Hamstring Muscle Injury

Introduction: Hamstring Muscle Injury

Hamstring muscle injury — such as a “pulled hamstring” — occur frequently in athletes. They are especially common in athletes who participate in sports that require sprinting, such as track, soccer, and basketball.

Hamstring injuries can also occur in recreational sports such as water-skiing and bull riding, where the knee is forcefully fully extended during injury.

A pulled hamstring or strain is an injury to one or more of the muscles at the back of the thigh. Most hamstring injuries respond well to simple, nonsurgical treatments.

Anatomy of Hamstring Muscle :

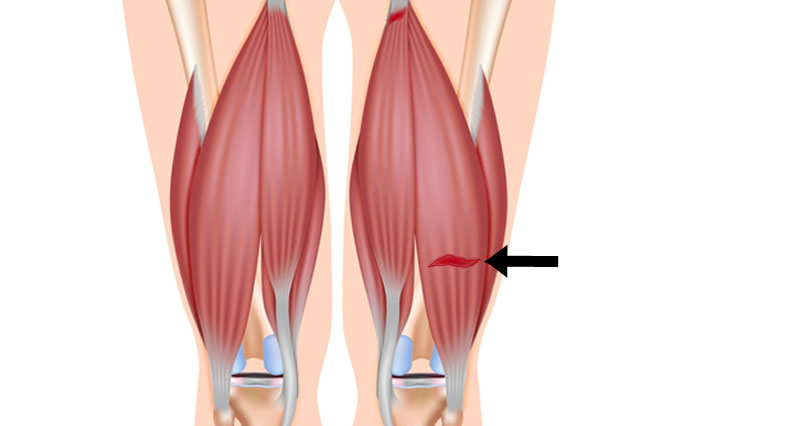

The hamstring muscles run down the back of the thigh. There are three hamstring muscles:

- Semitendinosus

- Semimembranosus

- Biceps femoris

They start at the bottom of the pelvis at a place called the ischial tuberosity. They cross the knee joint and end at the lower leg. Hamstring muscle fibers join with the tough, connective tissue of the hamstring tendons near the points where the tendons attach to bones.

Muscle Action of Hamstring Muscle

The hamstring muscle group helps you extend your leg straight back and bend your knee.

Description : Hamstring Muscle Injury

A hamstring strain can be a pull, a partial tear, or a complete tear.

Muscle strains are graded according to their severity. A grade 1 strain is mild and usually heals readily; a grade 3 strain is a complete tear of the muscle that may take months to heal.

Most hamstring injuries occur in the thick, central part of the muscle or where the muscle fibers join tendon fibers.

In the most severe hamstring injuries, the tendon tears completely away from the bone. It may even pull a piece of bone away with it. This is called an avulsion injury.

Epidemiology/Etiology:

The cause of a hamstring muscle strain is often obscure. In the second half of the swing phase, the hamstrings are at their greatest length and at this moment, they generate maximum tension.In this phase, hamstrings contract eccentrically to decelerate flexion of the hip and extension of the lower leg. At this point, a peak is reached in the activity of the muscle spindles in the hamstrings.

A strong contraction of the hamstring and relaxation of the quadriceps is needed. A breakdown in the coordination between these opposite muscles can be a cause for the hamstring to tear.The greatest musculotendon stretch is incurred by the biceps femoris, which may contribute to its tendency to be more often injured than the other 2 hamstring muscles (semimembranosus and semitendinosus) during high-speed running.

A strong contraction of the hamstring and relaxation of the quadriceps is needed. A breakdown in the coordination between these opposite muscles can be a cause for the hamstring to tear.The greatest musculotendon stretch is incurred by the biceps femoris, which may contribute to its tendency to be more often injured than the other 2 hamstring muscles (semimembranosus and semitendinosus) during high-speed running.

Which are the Cause of Hamstring Muscle Injury ?

Muscle Overload

- Muscle overload is the main cause of hamstring muscle strain. This can happen when the muscle is stretched beyond its capacity or challenged with a sudden load.

