How Many Disc In Your Back

Introduction

There is a total of twenty-three discs within the human spine: six in the cervical region (neck), twelve in the thoracic region (middle back), and five in the lumbar region (lower back). The intervertebral disc (IVD) is the main in the normal functioning of the spine. It is a cushion of fibrocartilage or the principal joint between two vertebrae in the spinal column.

The intervertebral disc allows the spine to be flexible without sacrificing a good deal of strength. They also provide a shock-absorbing effect within the spine and/or prevent the vertebrae from grinding together. They comprise three major components: the inner, nucleus pulposus (NP), the outer, annulus (AF), and therefore the cartilaginous endplates that anchor the discs to adjacent vertebrae.

The disc also includes the anterior longitudinal ligament and posterior longitudinal ligament. The vertebral disc within the spine is an interesting and unique structure. Specific problems with any of those discs may prompt unique symptoms, including pain that originates within the disc itself or pain that is related to the disc pressing on a nearby nerve.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

The anatomy of a usual spinal disc includes the tough outer layer called the annulus fibrosus and the gelatinous inner layer called the nucleus pulposus. If tears occur within the annulus fibrosus, the nucleus pulposus may leak out. Discs are composed of two parts: a tough outer portion and a soft inner core, and therefore the configuration has been likened to that of a jelly doughnut.

There are 3 different distinctions for disc problems:

Disc protrusion: The disc’s outer wall remains intact, and therefore the disc protrudes 180 degrees or less of the disc’s circumference.

Bulging Disc: The disc’s outer wall remains intact, and therefore the disc protrudes more than 180 degrees of the disc’s circumference.

Herniated disc: the bulging disc’s outer wall tears, allowing the inner fluid to get out.

The intervertebral disc comprises three distinct components:

- A central nucleus pulposus (NP)

- A peripheral annulus fibrosus (AF)

- Two vertebral endplates (VEPs).

Nucleus Pulposus

A gel-like structure that sits in the middle of the intervertebral disc and accounts for much of the strength and flexibility of the spine. It is made of 66 % to 86 % of water with the remainder consisting of primarily type II collagen (it may also consist of type VI, IX, and XI) and proteoglycans. The proteoglycans include the larger aggrecan and versican that bind to mucopolysaccharide, as well as several small leucine-rich proteoglycans. The inner core (nucleus pulposus) contains a loose network of fibers suspended during a mucoprotein gel. Aggrecan is essentially responsible for retaining water within the nucleus pulposus. This structure also contains a small density of cells. While sparse, these cells generate extracellular matrix (ECM) products (aggrecan, type II collagen, etc.) and/or maintain the integrity of the nucleus pulposus.

Annulus Fibrosus Collagen

it comprises “lamellae” or concentric layers of collagen fibers. The fiber orientation of every layer of lamellae alternates and/or therefore allows effective resistance of multidirectional movements. The annulus fibrosus contains an inner and an outer portion. They differ primarily in their collagen composition. While both are primarily collagen, the outer annulus consists mostly of type I collagen, while the inner has predominantly type II. The inner annulus also comprises more proteoglycans than the inner. NB collagen Type I: skin, tendon, vasculature, organs, bone (the main component of the organic part of the bone) Type II: cartilage (the particular collagenous component of the cartilage and/or is more flexible).

Vertebral Endplate

A vertebral endplate is the transition region between a disc or the adjacent vertebra. The vertebral endplate is thin and comprised of collagen or porous bone, which allows for nutrients and limited numbers of blood to pass into the disc. If a vertebral endplate becomes injured and dysfunctional, fewer nutrients can get to the disc, which can accelerate disc degeneration. An upper and a lower cartilaginous endplate (each about 0.6 to 1 mm thick) cover the superior and inferior aspects of the disc.

The endplate permits diffusion and provides the most source of nutrition for the disc. The hyaline endplate is additionally the last part of the disc to wear through during severe disc degeneration. Movement in general seems to increase the number of nutrients that pass through the vertebral endplates into the discs. Living an active lifestyle, rather than being sedentary, can assist nourish the discs. While the intervertebral discs help provides cushioning and flexibility for the neck, muscle movements are directed by signals sent from the brain through the medulla spinalis and nerve roots. a Plates of cartilage that bind the disc to their respective vertebral bodies.

Each endplate covers almost the whole surface of the adjacent vertebral body; only a narrow rim of bone, knowns as the ring apophysis, around the perimeter of the vertebral body is left uncovered by cartilage. The portion of the vertebral body to which the cartilaginous endplate is applied is mentioned as the vertebral endplate. The endplate covers the nucleus pulposus in its entirety; peripherally it fails to hide the entire extent of the annulus fibrosus. The collagen fibrils of the inner lamellae of the annulus enter the endplate and merge with it, leading to all aspects of the nucleus being enclosed by a fibrous capsule.

Innervation

- The disc is innervated in the outer few millimeters of the annulus fibrosus.

- Only the outer third of the Annulus fibrosis is vascular and innervated in an exceedingly non-pathologic state. In aging or states of inflammation, both nerve growth and connective tissue growth are stimulated. Additionally, the connective tissue secretes inflammatory cytokines, which further increases sensitivity to pain sensations.

Vascular Supply and Nutrition

The intervertebral disc is essentially avascular, with no major arterial branches to the disc. The outer annular layers are supplied by little branches from metaphysical arteries. Only an outer annulus is vascularized. Blood vessels near the disc bone junction of the vertebral body in addition to those in the outer annulus supply the Nucleus pulposus and inner annulus. Glucose, oxygen, and/or other nutrients reach the avascular regions by diffusion. The identical process removes metabolites.

Vital functions

- Restricted IV joint motion.

- Contribution to stability.

- Resistance to axial, rotational, and bending load.

- Preservation of anatomic relationship.

- It provides cushioning for the vertebrae and reduces the strain caused by impact.

- They act as shock absorbers in the spine, positioned between every bony vertebra.

- They help protect the nerves that run down the spine or between the vertebrae.

- They act as tough ligaments that clap the vertebrae of the spine together.

- They are cartilaginous joints that allow for little mobility in the spine.

Biomechanic

Weight-bearing: The disc is subjected to various weights, including compressive, tensile, and shear stresses. During compressive loading, hydrostatic pressure develops within the Nucleus pulposus, which thereby disperses the forces towards the endplates in addition to the Annulus fibrosis. This mechanism slows the speed applied loads are transmitted to the adjacent vertebra, giving the disc its shock-absorbing abilities. Movement: The disc is additionally involved in permitting movements between vertebral bodies, which include:

- Axial compression and distraction;

- Flexion and extension;

- Axial rotation;

- Lateral flexion.

Nuclear migration: Asymmetric compressive weight on the disc can cause the NP to migrate in a direction opposite to the compression. For example, during forward bending (or flexion) of the lumbar spine, the nucleus pulposus migrates posteriorly or backward. Conversely, during backward bending (or extension), the nucleus is squeezed anteriorly or forwards. This concept is called the dynamic disc model. Although nucleus pulposus migration has been shown to behave predictably in asymptomatic discs, a variable pattern of migration occurs in people with symptomatic and/or degenerative Intervertebral discs.

