Pain Management

What is pain management?

Pain is a universal experience that everyone encounters at some point in their lives. It serves as the most prevalent symptom associated with potentially thousands of injuries, diseases, disorders, and conditions that individuals may encounter throughout their lifetime.

Additionally, pain can emerge as a consequence of various medical treatments and interventions. Pain can manifest as a transient discomfort that subsides as one heals, known as acute pain, or it can persist for extended periods, lasting for months or even years, termed chronic pain.

To address and alleviate the burden of pain, individuals turn to pain management specialists who employ a range of strategies, including medications, medical procedures, therapeutic exercises, and counseling. The optimal approach may involve a single method or a combination of several, tailored to the individual’s specific needs. Pain management services are typically accessible through pain clinics, healthcare provider’s offices, or hospitals.

It’s important to acknowledge that the extent of relief from pain can vary depending on its cause and nature. In some instances, complete relief may not be attainable, and immediate improvement may not be achievable. Nonetheless, healthcare providers collaborate closely with patients to adapt and refine their pain management plans, aiming to enhance their overall well-being.

What is Pain?

Pain represents an uncomfortable sensation that serves as a warning sign of actual or potential injury to the body.

It’s worth noting that pain stands as the primary motivator for people seeking medical attention.

Pain can manifest in various forms, such as sharp or dull, intermittent or constant, throbbing or steady. At times, pain can be challenging to articulate accurately. It might be localized to a specific point or encompass a broader area. The intensity of pain spans a wide spectrum, ranging from mild discomfort to excruciating agony.

Individuals exhibit significant variations in their pain tolerance. One person might struggle with the pain of a minor cut or bruise, while another can endure the pain resulting from a major accident or deep wound. The capacity to endure pain is influenced by factors like mood, personality, and context. For instance, during the excitement of a sports match, an athlete might not notice a significant bruise but could become acutely aware of the pain afterward, especially if their team lost.

Pathways of Pain:

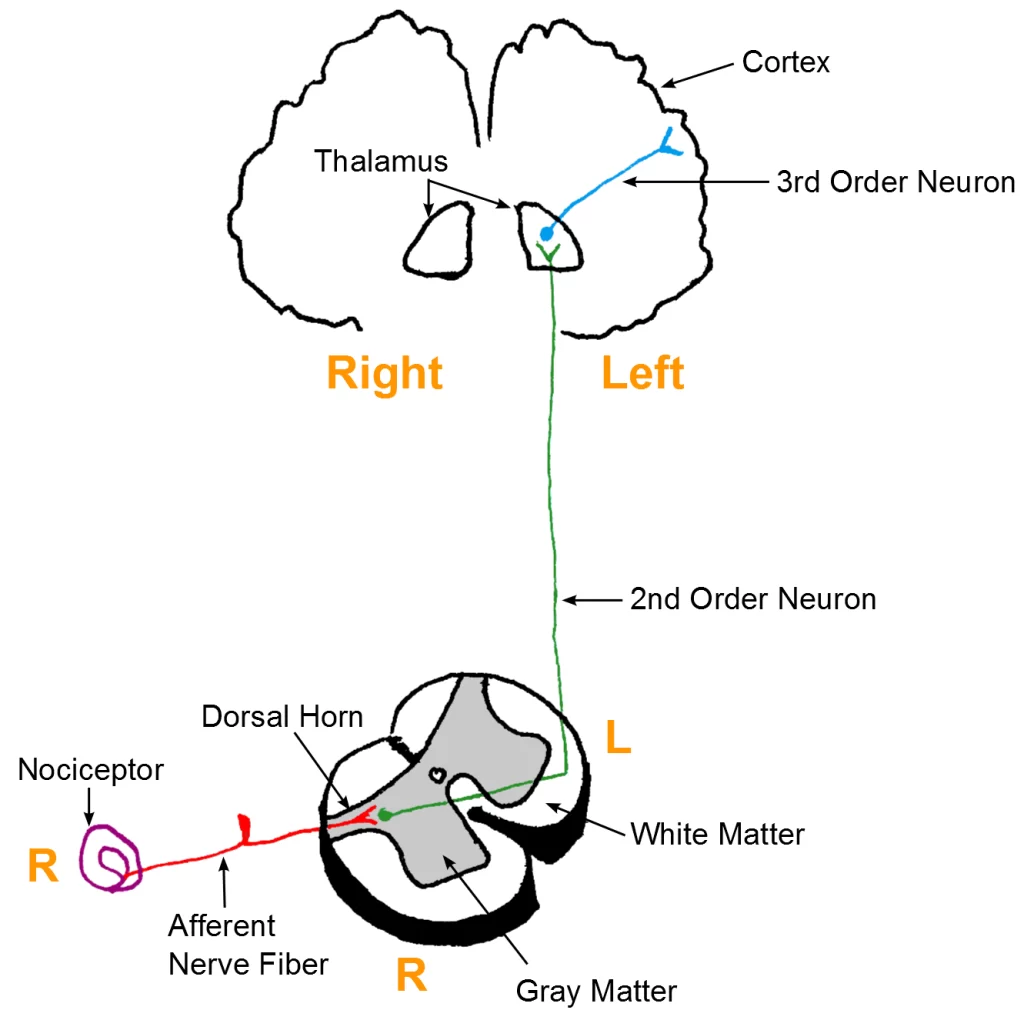

Pain stemming from an injury initiates specialized pain receptors distributed throughout the body. These pain receptors transmit signals as electrical impulses along nerves, traveling to the spinal cord and then upward to the brain. Occasionally, the signal prompts a reflex response, as seen in the reflex arc, where the spinal cord immediately sends a signal back along motor nerves to the source of pain, triggering muscle contraction without involving the brain. For instance, when someone accidentally touches something scalding hot, they instinctively withdraw their hand.

This reflexive action helps prevent lasting harm. Simultaneously, the pain signal is relayed to the brain. Only when the brain processes and interprets this signal as pain does an individual become consciously aware of it.

It’s important to note that pain receptors and their nerve pathways differ across various parts of the body. Consequently, the sensation of pain varies depending on the type and location of the injury. For example, the skin is rich in pain receptors, capable of conveying precise information about the location and nature of an injury whether it’s a sharp cut from a knife or a dull ache from pressure, heat, cold, or itching. Conversely, internal organs like the intestines possess fewer and less precise pain receptors.

The intestines can endure pinching, cutting, or burning without generating a pain signal. However, sensations such as stretching and pressure can elicit severe intestinal pain, even from seemingly innocuous causes like a trapped gas bubble. The brain struggles to pinpoint the exact source of this intestinal pain, which tends to be diffuse and challenging to localize.

Guiding Pain Treatment:

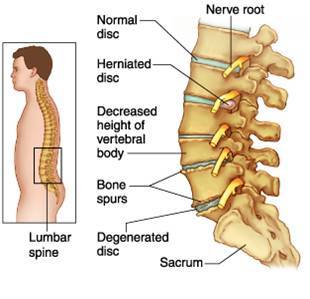

The approach to pain treatment hinges on several factors, including the history of the pain, its intensity, duration, exacerbating and alleviating factors, and the structures involved in causing the pain.