- Hamstring muscle strains often occur when the muscle lengthens as it contracts, or shortens. Although it sounds contradictory, this happens when you extend a muscle while it is weighted, or loaded. This is called an “eccentric contraction.”

- During sprinting, the hamstring muscles contract eccentrically as the back leg is straightened and the toes are used to push off and move forward. The hamstring muscles are not only lengthened at this point in the stride, but they are also loaded — with body weight as well as the force required for forward motion.

- Like strains, hamstring tendon avulsions are also caused by large, sudden loads.

Risk Factors in Hamstring Muscle Injury:

- Several factors can make it more likely you will have a muscle strain, including:

- Muscle tightness. Tight muscles are vulnerable to strain. Athletes should follow a year-round program of daily stretching exercises.

- Muscle imbalance. When one muscle group is much stronger than its opposing muscle group, the imbalance can lead to a strain. This frequently happens with the hamstring muscles. The quadriceps muscles at the front of the thigh are usually more powerful. During high-speed activities, the hamstring may become fatigued faster than the quadriceps. This fatigue can lead to a strain.

- Poor conditioning. If your muscles are weak, they are less able to cope with the stress of exercise and are more likely to be injured.

- Muscle fatigue. Fatigue reduces the energy-absorbing capabilities of muscle, making them more susceptible to injury.

- Choice of activity. Anyone can experience hamstring strain, but those especially at risk are:

- Athletes who participate in sports like football, soccer, basketball

- Runners or sprinters

- Dancers

- Older athletes whose exercise program is primarily walking

- Adolescent athletes who are still growing

- Hamstring strains occur more often in adolescents because bones and muscles do not grow at the same rate. During a growth spurt, a child’s bones may grow faster than the muscles. The growing bone pulls the muscle tight. A sudden jump, stretch, or impact can tear the muscle away from its connection to the bone.

Predisposing Factors/Risk Factors:

- Older age

- Previous hamstring injury

- Limited hamstring flexibility

- Increased fatigue

- Poor core stability

- Strength imbalance

- Ethnicity

- Previous calf injury

- Previous substantial knee injury

- Osteitis pubis

- Increased quadriceps flexibility was inversely associated with hamstring strain incidence in a group of amateur Australian Rules footballers

- Players presenting certain polymorphisms, IGF2 and CCL2 (specifically its allelic form GG), might be more vulnerable to severe injuries and should be involved in specific prevention programmes

- Tight hip flexors

- previously associated lumbar spine abnormalities. Kicking and executing abdominal strengthening exercises with straight legs have been identified as possible contributory causes of lordosis. The anatomical reason seems to be that the iliopsoas muscle group is primarily involved in kicking and straight leg raising or straight leg sit-up exercises and contributes to strengthening this muscle’. Therefore, it is possible that certain athletic activities and training methods that exacerbate postural defects may also predispose the player to injury.

- During activities like running and kicking, hamstring will lengthen with concurrent hip flexion and knee extension, this lengthening may reach the mechanical limits of the muscle or lead to the accumulation of microscopic muscle damage.There is a possibility that hamstring injuries may arise secondary to the potential uncoordinated contraction of biceps femoris muscle resulting from dual nerve supply.

- Excessive anterior pelvic tilt will place the hamstring muscle group at longer lengths and this may increase the risk of strain injury.

Symptoms in Hamstring Muscle Injury:

If you strain your hamstring while sprinting in full stride, you will notice a sudden, sharp pain in the back of your thigh. It will cause you to come to a quick stop, and either hop on your good leg or fall.

Additional symptoms may include:

- Swelling during the first few hours after injury

- Bruising or discoloration of the back of your leg below the knee over the first few days

- Weakness in your hamstring that can persist for weeks

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation

Hamstring strain results in a sudden, minimal to severe pain in the posterior thigh. Also, a “popping” or tearing impression can be described.Sometimes swelling and ecchymosis are possible but they may be delayed for several days after the injury occurs. Rarely symptoms are numbness, tingling, and distal extremity weakness. These symptoms require further investigation into sciatic nerve irritation. Large hematoma or scar tissue can be caused by complete tears and avulsion injuries.