Physiologic Variants

Disc thickness generally increases from rostral to caudal. The thickness of the discs relative to the size of the vertebral bodies is higher in the cervical and lumbar regions. This reflects the increase in the range of motion found in those regions. In the cervical and/or lumbar regions, the intervertebral discs are thicker anteriorly. This creates a secondary curvature of the spine in the cervical and lumbar lordoses.

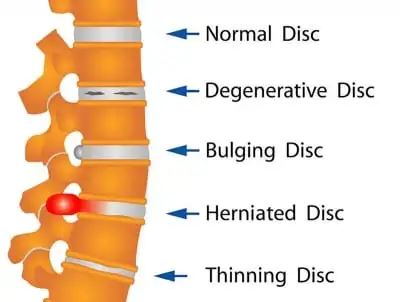

Pathology

There are several terms to explain the disc pathologies

- The Disc bulge is the circumference of the disc that extends beyond the vertebral bodies.

- Disc herniation involves the Nucleus pulposus. Disc herniation is important in that it may compress an adjacent spinal nerve. A ruptured intervertebral disc impinges upon the nerve associated with the inferior vertebrae (e.g., L4/L5 herniation affects the L5 nerve root). The most often site of disc herniation is at L5-S1, which can be due to the thinning of the posterior longitudinal ligament towards its caudal end. There are three subtypes of herniations:

- Disc protrusion is characterized by the width of the base of the protrusion being wider than the diameter of the disc material that is herniated.

- In disc extrusion, the Annulus fibrosis is damaged, allowing the Nucleus pulposus to herniate beyond the normal bounds of the disc. during this case, the herniated material produces a mushroom-like dome that is wider than the neck connecting it to the body of the Nucleus pulposus. The herniation can extend superior or inferiorly relative to the disc level.

- In disc sequestration, the herniated material breaks off from the body of the Nucleus pulposus.

- Disc desiccation is common in aging. It is brought about by the death of the cells that produce or maintain the ECM, including proteoglycans, like aggrecan. The Nucleus pulposus shrinks as the gelatinous form is replaced with fibrotic tissue, reducing its functionality, and leaving the AF supporting additional weight. This increased stress leads the Annulus fibrosis to compensate by increasing in size. The resulting flattened disc reduces mobility and should impinge on spinal nerves leading to pain or weakness. It is thought to be due to proteoglycan breakdown, which decreases the water-retaining properties of the Nucleus pulposus.

- NB: Significant research has been put into the means of replacing or re-growing the intervertebral discs. The several methods include the replacement of discs with synthetic materials, stem cell therapy, and gene therapy.

Additional Points

There are no intervertebral discs between C1 and C2, which is exclusive to the spine. there are two major ligaments that support the intervertebral discs. The anterior longitudinal ligament may be broadband that covers the anterolateral surface of the spine from the foramen magnum in the skull to the sacrum. This ligament assists the spine in preventing hyperextension and prevents intervertebral disk herniation in the anterolateral direction. The posterior longitudinal ligament covers the posterior aspect of the vertebral bodies, within the spinal canal, and serves mainly to stop a posterior herniation of the intervertebral discs, and is, therefore, to blame for most herniations being in the postero-lateral direction.

Disc Degeneration

Over time, spinal discs dehydrate and become stiffer, causing the disc to be less ready to adjust to compression. While this is often a natural aging process, because the disc degenerates in some individuals, it can become painful. The most likely reason for this is that the degeneration may produce micromotion instability or the inflammatory proteins (the soft inner core of the disc) probably leak out of the disc space and inflame the various nerve or nerve fibers in and surrounding the disc. A few times a twisting injury damages the disc or starts a cascade of events that leads to degeneration. The spinal disc itself has not had any type of blood supply. Without a blood supply, the disc does not have a way to repair itself, and/or the pain created by the damaged disc can last for years.

Herniated Disc

As a disc degenerates, the soft inner gel in the disc may leak back into the spinal canal. They are known as disc herniation or herniated disc. Once inside the vertebral canal, the herniated disc material then puts pressure on the nerve, causing pain to radiate down the nerve leading to sciatica or leg pain (from a lumbar herniated disc) and arm pain (from a cervical herniated disc).

What’s a Herniated Disc Pinched Nerve, Bulging Disc?

Many terms could also be used to describe issues with spinal disc and disc pain, and everyone can be used differently and, at times, interchangeably. Some commonly used terms include:

- Herniated disc

- Pinched nerve

- Ruptured/torn disc

- Bulging disc

- Disc protrusion

- Slipped disc

There is no main consensus on the use of these terms, and it will be frustrating to hear one diagnosis described in many different ways. The medical diagnosis recognizes the underlying cause of back pain, leg pain, and other symptoms. It is most convenient to gain a clear understanding of the medical diagnosis than to sort through various medical terms.

Two Causes of Pain: Pinched Nerve vs. Disc Pain

There are two major ways a spinal disc can cause pain:

- Pinched nerve. In a few cases a herniated disc itself is not painful, but rather the material leaking out of the disc pinches, inflames, or irritates a nearby nerve, causing radicular pain. Radicular pain (also called nerve root pain), describes sharp, shooting pains that radiate to other parts of the body, such as from the low back down the leg or from the neck down the arm. Leg pain from a pinched nerve is often called sciatica.

- Disc pain. A spinal disc itself may be the source of pain if it dehydrates or degenerates to the point of causing pain and instability in the spinal segment (called degenerative disc disease). Degenerative disc pain tends to include chronic, low-level pain around the disc and occasional episodes of more severe pain.

A herniated disc or degenerative disc disease typically occurs in the cervical spine (neck) and lumbar spine (lower back). Disc pain tends to be most often in the lower back, where most of the movement and weight-bearing in the spine occurs. These conditions are unusual in the mid-back (the thoracic spine).

Cervical Discs

cervical discs that support the neck’s vertebral bones while also enabling flexibility for head movements. Sitting between adjacent cervical vertebrae stacked atop one another, each cervical disc acts as a shock absorber to help the cervical spine handle various stresses and loads. There are six intervertebral discs within the highly mobile cervical spine. These cervical discs tend to be thinner than the lumbar discs within the lower back but thicker than the thoracic discs within the less mobile upper back.

Anatomy – Each cervical disc has 2 basic components:

- Outer layer. This tough exterior, known as the annulus fibrosus, is comprised of collagen fibers that surround and protect the inner core. The annulus fibrosus also allocates the forces placed on the structure.

- Inner core. This soft jelly interior, called the nucleus pulposus, maybe a loose, fibrous network suspended in mucoprotein gel that is sealed by the annulus fibrosus. The nucleus pulposus helps to supply cushioning and flexibility to the disc.

The discs have to be well hydrated in order to maintain the strength and softness to serve as the spine’s major carrier of axial load. With age, the cervical discs lose water, stiffen, or become less flexible in adjusting to compression. Such degenerative changes may end in a herniated cervical disc, which is when the disc’s inner core extrudes through its outer layer and comes in touch with the nerve root and/or spinal nerve. In other instances, the cervical disc can degenerate as a result of direct trauma or gradual changes. With no blood supply and extremely few nerve endings, a cervical disc cannot repair itself.