For pain to originate from a particular structure, that structure must possess a nerve supply, and be susceptible to injury, and stimulation of the structure should trigger pain. In most cases of interventional pain treatment, the premise is that a specific bodily structure with sensory nerves is responsible for generating the pain. Pain management plays a critical role in identifying the precise source of the issue and determining the most appropriate treatment.

Medical procedures like fluoroscopy, an X-ray-guided visualization technique, are often employed to aid physicians in accurately locating the injection site, ensuring that the medication reaches the precise target area. Similarly, ultrasound is used to identify structures and guide injections with precision.

What are the types of pain?

Pain is a broad term encompassing any unpleasant or discomforting sensation experienced in the body. It’s diverse in its origins and manifestations, which can be categorized into eight distinct types, aiding in the effective management of pain:

- Acute Pain: This form of pain arises suddenly and typically subsides within a short duration, ranging from minutes to a few days, occasionally extending to a month or two. Acute pain is often triggered by specific events or injuries, such as fractures, accidents, falls, burns, cuts, dental procedures, labor, or surgery.

- Chronic Pain: Chronic pain persists for over six months, frequently occurring on most days. It may originate from an initial episode of acute pain but endures long after the initial injury or event has healed. Conditions associated with chronic pain vary in severity and encompass arthritis, back pain, cancer, circulatory issues, diabetes, fibromyalgia, and headaches. Chronic pain can significantly impact an individual’s quality of life, potentially hindering their ability to work, and engage in physical activities, and even leading to feelings of depression or social isolation.

- Breakthrough Pain: Also known as a pain flare, breakthrough pain is a sudden, intense increase in pain experienced by individuals already taking medications to manage chronic pain conditions like arthritis, cancer, or fibromyalgia. It can occur during activities, coughing, illness, stress, or between doses of pain medication, often manifesting at the same location as chronic pain.

- Bone Pain: Bone pain refers to tenderness, aching, or discomfort in one or more bones, persisting during both rest and physical activity. It is commonly associated with conditions affecting bone structure or function, such as cancer, fractures, infections, leukemia, mineral deficiencies, sickle cell anemia, or osteoporosis. Additionally, many pregnant women experience pelvic girdle pain.

- Nerve Pain: Nerve pain, also known as neuralgia or neuropathic pain, arises from nerve damage or inflammation. It is often described as sharp, shooting, burning, or stabbing, with some likening it to electric shocks, and it tends to worsen at night. People with nerve pain may become hypersensitive to cold and experience discomfort from even the slightest touch. Common causes include alcoholism, brain or spinal cord injuries, cancer, circulation problems, diabetes, herpes zoster (shingles), limb amputation, multiple sclerosis, stroke, or vitamin B12 deficiency.

- Phantom Pain: Phantom pain is the sensation of pain originating from a body part that no longer exists, commonly observed in individuals who have undergone limb amputations. It various from phantom limb experience, which is generally painless. Modern understanding recognizes phantom pain as a real sensation originating in the spinal cord and brain. Although it often improves with time, managing phantom pain can pose challenges for some individuals.

- Soft Tissue Pain: This discomfort arises from damage or inflammation of muscles, tissues, or ligaments and may be accompanied by swelling or bruising. Conditions leading to soft tissue pain encompass back or neck pain, bursitis, fibromyalgia, rotator cuff injuries, sciatica, sports-related injuries (like sprains or strains), and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) syndrome.

- Referred Pain: Referred pain creates the illusion of originating from a specific location but results from an injury or inflammation in a different structure or organ. For instance, during a heart attack, pain is often felt in the neck, left shoulder, and down the right arm. An injury or inflammation of the pancreas might manifest as constant pain in the upper stomach area that radiates to the back. This phenomenon occurs due to a network of interconnected sensory nerves supplying various tissues, leading the brain to misinterpret the source of pain.

Understanding these diverse pain types is essential in tailoring effective pain management strategies for individuals facing various discomforts and conditions.

Pathophysiology of Pain

- Pain Pathway: The journey of pain begins with nociceptors, specialized receptors that detect harmful chemical, mechanical, or thermal stimuli. These stimuli are then converted into electric signals, known as action potentials. These action potentials travel through C fibers and Aδ fibers, serving as afferent input, to reach the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. From there, secondary nociceptive neurons in the spinothalamic tract carry this afferent input to the thalamus within the central nervous system (CNS). Here, pain perception occurs, and a response is transmitted along efferent pathways, leading to pain modulation and/or a reaction.

- Withdrawal Reflex: The withdrawal reflex is a complex spinal reflex involving multiple synapses. It induces a part of the body to move away from a painful stimulus, such as a hot object. This reflex operates by contracting flexor muscles and relaxing extensor muscles.

Pain Sensitization:

Pain sensitization refers to an abnormal perception of pain resulting from heightened neuronal sensitivity to noxious stimuli (hyperalgesia) and/or a lowered neuronal threshold to typically non-painful stimuli (allodynia). This phenomenon can be triggered by local injury, inflammation, or repetitive stimulation and plays a substantial role in the development and persistence of chronic pain and neuropathic pain conditions like postherpetic neuralgia.

While the complete mechanisms are not yet fully comprehended, the pathophysiology of pain sensitization is believed to involve two primary mechanisms:

- Peripheral Sensitization: In this process, injury, inflammation, or repetitive stimulation of peripheral nociceptive neurons leads to the local release of chemical mediators (e.g., cytokines, nerve growth factors, histamine). Continued exposure to these chemical mediators causes an upregulation of ion channels in the nociceptors, ultimately increasing sensitivity and/or reducing the threshold for these mediators. This heightened sensitivity results in an increase in action potentials and the development of abnormal pain perception. Peripheral sensitization typically resolves once the underlying tissue injury or inflammation heals.

- Central Sensitization: Central sensitization occurs when there is injury and/or inflammation within the CNS itself, such as in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord or the brain. This leads to increased excitability and decreased inhibition within the CNS, and non-nociceptive fibers (e.g., Aβ fibers) are recruited into the nociceptive pathway. This aberrant recruitment contributes to abnormal pain perception. Importantly, central sensitization can persist even after the initial injury or inflammation has resolved. Chronic peripheral pain conditions often play a significant role in the ongoing sensitization of central nociceptive neurons.

What are the Goals of pain management?

Pain, whether chronic like persistent headaches or acute following surgical procedures, is regarded in pain management as a treatable condition. This perspective allows for the application of scientific knowledge and the latest medical advancements to alleviate suffering effectively.

The diverse array of modalities available in contemporary pain management includes medications, interventional treatments such as nerve blocks and spinal cord stimulators, physical therapy, and complementary approaches from alternative medicine.

The primary goal of pain management is to mitigate pain rather than entirely eradicate it. Complete elimination of pain is often unattainable, so the emphasis is on minimizing it. Alongside pain reduction, pain management strives to achieve two other critical objectives:

- Enhancing Function: Pain management seeks to improve the overall functionality of individuals living with chronic pain. This encompasses the restoration of physical capabilities, mobility, and daily activities that may have been disrupted by pain.

- Enhancing Quality of Life: A core aspiration of pain management is to enhance the overall quality of life for patients. This involves not only alleviating physical discomfort but also addressing the emotional and psychological aspects that frequently accompany chronic pain, such as depression and anxiety.

