritis.

This disorder can be very troubling and even disabling since we use the big toe whenever we walk, stoop down, climb up, or even stand. Many patients confuse hallux rigidus with a bunion, which affects the same joint, but they are very different conditions requiring different treatment.

Because hallux rigidus is a progressive condition, the toe’s motion decreases as time goes on. In its earlier stage, when the motion of the big toe is only somewhat limited, the condition is called hallux limitus. But as the problem advances, the toe’s range of motion gradually decreases until it potentially reaches the end stage of rigidus, in which the big toe becomes stiff or what is sometimes called a frozen joint.

Hallux rigidus usually develops in adults between the ages of 30 and 60 years. No one knows why it appears in some people and not others. It may result from an injury to the toe that damages the articular cartilage or from differences in foot anatomy that increase stress on the joint. This condition occurs in approximately 1 in 40 patients over the age of 50.

The term Hallux Rigidus describes a limited arthrosis of the first MTP joint. It is an arthritic condition limited to the dorsal aspect of the first MTP joint. Also known as a dorsal bunion or Hallux Limitius, the condition is most commonly idiopathic (but may be associated with post-traumatic OCD of the metatarsal head) and is characterized by extensive dorsal osteophyte and dorsal third cartilage damage and loss. An associated synovitis may further aggravate the limited and painful ROM.

Classification of Hallux Limitus

Mild–

Objective findings-Near normal ROM, pain with forced hyper dorsiflexion, tender dorsal joint, minimal dorsal osteophyte.

Treatment-Symptomatic.

Moderate–

Objective findings-Painful, limited dorsiflexion, tender dorsal joint, osteophyte on the lateral radiograph.

Treatment-Symptomatic, consider early surgical repair.

Severe–

Objective findings, severely limited dorsiflexion, tender dorsal joint, large osteophyte on lateral radiograph, decreased joint space on AP radiograph.

Treatment-Symptomatic, consider surgical repair, dorsiflexion osteotomy.

End–stage–

Objective findings pain and limited motion, global arthrosis and osteophyte formation, with loss of joint space on all radiograph projections.

Treatment-Symptomatic, consider arthrodesis.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

The base of the the first MTP specifically is where degenerative arthritis is typically found. The joint is covered with articular cartilage, a shiny covering to protect the ends of the bones within the joint. As this covering wears, degeneration occurs until a bone is against bone. Bone spurs develop as part of this degenerative process and movement decreases. The normal range of motion is between 65 to 100 degrees.

Mechanism of Injury / Pathological Process of Hallux rigidus:

Hallux Rigidus is a progressive disorder where the great toe’s motion is decreased over time. Some causes are faulty function or biomechanics and structural abnormalities such as displaced sesamoid bones as a result of Hallux Valgus. Over time this leads to osteoarthritis and reduced range of movement in the joint.

In the MTP joint, as in any joint, the ends of the bones are covered by a smooth articular cartilage. If wear-and-tear or injury damages the articular cartilage, the raw bone ends can rub together. A bone spur, or overgrowth, may develop on the top of the bone. This overgrowth can prevent the toe from bending as much as it needs to when you walk. The result is a stiff big toe or hallux rigidus.

Symptoms of Hallux rigidus:

Pain, stiffness, and loss of motion are the some signs of hallux rigidus. Burning pain and paraesthesia can be present. Walking, standing, and wearing heels aggravate the pain. Symptoms are relieved by rest.

The normal dorsiflexion range of motion of the first MTP joint is at least 65 degrees showed a new standard of “normal” range of dorsiflexion range of motion of the great toe joint should now be set at approximately 45 degrees. However, this dorsiflexion range has only been verified for walking gait, not running.

Causes

Limited motion of the big toe caused by hallux rigidus. Common causes of hallux rigidus are faulty function (biomechanics) and structural abnormalities of the foot that can lead to osteoarthritis in the big toe joint. This type of arthritis—the kind that results from wear and tear—often develops in people who have defects that change the way their foot and big toe functions.

For example, those with fallen arches or excessive pronation (rolling in) of the ankles are susceptible to developing hallux rigidus. In some people, hallux rigidus runs in the family and is a result of inheriting a foot type that is prone to developing this condition. In other cases, it is associated with overuse, especially among people engaged in activities or jobs that increase the stress on the big toe, such as workers who often must stoop or squat.