Symptoms worsen with specific head positions or activities. A herniated disc’s pain tends to flare up and feel worse during activities, such as while playing a sport or lifting a heavy weight. Certain head positions such as twisting to one side and tilting the head forward may also worsen the pain. Neck stiffness. Pain and inflammation from a cervical herniated disc may restrict certain neck movements and reduce the range of motion. The specific pain patterns and neurological deficits are widely determined by the location of the herniated disc.

Cervical Herniated Disc Signs or Symptoms by Nerve Root

- The cervical spine contains seven vertebrae stacked atop one another, labeled C1 right down to C7. The intervertebral discs are positioned between adjacent vertebral bodies. as an example, the C5 and C6 disc sits between the C5 and C6 vertebrae. If the C5 and C6 disc herniates, it may compress a C6 nerve root. The signs and symptoms caused by a cervical ruptured intervertebral disc may vary depending on which nerve root is compressed. For example:

- C4-C5 (C5 nerve root): Pain, tingling, and numbness may radiate into the shoulder. Weakness could also be felt in the shoulder (deltoid muscle) and other muscles.

- C5 and C6 (C6 nerve root): Pain, tingling, and numbness may be felt in the thumb side of the hand. Weakness could also be experienced in the biceps (muscles in the front of the upper arms) and wrist extensor muscles in the forearms. The C5 and C6 disc is one of the most common herniates.

- C6 and C7 (C7 nerve root): Pain, tingling, and numbness may radiate into the hand and middle finger. Weakness can also be felt in the triceps (muscles in the back of the upper arm), finger extensors, and other muscles. The C6 and C7 disc is commonly considered the most likely to herniate in the cervical spine.

- C7 and T1 (C8 nerve root): Pain, tingling, and numbness may be felt in the outer forearm and pinky side of the hand. Weakness might also be experienced in finger flexors (handgrip) and other muscles.

- These are typical pain patterns associated with cervical disc herniation, but they are not absolute. a few people are simply wired differently than others, and therefore their arm pain and other symptoms will be different.

Cervical Herniated Disc Causes and Diagnosis

Getting an accurate diagnosis for a cervical ruptured intervertebral disc may help to understand the underlying pain mechanisms involved, such as which nerve root might be compressed. An accurate diagnosis also plays a major role in getting the most effective treatment.

Common causes of a cervical herniated disc include:

- Disc degeneration over time. As a disc age, it naturally loses hydration and becomes less flexible and/or durable. Cracks or tears are mostly like to develop in a disc that has a lower water content.

- Trauma. A direct impact on the spine may cause a disc to tear or herniate.

- Other less usual causes of herniated discs are possible, such as connective tissue disorders or other abnormalities in the spine.

Cervical Herniated Disc Diagnosis

Getting an accurate diagnosis for a cervical ruptured intervertebral disc typically involves a three-step process:

- Patient history. The patient’s medical history is reviewed, consisting of any chronic conditions, past injuries, or history of back or neck pain. Information regarding the current symptoms is also gathered.

- Physical examination. The neck may be palpated (felt) for any areas of swelling, tenderness, and pain. The doctor also checks the neck’s range of motion, as well as for any signs of neurological deficits in the arms, such as issues with reflexes, numbness, and weakness.

- Imaging study. An imaging study may show whether a disc has started to flatten out or move beyond its normal location. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan is the preferred method for viewing a ruptured intervertebral disc due to its high-quality view of soft tissues. If magnetic resonance imaging is not an option, a CT or CT myelogram may also be considered.

- In a few cases, enough information may be collected during the patient history and physical examination to begin treatment, so an imaging study is not always requested right away. However, diagnosing a cervical ruptured intervertebral disc as the cause of pain generally requires comparing the patient history, physical exam, imaging study, and an x-ray-guided contrast-enhanced diagnostic injection.

Conservative Treatment for a Cervical Herniated Disc

Pain from a cervical herniated disc can commonly be managed with nonsurgical treatments. Initial treatments can comprise a short period of rest, pain medications, and physical therapy to improve the neck’s strength, flexibility, and posture.

Activity Modification

A cervical herniated disc is typically more painful when it first develops or during intermittent flare-ups, such as during activity. If the neck pain is severe or radiates down into the arm or hand, a short period of rest or activity modification is advised. Some examples may include:

- Refraining from strenuous activities, such as physical labor or playing sports

- Avoiding specific movements that worsen pain, such as turning the head to one side

- Modifying sleep positions, such as by changing the pillow or by sleeping on the back instead of the side or stomach

- Rest tends to assist a cervical herniated disc to become less painful. As the pain decreases, the activity levels may be increased again.

Medications

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) help to decrease inflammation in the body. a number of the worst pain caused by a ruptured intervertebral disc comes from inflammation of nerve roots and other tissues. Over-the-counter NSAIDs (Advil, Aleve, Motrin) are commonly the primary medications recommended. If over-the-counter medications do not provide enough pain relief, a doctor can prescribe another pain reliever on a short-term basis. A Few examples consist of prescription-strength NSAIDs, muscle relaxants, or oral steroids. Due to a higher fear of dangerous side effects, prescription pain medications tend to only be used on a short-term basis, such as during particularly bad flare-ups or for a week or two.

Physical Therapy

Strengthening and stretching the neck can help it to become more immune to pain. Some exercises, such as chin tucks, can also assist the head and neck to maintain better posture. Weakened neck muscles are more likely to guide to forward head posture and neck pain. When the head is instead held in neutral alignment with the ears directly above the shoulders, lower stress is placed on the cervical spine and its discs. A physical therapist and another health professional may design a physical therapy program to meet the patient’s specific needs. For example, a few exercises or stretches can need to be modified to reduce pain or target certain muscles. In time, most of the patients are able to continue neck exercises and stretch at home to maintain neck strength and flexibility over the long term.

Injections

If oral medications and physiotherapy do not provide enough pain relief for a cervical herniated disc, therapeutic injections could also be considered. Most injections for neck pain are performed using fluoroscopy (x-ray guidance) or contrast dye to visualize the needle’s exact placement in the spine. The goal of injection for a cervical ruptured intervertebral disc is to place the medication directly where it needs to be without damaging any critical structures in the spine, such as nerve roots, blood vessels, or the spinal cord. Two often injections for cervical herniated discs include:

- Cervical epidural steroid injection. A steroid solution is injected into the epidural space (outer layer of the spinal canal) to scale back inflammation. This injection is by far and away the most common one used for herniated discs.

- Selective nerve root injection. A steroid solution and anesthetic are injected near the nervus spinalis as it exits through the intervertebral foramen. This injection is additionally used to help diagnose which nerve root might be causing pain.

- Many individuals have reported experiencing at least some pain relief from injections for a cervical herniated disc. Rare but serious complications are possible, so it is suggested to check with a doctor about potential benefits and risks.

Other Nonsurgical Treatments

Many other treatments can provide some relief from a cervical herniated disc, such as:

- Ice therapy and heat therapy. Applying ice for 15 or 20 minutes at a time may assist to reduce inflammation and alleviating pain. Some individuals may find applying heat for 15 to 20 minutes at a time also offers relief. Whether applying ice or heat, allow 2 hours between applications to decrease the risk of skin damage.

