Vitamin B 12

What is a Vitamin B 12?

Vitamin B12 is a water-soluble vitamin that is naturally present in some foods, added to others, and available as a dietary supplement and a prescription medication.

Vitamin B12 exists in several forms and contains the mineral cobalt, so compounds with vitamin B12 activity are collectively called “cobalamins”. Methylcobalamin and 5-deoxyadenosylcobalamin are the forms of vitamin B12 that are active in human metabolism.

Vitamin B12 is required for proper red blood cell formation, neurological function, and DNA synthesis. Vitamin B12 functions as a cofactor for methionine synthase and L-methylmalonyl-CoA mutase.

Methionine synthase catalyzes the conversion of homocysteine to methionine. Methionine is required for the formation of S-adenosylmethionine, a universal methyl donor for almost 100 different substrates, including DNA, RNA, hormones, proteins, and lipids. L-methylmalonyl-CoA mutase converts L-methylmalonyl-CoA to succinyl-CoA in the degradation of propionate, an essential biochemical reaction in fat and protein metabolism. Succinyl-CoA is also required for hemoglobin synthesis.

Vitamin B12, bound to protein in food, is released by the activity of hydrochloric acid and gastric protease in the stomach. When synthetic vitamin B12 is added to fortified foods and dietary supplements, it is already in free form and, thus, does not require this separation step.

Free vitamin B12 then combines with intrinsic factor, a glycoprotein secreted by the stomach’s parietal cells, and the resulting complex undergoes absorption within the distal ileum by receptor-mediated endocytosis.

Approximately 56% of a 1 mcg oral dose of vitamin B12 is absorbed, but absorption decreases drastically when the capacity of intrinsic factor is exceeded (at 1–2 mcg of vitamin B12).

Pernicious anemia is an autoimmune disease that affects the gastric mucosa and results in gastric atrophy. This leads to the destruction of parietal cells, achlorhydria, and failure to produce intrinsic factors, resulting in vitamin B12 malabsorption. If pernicious anemia is left untreated, it causes vitamin B12 deficiency, leading to megaloblastic anemia and neurological disorders, even in the presence of adequate dietary intake of vitamin B12.

Vitamin B12 status is typically assessed via serum or plasma vitamin B12 levels. Values below approximately 170–250 pg/mL (120–180 picomol/L) for adults indicate a vitamin B12 deficiency.

However, evidence suggests that serum vitamin B12 concentrations might not accurately reflect intracellular concentrations [6]. An elevated serum homocysteine level (values >13 micromol/L) might also suggest a vitamin B12 deficiency. However, this indicator has poor specificity because it is influenced by other factors, such as low vitamin B6 or folate levels.

Elevated methylmalonic acid levels (values >0.4 micromol/L) might be a more reliable indicator of vitamin B12 status because they indicate a metabolic change that is highly specific to vitamin B12 deficiency.

Recommended Intakes

Intake recommendations for vitamin B12 and other nutrients are provided in the Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) developed by the Food and Nutrition Board (FNB) at the Institute of Medicine (IOM) of the National Academies (formerly the National Academy of Sciences).

DRI is the general term for a set of reference values used for planning and assessing nutrient intakes of healthy people. These values, which vary by age and gender, include:

Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA): Average daily level of intake sufficient to meet the nutrient requirements of nearly all (97%–98%) healthy individuals; often used to plan nutritionally adequate diets for individuals.

Adequate Intake (AI): Intake at this level is assumed to ensure nutritional adequacy; established when evidence is insufficient to develop an RDA.

Estimated Average Requirement (EAR): Average daily level of intake estimated to meet the requirements of 50% of healthy individuals; usually used to assess the nutrient intakes of groups of people and to plan nutritionally adequate diets for them; can also be used to assess the nutrient intakes of individuals.

Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL): Maximum daily intake unlikely to cause adverse health effects.

Table 1 lists the current RDAs for vitamin B12 in micrograms (mcg). For infants aged 0 to 12 months, the FNB established an AI for vitamin B12 that is equivalent to the mean intake of vitamin B12 in healthy, breastfed infants.