Hallux rigidus can also result from an injury, such as stubbing your toe. Or it may be caused by inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis or gout. Your foot and ankle surgeon can determine the cause of your hallux rigidus and recommend the best treatment.

Symptoms

Early signs and symptoms include:

Pain and stiffness in the big toe during use (walking, standing, bending, etc.)

Pain and stiffness aggravated by cold, damp weather

Difficulty with certain activities (running, squatting)

Swelling and inflammation around the joint

As the disorder gets more serious, additional symptoms may develop, including:

Pain, even during rest

Difficulty wearing shoes because bone spurs (overgrowths) develop

Dull pain in the hip, knee, or lower back due to changes in the way you walk

Limping (in severe cases)

Deformity

Rigid deformity of the big toe caused by Hallux Rigidus

Diagnosis

The sooner this condition is diagnosed, the easier it is to treat. Therefore, the best time to see a foot and ankle surgeon is when you first notice symptoms. If you wait until bone spurs develop, your condition is likely to be more difficult to manage.

In diagnosing hallux rigidus, the surgeon will examine your feet and move the toe to determine its range of motion. X-rays help determine how much arthritis is present as well as to evaluate any bone spurs or other abnormalities that may have formed.

Diagnostic Procedures

Weight bearing, anterior posterior, and lateral radiographs are usually needed to examine the joint. Often non-uniform joint space narrowing, widening, or flattening of the 1st MT head is seen. Subchondral sclerosis or cysts, horseshoe shaped osteophytes, lateral greater than medial osteophytes, and sesamoid hypertrophy may be seen.

The Hattrup and johnson’s Classification:

Hattrup and Johnson described a radiographic classification that has become standard, and in fact correlates quite well with the Regnauld grading:

- Grade 1: mild to moderate osteophytes formation but good joint space preservation

- Grade 2: moderate osteophyte formation with joint space narrowing and subchondral sclerosis

- Grade 3: marked osteophyte formation and loss of the visible joint space, with or without subchondral cyst formation

The Coughlin and Shurnass classification:

Grade 0:

Dorsiflexion 40-60°

Normal radiography

No pain

Grade 1

Dorsiflexion 30-40°

Dorsal osteophytes

Minimal/ no other joint changes

Grade 2

Dorsiflexion 10-30°

Mild to moderate joint narrowing or sclerosis

Osteophytes

Grade 3

Dorsiflexion less than 10°

Severe radiographic changes

Constant moderate to severe pain in extremities

Grade 4

Stiff joint

Severe changes with loose bodies and osteochondritis dissecans

Differential Diagnosis

Turf toe, fracture, gout, and rheumatoid arthritis could be some other causes of pain and stiffness in the 1st MTP joint.

Examination

- Look for other features of systemic arthropathy.

- Assess the overall foot shape, range of ankle dorsiflexion and function of the other foot joints Identify sites of tenderness – is the osteophyte symptomatic?

- Evaluate the severity of rigidity and the residual arc of movement. Is pain provoked mainly by dorsiflexion, plantarflexion, or throughout the range of movement?

- Check the alignment of the great toe, looking for IPJ hyperextension or hallux rigidus with valgus. Are there any lesser ray problems?

Clinical examination

Patients with hallux rigidus may present with altered gait patterns or pain on the lateral aspect of the foot. This is secondary to the attempt to reduce loading on the first MTP joint. Patients may also report limitations on wearing certain types of shoes due to dorsal osteophytes on the first metatarsal head and proximal phalanx. Concurrently, patients may experience numbness along the medial border of the great toe as the osteophytes can compress on the dorsomedial cutaneous nerve.

Physical examination

The foot must be evaluated in the seated and standing positions. The standing position will provide information regarding the dynamic alignment and function of the hallux. The seated position will relax the soft tissues and help assess ROM.

The first MTP joint is often tender dorsally, with often palpable osteophytes. Since the dorsal osteophytes may compress on the dorsomedial cutaneous nerve, sensation deficits and vascular function of the foot should be recorded.

Evaluating the ROM of the first MTP joint is critical as it may be an indicator of the severity of arthritis. The most common finding is a decreased passive and active ROM, most notably in dorsiflexion. In milder forms of hallux rigidus, pain during passive ROM usually occurs at or near the endpoints of flexion. However, pain in midrange motion indicates the more diffuse level of arthritic change in the joint.