- Cervical traction. A mechanical device is strapped to the head or used to gently lift upward and stretch the cervical spine. The goal is to decrease the pressure on the discs and nerve roots. a few people experience pain relief during traction but others do not. If traction provides relief, some patients may have an option for a home device to perform the treatment on their own.

- Massage therapy. A gentle massage can provide some relief by helping to loosen muscles, which increases blood flow and promote relaxation. If a massage worsens pain, then stop immediately.

Other treatments for cervical herniated disc pain are also available and may provide relief for some individuals, including transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) therapy, acupuncture, mindful meditation, and others. a few trials and errors may be needed before finding the combination of treatments that provides the most relief. If neurological deficits continue to worsen, such as increasing arm numbness and weakness, surgery may be considered.

Thoracic Discs

There are 24 intervertebral discs in the spine. Of those, 12 are situated in the thoracic spine. Every thoracic disc sits between two vertebrae to produce cushioning and shock absorption while preventing the vertebrae from grinding against each other. Thoracic discs tend to be thinner than cervical discs and lumbar discs, which can contribute to the thoracic spine’s relative lack of mobility compared to the neck and lower back. another distinguishing feature of the thoracic discs is that each one but the bottom two interfaces with the ribs. Thoracic Disc Construction – Each thoracic disc consists of the following: Outer layer (annulus fibrosis).

This durable exterior of the disc is comprised of tough collagen fibers to assist distribute major loads placed on the spine and protect the disc’s soft interior. The inner core (nucleus pulposus). The jelly like the interior is a loose network of fibers floating in a mucoprotein gel. The disc’s inner core produces more cushioning and movement between adjacent vertebrae than the outer layer. The Intervertebral discs are the most important structures in the human body that do not have blood vessels. A super-thin structure between the disc and vertebra, called a vertebral end plate, provides diffusion in order to nutrients can get into the disc.

How Thoracic Disc Can Contribute to Pain

All intervertebral discs start to lose some hydration as they age or they become less flexible. The process of discs drying out and weakening over time is known as degenerative disc disease, but it is commonly not diagnosed unless pain or other significant symptoms are present. It is frequent for degenerative disc disease to progress in conjunction with osteoarthritis. If degeneration or an injury causes the disc’s outer layer to start developing larger enough tears, it is possible for a ruptured disc to occur, in which the inner layer leaks outside the disc. In some cases, a herniated disc can inflame a nearby structure, causing pain and stiffness.

If a nearby thoracic nerve root becomes inflamed, thoracic radiculopathy may occur with the symptoms of pain, tingling, numbness, or weakness radiating into the chest or abdomen. If the spinal cord becomes inflamed, thoracic myelopathy can occur, which may cause pain, tingling, numbness, and weakness anywhere at that level of the spinal cord or below, as well as the possibility of paralysis and the loss of bodily functions, such as bladder or bowel control. It is also possible for the disc itself to become painful, such as if a nerve grows deeper into the disc or comes in contact with inflammatory proteins, or if a disc tear involves a sensitive nerve.

Thoracic Disc Pain is Less Common

Current medical literature indicates that disc degeneration can occur in the thoracic spine about as commonly as in the more mobile cervical and lumbar spines. although, the degenerative disc disease in the thoracic spine is much less likely to cause pain or any other symptoms. One possibility for this discrepancy may be due to the intervertebral foramen being much larger in the thoracic spine.

While a cervical nerve root takes up about half of the intervertebral foramen or a lumbar nerve root takes up about a third, a thoracic nerve root only takes up about one-twelfth of the foramen, allowing much more room for the spinal nerves and thus decreasing the chance that they become pinched or inflamed.

Thoracic Herniated Disc Causes

When the inner core of any disc between the twelve vertebrae of the thoracic spine extrudes through the outer core and irritates a nearby spinal nerve root, a herniated disc occurs. Determining the causation of the thoracic herniated disc is essential before treatment of upper back pain and/or any related symptoms can take place.

Doctors generally classify thoracic herniated discs as being caused by either one of two sources: Degenerative disc disease, Many thoracic herniated discs occur from gradual wear and tear on the disc, which can lead to settling of the vertebral bodies and calcification about the disc space. Trauma to the upper back, Traumatic herniated discs are defined as those associated with a significant traumatic event that caused the abrupt onset of symptoms.

Thoracic Herniated Discs from Degenerative Disc Disease

When symptomatic of degenerative disc disease, the symptoms of a thoracic herniated disk most often occur between the 4th and 6th decades of life and usually develop very gradually. With degenerative disc disease, the patient’s thoracic back pain and other symptoms are frequently present for a longer period of time before consultation with a physician.

Thoracic Herniated Discs from Sudden Trauma

Any injury that causes a higher degree of sudden force on the discs in the upper spine could lead to a thoracic ruptured intervertebral disc. Examples of a traumatic event that can lead to a thoracic herniated disc include a fall or sports injury that places sudden force on the upper back. Thoracic herniated discs tend to occur in younger patients before significant degenerative disc changes. While in most cases few history of mild trauma has led to an exacerbation of the patient’s symptoms, a mild trauma (such as reaching up while twisting) will usually just worsen symptoms from a degenerated disc. Regardless of the cause of the thoracic back pain, getting a correct diagnosis is critical because it will suggest the treatment of the thoracic herniated disc.

Thoracic Disc Herniation Symptoms

Pain is the most often symptom of a thoracic herniated disc and it may be isolated to the upper back or radiate in a dermatomal (single nerve root) pattern. Thoracic back pain can be exacerbated when coughing or sneezing. Radiating pain can be perceived to be in the chest or belly, and this may lead to a quite different diagnosis that will need to include an assessment of heart, lung, gastrointestinal disorders, kidney, as well as other non-spine musculoskeletal causes.

Within the spine itself there are also many other disorders that may have similar presenting symptoms of upper back pain and radiating pain, such as a spine fracture (e.g. from osteoporosis), infection, certain metabolic disorders, and tumors. If the disc herniates into the spinal cord area, the thoracic herniated disk can also present with myelopathy (spinal cord dysfunction). This may be evident by sensory disturbances (such as numbness) below the level of compression, difficulty with balance and walking, lower extremity weakness, or bowel and bladder dysfunction.

Common Thoracic Herniated Disc Symptoms

Presenting symptoms of a thoracic herniated disc frequently correlate with the size and location of the disc herniation. The herniated material may protrude in a central, lateral (sideways), or Centro-lateral direction with the majority of cases having a central component. Typical symptoms for each comprise:

- Central disc protrusion. This type of herniation typically causes upper back pain and myelopathy, depending on the size of the herniated disc and the amount of pressure on the spinal cord. There is limited room surrounding the spinal cord in the thoracic spine, so a thoracic herniated disc can put pressure on the cord and affect the related nerve function. In serious cases, a thoracic herniated disc may lead to paralysis from the waist down.

- Lateral disc herniation. When herniating laterally, or to the side, the thoracic herniated disc is most likely to impinge on the exiting nerve root at that level of the spine and cause radiating chest wall or abdominal pain.

- Centro-lateral disc herniation. This type of thoracic herniated disk can present with any combination of symptoms of upper back pain, radiating pain, or myelopathy.