Table 1: Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) for Vitamin B12

Age Male Female Pregnancy Lactation

0–6 months* 0.4 mcg 0.4 mcg

7–12 months* 0.5 mcg 0.5 mcg

1–3 years 0.9 mcg 0.9 mcg

4–8 years 1.2 mcg 1.2 mcg

9–13 years 1.8 mcg 1.8 mcg

14+ years 2.4 mcg 2.4 mcg 2.6 mcg 2.8 mcg

Sources of Vitamin B12

Food

Vitamin B12 is naturally found in animal products, including fish, meat, poultry, eggs, milk, and milk products. Vitamin B12 is generally not present in plant foods, but fortified breakfast cereals are a readily available source of vitamin B12 with high bioavailability for vegetarians. Some nutritional yeast products also contain vitamin B12. Fortified foods vary in formulation, so it is important to read the Nutrition Facts labels on food products to determine the types and amounts of added nutrients they contain.

Several food sources of vitamin B12 are listed in Table 2.

- Table 2: Selected Food Sources of Vitamin B12

- Food Micrograms (mcg)

- per serving Percent DV*

- Clams, cooked, 3 ounces 84.1 1,402

- Liver, beef, cooked, 3 ounces 70.7 1,178

- Nutritional yeasts, fortified with 100% of the DV for vitamin B12, 1 serving 6.0 100

- Trout, rainbow, wild, cooked, 3 ounces 5.4 90

- Salmon, sockeye, cooked, 3 ounces 4.8 80

- Trout, rainbow, farmed, cooked, 3 ounces 3.5 58Tuna fish, light, canned in water, 3 ounces 2.5 42

- Cheeseburger, double patty, and bun, 1 sandwich 2.1 35

- Haddock, cooked, 3 ounces 1.8 30

- Breakfast cereals, fortified with 25% of the DV for vitamin B12, 1 serving 1.5 25

- Beef, top sirloin, broiled, 3 ounces 1.4 23

- Milk, low-fat, 1 cup 1.2 18

- Yogurt, fruit, low-fat, 8 ounces 1.1 18

- Cheese, Swiss, 1 ounce 0.9 15

- Beef taco, 1 soft taco 0.9 15

- Ham, cured, roasted, 3 ounces 0.6 10

- Egg, whole, hard-boiled, 1 large 0.6 10

- Chicken, breast meat, roasted, 3 ounces 0.3 5

- *DV = Daily Value.

Dietary supplements

In dietary supplements, vitamin B12 is usually present as cyanocobalamin, a form that the body readily converts to the active forms methylcobalamin and 5-deoxyadenosylcobalamin. Dietary supplements can also contain methylcobalamin and other forms of vitamin B12.

Existing evidence does not suggest any differences among forms with respect to absorption or bioavailability. However, the body’s ability to absorb vitamin B12 from dietary supplements is largely limited by the capacity of intrinsic factors. For example, only about 10 mcg of a 500 mcg oral supplement is actually absorbed in healthy people.

In addition to oral dietary supplements, vitamin B12 is available in sublingual preparations such as tablets or lozenges. These preparations are frequently marketed as having superior bioavailability, although evidence suggests no difference in efficacy between oral and sublingual forms.

Prescription medications

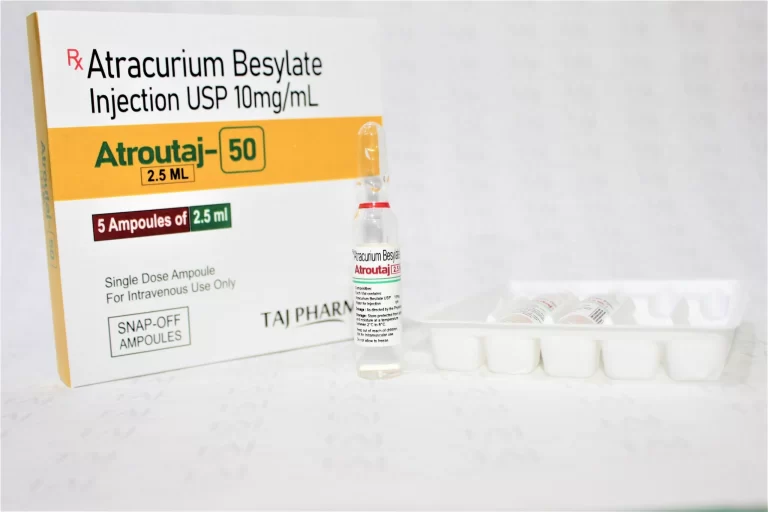

- Vitamin B12, in the form of cyanocobalamin and occasionally hydroxocobalamin, can be administered parenterally as a prescription medication, usually by intramuscular injection.