ROM has typically been measured clinically using a goniometer. However, clinical goniometric measurement has been proven to be unreliable and difficult to reproduce in a standardized manner as it is affected by various factors including instrumentation and different patient types. A new reliable and reproducible method for measuring the hallux MTP ROM using dynamic X-rays. There was a significant difference between clinical ROM and radiographic ROM, with clinical dorsiflexion being equal to or less than the radiographic dorsiflexion. The difference was more pronounced in patients with a clinical dorsiflexion of less than 30 degrees. In addition, radiographic measurements of hallux dorsiflexion had excellent intra- and interobserver reliability.

The hallux interphalangeal (IP) joint should also be carefully examined. Should the joint also be arthritic, the surgeon should avoid fusing both IP and MTP joints to prevent abnormal gait patterns.

Radiographic examination

Weight-bearing anteroposterior (AP), lateral, and oblique views of the affected foot should be obtained. The degree of joint space narrowing is best observed on the oblique view. In later stages of hallux rigidus, osteophytic formation can be observed in the periarticular area of the metatarsal head and proximal phalanx. It is important to note that the dorsal osteophytes can obstruct the AP view of the joint.

This can lead to false impression of more severe osteoarthritis. Deland and Williams noted that osteophytes can also mislead the actual amount of joint space narrowing as it can help maintain the joint space. The dorsal aspect of the joint is generally affected first. Other radiographic findings include joint sclerosis and subchondral cysts. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) images should not be necessary to diagnose the condition or to plan surgery.

Outcome Measures

- Visual analog scales

- AOFAS (American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society) scores

- Subjective self-assessment score

- MTP dorsiflexion

- MTP total motion

Treatment of Hallux rigidus:

Nonsurgical Treatment

In many cases, early treatment may prevent or postpone the need for surgery in the future. Treatment for mild or moderate cases of hallux rigidus may include:

- Shoe modifications. Shoes with a large toe box put less pressure on your toe. Stiff or rocker-bottom soles may also be recommended.

- Orthotic devices. Custom orthotic devices may improve foot function.

- Medications. Oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen, may be recommended to reduce pain and inflammation.

- Injection therapy. Injections of corticosteroids may reduce inflammation and pain.

- Physical therapy. Ultrasound therapy or other physical therapy modalities may be undertaken to provide temporary relief.

Physiotherapy treatment for hallux rigidus.

Physiotherapy is focused on reducing pain and is often performed in conjunction with podiatry treatment. If conservative management techniques fail to provide relief, the patient may be referred for a surgical opinion.

Physiotherapy treatment can include:

- Wax therapy

- Stretching programmes

- Orthotics

- Electrotherapy

- Corrective Strengthening Exercises of Weak Muscles

- Taping

Acute stage-Days 0-6

- Rest, ice bath, contrast bath, whirlpool, and ultrasound for pain, inflammation, and joint stiffness.

- Joint mobilization followed by gentle, passive, and active ROM.

- Isometrics for muscles around MTP joint.

- Isolated plantar fascia stretches with a can or a golf ball.

- Protective taping and shoe modifications for continued weight-bearing activities.

Sub-acute stage-Weeks 1-6

- Modalities to decrease inflammation and joint stiffness.

- Emphasis on Joint mobilization and active and passive methods for increasing flexibility and ROM.

- Gastrocnemius stretching.

- Plantar fascia stretching.

- Progressive strengthening with towel scrunches, toe pick-up activities, seated toe, and ankle dorsiflexion with progression to standing, seated isolated toe dorsiflexion with progression to standing, seated supination and pronation with progression to standing.

- Balance activities including BAPS board.

- Cross-training activities (slide board, water running, cycling) to maintain aerobic fitness.

Return to sport stage-Week 7

- Continued use of protective insert or taping.

- Continued ROM and strength exercises.

- Running to progress within the limits of a pain-free schedule.

- Plyometric and cutting program, with progression.

Surgical therapy in Hallux rigidus:

The indication for surgery is intractable pain isolated to the first metatarsophalangeal joint that is refractory to shoe modification, use of rigid shoe inserts, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, and modification of activities. The choice depends on the stage of involvement, the limitations in the range of motion, the activity level of the patient, and the preferences of the surgeon and patient.