Thoracic Herniated Disc Diagnosis

The first step in diagnosing a thoracic herniated disc always consists of a good patient medical history and physical examination. The spine physician will begin by getting a better understanding of the patient’s symptoms, which comprises the:

- Location of the pain

- The severity of the pain

- Type of pain (numbness, weakness, burning, etc.).

- The physician will often follow up by learning if any injuries occurred before the thoracic back pain or if any other problems (weight loss, fevers, illnesses, difficulty urinating) were recently present before the upper back pain. Then the physician will perform a physical examination.

- This combination of the patient’s description of how the pain feels, where it happens, when it occurs, etc., as well as the spine physician’s physical examination, should yield clues to help localize the lesion to the thoracic spine.

Thoracic Disc Herniation Treatment

- The vast majority of thoracic herniated disc symptoms may be treated without thoracic surgery. There are a variety of non-surgical treatment options that can be tried, and common patients will need to try several, or a combination of different treatments, to find what works best for them. Non-Surgical Treatments for Thoracic Herniated Discs

- Non-surgical treatment options for symptoms of a thoracic herniated disc will generally include one or a combination of the following:

- A short period of rest (e.g. one or two days) and activity modification (eliminating the activities or the positions that worsen or cause the thoracic back pain). After a short period of rest, the patient should return to activity as tolerated. Gentle exercise, such as walking, is a good way to return to the activity. Narcotic and non-narcotic analgesic medications help reduce thoracic back pain. Narcotic pain medication is normally only prescribed to treat severe upper back pain for a short period of time. For mild and moderate thoracic back pain, an over-the-counter pain reliever such as acetaminophen (e.g. Tylenol) is often recommended for thoracic herniated discs. Anti-inflammatory agents, help reduce inflammation around the herniated disc in the upper back, including Medications (NSAIDs – such as ibuprofen or a COX-2 inhibitor, or oral steroids).

- Anti-inflammatory injections (such as an epidural steroid injection)

- Ice packs (applied to the painful area for 15 to 20 minutes at a time, as often as necessary)

- Manual manipulation (generally performed by a chiropractor or an osteopathic doctor)

- Strengthening exercises (such as core stabilization exercises)

The patient’s activity levels must be progressed gradually over a 6 to 12-week period as symptoms improve. In the huge majority of cases, the natural history of thoracic disc herniation is one of improvement with one or a combination of the above conservative (non-operative) treatments.

Lumbar Herniated Disc

Spinal discs play a crucial role in the lower back, serving as shock absorbers between the vertebrae, supporting the upper body, or allowing a wide range of movement in all directions. If a disc herniates and leaks some of its inner material, though, the disc may quickly go from easing daily life to aggravating a nerve, triggering back pain and possibly pain and nerve symptoms down the leg. Disc herniation symptoms generally start for no apparent reason. Or they may occur when a person lifts something heavy and twists the lower back, motions that put added stress on the discs. Lumbar herniated discs are a widespread medical problem, most commonly affecting people aged 35 to 50.

How a Lumbar Disc Herniates

A tough outer ring known as the annulus protects the gel-like interior of every disc, called the nucleus pulposus. Due to aging and general wear and tear, the discs lose a few of the fluid that makes them pliable and spongy. As a result, the discs are more prone to become flattered or harder. This process known as disc degeneration starts fairly early in life and commonly shows up in imaging tests in early adulthood. When pressure or stress is placed on the spine, the disc’s outer ring can bulge, crack, or tear.

If this happens in the lower back (the lumbar spine), the disc protrusion can push against the nearby spinal nerve root. Or the inflammatory material from the inside might irritate the nerve. The result is shooting pains in the buttock and down the leg. A person with a herniated disc can be told by the doctor that degenerative disc disease led to the lumbar herniated disc. This term can be alarming and misleading. Degenerative disc disease is not a progressive disease, and it does not always cause chronic or persistent problems.

Lumbar Herniated Disc Symptoms

Symptoms of a lumbar herniated disc vary widely from moderate pain in the back or buttock to widespread numbness and weakness requiring immediate medical care. In the huge majority of cases, the pain eases within six weeks. But despite it is short duration, the pain can be excruciating and make it difficult to participate in everyday activities and responsibilities. For a few, the pain may become chronic and/or debilitating.

While a lumbar herniated disc may be extremely painful, for most people the symptoms are not long-lasting. About 90 % you look after the population who experience a lumbar herniated disc will have no symptoms six weeks later, even if they have had no medical treatment. Experts believe that the symptoms from a lumbar herniated disc can resolve themselves for three reasons:

The body attacks the herniation as a foreign material, shrinking the size of the herniated material and decreasing the number of inflammatory proteins near the nerve root. Over time, few of the water from inside the disc is absorbed into the body, causing the disc to shrink. The small disc is less likely to extend into nerve roots, causing irritation.

Lumbar extension exercises can move the herniated area far away from the spinal discs. Whether exercise may accomplish this is a matter of debate in the medical community. in general, it is thought that the symptoms get better because the smaller size of the herniated material reduces the likelihood it will irritate the nerve root. however a lumbar herniated disc usually triggers attention when it becomes painful, medical research has found it is often for people to have a lumbar disc herniation in their lumbar spine, but no associated pain or another symptom. It is for this propose that care should be taken in the diagnosis to be sure a herniated lumbar disc is causing the problem.

These are some general characteristics of lumbar ruptured intervertebral disc pain:

- Leg pain. The leg pain is usually worse than low back pain. If the pain radiates along with the path of the large sciatic nerve in the back of the leg, it is referred to as sciatica or radiculopathy. Nerve pain. the foremost noticeable symptoms are usually described as nerve pain in the leg, with the pain being described as searing, sharp, electric, radiating, or piercing.

- Variable location of symptoms. looking at variables such as where the disc herniates and the degree of herniation, symptoms may be experienced in the low back, buttock, front or back of the thigh, the calf, foot, and/or toes, and typically affects only one side of the body.

- Neurological symptoms. Numbness, a pins-and-needles feeling, weakness, and/or tingling may be experienced in the leg, foot, and/or toes.

- Foot drop. Neurological symptoms caused by the herniation may include difficulty lifting the foot when walking or standing on the ball of the foot, a condition referred to as foot drop.

- Lower back pain. This sort of pain may be described as dull or throbbing and may be accompanied by stiffness. If the herniated disc causes lower back muscle spasms, the pain may be alleviated somewhat by a day or two of relative rest, applying ice or heat, sitting in a supported recliner, and lying flat on the back with a pillow under the knees.

- Pain that worsens with movement. Pain can follow prolonged standing or sitting, or after walking even a short distance. A laugh, sneeze, or other sudden action can also intensify the pain.

- Pain that worsens from hunching forward. Many find that positions such as slouching or hunching forward in a chair and bending forward at the waist, make the leg pain markedly worse.

- Quick onset. Lumbar herniated disc pain usually develops quickly, although there could also be no identifiable action or event that triggered the pain.

Lumbar ruptured intervertebral disc symptoms are usually more severe if the herniation is extensive. Pain is often milder and limited to the low back if the disc herniation does not affect a nerve. In a few cases, low back pain or leg pain that occurs for a few days and then goes away is the first indication of a herniated disc.