For a patient seeking pain management services, the typical journey may involve the following steps:

- Evaluation: A thorough evaluation of the patient’s pain condition, medical history, and individual needs forms the foundation of a pain management plan.

- Diagnostic Tests: If deemed necessary based on the evaluation, diagnostic tests may be conducted to further assess the underlying causes and factors contributing to the pain.

- Referral to a Surgeon: In cases where diagnostic results and evaluation indicate the need for surgical intervention, patients may be referred to a surgeon for specialized care.

- Interventional Treatments: Depending on the diagnosis, interventional treatments such as injections or spinal cord stimulation may be administered as part of the pain management strategy.

- Physical Therapy: Physical therapy plays a crucial role in enhancing the patient’s range of motion, strength, and readiness to return to their normal activities or work.

- Psychiatry: Dealing with the emotional toll of chronic pain, including depression, anxiety, and related issues, is an integral component of comprehensive pain management.

- Alternative Medicine: Complementary approaches from alternative medicine can be integrated into the treatment plan to provide additional avenues for relief and healing.

Individuals who often benefit most from a pain management program include those who have undergone multiple back surgeries, experienced failed surgical interventions, suffer from neuropathy, or have conditions where surgery is determined to be ineffective for their specific case.

Who can benefit from pain management?

Pain management is a valuable resource for anyone grappling with pain, irrespective of its origin. A well-structured pain management plan can offer relief for individuals experiencing short-term pain, such as the aftermath of an injury or surgery, as well as those enduring long-term pain stemming from chronic health conditions or diseases.

Pain often takes center stage as a primary symptom in a wide spectrum of injuries, infections, and medical conditions. For instance, cancer-related pain can accompany nearly every type of cancer diagnosis, while chest pain is frequently an early indicator of a heart attack, with discomfort potentially radiating to the arms, back, or jaw. Some of the most prevalent conditions linked to pain encompass:

- Arthritis and Joint Injuries: Various forms of arthritis, including osteoarthritis and gout, are notorious for causing intense joint pain. Additionally, orthopedic injuries like a frozen shoulder can impair mobility and result in pain and stiffness.

- Autoimmune Disorders: Conditions like Lupus and Crohn’s disease are autoimmune disorders that prompt the immune system to attack the body itself, often resulting in pain and discomfort.

- Back Problems: A range of issues such as herniated disks and sciatica can lead to back pain and restricted movement.

- Chronic Pain Disorders: Conditions like fibromyalgia, complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), and central pain syndrome can lead to pervasive, widespread pain across the body.

- Endometriosis: This distressing condition occurs when the uterine lining grows outside of the uterine walls, causing abdominal pain and irregular menstrual periods.

- Facial Pain: Conditions like trigeminal neuralgia (TN), dental abscesses, and other oral problems can result in facial pain.

- Headaches: Migraines and cluster headaches can trigger head and neck pain.

- Urinary Tract Issues and Kidney Stones: Kidney stones often cause severe pain as they pass through the urinary system, while interstitial cystitis (painful bladder syndrome) leads to pelvic pain and pressure.

- Neuropathy (Nerve Damage): Damaged nerves can result in pain, tingling, and burning sensations. Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is a familiar instance of neuropathy.

In each of these cases, a personalized pain management plan can play a crucial role in enhancing one’s quality of life and managing the associated discomfort.

Subtypes and Variants of Pain

Referred Pain

- Definition: Referred pain is the perception of pain at a location different from the actual source of the stimulus. Typically, this pain projection occurs onto specific dermatomes or myotomes corresponding to the spinal cord segment involved.

- Common Examples of Referred Pain:

- Right shoulder pain in patients with cholecystitis or perforated peptic ulcer disease.

- Kehr sign: Left shoulder pain linked to diaphragmatic irritation, often due to hemoperitoneum, classically stemming from splenic rupture.

- Left-sided chest and arm pain during a myocardial infarction.

- Periumbilical pain in the initial stages of appendicitis.

- Treatment: Selective treatments may help alleviate referred pain by addressing the underlying pathway.

| Organ | Dermatome | Projection |

| Diaphragm | C4 | Shoulders |

| Heart | T3–4 | Left chest |

| Esophagus | T4–5 | Retrosternal |

| Stomach | T6–9 | Epigastrium |

| Liver, gallbladder | T10–L1 | Right upper quadrant |

| Small bowel | T10–L1 | Periumbilical |

| Colon | T11–L1 | Lower abdomen |

| Bladder | T11–L1 | Suprapubic |

| Kidneys, testicles | T10–L1 | Groin |

Phantom Limb Syndrome

- Definition:

- Phantom Sensation: This is the sensation that the amputated limb still partially or entirely exists.

- Phantom Pain: Refers to the perception of pain in an amputated limb. It encompasses intermittent pain with varying characteristics such as burning, tingling, shooting, itching, squeezing, aching, or electric shock-like sensations.

- Onset typically occurs within days to weeks following amputation, with pain often resolving or diminishing over time.

- Incidence: Commonly observed as a complication after upper or lower extremity amputations.

- Pathophysiology: Phantom limb syndrome arises from the reorganization of the primary somatosensory cortex neurons. These neurons, once responsive to signals from the amputated limb, now respond to signals from adjacent neurons carrying sensations from other body parts.

- Diagnosis: Phantom limb syndrome is diagnosed only after excluding other potential causes of stump pain, such as infection, ischemia, or post-surgical neuroma.

- Treatment: Managing phantom limb syndrome typically involves a multimodal approach, including:

- Mirror therapy

- Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS): An analgesic therapy that modifies pain perception by delivering continuous electrical impulses through skin electrodes.

- NMDA receptor antagonists

- Adjuvant therapy may include tricyclic antidepressants and anticonvulsants.

- Prophylaxis: Perioperative regional anesthesia may be considered as a preventive measure.

Pain Evaluation

To ensure effective pain management, a comprehensive assessment of pain is essential before initiating any treatment.

Pain Assessment:

- Pain Characteristics: This includes determining the location, quality, temporal aspects, and potential triggers of the pain.

- Associated Symptoms: Assess any associated symptoms, such as changes in mobility and strength, which can provide valuable insights into the underlying cause of pain.

- Prior Pain History: Review the patient’s previous pain assessments and treatment experiences to tailor the current approach effectively.

Pain Intensity Assessment:

Pain intensity is a critical aspect of pain assessment and is often quantified using various scales:

- Numeric Rating Scale (NRS): The NRS is the most commonly used pain scale, where patients rate their pain severity on a scale ranging from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable).

- Visual Analog Scale (VAS): VAS utilizes visual equivalents and is suitable, especially for children, who can indicate the severity of their pain by marking on a visual scale.

- Verbal Descriptor Scale: This scale allows patients to describe their pain using words like “mild,” “moderate,” or “severe.”

Impact Assessment:

Evaluate how pain affects various aspects of the patient’s life, including daily activities, sleep, and overall quality of life. Validated scales like the PEG pain scale for chronic pain may be employed to assess this impact.

Utilizing a pain diary for regular documentation of pain intensity can help identify patterns, peaks, and triggers, facilitating treatment optimization.