Other possible symptoms:

- Pain

- Tenderness

- Loss of motion

- Decreased strength on isometric contraction

- Decreased length of the hamstrings Hamstring strains are categorised in 3 groups, according to the amount of pain, weakness, and loss of motion.

- Grade 1 (mild): just a few fibres of the muscle are damaged or have ruptured. This rarely influences the muscle’s power and endurance. Pain and sensitivity usually happen the day after the injury (depends from person to person). Normal patient complaints are stiffness on the posterior side of the leg. Patients can walk fine. There can be a small swelling, but the knee can still bend normally.

- Grade 2 (medium): approximately half of the fibres are torn. Symptoms are acute pain, swelling and a mild case of function loss. The walk of the patient will be influenced. Pain can be reproduced by applying precision on the hamstring muscle or bending the knee against resistance.

- Grade 3 (severe): ranging from more than half of the fibres ruptured to complete rupture of the muscle. Both the muscle belly and the tendon can suffer from this injury. It causes massive swelling and pain. The function of the hamstring muscle can’t be performed anymore and the muscle shows great weakness.

Doctor Examination

Patient History and Physical Examination

People with hamstring strains often see a doctor because of a sudden pain in the back of the thigh that occurred when exercising.

During the physical examination, your doctor will ask about the injury and check your thigh for tenderness or bruising. He or she will palpate, or press, the back of your thigh to see if there is pain, weakness, swelling, or a more severe muscle injury.

Examination:

Running gait: The physical examination begins with an examination of the running gait. Patients with a hamstring strain usually show a shortened walking gait. Swelling and ecchymosis aren’t always detectable at the initial stage of the injury because they often appear several days after the initial injury.

Observation: The physical examination also exists of visible examination. The posterior thigh is inspected for asymmetry, swelling, ecchymosis and deformity.

Palpation: Palpation of the posterior thigh is useful for identifying the specific region injured through pain provocation, as well as determining the presence/absence of a palpable defect in the musculotendon unit. With the patient positioned prone, repeated knee flexion-extension movements without resistance through a small range of motion may assist in identifying the location of the individual hamstring muscles and tendons. With the knee maintained in full extension, the point of maximum pain with palpation can be determined and located relative to the ischial tuberosity, in addition to measuring the total length of the painful region. The total length, width and the distance between ischial tuberosity and the area with maximal pain are measured in centemeters. While both of these measures are used, only the location of the point of maximum pain (relative to the ischial tuberosity) is associated with the convalescent period. That is, the more proximal the site of maximum pain, the greater the time needed to return to pre-injury level.The proximity to the ischial tuberosity is believed to reflect the extent of involvement of the proximal tendon of the injured muscle, and therefore a greater recovery period.

Range of motion :Range of motion tests should consider both the hip and knee joints. Passive straight leg raise (hip) and active knee extension test (knee) are commonly used in succession to estimate hamstring flexibility and maximum length.Typical hamstring length should allow the hip to flex 80° during the passive straight leg raise and the knee to extend to 20° on the active knee extension test. When assessing post-injury muscle length, the extent of joint motion available should be based on the onset of discomfort or stiffness reported by the patient. In the acutely injured athlete, these tests are often limited by pain and thus may not provide an accurate assessment of musculotendon extensibility. Once again, a bilateral comparison is recommended.

Hip flexibility :The hip flexion test combined a passive unilateral straight leg raise test (SLR) with pain estimation according to the Borg CR-10 scale. The sprinters were placed supine with the pelvis and contralateral leg fixed with straps. A standard flexometer was placed 10 cm cranial to the base of the patella. The foot was plantar flexed and the investigator slowly(approximately 30 degree) raised the leg with the knee straight until the subject estimated a 3 (“moderate pain”) on the Borg CR-10 scale (0 = no pain and 10 = maximal pain). The hip flexion angle at this point was recorded, and the greatest angle of three repetitions was taken as the test result for Range of Motion (ROM). Values of the injured leg were expressed as a percentage of the uninjured leg for comparisons within and between groups. No warm-up preceded the flexibility measurements.