- Parenteral administration is typically used to treat vitamin B12 deficiency caused by pernicious anemia and other conditions that result in vitamin B12 malabsorption and severe vitamin B12 deficiency.

- Vitamin B12 is also available as a prescription medication in a gel formulation applied intranasally, a product marketed as an alternative to vitamin B12 injections that some patients might prefer.

- This formulation appears to be effective in raising vitamin B12 blood levels, although it has not been thoroughly studied in clinical settings.

Individuals who have trouble absorbing vitamin B12 from foods, as well as vegetarians who consume no animal foods, might benefit from vitamin B12-fortified foods, oral vitamin B12 supplements, or vitamin B12 injections.

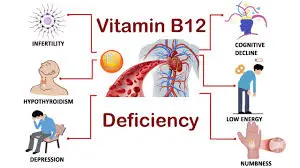

Vitamin B12 Deficiency:

Vitamin B12 deficiency is characterized by megaloblastic anemia, fatigue, weakness, constipation, loss of appetite, and weight loss. Neurological changes, such as numbness and tingling in the hands and feet, can also occur. Additional symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency include difficulty maintaining balance, depression, confusion, dementia, poor memory, and soreness of the mouth or tongue.

The neurological symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency can occur without anemia, so early diagnosis and intervention are important to avoid irreversible damage. During infancy, signs of a vitamin B12 deficiency include failure to thrive, movement disorders, developmental delays, and megaloblastic anemia.

Many of these symptoms are general and can result from a variety of medical conditions other than vitamin B12 deficiency.

Typically, vitamin B12 deficiency is treated with vitamin B12 injections, since this method bypasses potential barriers to absorption. However, high doses of oral vitamin B12 may also be effective.

The authors of a review of randomized controlled trials comparing oral with intramuscular vitamin B12 concluded that 2,000 mcg of oral vitamin B12 daily, followed by a decreased daily dose of 1,000 mcg and then 1,000 mcg weekly and finally, monthly might be as effective as intramuscular administration.

Overall, an individual patient’s ability to absorb vitamin B12 is the most important factor in determining whether vitamin B12 should be administered orally or via injection. In most countries, the practice of using intramuscular vitamin B12 to treat vitamin B12 deficiency has remained unchanged.

Folic acid and vitamin B12

- Large amounts of folic acid can mask the damaging effects of vitamin B12 deficiency by correcting the megaloblastic anemia caused by vitamin B12 deficiency without correcting the neurological damage that also occurs.

- Moreover, preliminary evidence suggests that high serum folate levels might not only mask a vitamin B12 deficiency but could also exacerbate the anemia and worsen the cognitive symptoms associated with vitamin B12 deficiency.

- Permanent nerve damage can occur if vitamin B12 deficiency is not treated. For these reasons, folic acid intake from fortified food and supplements should not exceed 1,000 mcg daily in healthy adults.

Groups at Risk of Vitamin B12 Deficiency

The main causes of vitamin B12 deficiency include vitamin B12 malabsorption from food, pernicious anemia, postsurgical malabsorption, and dietary deficiency. However, in many cases, the cause of vitamin B12 deficiency is unknown. The following groups are among those most likely to be vitamin B12 deficient.

Older adults

- Atrophic gastritis, a condition affecting 10%–30% of older adults, decreases the secretion of hydrochloric acid in the stomach, resulting in decreased absorption of vitamin B12.

- Decreased hydrochloric acid levels might also increase the growth of normal intestinal bacteria that use vitamin B12, further reducing the amount of vitamin B12 available to the body.

