Hemifacial Spasm (Face Twitching)

What is a Hemifacial Spasm?

Hemifacial spasm is a neuromuscular disorder characterized by involuntary contractions or twitching of the muscles on one side of the face. This condition typically begins with intermittent spasms around the eye or mouth but can progress to involve other facial muscles as well.

The ipsilateral facial nerve (seventh cranial nerve), which innervates the facial muscles on one side of the face, causes paroxysmal, involuntary twitches that are the hallmark of hemifacial spasm (HFS).

Shorter or longer contractions of the facial expression muscles are caused by the abnormal involuntary stimulation of the peripheral facial nerve. A subtype of peripheral (neuromuscular) movement dysfunction is thought to be HFS. As the name implies, the disease is nearly usually unilateral, with the exception of a small percentage of instances (2.6% of all HFS cases) where bilateral face muscle involvement is visible.

This condition typically doesn’t result in a major physical handicap, but it frequently creates social shame, which worsens the patient’s mental problems.

Causes of Hemifacial Spasm

Primary Hemifacial Spasm

The most frequent cause of HFS is compression of the facial nerve by an abnormal or ectatic artery as it leaves the brainstem. The branches of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery, posterior inferior cerebellar artery, and vestibular artery are among the common abnormal vascular abnormalities that cause compression of the face nerve root.

The root-exit zone, which is the place where the facial nerve leaves the brainstem, is only covered by the arachnoid membrane in the absence of the epineurium. Between the nerve fascicles, there are no connective tissue septa. This is also the area where peripheral and central myelin, which are produced by Schwann cells and oligodendrocytes, respectively, meet. Due to these special characteristics, the nerve is vulnerable to any kind of stimulation or compression.

Secondary Hemifacial Spasm

The following causes can lead to HFS secondary to them:

- Trauma

- Late-stage Bell’s palsy sequelae

- structural abnormalities along the facial nerve’s path, particularly a benign tumor pressing on the nerve’s intracranial portion

- Angiomas, arterio-venous fistulas, intracranial arterial aneurysms, and arteriovenous abnormalities

- Ear infections (cholesteatoma, otitis media) and mastoid

- tumors of the parotid gland

- Other anatomical abnormalities of the posterior cerebral fossa, including Chiari malformation

- brainstem lesions, such as multiple sclerosis demyelinating plaques

Epidemiology

Given that the estimated global prevalence of HFS is 14.5 per 100,000 women and 7.4 per 100,000 men, indicating that women are twice as likely as men to have HFS, HFS is a rare disorder. Studies have shown that, for unclear reasons, the prevalence of individuals in the Asian population is marginally higher than that of the Caucasian population. Though few case reports of familial HFS exist in the scientific literature, most cases of HFS are irregular.

Particularly in cases with main HFS, the condition frequently manifests itself in adulthood during the fourth or sixth decade of life. As seen in the majority of documented cases, the left side is typically affected more than the right. According to research, 40% of people with HFS also have hypertension.

Pathophysiology

The main pathophysiologic mechanism of HFS is chronic irritation of the proximal nerve segment at the root-exit zone and the facial nerve fascicle. The arachnoid membrane alone covers the root-exit zone, where the facial nerve leaves the brainstem, in the absence of the epineurium. According to published research, the most prevalent cause of HFS is compression of the facial nerve root at the intersection of the peripheral segment (root exit/entry zone) and central segment (point of exit from brainstem) by aberrant/ectatic blood vessels.

Between the nerve fascicles, there are no septa of connective tissue. This is also the area where peripheral and central myelin, which are produced by Schwann cells and oligodendrocytes, respectively, meet. Due to these unique characteristics, the nerve is vulnerable to any kind of stimulation or compression. The pathophysiological process by which facial nerve compression results in HFS has been explained by a number of ideas.

Nerve Origin Hypothesis (Peripheral Theory)

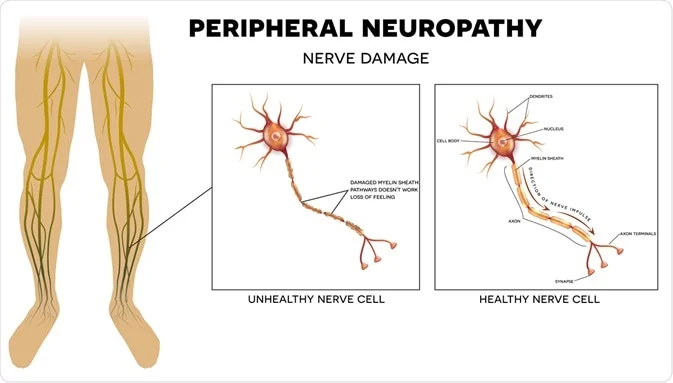

According to this idea, the unusually excessive firing of the facial nerve is caused by the ephaptic transmission of impulses or the lateral spread of excitation to adjacent nerve fibers; this firing is caused by the demyelination of the facial nerve at the compression site. Insulating tissue called myelin is crucial to nerve impulse conduction because it stops abnormal lateral spread, which can lead to ectopic impulse transmission and HFS.