Other Terms which is used for Herniated Disc are Slipped Disc, Ruptured Disc

A ruptured intervertebral disc can be referred to by many names, such as a slipped disc, or a ruptured or bulging disc. The term herniated disc can confuse since spinal discs are firmly attached to the vertebrae and do not slip or move rather, it is just the gel-like inner material of the disc which slips out of the inside. another frequent term for a herniated disc is a pinched nerve. This term describes the effect the ruptured disc material has on a nearby nerve as it compresses or “pinches” that nerve.

A lumbar herniated disc can also be described in reference to its main symptoms, such as sciatica, which is caused by the leaked disc material affecting the larger sciatic nerve. When a nerve root in the lower back that runs into the large sciatic nerve is irritated, pain and/or symptoms can radiate along with the path of the sciatic nerve: down the back of the leg, and within the foot and toes. Sciatica might also be referred to by its main medical term, radiculopathy.

Lumbar Herniated Disc: Causes and Risk Factors

Pain caused by a lumbar ruptured intervertebral disc can seem to occur suddenly, but it is generally the result of a gradual process. The spinal discs in children have a high water content, which assists the discs to stay flexible as they act as cushions between the vertebrae. Over time as a part of the normal aging process, the discs begin to dry out. This leaves the disc’s tough outer ring more brittle and susceptible to cracking and tearing from relatively mild movements, such as picking up a bag of groceries, twisting the lower back while swinging a golf club, or just turning to get in the car. A less common explanation for lumbar herniated discs is a traumatic injury, such as a fall or car accident. An injury can put such a lot of pressure on a disc in the lower back that it herniates.

Factors that will add to the risk of developing a lumbar herniated disc include:

- Age. The most frequent risk factor is between the ages of 35 and 50. The condition rarely causes infrequently after age 80.

- Gender. Men have roughly twice the danger for lumbar herniated discs compared with women.

- Physically demanding work. Jobs that need heavy lifting and other physical labor have been linked to a higher risk of developing a lumbar herniated disc. Pulling, pushing, and twisting actions can add to danger if they are done repeatedly.

- Obesity. Excess weight makes yet another likely to experience a lumbar herniated disc and 12 times more likely to have a similar disc herniate again, called a recurrent disc herniation, after a microdiscectomy surgery. Experts believe that carrying extra weight increases the stress on the lumbar spine, making the individual who is obese more prone to herniation.

- Smoking. Nicotine limits blood flow to spinal discs, which accelerates disc degeneration and hampers healing. A degenerated disc is a smaller amount pliable, making it more likely to tear or crack, which can lead to a herniation. The medical literature is mixed on whether people who smoke are at greater risk for a new herniation following a discectomy.

- Family history. The medical literature has shown a hereditary tendency for disc degeneration, and disc degeneration is related to an increased risk for herniation. One extensive study found that a case history of lumbar herniated discs is the best predictor of a future herniation.

While the above factors all contribute to a better risk of developing a symptomatic lumbar disc herniation, it is possible for anyone of any age to have a herniated disc. A disc also can herniate and become symptomatic for no known reason.

Treatment for a Lumbar Herniated Disc

Treatment Options for a Herniated Disc – The primary goal of treatment for every patient is to help relieve pain and other symptoms resulting from the herniated disc. To achieve this goal, each patient’s treatment plan should be individualized based on the source of the pain, the severity of the pain, and the specific symptoms that the patient exhibits. In a general sense, patients usually are advised to start out with a course of conservative care (non-surgical) prior to considering spine surgery for a herniated disc.

Whereas this is frequently true in general, for some patients early surgical intervention is beneficial. as example, when a patient features a progressive major weakness within the arms or legs due to nerve root pinching from a herniated disc, having surgery sooner can stop any neurological progression and make an optimal healing environment for the nerve to recover. In such cases, without surgical intervention, nerve loss can occur and thus the damage may be permanent. There are also a few relatively rare conditions that need immediate surgical intervention. For instance, cauda equina syndrome, which is typically marked by progressive weakness in the legs and sudden bowel or bladder dysfunction, requires prompt medical care and surgery.

Conservative and Surgical Treatments

For lumbar and cervical herniated discs, conservative (non-surgical) treatments can normally be applied for around four to six weeks to help reduce pain and discomfort. A process of trial and error is usually necessary to find the right combination of treatments. Patients may try one treatment at a time or may find it helpful to use a mixture of treatment options at once. For instance, treatments focused on pain relief (such as medications) may help patients better tolerate other treatments (such as manipulation or physical therapy). additionally, to help with recovery, physical therapy is commonly used to educate patients on good body mechanics (such as proper lifting technique) which helps to prevent excessive wear and tear on the discs. If conservative treatments are successful in reducing pain and discomfort, the patient may prefer to continue with them. For those patients who experience severe pain and a high loss of function and don’t find relief from conservative treatments, surgery could also be considered as an option.

Most cases of lumbar herniated disc symptoms resolve on their own within six weeks, so patients are frequently advised to start with non-surgical treatments. although, this can vary with the nature and severity of the symptoms. Initial pain control options are likely to consist:

- Ice application. The application of ice or a cold pack may be helpful to ease initial inflammation and muscle spasms associated with a lumbar herniated disc. An ice massage can also be helpful. Ice is the most effective for the first 48 hours after the back pain has started.

- Pain medications. The doctor can recommend non-prescription non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen or naproxen to treat pain and inflammation.

- Muscle relaxants. Muscle spasms may accompany a lumbar ruptured intervertebral disk, and these prescription medications can offer relief from the painful spasms.

- Heat therapy. Applying heat may help relieve painful muscle spasms after the first 48 hours. Heating pads, a hot compress, and/or adhesive heat wraps are all good options. Moist heat, such as a hot bath, could also be preferred.

- Heat and ice. Some people find alternating hot and cold packs provides the utmost pain relief.

- Bed rest for severe pain is best limited to at least one or two days, as extended rest will lead to stiffness and more pain. After that point, light activity and common movement with rest breaks as needed are advised. Heavy lifting and strenuous exercise must be avoided.

Additional Therapies for Lumbar Herniated Disc

These other therapies are frequently helpful for longer-term pain relief: Physical therapy is important in teaching targeted stretching or exercises for rehabilitation. The program can also teach the patient safer ways to perform ordinary activities, such as lifting and walking. Epidural injections of steroid medications may offer pain relief in some cases. An epidural steroid injection is meant to provide enough pain relief for the patient to make progress with rehabilitation. The consequences vary, and pain relief is temporary.

Bulging Disc

A bulging disc may be a condition in which a disc loses its original shape and expands (bulges), which may place pressure on a surrounding nerve root and cause pain. Discs are gel-filled pads that cushion the people’s vertebrae of the spine, acting like shock absorbers and allowing movement and adaptability of the vertebrae. few times spinal discs are likened to a jelly donut with a central softer component (nucleus pulposus). When a disc “bulges,” an element of its tough outer wall can protrude into the spinal canal and press on a nerve, which causes pain. Looking at which nerve is pressed by the disc, the pain can appear during a leg, arm, or elsewhere.