Knee flexion strength : Isometric knee flexion strength was measured with the sprinter in a prone position and the pelvis and the contralateral leg fixed.A dynamometer was placed at the ankle, perpendicular to the lower leg. The foot was in plantar flexion and the knee in an extended position. Three maximal voluntary isometric knee flexion contractions were performed, each with gradually increasing effort. Each contraction lasted 3 s with 30 s of rest in-between. The highest force value was taken as the test result for strength. Attempts to bias the medial or lateral hamstrings by internal or external rotation of the lower leg, respectively, during strength testing may assist in the determination of the involved muscles.

Imaging Tests

Imaging tests that may help your doctor confirm your diagnosis include:

X-rays. : An X-ray can show your doctor whether you have a hamstring tendon avulsion. This is when the injured tendon has pulled away a small piece of bone.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). :This study can create better images of soft tissues like the hamstring muscles. It can help your doctor determine the degree of your injury.

Ultrasound (US): this kind of imaging is used a lot because it is a cheap method. It is also a good method because it has the ability to image muscles dynamically. A negative point about Ultrasound is that it needs a skilled and experienced clinician.

MRI study was done to distinguish between two main groups of muscle injuries: Injury by Direct or Indirect trauma. Within the group of injuries due to indirect trauma, the classification brings the concept of functional and structural lesions. Functional muscle injuries present alterations without macroscopic evidence of fiber tear. These lesions have multifactorial causes and are grouped into subgroups that reflect their clinical origin, such as overload or neuromuscular disorders. Structural muscle injuries are those whose MRI study presents macroscopic evidence of fiber tear, i.e., structural damage. They are usually located in the Musculotendinous junction, as these areas have biomechanical weak points.

Type of injury : Direct

Definition :

Contusion: blunt trauma from external factors, with intact muscle tissue

Laceration: blunt trauma from an external factor with muscular rupture

MRI : Hematoma

Type of injury : Indirect :Functional

Definition :

fatigue-induced muscle disorder Muscle stiffness

1B: delayed onset muscle soreness Acute inflammatory pain

Type 2: muscle disorder of neuromuscular origin

2A: spine-related neuromuscular muscle disorder Increased muscle tone due to neurological disorder

2B: muscle-related neuromuscular muscle disorder Increased muscle tone due to altered neuromuscular control

MRI : Negative

Negative or isolated edema

Type of injury : Structural

Definition :

Type 3: Partial muscle tear

3A: minor partial muscle tear: tear involving a small area of the maximal muscle diameter

3B: moderate partial muscle tear: tear involving moderate area of maximum muscle diameter

Type 4: (sub)total muscle tear with avulsion:

Involvement of the entire muscle diameter, muscle defect

MRI : Fiber rupture

Retraction and hematoma

Complete discontinuation of fibers

Differential Diagnosis

On examining the patient, the physiotherapist possibly has to differentiate between different injuries e.g. adductor strains, avulsion injury, lumbosacral referred pain syndrome, piriformis syndrome, sacroiliac dysfunction, sciatica, Hamstring tendinitis and ischial bursitis.

Other sources of posterior thigh pain could also be confused with hamstring strains and should be considered during the examination process. Specific tests and imaging are used to asses and exclude those different pain source possibilities.

Sciatic nerve mobility limitations can contribute to posterior thigh pain and adverse neural tension could in some cases be the only source of pain without any particular muscular injury. In certain cases it is difficult to determinate whether it is the Hamstrings or other muscle groups like hip adductors (eg. M. Gracilis and M. Adductor Magnus and Longus.) that are injured due to their proximity. Sometimes imaging procedures may be required to determinate the exact location of the injury.