Assessing Pain in Nonverbal Patients:

Assessing pain in nonverbal patients, such as infants or individuals with communication challenges, can be challenging. In such cases, gather information from caregivers or observers and use specialized pain assessment tools like the nonverbal pain scale.

Addressing Implicit Bias:

Be mindful of implicit bias in pain assessment. Research has shown disparities in pain management based on race and ethnicity. Hispanic and Black patients are sometimes less likely to receive appropriate analgesia compared to White patients, even when reported pain scores are identical. It’s essential to provide equitable pain management based on clinical needs rather than demographic factors.

Pain is Subjective:

Remember that pain is a highly subjective experience, and pain scales are primarily used to assess a patient’s pain and their response to pain management over time. They should not be used to compare pain intensity between different patients, as pain perception can vary widely from person to person.

Analgesics

WHO Analgesic Ladder:

The World Health Organization (WHO) Analgesic Ladder is a 3-step algorithm for the control of acute & chronic pain.

- Regular Analgesics (Modified-release drugs, administered at fixed times and doses)

- Oral administration is preferred for analgesics.

- Administer regularly at fixed intervals, rather than on an as-needed basis.

- Progress through the ladder in a symptom-oriented manner: if the patient still experiences pain, consider advancing to the next step.

- Appropriate PRN Medication (As-needed medication)

- Use short-acting analgesics for pain spikes.

- If PRN medication is needed ≥ 3 times a day, it may indicate inadequate pain relief; review the regular medication.

- Additionally, consider concurrent treatment with adjuvant drugs.

| Pain intensity | Nonopioid analgesics | High-intensity opioids | High intensity opioids | Adjuvant drugs | |

| Stage I | Mild | Involve | Avoid | Avoid | If needed |

| Stage II | Moderate | Involve | Consider | Avoid | If needed |

| Stage III | Severe | Involve | Consider | Consider | If needed |

Non-opioid analgesics are the first-line agents for pain management. Specify them alone for mild to moderate pain & in a mixture with opioids for intense pain.

For both opioid and non-opioid analgesics, use the minimal effective dose for the shortest possible duration to minimize adverse effects. Regular pain intensity assessments should be conducted to evaluate the success of pain management.

Oral Analgesics:

| Oral analgesics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug class | Drug | Important considerations | |

| Nonopioids | Acetaminophen | Acetaminophen | Inactive hepatic disease or liver failure |

| NSAIDs | Aspirin Ibuprofen Diclofenac Naproxen Indomethacin Meloxicam | The chosen first-line analgesics for mild to moderate pain are ibuprofen and naproxen. In patients with PUD and renal illness, use with caution. Low-dose aspirin is an exception for the contraindication in patients with a recent MI and during the perioperative period of CABG. If at all possible, stay away from NSAIDs if you have a bleeding disorder or are getting ready to have surgery or another invasive operation. | |

| Selective COX-2 inhibitor | Celecoxib | Second-line analgesic of choice for mild to severe pain Preferred to NSAIDs in PUD patients Patients who have kidney or cardiovascular illness should use with caution. | |

| Opioids | Oxycodone Hydromorphone Tramadol | Second-line analgesic of choice for mild to severe pain Preferred to NSAIDs in PUD patients Patients who have kidney or cardiovascular illness should use it with caution. | |

| Combination analgesics | Reduce the amount of non-opioid analgesics needed (multimodal pain management) by combining them. In the first 72 hours after starting or increasing the opioid dose, keep an eye out for respiratory depression. In individuals who are unfamiliar with opioids, oxycodone is not advised for either preoperative or postoperative analgesia. As tramadol decreases the seizure threshold, it is not advised for use in people with epilepsy. Contraindications: respiratory distress, gastrointestinal blockage, biliary colic, asthma head trauma. | For the treatment of moderate to severe pain, take into account combination analgesics. When prescribing these combination analgesics, observe the same safety precautions and contraindications for opioids, paracetamol, and NSAIDs. | |

Patients receiving opioid medications upon discharge should receive counseling on the proper use of prescription opioids.

Parenteral Analgesics:

| Drug class | Drug | Important considerations |

| NSAIDs | Ketorolac Diclofenac Ibuprofen | Patients with recent MI and during the perioperative period of CABG are contraindicated. Patients with suspected intestinal perforation, PUD, or hemorrhage should not receive this medication. Avoid using NSAIDs before surgery. Following bowel surgery, is connected to an increased incidence of gastrointestinal anastomotic leakage. Analgesics of choice when biliary colic or pancreatitis is suspected. |

| Opioids | Tramadol Morphine Hydromorphone Fentanyl Buprenorphine | Patients with recent MI and during the perioperative period of CABG are contraindicated. Patients with suspected intestinal perforation, PUD, or haemorrhage should not receive this medication. Avoid using NSAIDs before surgery. Following bowel surgery, is connected to an increased incidence of gastrointestinal anastomotic leakage. Analgesics of choice when biliary colic or pancreatitis is suspected. |

Analgesic Suppositories:

- Acetaminophen

- Indomethacin

- Aspirin

Topical Analgesics:

| Drug | Dose | Indications |

| Lidocaine | Lidocaine patch Lidocaine jelly Lidocaine ointment | Patch: postherpetic neuralgia Jelly: painful urethritis Ointment: mild burns, containing sunburn, abrasions of the skin, & insect bites |

| Diclofenac | Diclofenac patch Diclofenac topical solution or gel | Patch: for acute pain due to minor strains, sprains, and contusions Solution or gel: chronic pain in osteoarthritis |

Adjuvant Analgesics:

Anticonvulsants

Anticonvulsants serve as valuable adjuncts in the management of neuropathic pain. They are typically less effective for acute pain and are more commonly employed for chronic neuropathic pain.

- Gabapentin

- Pregabalin

- Carbamazepine

Muscle Relaxants

Consider muscle relaxants for patients experiencing pain associated with muscle spasticity.

- Cyclobenzaprine

- Methocarbamol

- Baclofen

Antidepressants

Tricyclic antidepressants and SNRIs can be beneficial for chronic pain syndromes and neuropathic pain. The American Society of Anesthesiologists recommends the use of antidepressants for chronic or neuropathic pain in their 2010 guideline, but it’s important to note that only duloxetine is FDA-approved for this indication. The use of all others is considered off-label.

- Tricyclic Antidepressants

- Amitriptyline

- Doxepin

- Clomipramine

- SNRIs

- Duloxetine

- Venlafaxine

Intravenous Patient-Controlled Analgesia:

This is an infusion pump designed to administer additional IV medication in response to a patient’s request.

- Indication: It is primarily used for severe acute pain that is challenging to manage and is expected to be of limited duration.

Management of Analgesic Side Effects:

To mitigate the side effects of analgesics, consider the following approaches:

- Laxatives

- Antiemetics

- Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs): These should be considered for patients who frequently take NSAIDs.

Condition-Specific Analgesia:

Certain medical conditions necessitate tailored pain management strategies. Optimizing the management of the underlying conditions may also reduce the need for analgesics.

For example, in cases of pain related to cancer or other high-morbidity illnesses (e.g., chronic pain associated with sickle cell disease), a comprehensive approach may be required.