- Individuals with atrophic gastritis are unable to absorb the vitamin B12 that is naturally present in food. Most, however, can absorb the synthetic vitamin B12 added to fortified foods and dietary supplements.

- As a result, the IOM recommends that adults older than 50 years obtain most of their vitamin B12 from vitamin supplements or fortified foods. However, some elderly patients with atrophic gastritis require doses much higher than the RDA to avoid subclinical deficiency.

- Individuals with pernicious anemia

- Pernicious anemia, a condition that affects 1%–2% of older adults, is characterized by a lack of intrinsic factors. Individuals with pernicious anemia cannot properly absorb vitamin B12 in the gastrointestinal tract. Pernicious anemia is usually treated with intramuscular vitamin B12. However, approximately 1% of oral vitamin B12 can be absorbed passively in the absence of intrinsic factors, suggesting that high oral doses of vitamin B12 might also be an effective treatment.

- Individuals with gastrointestinal disorders

- Individuals with stomach and small intestine disorders, such as celiac disease and Crohn’s disease, may be unable to absorb enough vitamin B12 from food to maintain healthy body stores.

- Subtly reduced cognitive function resulting from early vitamin B12 deficiency might be the only initial symptom of these intestinal disorders, followed by megaloblastic anemia and dementia.

- Individuals who have had gastrointestinal surgery

- Surgical procedures in the gastrointestinal tract, such as weight loss surgery or surgery to remove all or part of the stomach, often result in a loss of cells that secrete hydrochloric acid and intrinsic factor. This reduces the amount of vitamin B12, particularly food-bound vitamin B12, that the body releases and absorbs.

- Surgical removal of the distal ileum also can result in the inability to absorb vitamin B12. Individuals undergoing these surgical procedures should be monitored preoperatively and postoperatively for several nutrient deficiencies, including vitamin B12 deficiency.

Vegetarians:

- Strict vegetarians and vegans are at greater risk than lacto-ovo vegetarians and nonvegetarians of developing vitamin B12 deficiency because natural food sources of vitamin B12 are limited to animal foods.

- Fortified breakfast cereals and fortified nutritional yeasts are some of the only sources of vitamin B12 from plants and can be used as dietary sources of vitamin B12 for strict vegetarians and vegans.

- Fortified foods vary in formulation, so it is important to read the Nutrition Facts labels on food products to determine the types and amounts of added nutrients they contain.

- Pregnant and lactating women who follow strict vegetarian diets and their infants

- Vitamin B12 crosses the placenta during pregnancy and is present in breast milk. Exclusively breastfed infants of women who consume no animal products may have very limited reserves of vitamin B12 and can develop vitamin B12 deficiency within months of birth .

- Undetected and untreated vitamin B12 deficiency in infants can result in severe and permanent neurological damage.

- The American Dietetic Association recommends supplemental vitamin B12 for vegans and lacto-ovo vegetarians during both pregnancy and lactation to ensure that enough vitamin B12 is transferred to the fetus and infant.

- Pregnant and lactating women who follow strict vegetarian or vegan diets should consult with a pediatrician regarding vitamin B12 supplements for their infants and children.

Vitamin B12 and Health

Cardiovascular disease

- Cardiovascular disease is the most common cause of death in industrialized countries, such as the United States, and is on the rise in developing countries. Risk factors for cardiovascular disease include elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels, high blood pressure, low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels, obesity, and diabetes.

- Elevated homocysteine levels have also been identified as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Homocysteine is a sulfur-containing amino acid derived from methionine that is normally present in the blood. Elevated homocysteine levels are thought to promote thrombogenesis, impair endothelial vasomotor function, promote lipid peroxidation, and induce vascular smooth muscle proliferation . Evidence from retrospective, cross-sectional, and prospective studies links elevated homocysteine levels with coronary heart disease and stroke.

- Vitamin B12, folate, and vitamin B6 are involved in homocysteine metabolism. In the presence of insufficient vitamin B12, homocysteine levels can rise due to inadequate function of methionine synthasis. Results from several randomized controlled trials indicate that combinations of vitamin B12 and folic acid supplements with or without vitamin B6 decrease homocysteine levels in people with vascular disease or diabetes and in young adult women.