Types of surgery include:

Cheiloectomy – A procedure to remove bone spurs at the top of the joint allowing greater toe extension and improved walking. Usually beneficial for mild to moderate disease with less than 50% of joints affected usually grade 1 and grade 2.

In some cases bone spurs that form on the top of the joint can bump together when the big toe bends upward, or extends. This causes a problem when walking because the big toe needs to bend upward when the foot is behind the body, in order to take the next step. The constant irritation when the bone spurs bump together leads to pain and difficulty walking.

A cheilectomy is a procedure to remove the bone spurs at the top of the joint so that they don’t bump together when the toe extends. This allows the toe to bend better and reduces the amount of pain while walking. To perform a cheilectomy, an incision is made along the top of the joint. The bone spurs that are blocking the joint from extending are identified and removed from both the bones that make up the joint. A little extra bone may be taken off to ensure that nothing rubs when the hallux is raised. The skin is closed and allowed to heal.

Dorsiflexion phalangeal osteotomy – In patients with a reasonable range of motion, a dorsal wedge osteotomy of the phalanx increases dorsiflexion at a theoretical cost of loss of plantar flexion. Mild to moderate cases occasionally require this procedure.

Metatarsal Osteotomy – a slice is removed from the dorsal limb to slide the head down and proximally. The Place for these procedures is uncertain and more complex than cheilectomies. These procedures are intended for use in early hallux rigidus

Excision Arthroplasty or Keller procedure– The Keller procedure is when resection of the base of the proximal phalanx and soft-tissue reconstruction is performed with the intention to decompress the joint and improve pain and range of movement. The Keller procedure may lead to great toe weakness, cock-up deformity and metatarsalgia.

MTP Arthrodesis – This is a procedure is performed to fuse the joint surfaces and is a favored procedure. Suitable for most cases and severity but usually grades 3 and 4 are recommended. Suitable as salvage when other procedures have failed (for example Keller procedure) Arthrodesis of the first MPJ consistently shows superior results and patient satisfaction in comparison to other surgical options. While cheilectomy may be beneficial for the early stages of hallux rigidus, arthrodesis of the first MPJ appears to be the best option for the relief of symptoms with stage III and stage IV hallux rigidus in active, athletic patients.

Joint Fusion– Many surgeons prefer arthrodesis, or fusion, of the MTP joint to relieve the pain. To fuse a joint means to encourage the two bones that form a joint to grow together and become one bone. To perform a fusion, an incision is made into the MTP joint. The joint surfaces are removed. The two surfaces are then fixed with either a metal pin or screw, with the toe turned slightly upward to allow for walking. The bones are then allowed to fuse. The fusion usually takes about three months to become solid.This results in a joint that no longer moves. Wearing a rocker-soled shoe is usually necessary following a fusion to improve your gait.

Artificial joint replacement– A procedure to replace joint surfaces with a plastic or metal surface. This technique of soft-tissue interposition arthroplasty gave excellent pain relief and reliable function of the hallux, and is an alternative treatment to MTP arthrodesis in select cases of severe hallux rigidus. The downside to this is the joint may not last a life time and there is currently no study documenting the long-term performance of any first MTP joint prosthesis in running athletes

After Surgery

Your post-surgical treatment will depend on what you have done with your toe. Generally, however, it will take about eight weeks before the bones and soft tissues are well healed. You may be placed in a wooden-soled shoe or a cast during this period to protect the bones while they heal. You will probably need crutches briefly; a physiotherapist at the hospital will help you learn to use your crutches and ensure that you are safe using them on level ground as well as stairs.

The incision is protected with a bandage or dressing for about one week after surgery. The stitches are generally removed in 10 to 14 days. However, if your surgeon used sutures that dissolve, you won’t need to have the stitches taken out.

During your follow-up visits, X-rays will probably be taken so that the surgeon can follow the healing of the bones if a fusion is performed. X-rays are also important if an artificial joint is used to make sure the implant is properly aligned and positioned.

Post-Surgical Rehabilitation

The timing of rehabilitation depends on exactly what has been done in your individual case.