Nuclear Origin Hypothesis (Central Theory)

When peripheral afferent facial nerve fibers are irritated, the central facial nerve nucleus receives abnormal signals, which causes the nucleus to fire abnormally. The affected side’s facial muscles contract involuntarily due to this hyperexcitability of the facial nucleus.

Hemifacial Spasm Secondary to Bell Palsy

Although the clinical presentation of bell palsy is similar to other HFS, the pathogenesis is distinct. Strictly speaking, this is a synkinesis rather than a true HFS. Pathological axonal damage is present in more severe cases of Bell palsy. During the healing process, axon regeneration might not take place along the original branches.

As a result, an abnormal reinnervation process may occur where the branch to the orbicularis oculi regenerates to the orbicularis oris. Syncinesis is the term for the phenomena when the orbicularis oris muscle and other lower facial muscles contract concurrently when the eye blinks, or vice versa as the orbicularis oculi muscle does.

Symptoms of Hemifacial Spasm

Hemifacial spasms frequently cause the following symptoms: jerking of the face’s muscles, which are typically:

- on a single facial side.

- not under our control.

- without pain.

These contractions, which are just movements of the muscles, frequently begin in the eyelid. On the same side of the face, they can then proceed to the mouth and cheek. Hemifacial spasms first occur intermittently. However, over the course of months or years, they happen nearly always.

It can rarely affect both sides of the face. But the twitching doesn’t happen simultaneously on both sides of the face.

Traditionally, the orbicularis oculi is involved in the involuntary tonic/clonic contractions of one side of the face, which results in the ipsilateral eye closing briefly, intermittently, and without pain. Eye twitches and rare eyebrow-raising are related to this involuntary activity. Also called the “other Babinski sign,” it shares the name of Joseph Babinski, who first identified it in 1905. “Other Babinski sign” is pathognomic for HFS and aids in differentiating it from blepharospasm-related eye twitching/closure, which is characterized by the absence of browlift.

The perioral muscles (orbicularis oris, mentalis, zygomaticus major, platysma) and other lower face muscles are affected by irregular tonic/clonic contractions, which progressively worsen over months to years. Similar to blepharospasm, there is frequently an involuntarily forced closure of the eyelids when the symptoms intensify. When making a differential diagnosis, the “other Babinski sign” will be quite useful.

When secondary HFS worsens, the lower and upper faces experience synchronized, intermittent contractions that finally result in prolonged spasms. One feature that sets hemifacial spasms apart from the majority of movement disorders is the continuous spasms that occur during sleep. This could put the person at risk for insomnia and sleep disturbances.

In more severe cases, the pull of tightened muscles on one side is visible, causing facial deviation/asymmetry and grimacing. Muscle contraction on one side causes visible asymmetry in HFS. In rare cases of subsequent hemifacial spasms, unusual symptoms are recorded, such as ear pain, hearing loss, and an unusual clicking sound in the ear (caused by stapedius involvement). The usual aggravating factors for symptoms are anxiety, food, weariness, and stress. The spasm or twitching is reduced by using relaxation techniques or just touching the face.

Hemifacial Spasm Following Bell Palsy

Some individuals may experience involuntary twitching of the side of their face affected by the previous Bell palsy after a more severe case. With its involuntary contraction of the facial muscles, this twitching is similar to HFS. The mechanism and clinical manifestation, however, are entirely distinct. Following Bell palsy, abnormal reinnervation of the facial nerve causes synkinesis, an abnormal facial movement in which the orbicularis oris muscle or other lower facial muscles may contract concurrently with the eye’s blink, or vice versa as the orbicularis oculi.

Relationship between Hypertension and HFS

Studies’ findings show that 40% of people with HFS also have hypertension at the same time. As such, it is essential to determine whether the patient has hypertension.

Diagnosis

Clinical diagnosis of HFS is established by combining a thorough history with a local and neurological physical examination. Electrophysiological testing is rarely necessary because a clinical diagnosis is obtained instead. When it is challenging to differentiate the condition clinically from facial myokymia, blepharospasm, complex partial motor seizures, or motor tics, an electromyogram may be utilized in the early stages of the illness.