- In another study, older men and women who took a multivitamin/multimineral supplement for 8 weeks experienced a significant decrease in homocysteine levels .

- Evidence supports the role of folic acid and vitamin B12 supplements in lowering homocysteine levels, but results from several large prospective studies have not shown that these supplements decrease the risk of cardiovascular disease.

- In the Women’s Antioxidant and Folic Acid Cardiovascular Study, women at high risk of cardiovascular disease who took daily supplements containing 1 mg vitamin B12, 2.5 mg folic acid, and 50 mg vitamin B6 for 7.3 years did not have a reduced risk of major cardiovascular events, despite lowered homocysteine levels.

- The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation (HOPE) 2 trial, which included 5,522 patients older than 54 years with vascular disease or diabetes, found that daily treatment with 2.5 mg folic acid, 50 mg vitamin B6, and 1 mg vitamin B12 for an average of 5 years reduced homocysteine levels and the risk of stroke but did not reduce the risk of major cardiovascular events.

- In the Western Norway B Vitamin Intervention Trial, which included 3,096 patients undergoing coronary angiography, daily supplements of 0.4 mg vitamin B12 and 0.8 mg folic acid with or without 40 mg vitamin B6 for 1 year reduced homocysteine levels by 30% but did not affect total mortality or the risk of major cardiovascular events during 38 months of follow-up.

- The American Heart Association has concluded that the available evidence is inadequate to support the role of B vitamins in reducing cardiovascular risk .

- Dementia and cognitive function

- Researchers have long been interested in the potential connection between vitamin B12 deficiency and dementia . A deficiency in vitamin B12 causes an accumulation of homocysteine in the blood and might decrease levels of substances needed to metabolize neurotransmitters . Observational studies show positive associations between elevated homocysteine levels and the incidence of both Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. Low vitamin B12 status has also been positively associated with cognitive decline.

- Despite evidence that vitamin B12 lowers homocysteine levels and correlations between low vitamin B12 levels and cognitive decline, research has not shown that vitamin B12 has an independent effect on cognition. In one randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 195 subjects aged 70 years or older with no or moderate cognitive impairment received 1,000 mcg vitamin B12, 1,000 mcg vitamin B12 plus 400 mcg folic acid, or a placebo for 24 weeks. Treatment with vitamin B12 plus folic acid reduced homocysteine concentrations by 36%, but neither vitamin B12 treatment nor vitamin B12 plus folic acid treatment improved cognitive function.

- Women at high risk of cardiovascular disease who participated in the Women’s Antioxidant and Folic Acid Cardiovascular Study were randomly assigned to receive daily supplements containing 1 mg vitamin B12, 2.5 mg folic acid, and 50 mg vitamin B6, or a placebo. After a mean of 1.2 years, B-vitamin supplementation did not affect the mean cognitive change from baseline compared with placebo. However, in a subset of women with low baseline dietary intake of B vitamins, supplementation significantly slowed the rate of cognitive decline.

- In a trial conducted by the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study consortium that included individuals with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease, daily supplements of 1 mg vitamin B12, 5 mg folic acid, and 25 mg vitamin B6 for 18 months did not slow cognitive decline compared with placebo [80]. Another study found similar results in 142 individuals at risk of dementia who received supplements of 2 mg folic acid and 1 mg vitamin B12 for 12 weeks.

- The authors of two Cochrane reviews and a systematic review of randomized trials of the effects of B vitamins on cognitive function concluded that insufficient evidence is available to show whether vitamin B12 alone or in combination with vitamin B6 or folic acid has an effect on cognitive function or dementia. Additional large clinical trials of vitamin B12 supplementation are needed to assess whether vitamin B12 has a direct effect on cognitive function and dementia.

Energy and endurance

Due to its role in energy metabolism, vitamin B12 is frequently promoted as an energy enhancer and an athletic performance and endurance booster. These claims are based on the fact that correcting the megaloblastic anemia caused by vitamin B12 deficiency should improve the associated symptoms of fatigue and weakness.

However, vitamin B12 supplementation appears to have no beneficial effect on performance in the absence of a nutritional deficit.