Nonpharmacological Analgesia

Multiple nonpharmacological therapies are often employed in combination. Examples include:

Physical Modalities:

Evaluate referral to physiotherapy & occupational therapy.

- Massage therapy

- Thermotherapy (e.g., focused ultrasound)

- Desensitization techniques

- Everyday exercise, for example, walking & exercise therapy for chronic pain. Patients may need analgesics to participate in physical therapy; however, prioritize nonopioid pharmacological therapy initially.

Psychological Modalities:

Consultation with a psychologist as necessary.

- Relaxation techniques

- Biofeedback training

- Progressive muscle relaxation

- Mindfulness practices

- Cognitive behavioral therapy

- Hypnosis

Other Modalities:

- Complementary and alternative medicine

- Acupuncture

- Osteopathic manipulative treatment, for example, spinal manipulation for low back pain and tension headache

- Mind-body techniques (e.g., yoga, tai chi)

- Neuromodulation and nerve ablation techniques

Management of Acute Pain

Approach:

- Swiftly provide appropriate analgesia for severe acute pain.

- Utilize a pain intensity scale to assess the severity of pain.

- Document recent analgesic usage, including the type and dosage.

- Customize the treatment plan to suit the patient, the underlying condition, and the care setting.

- Use the WHO analgesic ladder as a guiding framework.

- Whenever feasible, maximize the use of nonpharmacological and nonopioid methods for pain relief.

Choice of Analgesics for Acute Pain:

| Opioids likely needed | Nonopioid analgesics likely as impactful as opioids | |

| Injuries | Opioids likely required Major trauma | Lower back pain Neck pain Soft tissue injuries (e.g., sprain, bursitis) |

| Surgery | Crush injuries Burns Major surgery | Minor surgery |

| Other medical conditions | Severe pain PLUS Contraindications to NSAIDs | Odontalgia Renal colic Headaches (including migraine) |

Administer acute pain management promptly, as delaying it does not enhance the accuracy of a physical examination.

Opioids for Acute Pain:

Prescribe opioids for acute pain only when the benefits clearly outweigh the risks.

- Prescribing Principles:

- Prefer immediate-release opioids over extended-release or long-acting formulations.

- Initiate treatment with the lowest effective dose.

- Prescribe PRN (as-needed) doses rather than scheduled doses.

- Limit the duration of the opioid prescription to the anticipated duration of severe pain.

- Reassess the risk-benefit balance if there is a need for dosage escalation.

Management of Acute-on-Chronic Pain:

Effectively managing acute-on-chronic pain requires a high degree of empathy and expertise.

General Principles

Adhere to local departmental protocols if available.

- Establish clear treatment objectives.

- The primary aim when addressing an acute episode is to enable the patient to return to their baseline level of functioning.

- While complete pain relief may not always be attainable, significant improvement is the goal.

- Conduct a comprehensive pain assessment and review the existing care plans.

- Whenever possible, consult with the healthcare provider responsible for long-term pain management.

- Identify and address reversible causes of pain, such as:

- Comorbid conditions (e.g., renal colic in patients with chronic back pain).

- Episodes of recurrent conditions (e.g., vasoocclusive crisis in sickle cell disease patients).

- Conditions affecting the metabolism of pain medications (e.g., malabsorption).

- Consider systemic obstacles that may hinder access to treatment.

- If no reversible cause is found, contemplate hospital admission for tailored management in patients with advancing terminal illnesses.

Management of Acute-on-Chronic Pain in Hospital Settings:

For patients already on an opioid regimen experiencing uncontrolled pain:

- Give preference to the addition of nonopioid analgesics (e.g., NSAIDs, acetaminophen, or adjuvant analgesics).

- If additional opioids are deemed necessary, match the duration of opioid treatment to the expected duration of severe pain.

- Individualized therapy is strongly recommended for patients with conditions like sickle cell disease, and cancer and those requiring palliative care and/or end-of-life care.

- Engage the patient’s primary healthcare provider in treatment decisions whenever feasible, and be vigilant about the potential for prescription diversion by other healthcare providers.

Pain Management in the Emergency Department:

- Severe Pain:

- When addressing severe pain, follow the approach for acute pain to determine the appropriate analgesic.

- Continuously reassess the severity of pain, with more frequent evaluations if necessary.

- For emergency procedures, contemplate the use of analgesics for procedural sedation.

- Consider the use of a subanesthetic ketamine infusion either as a standalone treatment or as an adjunct to opioids.

- Extremity Injuries:

- Provide ice, elevation, and immobilization as indicated for extremity injuries.

- Administer initial parenteral analgesics for pain resulting from an acute deformity (e.g., fracture, dislocation) that remains unresponsive to immobilization.

- Explore the possibility of using local anesthesia or regional anesthesia for localized pain relief.

- Minimizing Undertreatment:

- Pain among ED patients can be inadequately managed for various reasons, including communication barriers, atypical presentations, and implicit biases.

- Patients at an elevated risk of undertreatment include children, individuals from diverse cultural or linguistic backgrounds, and those with neurocognitive disorders.

- Ambulatory Opioid Prescriptions:

- Limit the duration of ambulatory opioid prescriptions to less than 3–5 days.

- Facilitate rapid follow-up with a primary healthcare provider to allow for dosage adjustments.

Management of Chronic Noncancer Pain

Approach:

The following guidelines pertain to the management of chronic and subacute pain not associated with cancer, sickle cell disease, or other high-morbidity conditions. Separate approaches are detailed for pain related to those conditions in the context of acute pain management and acute-on-chronic pain management.

- Initiate an initial assessment of the patient’s condition.

- Optimize the following aspects as necessary:

- Address comorbid mental health conditions.

- Implement condition-specific pain management strategies.

- Offer patient education on chronic pain management.

- Consider the possibility of enrolling patients in a pain management program (PMP).

- Adhering to the WHO analgesic ladder approach, commence nonopioid management for chronic pain.

- Regularly reassess the effectiveness of the treatment using a validated tool that assesses pain and functioning, such as the PEG pain scale.

- If the pain proves refractory, contemplate the initiation of opioid therapy only when the benefits clearly outweigh the risks.

- Establish treatment goals and an opioid exit strategy before commencing opioid therapy.

- Continue nonopioid remedy in conjunction with opioid treatment.

- Avoid rapid tapering or abrupt discontinuation of opioid therapy once initiated.

Implement a biopsychosocial model of medical care as an integral part of chronic noncancer pain management.

Utilize palliative pain management strategies for pain associated with cancer, sickle cell disease, or other high-morbidity conditions.

Strive to eliminate disparities in chronic pain management, particularly in relation to racial and ethnic factors.

Initial Assessment:

Commence the assessment with a comprehensive approach that includes:

- Obtaining a thorough medical history and conducting a physical examination, which should cover:

- Evaluation of pain and functioning, preferably employing a validated scale such as the PEG pain scale.

- Examination of social determinants of fitness, psychosocial well-being, & other potentially involved aspects.

- Execute a comprehensive review of the medications of individuals.

- Consider the necessity for imaging and further diagnostic studies as follows:

- To rule out serious underlying pathology, especially for patients presenting with neurological deficits.

- To identify conditions that necessitate specific management, such as considering joint replacement for severe hip osteoarthritis.