Causes of a Bulging Disc

The Spinal discs absorb the wear and tear that is placed on the spine. Over time, the discs start to degenerate or weaken. The foremost often situated for a bulging disc is between the fourth and fifth lumbar vertebrae in the low back. This area continually absorbs the impact of bearing the load of the upper body. The lower back is additionally critically involved in the body’s movements throughout the day, such as the twisting of the torso (rotating side to side), bending, and lifting.

Degenerative disc disease is that the most common cause of a bulging disc which may result in spinal osteoarthritis. Other factors which will cause or contribute to bulging discs include Strain or injury.

- Obesity.

- Smoking.

- Poor posture.

- Inactivity.

What are the Symptoms of a Bulging Disc?

A bulging disc can have no signs or symptoms (asymptomatic). In fact, about half of the people with bulging discs never experience any symptoms or pain. a few patients only learn they have a bulging disc after imaging tests for another medical issue. although, most people immediately feel pain if a bulging disc presses on a nerve. Pain from a bulging disc can begin as a spasm in the back or neck that limits movement. If the bulging disc compresses a nerve, pain can develop in the leg or arm. Some of the more often bulging disc symptoms include:

- Pain or tingling within the neck, shoulders, arms, hands or even fingers can result from a bulging disc in the cervical (upper spine) area.

- Pain within the upper back that radiates to the chest or stomach can signal a thoracic (mid-spine) bulging disc. It is important to determine the root of these symptoms since they may also be a sign of heart, lung, or gastrointestinal problems.

- Muscle spasms and/or lower back pain might indicate a bulging disc in the lumbar (lower back) region. The lower back holds most of the upper body’s weight, which is why approximately 90% of all bulging discs occur within the lumbar spine. Sometimes, the bulging disc will place pressure on the sciatic nerve, causing sciatica that has pain radiating down one leg.

How is a Bulging Disc Diagnosed?

As noted earlier, symptoms of a bulging disc might not appear in the back but in the other parts of the body. A medical diagnosis will identify the actual cause of the pain or other symptoms that can be a result of a bulging disc. A proper diagnosis to determine the cause of pain is through a mixture of three steps:

- Review of medical history.

- A physical exam.

- Diagnostic testing.

- Review of Medical History

Taking the time to get a full medical history is important in ruling out, or identifying, other possible conditions that which will be causing the pain. The history will consist of information about any recurring health problems and previous diagnoses. The doctor will want to understand about any past treatments and surgeries, current medications, case history of illness, and the other health concerns the patient may have. The review will include a patient’s description of the sort of pain, and what triggers the pain.

Physical Exam

Depending on the symptoms, a physical exam may consist of one or more of the following tests:

Nerve function. A reflex test on the legs and arms is used to determine whether the nerves produce a reaction. The test assists to determine if there is nerve root compression in the spine.

Muscle strength. To urge a better understanding of whether there is spinal nerve root compression from a disc, the doctor will likely conduct a neurological exam to assess muscle strength. The doctor will want to work out if there is muscle atrophy, twitching, or any abnormal movements.

Pain with touch or motion. By touching or determining which movements cause pain, a doctor can gain a better idea of where the pain is originating.

Diagnostic Tests

After the doctor has information relating to a patient’s medical history and has completed a physical exam, diagnostic tests can be necessary to confirm the cause. Diagnostic tests assist the doctor to work out the location of a bulging disc and which nerve roots are being compressed. Diagnostic tests may consist:

CT scan. A Computerized Tomography (CT) scan combines X-ray images taken from different angles and uses computer processing to create cross-sectional images that provide more information than plain X-rays.

MRI scan. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) shows the condition of the spinal nerves and anatomy, consisting of disc alignment, height, hydration, and configuration.

While these imaging test outcomes are important, they are only a tool. The test results don’t seem to be as meaningful in determining the cause of pain as the patient’s specific symptoms and the results of the physical exam.

How may be a Bulging Disc Treated?

There is a wide range of non-surgical treatments available for bulging discs, a number of which may work better for some patients than others. Specific treatments depend on the length of your time the patient has experienced symptoms and the severity of the pain. Other considerations include the character of the symptoms (such as weakness or numbness) and the age of the patient. For many, the symptoms of a bulging disc will diminish over time. While there are not any hard or fast guidelines for treating a bulging disc, the first goals of any treatment are twofold: To provide relief of pain, especially leg pain which may be quite severe and debilitating.

To allow the patient to return to a general level of everyday activity.

Conservative therapy frequently begins with medication and physical therapy. In a few cases, restricted activities could also be necessary until the pain subsides. Treatments include:

- Medication. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen are the first-line medications for bulging discs. For more severe pain, prescription medication could also be necessary. during a few cases, a muscle relaxer can assist if there are muscle spasms.

- Physical therapy. A physical therapist can prescribe positions and/or exercises designed to minimize the pain of a bulging disc by relieving pressure on the nerve. Exercise is an essential component of rehabilitation in most of all cases of back pain.

- Chiropractic. Spinal manipulation is typically moderately effective for lower back pain that has lasted for at least a month. This treatment is best for low back pain.

- Massage. This hands-on therapy often provides short-term relief for patients dealing with chronic low back pain.

- Ultrasound therapy. The back is treated with sound waves, which are tiny vibrations that are produced to relax body tissue.

- Heat or cold. Initially, cold packs can assist to relieve pain and inflammation. After a few days, switch to kind heat for relief.

- Limited bed rest. an excessive amount of bed rest can lead to stiff joints and weak muscles, which can complicate recovery. Instead of remaining in bed, rest in a position of comfort for 30 minutes, and then go for a short walk or do some light work, avoiding activities that worsen the pain.

- Braces and support devices. These devices can assist by providing compression and stability to help reduce pain.

- Steroids. Cortisone injections (epidural steroid injections) may provide longer-term relief because the medicine is injected into the area around the spinal nerves. Oral steroids may be helpful in reducing swelling and inflammation.

- Anticonvulsants. Drugs are usually designed to control seizures which may be helpful in treating radiating nerve pain often associated with a bulging disc.

- Spinal decompression therapy. A non-surgical form of intermittent spinal traction can help reduce bulging disc symptoms. Pain relief might last for months at a time.

- Electrotherapy. Treatment commonly includes using a transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulator (TENS). More advanced treatments may consist of percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (PENS), and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS).

- Alternative Medicine.

There are also alternative and complementary treatments that can help ease the pain of a bulging disc, including:

- Acupuncture. however the results are usually only modest, acupuncture appears to ease chronic back and neck pain reasonably well for some patients.

- Yoga. A mixture of physical activity, breathing exercises, and meditation, yoga can often assist to improve function and relieve chronic back pain in some people.

- Reiki. Reiki may be a Japanese treatment that aims to relieve pain by using specific hand placements.

- Moxibustion. This method uses heat-specific parts of the body (which are known as “therapy points”) by using glowing sticks made from mugwort (“Moxa”) or heated needles that are put close to the therapy points.

If non-surgical treatments do not provide pain relief after 12 weeks of use, and/or thus the pain is severe, surgery can be an option. Fortunately, only a few patients with bulging discs need surgery. However, surgery may be necessary if the patient experiences: Severe pain that makes it difficult to maintain a reasonable level of normal activity. Progressive neurological symptoms, such as worsening leg, weakness, and numbness.