Other conditions with similar presentations as hamstring strains are strained popliteus muscle, tendonitis at either origin of the gastrocnemius, sprained posterior cruciate ligament, apophysitis-pain in ischial tuberosity, Lumbar spine disorders and lesions of the upper tibiofibular joint.

Medical Management

Surgical intervention is an extremely rare procedure after a hamstring strain. Only in case of a complete rupture of the hamstrings, surgery is recommended. Almost all patients believed that they had improved with surgery.

Treatment

Treatment of hamstring strains will vary depending on the type of injury you have, its severity, and your own needs and expectations.

The goal of any treatment — nonsurgical or surgical — is to help you return to all the activities you enjoy. The primary objective of physical therapy and the rehabilitation program is to restore the patient’s functions to the highest possible degree and/or to return the athlete to sport at the former level of performance and this with minimal risk of re-injury.

Hamstring strain injuries remain a challenge for both athletes and clinicians, given their high incidence rate, slow healing, and persistent symptoms. Moreover, nearly one-third of these injuries recur within the first year following a return to sport, with subsequent injuries often being more severe than the original.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Most hamstring strains heal very well with simple, nonsurgical treatment.

RICE. The RICE protocol is effective for most sports-related injuries. RICE stands for Rest, Ice, Compression, and Elevation.

Rest: Take a break from the activity that caused the strain. Your doctor may recommend that you use crutches to avoid putting weight on your leg.

Ice: Use cold packs for 20 minutes at a time, several times a day. Do not apply ice directly to the skin.

Compression: To prevent additional swelling and blood loss, wear an elastic compression bandage.

Elevation: To reduce swelling, recline and put your leg up higher than your heart while resting.

Immobilization: Your doctor may recommend you wear a knee splint for a brief time. This will keep your leg in a neutral position to help it heal.

Physiotherapy in Hamstring Muscle Injury :

Once the initial pain and swelling has settled down, physical therapy can begin. Specific exercises can restore range of motion and strength.

A therapy program focuses first on flexibility. Gentle stretches will improve your range of motion. As healing progresses, strengthening exercises will gradually be added to your program. Your doctor will discuss with you when it is safe to return to sports activity.

Stretches and Strengthening exercise:

Hamstring stretch:

Step 1 Stand next to an exercise bench. Place one leg on the bench. Stand tall and move your shoulders down.

Step 2 Slightly bend your standing leg and hinge at the waist. Once you feel a stretch behind your lifted thigh, stop and hold this position for the recommended time.

Wall Hamstring Stretch

- Place one foot (and leg) on the wall and try to push your knee straight.

- Hold for 30 to 45 seconds.

- Gently release the stretch.

- Repeat with your other leg against the wall.

Slump stretch

Slump stretching is achieved when sitting in a slouched position (ie, with thoracic and lumbar flexion and a posterior pelvic tilt) and actively flexing one’s cervical spine as far as possible while remaining comfortable.

Chair lift:

Slowly raise both hips off the floor. Hold for 2 seconds and lower slowly. Do 3 sets of 15. After your hamstrings have become stronger and you feel your leg is stable, you can begin strengthening the quadriceps (the muscles in the front of the thigh) by doing lunges.

Prone hip extension

To perform, lay face down with your hands under your forehead. Make sure you adopt a neutral spine posture lightly activate your abdominals. Squeeze your glutes while continuing to breath normally, then slowly extend 1 leg off the floor without arching or rotating the spine. Either do some reps on the same leg and the switch legs, or do 1 rep per leg at a time. Make sure you focus on the glute squeeze and do not let it go while doing the movements. Also make sure you do not rotate your pelvis or hyperextend your lower back.

Lunges

A lunge is a single-leg bodyweight exercise that works your hips, glutes, quads, hamstrings, and core and the hard-to-reach muscles of your inner thighs.