Indications for Referral:

Patients with the following criteria should be referred to a pain management specialist:

- Age less than 18 years

- Pregnant individuals

- Complex regional pain syndrome

- A history of substance use disorder

- Requiring high morphine milligram equivalent (MME) prescriptions

- Experiencing refractory or severe pain

- In need of interventional pain management

Patients who do not meet the criteria for referral to a pain management specialist can typically be managed by a primary care clinician.

Patient Education:

- Ensure patients have a clear understanding of their diagnosis and how to manage their condition effectively.

- Provide pain neuroscience education to enhance their comprehension of the pain experience.

- Manage the patient’s expectations by explaining:

- The potential timeline for pain improvement may take weeks to months in response to treatment.

- Realistic goals, such as pain reduction rather than complete elimination, and improved functionality.

- The stepwise approach to managing chronic pain.

- Educate patients on the appropriate timing for medication use in pain management.

- Support patients in developing a self-management approach to cope with their condition effectively.

Nonopioid Management:

For the management of chronic noncancer pain, a combination of multimodal nonpharmacological analgesia and various nonopioid pharmacotherapy options can be employed. To determine the most appropriate pharmacotherapy:

- Begin by assessing for any contraindications that may affect treatment choices.

- Evaluate the presence of hepatic and/or renal impairment to guide medication selection and dosing.

- Consider any reported adverse effects from previous therapies to avoid medications with a history of intolerable side effects.

- Account for the pharmacology of medications when dealing with older adults to minimize the risk of adverse effects.

- Identify the type and frequency of the pain experienced by the patient, which can guide medication selection:

- For daily pain, contemplate the use of regularly scheduled nonopioid oral analgesics.

- For breakthrough pain, consider as-needed nonopioid oral analgesics.

- In cases of neuropathic pain, reflect on the use of regular adjuvant analgesics (e.g., anticonvulsants, antidepressants) or topical applications like lidocaine or capsaicin.

- Joint pain may warrant intraarticular glucocorticoid injections.

- Radiculopathy could be managed with epidural glucocorticoid injections.

It’s important to note that there is currently insufficient evidence to support the use of cannabis or cannabinoids for chronic pain management. If considering such treatment, it is imperative to check local laws and regulations before prescribing.

Opioid Management:

Initiating Opioid Therapy

- Begin with a comprehensive evaluation of chronic noncancer pain.

- Ensure that nonopioid therapies for chronic noncancer pain have been maximized, and alternative treatment options have been considered and trialed.

- Refer to institutional and state guidelines to determine indications for opioid prescribing.

- Assess if the patient has contraindications to opioids or risk factors for opioid-related harm.

- Engage in a thorough discussion with the patient about the benefits and risks of opioid therapy, ensuring that the benefits outweigh the risks given the type of pain and treatment goals.

- Benefits may include a possible minor reduction in pain.

- Risks include adverse effects of opioids, the potential development of opioid use disorder, the possibility of worsening pain due to opioid-induced hyperalgesia, and potential impacts on employment opportunities, particularly in safety-critical jobs.

- If an opioid prescription is deemed appropriate, follow risk mitigation practices and make sure patients are aware that chronic opioid use can interfere with employment opportunities, especially in safety-critical jobs.

Before initiating opioid therapy, conduct a thorough patient history, screen for comorbid mental health conditions, and perform medication reconciliation to assess patient suitability for opioid therapy and to reduce modifiable risk factors.

Risk Mitigation

Consider risk mitigation for opioid prescribing before starting opioids and at each follow-up appointment

- Estimate for the evolution of contraindications to opioids/risk factors for opioid-related damage.

- Review state and federal laws related to prescribing controlled substances, utilize the state’s prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP), and follow principles of prescribing for older adults, if relevant.

- Prescribe naloxone and provide education on its use if required by state law or if there are risk factors for opioid overdose in the patient or household members or if sleep-disordered breathing is present.

- Counsel patients on the proper use of prescription opioids.

- Consider referral to a pain specialist and/or the use of buprenorphine for pain management in patients who require long-term daily opioids, are unable to taper or discontinue opioids, or are in danger of opioid usage disorder/have a history of opioid usage illness.

- Avoid concurrent use of opioids and sedative-hypnotic medications (e.g., benzodiazepines, sleeping aids, muscle relaxants), or prescribe with extreme caution.

Ensure individuals with risk factors for opioid overdose have been furnished with naloxone & apprised on how to utilize it.

Prescribing more than a 90-day supply of opioids is associated with a dose-dependent increase in the risk of adverse effects of opioid use, including opioid use disorder.

Managing Aberrant Drug-Related Behaviors

Identify and address aberrant drug-related behaviors, which may suggest abuse, misuse, or diversion of opioids.

- Concerning behaviors include obtaining medication from nonmedical sources, requesting prescriptions early, frequently reporting lost prescriptions, missing appointments at which no opioid refill is anticipated, obtaining prescriptions from multiple providers, and seeking medications in the emergency department.

- Diagnose & manage substance usage conditions & opioid usage illness utilizing a multidisciplinary group. Individuals with unusual drug-related manners shouldn’t be removed from care unless they are damaging/threatening.

Urine Drug Monitoring for Opioid Therapy

- Consider urine toxicology screening before starting opioid therapy and at least annually thereafter.

- Communicate clearly with patients to reduce misunderstandings, explain urine drug monitoring procedures, and emphasize their role in maintaining patient safety.

- Ask nonjudgmental questions about the nature and timing of all recent substance use before ordering a test.

- Interpret results with care, understanding that screening immunoassays have limitations.

- If outcomes are unexplained & will involve management, acquire confirmatory testing.

- Do not use results punitively (e.g., discontinuation of opioids or discharge from practice).

Initiating Opioid Therapy

- Establish a clear treatment plan using shared decision-making, including how and when treatment efficacy will be assessed (e.g., improvements in functioning using the PEG pain scale) and an opioid exit strategy outlining how opioids will be discontinued or how to transition to medication-assisted treatment if the risks outweigh the benefits.

- Create a controlled substance agreement and ensure informed consent is obtained.

- Provide anticipatory guidance to help patients avoid the adverse effects of opioid use.

- Determine dosing and frequency based on opioid pharmacology, favoring short-acting over long-acting formulations.

- Begin with a low dose & titrate to the lowest useful dose.

- For patients with hepatic or renal impairment, consider longer dosing intervals.

- Prescribe opioids as needed rather than scheduling doses.

- Develop a plan for events requiring acute-on-chronic pain management.

- Follow up within 1–4 weeks after initiating therapy to assess improved functioning and pain control.

Ongoing Opioid Therapy

- Conduct regular follow-ups, at least every 3 months, to evaluate efficacy and safety, with more frequent follow-ups for patients at high risk of overdose or misuse.

- Continue to maximize nonopioid management of chronic noncancer pain.

- Adhere to risk mitigation practices for opioid prescribing at every visit, including consideration of urine drug monitoring for opioid therapy at least annually.

- Maintain accurate records at every visit, including calculated daily MME, average daily pain level, functional assessment (e.g., ability to perform ADLs, PEG pain scale score), adverse effects, and documentation of aberrant drug-related behaviors.