- Spinal decompression therapy is a non-surgical form of intermittent spinal traction that can help reduce bulging disc symptoms. the Pain relief might last for months at a time.

- Electrotherapy treatments range from treatments patients could also do at home to surgical procedures. Treatment frequently includes using a transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulator (TENS). More advanced treatments can comprise percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (PENS) and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS).

- Injection medicine therapy consists of epidural steroid injections, non-steroidal injections, trigger point injections, therapeutic injections, nerve blocks, nerve ablations, and joint injections.

Minimally invasive spine surgery has become increasingly popular, offering procedures leading to less pain and faster recovery times. Conditions treated include degenerative disc disease, herniated discs, scoliosis, spinal stenosis, and more.

Conventional open surgery consists of greater risks and does not guarantee success. The surgical options can include lumbar decompression, micro-discectomy (or micro-decompression) to give the nerve root more space to heal, and a lumbar discectomy is a most often outpatient procedure.

How to Avoid a Bulging Disc?

- however, the intervertebral discs begin to show wear and tear with age, there are things you can do to help avoid a bulging disc.

- Maintain healthy body weight. Excess load creates extra stress on the back. By losing weight or maintaining a healthy weight, it is possible to reduce the stress on the lower back.

- Exercise regularly. Keeping core body muscles strong and toned helps to stop the unnecessary stress on the back during normal daily activities.

- Quit smoking. Nicotine may harm the discs in the back because it lowers the ability of the discs to absorb the nutrients necessary to remain healthy. Smoking can also cause the discs to become dry and brittle.

- Use proper lifting techniques. Proper lifting (using the legs) assists to avoid placing excess stress on the back.

- Proper posture. Slumping or slouching alone can not cause back pain. But, after a back strain or injury, bad posture can make the pain worse and increase the time for healing.

- Good standing and walking posture. “Good posture” normally means that your ears, shoulders, and hips are in a straight line, whether standing still or walking.

- Protect your back while sitting. Place a small pillow or rolled towel between the low back and the chair while seated for an extended period.

- Sleeping posture. If possible, keep the back in a neutral position while sleeping. It can help to place a pillow between the knees for side sleepers.

What Is a Disc Protrusion?

Disc protrusion is the mildest form of this condition while a herniated disc, also known as a ruptured disc, is at the other end of the spectrum, he says. “Think of a cloudy day where it could be just a little bit cloudy or very dense and cloudy. The disc protrusion is like a slightly cloudy day and the disc herniation is a very dense cloudy day.” the difference between a disc protrusion and a disc herniation by comparing it to a jelly doughnut.

the disc in your back is sort of a jelly doughnut without any holes in it,” he says. “If a few of the jelly protrudes out of the hole, that is a disc protrusion. But if you squeeze the doughnut or more jelly squirts out of the hole, this is a herniated disc.” That “jelly” is the material inside the disc between every vertebra of your spine which acts as a shock absorber. Once a herniated disc or protruding disc occurs, it generally stays like this, he says. few times the herniation over time becomes calcified or sort of a bone spur, and on rare occasions, it will reabsorb on its own. But we never know if that is going to occur or how long it is going to take.” In either case, when the jelly-like material pushes out of the space between the discs, it may cause pain.

Types of Disc Protrusion

The protrusion is protruding into:

- Central, the disc protrusion is encroaching into the vertebral canal itself, with or without a spinal cord or nerve compression

- Foraminal, the disc is encroaching into the foramen, the space through which nerve roots branch off the medulla spinalis and exit the vertebrae

- Paracentral, the foremost common type, paracentral disc protrusions crowd the space between the central canal and the foramen.

What causes disc protrusion?

A bulging disc may be a common back injury that can occur from several causes. Most of the bulging discs stem from one or more of the following factors.

- Wear and tear. The foremost common cause of disc protrusion is wear and tear over time. As we age, spinal discs become drier, less flexible, compressed, and more susceptible to tears and injuries. The supportive ligaments begin to loosen or weaken, causing the disc to bulge outward as the nucleus material presses against the outer ring. Once the spinal discs start degenerating, even a little movement like bending over, twisting, sneezing, or lifting an object can lead to disc protrusion.

- Repetitive movements. Performing repetitive lifting, twisting, or bending movements, especially if you are employed in a physically demanding job like construction or carpentry, causes discs to wear out over time. because the tough outer ring weakens and becomes less able to absorb shock, the nucleus material presses against the outer ring.

- Traumatic injury. few times, a single injury places too much stress and pressure on the disc and causes it to weaken and bulge. These types of injuries may include using your back muscles to lift a really heavy object, lifting and twisting at the same time, a bad fall, or a high-impact car accident.

Risk factors for developing a bulging disc which consist of age, obesity, smoking, a physically demanding occupation, a sedentary lifestyle, poor posture, and genetics.

How may be a Bulging Disc Treated?

TREATMENT OPTIONS – In some cases, non-surgical treatments are successful in managing pain and symptoms from a bulging disc. A protruding disc can require several weeks or months to heal completely, but early treatment can prevent the disc from rupturing in the future. Conservative treatment options include:

- Rest. attempt to avoid activities that put stress on the spine or aggravate back pain. That’s not to say you should take complete bed rest — staying in bed can lead to increased pain, stiffness, and weakness. Stay active while modifying activities that place plenty of pressure on your back.

- Anti-inflammatory medications. Over-the-counter NSAIDs can assist in relieving mild back and leg pain. If over-the-counter medication is not enough, your doctor might prescribe stronger anti-inflammatories or a cortisone injection.

- Physical therapy. Physical therapy could also help you strengthen the core, low back, and leg muscles that support the spine. Improving your strength and flexibility will assist to prevent future injuries.

While it is rare for a bulging disc need to require surgery, some do. If your condition requires spine surgery, ask to your doctor to see if you qualify for a minimally invasive approach. You may help to prevent spinal disc injuries by maintaining a healthy weight, getting regular exercise, quitting smoking, and practicing good posture and body positioning.

FAQ

What causes L4 and L5 disc problems?

External trauma from falls or motor vehicle accidents can cause facet joint dislocation, fracture, or damage to the cauda equina at this level. Rarely, tumors and infections can affect the L4-L5 vertebrae and spinal segment.

Is it possible to have 4 herniated discs?

Primarily, it is quite common to have multiple herniated discs in the lumbar spine. In studies of person who were not experiencing back pain, many had disc herniations that caused no pain symptoms. Second, the term “disc herniation” is extremely broad and can describe mild bulges to extreme protrusions that cause pain.

Is walking good for L4-L5 disc bulges?

Daily walks are a superb way to exercise with a herniated disc, without putting additional strain on your spine and causing painful symptoms to flare up.

Can back discs be repaired?

After a rupture, a jelly-like material leaks out of a ruptured intervertebral disc, causing inflammation and pain. The injury is typically treated one of two ways: a surgeon sews up the hole, leaving the disc deflated; or the disc is refilled with a replacement material, which does not prevent repeat leakages.

Can you remove a disc from your back?

Diskectomy is a surgery to get a ridge of the damaged part of a disk in the spine that has its soft center pushing out through the tough outer lining. A herniated disk may irritate or press on nearby nerves. Diskectomy works best for treating the pain that travels down the arms and legs from a compressed nerve.