Lunges can help you develop lower-body strength and endurance. They’re also a great beginner move. When done correctly, lunges can effectively target your lower-body muscles without placing added strain on your joints.

- Stand tall with feet hip-width apart. Engage your core.

- Take a big step forward with right leg. Start to shift your weight forward so heel hits the floor first.

- Lower your body until right thigh is parallel to the floor and right shin is vertical. It’s OK if knee shifts forward a little as long as it doesn’t go past right toe. If mobility allows, lightly tap left knee to the floor while keeping weight in right heel.

- Press into right heel to drive back up to starting position.

- Repeat on the other side.

Standing hamstring curl

The standing hamstring curl is a bodyweight exercise that tones your hamstring muscles. It’s an ideal workout for improving balance and leg strength.

To do a standing hamstring curl:

- Stand with your feet hip-width apart. Place your hands on your waist or on a chair for balance. Shift your weight onto your left leg.

- Slowly bend your right knee, bringing your heel toward your butt. Keep your thighs parallel.

- Slowly lower your foot.

- Complete 12 to 15 reps.

- Repeat with the other leg.

Seated hamstring curl

This exercise is done with a resistance band around your lower legs. Your hamstrings will have to work extra hard to move your heels against resistance.

To do a seated hamstring curl:

- Tie the ends of a resistance band to a sturdy object, such as an exercise machine or piece of furniture. Sit in front of the band. Place the loop around one of your heels and keep your feet together.

- Bend your knee to pull your heel back, stopping when you can’t pull any further.

- Extend your knee to return to starting position.

- Complete 12 to 15 reps. Then repeat on the other leg.3. Prone hamstring curl

Like the seated hamstring curl, the prone version adds resistance to your lower legs. This engages your hamstrings when you bend your knees.

To do a prone hamstring curl:

- Anchor the ends of a resistance band to a sturdy object. Lie down on your stomach with your feet hip-width apart. Place the band around one heel and flex your ankle.

- Bend your knee to pull your heel toward your butt, keeping your thighs and hips on the mat.

- Stop when you can’t pull any further. Return to starting position.

- Complete 12 to 15 reps.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery is most often performed for tendon avulsion injuries, where the tendon has pulled completely away from the bone. Tears from the pelvis (proximal tendon avulsions) are more common than tears from the shinbone (distal tendon avulsions).

Surgery may also be needed to repair a complete tear within the muscle.

Procedure. To repair a tendon avulsion, your surgeon must pull the hamstring muscle back into place and remove any scar tissue. Then the tendon is reattached to the bone using large stitches or staples.

A complete tear within the muscle is sewn back together using stitches.

Rehabilitation. After surgery, you will need to keep weight off of your leg to protect the repair. In addition to using crutches, you may need a brace that keeps your hamstring in a relaxed position. How long you will need these aids will depend on the type of injury you have.Your physical therapy program will begin with gentle stretches to improve flexibility and range of motion. Strengthening exercises will gradually be added to your plan.

Rehabilitation for a proximal hamstring reattachment typically takes at least 6 months, due to the severity of the injury. Distal hamstring reattachment require approximately 3 months of rehabilitation before returning to athletic activities.

Recovery

- Most people who injure their hamstrings will recover full function after completing a rehabilitation plan. Early treatment with a plan that includes the RICE protocol and physical therapy has been shown to result in better function and quicker return to sports.

- To prevent reinjuring your hamstring, be sure to follow your doctor’s treatment plan. Return to sports only after your doctor has given you the go-ahead. Reinjuring your hamstring increases your risk of permanent damage. This can result in a chronic condition.

Prevention tips:

As hamstring strains can be nasty injuries, athletes should work hard to avoid them. After all, healing a hamstring strain is much harder than preventing it. Here are some tips:

- Warm up before and stretch after physical activity.

- Boost the intensity of your physical activity slowly — no more than a 10% increase a week.

- Stop exercising if you feel pain in the back of your thigh.

- Stretch and strengthen hamstrings as a preventive measure.

9 Comments