Health Risks from Excessive Vitamin B12

The IOM did not establish a UL for vitamin B12 because of its low potential for toxicity. In Dietary Reference Intakes: Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline, the IOM states that “no adverse effects have been associated with excess vitamin B12 intake from food and supplements in healthy individuals”.

Findings from intervention trials support these conclusions. In the NORVIT and HOPE 2 trials, vitamin B12 supplementation (in combination with folic acid and vitamin B6) did not cause any serious adverse events when administered at doses of 0.4 mg for 40 months and 1.0 mg for 5 years.

Interactions with Medications

Vitamin B12 has the potential to interact with certain medications. In addition, several types of medications might adversely affect vitamin B12 levels. A few examples are provided below.

Individuals taking these and other medications on a regular basis should discuss their vitamin B12 status with their healthcare providers.

Chloramphenicol

Chloramphenicol is a bacteriostatic antibiotic. Limited evidence from case reports indicates that chloramphenicol can interfere with the red blood cell response to supplemental vitamin B12 in some patients.

Proton pump inhibitors

Proton pump inhibitors, such as omeprazole and lansoprazole, are used to treat gastroesophageal reflux disease and peptic ulcer disease. These drugs can interfere with vitamin B12 absorption from food by slowing the release of gastric acid into the stomach.

However, the evidence is conflicting on whether proton pump inhibitor use affects vitamin B12 status. As a precaution, healthcare providers should monitor vitamin B12 status in patients taking proton pump inhibitors for prolonged periods.

H2 receptor antagonists

Histamine H2 receptor antagonists, used to treat peptic ulcer disease, include cimetidine, famotidine, and ranitidine. These medications can interfere with the absorption of vitamin B12 from food by slowing the release of hydrochloric acid into the stomach.

Although H2 receptor antagonists have the potential to cause vitamin B12 deficiency, no evidence indicates that they promote vitamin B12 deficiency, even after long-term use. Clinically significant effects may be more likely in patients with inadequate vitamin B12 stores, especially those using H2 receptor antagonists continuously for more than 2 years.

Metformin

- Metformin, a hypoglycemic agent used to treat diabetes, might reduce the absorption of vitamin B12, possibly through alterations in intestinal mobility, increased bacterial overgrowth, or alterations in the calcium-dependent uptake by ileal cells of the vitamin B12-intrinsic factor complex. Small studies and case reports suggest that 10%–30% of patients who take metformin have reduced vitamin B12 absorption.

- In a randomized, placebo-controlled trial in patients with type 2 diabetes, metformin treatment for 4.3 years significantly decreased vitamin B12 levels by 19% and raised the risk of vitamin B12 deficiency by 7.2% compared with placebo.

- Some studies suggest that supplemental calcium might help improve the vitamin B12 malabsorption caused by metformin, but not all researchers agree.

- The Dietary Guidelines for Americans describe a healthy eating pattern as one that:

- Fish and red meat are excellent sources of vitamin B12. Poultry and eggs also contain vitamin B12.

- Includes a variety of vegetables, fruits, whole grains, fat-free or low-fat milk and milk products, and oils.

- Milk and milk products are good sources of vitamin B12. Many ready-to-eat breakfast cereals are fortified with vitamin B12.

- Includes a variety of protein foods, including seafood, lean meats and poultry, eggs, legumes (beans and peas), nuts, seeds, and soy products.

- Limits saturated and trans fats, added sugars, and sodium.

- Stays within your daily calorie needs.

Signs and Symptoms of vitamin B 12 deficiency:

Tingling hands or feet:

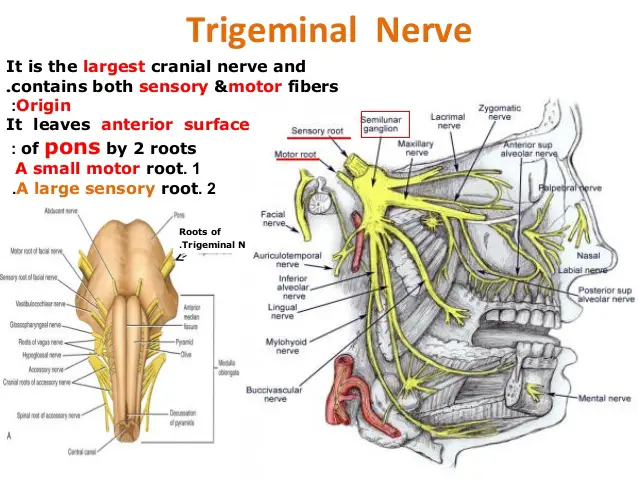

Vitamin B-12 deficiency may cause “pins and needles” in the hands or feet. This symptom occurs because the vitamin plays a crucial role in the nervous system, and its absence can cause people to develop nerve conduction problems or nerve damage.

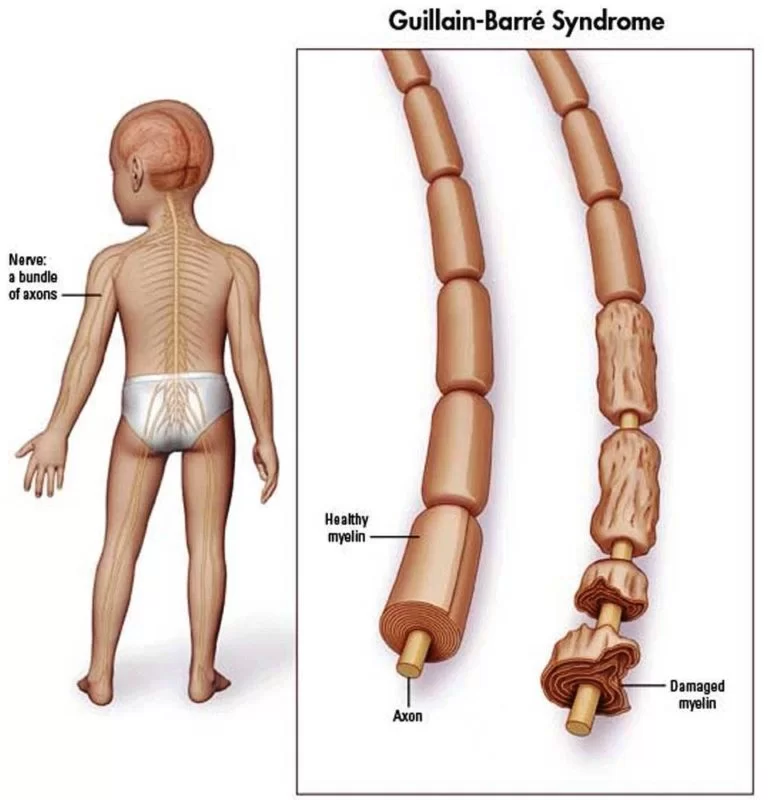

In the nervous system, vitamin B-12 helps produce a substance called myelin. Myelin is a protective coating that shields the nerves and helps them transmit sensations.

People who are vitamin B-12 deficient may not produce enough myelin to coat their nerves. Without this coating, nerves can become damaged.

Problems are more common in the nerves in the hands and feet, which are called peripheral nerves. Peripheral nerve damage may lead to tingling in these parts of the body.

Trouble walking

Over time, peripheral nerve damage resulting from vitamin B-12 deficiency can lead to movement problems.

Numbness in the feet and limbs may make it hard for a person to walk without support. They may also experience muscle weakness and diminished reflexes.

Pale skin

Pale or yellow skin, called jaundice, may be a symptom of vitamin B-12 deficiency.

Jaundice develops when a person’s body is not able to produce enough red blood cells. Red blood cells circulating under the skin provide it with its normal color. Without enough of these cells, the skin may look pale.

Vitamin B-12 plays a role in the production of red blood cells. A vitamin B-12 deficiency can cause a lack of red blood cells, or megaloblastic anemia, which has an association with jaundice.

This type of anemia can also weaken the red blood cells, which the body then breaks down more quickly. When the liver breaks down red blood cells, it releases bilirubin. Bilirubin is a brownish substance that gives the skin the yellowish tone that is characteristic of jaundice.

Fatigue

Megaloblastic anemia due to vitamin B-12 deficiency may lead to a person feeling fatigued.