Avoid converting from immediate-release to extended-release opioids unless pain is ongoing, severe, and constant or the patient has opioid tolerance when relevant.

Prescribing more than a 90-day supply of opioids is unlikely to improve pain and increase the risk of adverse effects of opioids.

Tapering Opioid Therapy

The decision to taper chronic opioid therapy (and possibly discontinue it) should be made individually, using shared decision-making to weigh the benefits and risks of opioid therapy.

- Indications for tapering may include patient request, resolution of pain, lack of response to therapy (e.g., inadequate improvement in quality of life, function, or pain scores), escalating dosages without improvement, adverse effects impacting quality of life, evidence of diversion or misuse (aberrant drug-related behaviors), overdose event or concern for impending overdose, and risk factors for opioid-related harm.

- Use a multidisciplinary approach and avoid rapid tapering and sudden discontinuation.

- Inform patients that pain may initially worsen during the tapering process.

- Begin by reducing the dose per administration and gradually increase the dosing interval as the lowest dose per administration is achieved.

- Taper at a rate appropriate for the duration of opioid use:

- Taper at ≤ 10% of the original dose per week for use of < 1 year.

- Taper at ≤ 10% of the original dose per month for use of ≥ 1 year.

- Slow the taper if withdrawal symptoms develop.

- Taper at a rate appropriate for the duration of opioid use:

- Follow up monthly during the tapering process and consider the patient’s wishes to slow or pause the taper.

- Evaluate and manage complications of opioid tapering, including opioid withdrawal symptoms, worsening pain, and unmasking opioid use disorder.

Prescribe naloxone to patients undergoing opioid tapering to mitigate the risk of overdose due to decreased tolerance.

Inform individuals that they are at a raised chance for overdose while & briefly after tapering due to because of reduced patience.

Most patients on long-term opioid therapy who agree to taper or discontinue opioids experience overall satisfaction, improved quality of life, and no increase in pain, though they may experience short-term effects such as hyperalgesia, insomnia, and agitation.

- Manage complications of opioid tapering, including the development of opioid withdrawal symptoms, inability to taper or discontinue opioids due to ongoing pain, and unmasking opioid use disorder, involving mental health professionals when needed.

Pain in Critically Ill Patients

Assessment of pain in the ICU:

Patients in the ICU are typically unable to communicate and require specialized pain scales.

- Behavioral Pain Scale:

- Utilized to determine aches in critically ill individuals on automated ventilation.

- Evaluates three items: facial expression, movement of the upper limbs, and mechanical ventilation compliance.

- A score of ≥ 5 points indicates significant pain.

- Critical Care Pain Observation Tool (CCPOT):

- Utilized to recognize pain in critically ill individuals.

- Evaluates four items: facial expressions, body movements, ventilator compliance in intubated patients or vocalization in non-intubated patients, and muscle tension.

- A score of ≥ 3 points indicates significant pain.

For subjective grading of pain severity by the patient:

| Behavioral pain scale score | CCPOT score | |

| Facial expression | 1 point for relaxed 2 points for partially tightened 3 points for fully tightened | 0 points for relaxed 1 point for tense 2 points for grimacing |

| Movement | Upper limbs 1 point for no movement 2 points for partially bent 3 points for completely flexing with a finger 4 points for permanently retracted | Body 0 points for no movement or normal 1 point for protection 2 points for restless or agitated |

| Muscle tension | 0 points for relaxed 1 point for rigid or tense 2 points for very rigid/immobile | |

| Automated ventilation observation | 1 point for tolerating action 2 points for coughing, but accepting most of the period 3 points for fighting ventilator 4 points for being unable to control ventilation | Intubated patients 0 points for tolerating normally 1 point tolerating but coughing 2 points for fighting the ventilator |

| Vocalization for extubated patients | 0 points normal tone or no sound 1 point for moaning or sighing 2 points for crying or sobbing |

Pain management:

- Preemptive analgesia for extubation and invasive procedures.

- Multimodal analgesia depends on the severity and type of pain.

- Use the lowest effective dose of IV opioids as first-line treatment.

- Consider adjuvant NSAIDs.

- Gabapentin or carbamazepine can be considered in case of neuropathic pain.

- Regard utilizing constant infusions/regular amounts of analgesics.

- Regularly assess the severity of pain and the response to analgesia.

Be knowledgeable of the adverse impact of opioids, for example, delirium, CNS depression, and tolerance/NSAID therapy.

Pain in Neonates and Infants:

- Background:

- Pain pathways develop by the 20th week of gestation.

- Newborn & preterm babies are susceptible to pain & stress.

- Procedural Pain:

- Pain and stress resulting from medical procedures such as IV cannulation, venipuncture, finger prick, heel lance, lumbar puncture, and bone marrow aspiration.

- Common in pediatric ICU patients, preterm neonates, and children with malignancy.

- Nociceptive stimuli induce behavioral, autonomic, and hormonal responses in infants similar to those seen in older individuals.

- Chronic or recurrent exposure to nociceptive stimuli can result in sensitization of maturing neuronal pathways, leading to hypersensitivity to pain.

- Clinical Features:

- Facial grimacing.

- Crying.

- Changes in crying pattern.

- Inconsolableness.

- Irritability.

- Changes in sleep pattern.

- Neonatal Pain Assessment:

- Scoring methods for acute & postoperative aches in infants estimate physiological parameters, behavioral modifications, and contextual elements.

- Examples include the Premature Infant Pain Profile (PIPP), Neonatal Infant Pain Scale (NIPS), Neonatal Pain Agitation Sedation Scale (N-PASS), and Crying, Requires Oxygen Saturation, Increased Vital Signs, Expression, Sleeplessness (CRIES) score.

- Management: Neonatal Pain Ladder

- Principles:

- Appropriate analgesia is based on the stages of the WHO analgesic ladder.

- Preemptive analgesia is administered before, during, and after painful procedures.

- Regular examination of the intensity of pain & reaction to analgesia.

- The choice of the step depends on the anticipated intensity of the pain.

- Steps can be combined if single measures aren’t enough.

- Analgesic Steps:

- Step 1: Nonpharmacological measures, such as breastfeeding, pacifier use, skin-to-skin contact, and oral sucrose.

- Step 2: Topical analgesia, for example, topical lidocaine, or tetracaine gel.

- Step 3: Oral, rectal, & IV oversight of acetaminophen/NSAIDs.

- Step 4: IV infusion of opioids.

- Step 5: Subcutaneous infiltration of lidocaine/particular nerve obstructions.

- Step 6: Sedation or general anesthesia.

- Principles:

Effects of Pain Management

Effective pain management encompasses a range of positive outcomes that go beyond just alleviating pain. These effects contribute to an improved overall well-being and quality of life:

- Pain Relief: The primary objective of pain management is to provide relief from discomfort. Effective pain management techniques can significantly reduce or eliminate pain, allowing individuals to experience greater comfort and improved daily functioning.

- Enhanced Mobility: Pain management strategies often include measures to regain range of motion and mobility. This can be particularly beneficial for individuals with musculoskeletal issues or injuries. Increased mobility can lead to improved physical function and independence.

- Stress Reduction: Pain is not only physically taxing but also psychologically stressful. Pain can elevate blood pressure and contribute to a state of distress. Proper pain management helps reduce stress levels associated with pain, promoting overall well-being.