Depending on what surgery you have had your therapist may use modalities such as interferential current(IFT), ultrasound, ice, or moist heat to reduce the pain. Gentle massage and light mobilizations or traction to the joints of the toe and foot can also assist with pain and any ongoing swelling in addition to improving mobility of the joints. If your joint has been fused, then mobilizations of the fused joint, of course, are of no use, but other joints around the area may require this treatment.

Both the range of motion and strength in your foot (and likely your entire low limb) will be decreased due to the surgical procedure that has been done as well as your altered gait pattern post surgery. Your physiotherapist will prescribe stretching exercises for your toe, foot and calf, as well as strengthening exercises for the same areas. Strengthening exercises may be as simple as picking up marbles with your toes or may include the use of exercise tubing or small elastics. Since the alignment of the foot is maintained by not only the muscles of the foot, but also those of the hip, knee, and core area, we will also prescribe strengthening exercises for these areas. Maintaining proper alignment is particularly important to avoid further problems with the foot and surgical toe. If exercises are too painful on land your therapist may recommend that you do them in a pool, your home tub, or even a pail of warm water so long as your surgical wound is ready for water immersion.

As you get stronger your therapist will prescribe more difficult exercises such standing on your foot on an uneven surface, repetitively raising up onto your toes, and then raising up onto your toes and maintaining this position to improve muscle endurance. These exercises will improve muscle strength and endurance but also improve your foot’s proprioception, or ability to know where it is in space without you having to look at it. Once your foot is mobile and strong enough, we will encourage you to do a short period of uphill walking which helps to both improve the range of motion in your toe and also increase the strength of the foot and calf.

it is important for you to maintain your cardiovascular fitness while you are recovering from the surgery for your toe. Although heavy endurance walking or running will not be recommended until a bit further on in your recovery, in the early stages you can still use a stationary cycle, a rowing machine, or get into the pool once the surgical wound is healed to partake in water running or water aerobics. A weight program for your upper extremities, core area, and other leg may be continued early on in your recovery if you have clearance from your doctor and provided that all exercises are in the seated position and do not put stress through your healing toe.

The therapist will ensure that you are walking with a proper gait. Being that each person takes thousands of steps per day, if you are walking inefficiently or with poor alignment, it can quickly and easily lead to further pain and problems in your foot or up into your ankle, knee, hip, or even low back. A period on crutches or in a cast or brace often leads in itself to a poor walking pattern that carries on once you are off the crutches or out of the brace or cast. Your physiotherapist will address any abnormal walking pattern and teach you how to correct it. The strengthening exercises that we prescribe, as mentioned above, will be important to gain enough strength and control to walk normally after your surgery.

During your follow-up visits with your surgeon, X-rays are usually taken so that the surgeon can follow the healing of the bones and determine how much correction has been achieved.

Generally rehabilitation after surgery for hallux rigidus goes extremely well.

Hallux Rigidus Massage

Roll in the direction of your heel by making tiny circular movements around the inside edge of your foot. Once you’ve reached a sensitive location, apply more pressure and continue massaging the area until you sense the tension leaving. Roll for another minute or so.

TAPING FOR HALLUX RIGIDUS

How can I avoid having a hallux rigidus?

Although it’s unlikely that you can stop hallux rigidus from occurring, you might be able to slow down its progress if you:

- Keep your big toe joint flexible by exercising.

- After vigorous exercise, give your joints some rest; never continue to play despite pain.

- Put on shoes that fit properly and leave adequate room between your toes.

Prognosis

You can resume your regular activities by reducing pain and inflammation with the appropriate medication. You can still be active even after some hallux rigidus procedures that limit your toe bending capacity. You will receive instructions from your surgeon or provider about what to do and what not to do.

Can hallux rigidus be cured?

Usually, surgery is the only technique for treating hallux rigidus permanently. However, the majority of patients with hallux rigidus are able to control their symptoms with a mix of nonsurgical interventions.

Conclusion

Speak with your healthcare practitioner if you experience pain in your big toe joint. Treatment for hallux rigidus can be more effective the sooner it is diagnosed. The majority of people can control their symptoms with nonsurgical therapies alone.

However, surgery may be helpful if chronic pain interferes with your life. There are various alternatives for surgery for hallux rigidus. Together, you and your surgeon will go over your options and determine which course of action is best for you.

4 Comments