Without enough red blood cells to carry oxygen around the body, a person can feel extremely tired

Fast heart rate

A fast heart rate and shortness of breath may be symptoms of vitamin B-12 deficiency.

A fast heart rate may be a symptom of vitamin B-12 deficiency.

The heart may start to beat faster to make up for the reduced number of red blood cells in the body.

Anemia puts pressure on the heart to push a higher volume of blood around the body and to do it more quickly. This response is the body’s way of trying to ensure that enough oxygen circulates through all of the body’s systems and reaches all the organs.

Shortness of breath

Anemia that results from vitamin B-12 deficiency may cause a person to feel a little short of breath. It is possible to link this to a lack of red blood cells and a fast heartbeat.

Anyone who is experiencing real difficulty breathing should see a doctor straight away.

Mouth pain

Vitamin B-12 affects oral health. As a result, being deficient in vitamin B-12 may cause the following mouth problems:

glossitis, which causes swollen, smooth, red tongue mouth ulcers and a burning sensation in the mouth

These symptoms occur because vitamin B-12 deficiency causes a reduction in red blood cell production, which results in less oxygen reaching the tongue.

Problems thinking or reasoning

Vitamin B-12 deficiency may cause problems with thinking, which doctors refer to as cognitive impairment. These issues include difficulty thinking or reasoning and memory loss.

One study even linked low vitamin B-12 levels to an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, and Parkinson’s disease.

The reduced amount of oxygen reaching the brain might be to blame for the thinking and reasoning problems. Irritability

Being deficient in vitamin B-12 can affect a person’s mood, potentially causing irritability or depression.

There is a need for more research into the link between vitamin B-12 and mental health. One theory is that vitamin B-12 helps break down a brain chemical called homocysteine. Having too much homocysteine in the brain may cause mental health problems

Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea

Vitamin B-12 deficiency can affect the digestive tract.

A lack of red blood cells means that not enough oxygen reaches the gut. Insufficient oxygen here may lead to a person both feeling and being sick. It may also cause diarrhea.Decreased appetite and weight loss

As a result of digestive problems, such as nausea, people with vitamin B-12 deficiency may lose their appetite. A decreased appetite can lead to weight loss in the long term.

Causes of Vitamin B 12 deficiency

Eating a vegan diet increases the risk of vitamin B-12 deficiency.

Even if a person gets enough vitamin B-12 in their diet, some underlying health conditions can affect the absorption of vitamin B-12 in the gut.

These conditions include:

- Crohn’s disease

- celiac disease

- atrophic gastritis

- pernicious anemia

The following factors make a person more likely to have a vitamin B-12 deficiency:

being older, because a person becomes less able to absorb B-12 as they age by eating a vegetarian or vegan diet

taking anti-acid medication for an extended period of weight loss surgery or other stomach surgery, can affect how the digestive system absorbs vitamin B-12

Treatment and prevention

Most people can get enough vitamin B-12 from dietary sources. For those who cannot, a doctor may prescribe or recommend B-12 supplements. People can also get B-12 supplements from drug stores or choose between brands online.

Most multivitamins contain vitamin B-12. People can take B-12 supplements in the form of oral tablets, sublingual tablets that dissolve under the tongue, or injections. A doctor can provide advice on the correct dosage of this vitamin.

People who have trouble absorbing vitamin B-12 may need shots of the vitamin to treat their deficiency.

A doctor can advise people on the best way to prevent vitamin B-12 deficiency, depending on their dietary choices and health.

Side effects

The side effects of taking vitamin B-12 are very limited. It is not considered to be toxic in high quantities, and even 1000-mcg doses are not thought to be harmful.

There have been no reports of an adverse reaction to B-12 since 2001 when a person in Germany reported rosacea as a result of a B-12 supplement. Cases of B-12-triggered acne have also been reported.

Cyanocobalamin is an injectable form of the supplement that contains traces of cyanide, a poisonous substance. As a result, some concerns have been raised about its possible effects. However, many fruits and vegetables contain these traces, and it is not considered a significant health risk.

This type of supplement is not, however, recommended for people with kidney disease.

3 Comments