Blink reflex testing reveals varied synkinesis and lateral spread as the diagnostic findings based on electrophysiological testing. When one branch of the facial nerve is stimulated, the facial muscles supplied by another branch contract. Facial twitching can be clinically associated with the high frequency (150-400 Hz) irregular, short motor unit potentials that are characteristic of needle electromyography.

A precise diagnosis is crucial because other illnesses might resemble HFS. Rule out an underlying structural lesion, particularly a benign tumor at the brainstem nerve root exit zone or close to the cerebellopontine angle, if there is a suspicion of facial nerve compression. The best diagnostic test to rule out lesions indicative of multiple sclerosis or structural problems that would require surgical therapy is a brain magnetic resonance imaging scan.

Generally speaking, magnetic resonance angiography or computed tomography are not recommended. The results of the magnetic resonance angiography and computed tomography scans will typically be unimpressive in the majority of primary HFS cases since even those without HFS frequently have vascular loops near the facial nerve. Only those patients who are scheduled for microvascular decompression procedures are eligible for magnetic resonance angiography. For the preoperative assessment of microvascular decompression, a 3D time-of-flight magnetic resonance angiography with high-resolution T2-weighted pictures would be particularly beneficial.

Treatment of Hemifacial Spasm

Reducing muscular contractions caused by abnormal impulse transmissions to nearby neurons—a condition known as ephaptic transmission—is the main objective of HFS treatment. The mode of treatment for this condition can be either medical or surgical, depending on the underlying cause and degree of severity.

Medical Treatment

Oral Drugs

Oral drugs have been the traditional method of treating HFS, particularly when it is mild and in its early stages. Oral drugs that are frequently prescribed include benzodiazepines (clonazepam), anticholinergics, baclofen, haloperidol, carbamazepine, and gabapentin, which are anticonvulsants.

There is some efficacy to these medications in reducing spasms, although the effects are not always constant. Adverse effects such as severe sedation, exhaustion, and dependence associated with long-term usage are the main drawbacks of most of these drugs. If a patient is not a suitable candidate for surgery and is hesitant to receive botox treatments, oral medicines may be the first line of treatment.

Botulinum Neurotoxin Injections

The development of botulinum neurotoxin, or botox, has completely changed how HFS is managed. Because of its effectiveness and low risk of side effects, botox injections are now the treatment of choice for both patients and doctors. According to multiple clinical research, 85% to 95% of patients saw significant symptom improvements after receiving Botox treatment. Prior to receiving botox treatment, a comprehensive evaluation is necessary to rule out any secondary reasons, such as tumors or vascular abnormalities.

The affected muscles, most typically the masseter, corrugator, frontalis, zygomaticus major, buccinators, and orbicularis oculi (upper and lower eyelids), are injected with Botox, a straightforward and noninvasive treatment. However, the patient should be advised that adverse events are modest and brief and may include ptosis, temporary bruising, swelling, facial asymmetry, asymmetric eyebrows, and facial weakness.

OnabotulinumtoxinA is the most often utilized botox used to treat HFS. Additional botox formulations that are sold commercially are abobotulinumtoxinA and rimabotulinumtoxinB. Botox operates on the presynaptic terminal at the neuromuscular junction, preventing the release of presynaptic neurotransmitter acetylcholine through a calcium-mediated pathway. This prevents nerve impulses from passing over the neuromuscular junction, temporarily paralyzing the supplied muscles. Usually lasting three to six months, this chemodenervation effect returns to baseline.

Botox is said to have a dual advantage in that it helps patients with HFS feel less depressed. According to the concept, there are two ways that Botox relieves depression. Firstly, by alleviating symptoms, less social shame results. The amygdala’s heightened activation can lead to anxiety and depression, therefore the other potential method involves decreasing this activation. Reduced trigeminal sensory input to the brainstem and amygdala results from Botox’s chemical denervation of nearby facial muscles, which stops afferent sensory information from reaching the trigeminal tract.

Dosage and Scheduling for Injections of Botoxin

Onabotulinum neurotoxin A is normally administered at a dose of 10–36 U. Repeated injections spaced three to six months between are required. Because long-term effects can vary, some doctors recommend variable dosing intervals of six to twenty weeks. After receiving a botox injection, symptoms start to improve three to six days later and peak two weeks later.

Surgical Treatment of Hemifacial Spasm

When HFS is severe and a patient is not responding to botox therapy, surgery is the only long-term cure that treats the underlying problem. Microvascular decompression is the preferred method because it releases the facial nerve from the abnormal vessel’s compression at the brainstem’s root exit zone.