- Gradual Return to Activities: Pain management specialists often advise a gradual return to various activities as part of the treatment plan. This gradual approach to resuming daily activities promotes healing and minimizes discomfort. Patients may notice a significant reduction in pain levels without feeling overwhelmed or uncomfortable.

- Control and Comfort: Pain management techniques provide individuals with a sense of control over their pain. This control is essential for many patients as it empowers them to actively participate in their recovery process. Feeling in control can significantly enhance one’s comfort and confidence.

- Improved Quality of Life: Pain management is a cornerstone of a good quality of life. Managing pain not only reduces physical discomfort but also positively impacts emotional well-being. Pain often involves various components, including cognitive, motivational, affective, behavioral, and physical aspects. Effective pain management can relieve anxiety, and emotional distress, and enhance overall well-being. It enables individuals to regain functional capacity and fulfill their roles in family, social, and vocational settings.

Pain management plays a pivotal role in improving the overall quality of life by addressing both the physical and psychological aspects of pain. It empowers individuals to manage their pain effectively, reduce stress, and regain control over their lives.”

Side Effects of Pain Medications

Common pain medications can have various side effects, including:

- Paracetamol: Side effects are rare when taken at the recommended dose and for a short duration. Paracetamol can potentially cause skin rash and liver damage if used in excessive doses over an extended period.

- Aspirin: The most common side effects include nausea, vomiting, indigestion, and the possibility of stomach ulcers. Some individuals may experience more severe side effects like asthma attacks, tinnitus (ringing in the ears), kidney damage, and bleeding.

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): Potential side effects encompass headache, nausea, stomach upset, heartburn, skin rash, fatigue, dizziness, tinnitus, and elevated blood pressure. NSAIDs can also exacerbate heart failure or kidney issues, and increase the risk of heart attacks, angina, strokes, and bleeding. They should always be used cautiously and for the shortest necessary duration.

Opioid pain medications like morphine, oxycodone, and codeine are commonly associated with side effects such as drowsiness, confusion, falls, nausea, vomiting, and constipation. They can also impair physical coordination and balance. Notably, these medications can lead to dependence and respiratory depression, potentially resulting in accidental fatal overdose.

For a more comprehensive list of side effects, refer to the Consumer Medicine Information leaflet. It’s crucial to consult with your doctor or pharmacist before taking any pain medication to ensure it is safe and suitable for your specific needs.

Precautions When Taking Pain Medications

It’s essential to approach over-the-counter pain medications with caution, much like any other medicine. It’s always advisable to discuss any medications with your doctor or pharmacist.

Here are some general recommendations:

- Avoid Self-Medicating During Pregnancy: Refrain from self-medicating with pain medications while pregnant, as some may pass through the placenta and potentially harm the fetus.

- Be Cautious in Older Age: Exercise caution if you’re elderly or caring for an older individual. Older individuals are at an increased risk of experiencing side effects. For instance, regular aspirin use for chronic pain, such as arthritis, can lead to dangerous bleeding stomach ulcers.

- Consult a Pharmacist: When purchasing over-the-counter pain medications, consult with a pharmacist about any prescription and complementary medications you’re taking. They can help you select a pain medicine that is safe and suitable for your specific situation.

- Avoid Combining Multiple Medications: Refrain from taking more than one over-the-counter medicine simultaneously without consulting your doctor or pharmacist. Accidental overdoses can occur more easily than you might think. For instance, many ‘cold and flu’ remedies contain paracetamol, so it’s crucial not to use any other paracetamol-containing medication concurrently.

- Seek Professional Care for Sports Injuries: If you have a sports injury, it’s essential to seek proper treatment from your doctor or a healthcare professional.

- Don’t Use Pain Medications to ‘Tough It Out‘: Avoid using pain medications as a means to endure discomfort without addressing the underlying issue.

- Consult for Chronic Conditions: Before using any over-the-counter medication, consult your doctor or pharmacist if you have a chronic (ongoing) physical condition, such as heart disease or diabetes.

Conclusion

Chronic pain can be managed through a range of accessible and effective techniques.

The primary goals of pain management are to alleviate chronic pain and enhance an individual’s ability to cope with it.

Certain approaches like acupuncture, physical therapy, and yoga are best pursued under the guidance of trained professionals to ensure safety and effectiveness.

It is crucial for individuals to consult their healthcare provider before starting any new medication. This step ensures that the medication is safe, won’t exacerbate pain, and doesn’t interact negatively with any other drugs the person may be taking.

FAQ

What are the 4 key points in pain management?

Painkillers are among the most important pain management techniques, physical therapies (including massage, hydrotherapy, heat or cold packs, and exercise), psychological treatments (such as meditation, relaxation exercises, and cognitive behavioral therapy), procedures combining the mind and body (like acupuncture), communities of support.

What are the different types of pain management?

Pain Control for Particular Types of Pain:

Treatments for chronic pain include nonopioids, mild opioids, opioids, antidepressants, capsaicin cream, nonpharmacological approaches like bioelectric therapy, and radiation therapy. Short-acting opioids and nonpharmacological remedies like acupuncture or relaxation techniques are effective pain relievers.

What are the 7 parameters of pain?

Physical, sensory, behavioral, social, cognitive, affective, and spiritual are the seven dimensions or main characteristics of pain. You must be able to precisely analyze each dimension and comprehend what it includes in order to conduct a thorough pain evaluation.

What are the 3 types of pain?

There are three different types of musculoskeletal pain: nociplastic, neuropathic, and nociceptive. Nociceptive pain may be brought on by tissue injury or damage. Ankle sprains and contact with a hot stove are two instances of this type of discomfort.

What is the most common treatment for pain?

Typically, the first line of treatment for mild to moderate pain is paracetamol. It could be given for pain due to a skin injury, headache, or disorders that affect the muscles and bones. For the treatment of osteoarthritis and back pain, paracetamol is frequently given.

Reference

- Professional, C. C. M. (n.d.). Pain Management. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/treatments/21514-pain-management

- Pain and pain management – adults. (n.d.). Better Health Channel. https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments/pain-and-pain-management-adults#types-of-pain

- Pope, C. (2023, July 26). Pain Management: Types of Pain and Treatment Options. Drugs.com. https://www.drugs.com/article/pain-management.html

- Zoppi, L. (2020, December 22). 13 ways to manage chronic pain. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/pain-management-techniques#physical-methods

- Non-Drug Pain Management. (n.d.). https://medlineplus.gov/nondrugpainmanagement.html

- Helm, S. (2023, June 27). Pain Management: Types, Guidelines, Treatment, Home Remedies, and Relief. MedicineNet. https://www.medicinenet.com/pain_management/article.htm

- Pain management – Knowledge @ AMBOSS. (n.d.). https://www.amboss.com/us/knowledge/pain-management/

- Image – The Pain Clinic – A Communal Care For Pain. (n.d.). Kauvery Hospital. https://www.kauveryhospital.com/news-events/march-the-pain-clinic-a-communal-care-for-pain-2019

- Pain Management | Conditions & Treatments | UT Southwestern Medical Center. (n.d.). https://utswmed.org/conditions-treatments/pain-management/

20 Comments