The lateral spreading response is caused by the ephaptic transmission of nerve impulses to nearby neurons as a result of compression-related demyelination of the facial nerve root at the exit/entry zone, as was previously addressed in the electrophysiological findings. The lateral spreading response to nerve stimulation will go away when such compression is released. Preoperative visualization of the abnormal vessel may be enhanced by a high-resolution 3D time-of-flight magnetic resonance angiography combined with high-resolution T2-weighted imaging.

The typical success rate of microvascular decompression surgery is believed to be between 80% and 88% following the first year of operation.

Complications of Surgery

Every invasive operation has its share of problems. Aside from the hazards associated with anesthesia, this complex technique may cause temporary or permanent facial nerve palsy, hearing loss, CSF leaking, and recurrent episodes of symptoms. Patients who are asymptomatic for at least two years following surgery are at least 1% at risk of developing recurrent HFS.

Differential Diagnosis

A precise diagnosis is essential to the development of a successful HFS treatment strategy. Numerous conditions can resemble HFS. When a patient under 40 years old appears with HFS, doctors need to consider multiple sclerosis as a possibility. Nevertheless, this illness is rarely documented when it first manifests as HFS. The facial nerve roots may be affected by demyelinating plaques in the brain stem region, which can cause abnormal signaling and HFS.

Prognosis

Even though hemifacial spasm is known to have a continuously progressive history, up to 10% of individuals may experience an uncommon spontaneous remission. Counseling regarding this persistent but mostly benign disease is essential for the patient.

Assisting patients in realizing that receiving recurrent botox injections every three to six months is the most straightforward and successful form of therapy. Only in cases when the patient no longer desires recurring injections or when the HFS is not responding well to botox injections may microvascular surgery be considered.

Consultations

If microvascular decompressive surgery is being stated, a consultation with a neurovascular surgeon is recommended.

Education for Patients and Prevention

Given that HFS is linked to social shame, anxiety, and depression because of handicap, prompt diagnosis and treatment are crucial. Severe cases of continuous eye closure can be dangerous to the patient and anyone around them, especially when driving or using heavy machinery, as they can result in functional blindness.

Although injecting botox has been the go-to management technique because it works so well, there are two main downsides to this therapy: it is expensive and requires repeated surgeries. Patients who are thinking about surgery need to be well informed about the advantages and disadvantages of the complex and invasive microvascular decompression procedure that requires a craniotomy.

Additional Concerns

Important details about HFS to keep in mind are as follows:

HFS is defined as a recurring, uncontrollable, non-suppressible facial muscular contraction that occurs almost invariably unilaterally and lasts through sleep. The primary cause is typically a facial nerve compression caused by an ectatic or abnormal blood artery at the brainstem’s outflow.

Clinical diagnosis is typically made using the patient’s medical history and physical examination. Prior to therapy planning, EMG and magnetic resonance imaging are performed to determine or rule out the underlying cause.

Patients frequently experience severe social shame, anxiety, and sadness as a result of the illness. In the most extreme circumstances, functional blindness caused by abrupt, involuntary eye closure may pose a risk to both the patient and other people, especially when driving. A precise diagnosis, prompt treatment, and patient education are essential components in enhancing these patients’ quality of life.

With an 85% to 95% success rate and a low frequency of side effects, Botox is the preferred treatment for HFS. Botox, however, only provides temporary symptom alleviation. In the US, onabotulinumtoxinA is the most often utilized commercially available botox.

With an average success rate of 85%, microvascular decompression is the only therapy modality that treats the underlying cause and results in a full recovery.

Healthcare Teams

Despite being an uncommon movement disorder, doctors need to be aware of HFS since it can be mistaken for a number of other facial movement disorders, including motor tics, facial myokymia, and blepharospasm. Patients are frequently referred to neurologists or otolaryngologists by primary care physicians. Radiologists help in image interpretation.

Patients with this illness may be evaluated, treated, and educated by nurses with specialized training. Pharmacists can help with medication administration education, especially when it comes to polypharmacy. The interprofessional team is crucial to providing patients with HFS with the best possible care.

Patients and doctors both prefer the local botox injection as the preferred course of treatment. Just two excellent studies—one class II research and one class III study—show HFS as a sign that should be treated with botox, according to a systematic analysis of the literature. Botox should be made available as a therapy option for HFS, according to the evidence-based treatment guidelines published by the American Academy of Neurology.

Conclusion

A chronic neuromuscular disease is hemifacial spasm. You can’t control the twitching on one side of your face when you have a hemifacial spasm. Symptoms typically begin near the eyes and progress downhill. Although there is no cure, your symptoms can be managed with medication, injections of botulinum toxin, or surgery. Your physician and you can collaborate to determine the best course of action for you.