FAI Syndrome (Femoroacetabular impingement syndrome)

What is Femoroacetabular impingement syndrome?

Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI), it is also called hip impingement, is a condition where the hip joint is not shaped normally. Painful Femoroacetabular impingement is referred to as Femoroacetabular Impingement Syndrome (FAIS). This causes the bones to painfully rub all together. Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) refers to early contact (impingement) between the bones of the hip during movement, due to a variation in the shape of the bones of the hip joint (femur (thigh bone) and the acetabulum (hip socket)). The pinching or friction may cause damage to the labrum (fibrous cartilage that lines the outer edge of the socket) and/or the articular cartilage (the white covering over the bony surfaces that results in the very smooth surface gliding of the articulation of joint).

This may result in a reduced range of motion (stiffness) and, in a relatively small percentage of people, hip pain associated with extra forces being placed across joint structures such as the acetabular labrum and cartilage. Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) previously also called “acetabular rim syndrome” is an important cause of early osteoarthritis of the hip. This condition can be treated with physical therapy, rest, corticosteroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), physical therapy, rest, and surgery.

Anatomy Of The Hip – What Is Hip Impingement?

To understand better hip impingement, it is important to briefly focus on the anatomy of the hip, specifically the hip joint. The hip joint is a type of ball and socket variety of joints. The acetabulum comprises the “socket” portion of the joint. The outer rim of the acetabulum is made up of fibrocartilage also called the labrum. The labrum extends the ball and socket and increases the overall stability of the hip joint and acts to seal off the joint fluid to help out lubricate the joint. The labrum also allows the ball and socket hip joint to operate it smoothly during movement. The femoral head, and/or the top portion of the thigh bone, creates the “ball” portion of the hip joint. Disease, deformity, injury, and other tissues involving the ball and socket type of hip joint, may lead to a painful condition known as hip impingement. Hip impingement is distinguished by the extra bone around the femoral head and the acetabulum.

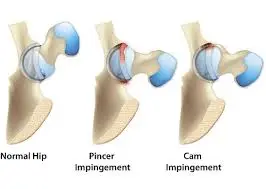

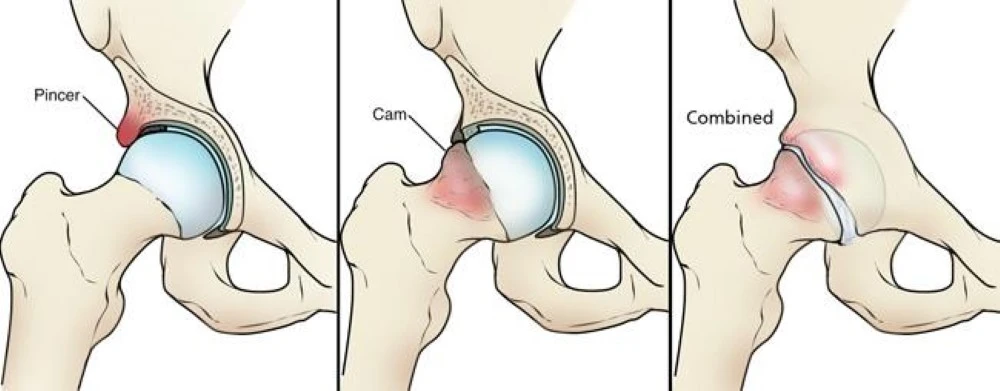

As a result of these growths around the femoral head, the joint is not able to properly glide during movement, limiting the joint is the overall range of motion. There are two main categories of hip impingement: cam impingement and pincer impingement. the Cam type of hip impingement is the result of an abnormally shaped ball portion of the hip joint, leading to friction and resistance within the socket. The pincer type of hip impingement results from an excessive envelopment of the femoral head by the acetabulum, leading to the femoral neck coming into the contact with the acetabular rim during the movement. Over time, this continuous contact may lead to damage to the labrum and surrounding cartilage. It is possible for a patient to exhibit both the cam and the pincer impingement, and this is known as combined hip impingement. A slippery tissue called articular cartilage that covers the surface of the ball and the socket. It creates a smooth, low-friction surface that assists the bones to glide easily across each other during the movement.

The acetabulum is ringed by the strong fibrocartilage known as the labrum. The labrum forms the gasket around the socket, creating a tight seal and helping to provide stability to the joint. Femoroacetabular Impingement – Trauma, acetabular labral impingement, capsular laxity, dysplasia, and degeneration are causative factors for tears in the acetabular labrum leading to the anterior hip or groin pain. There may be associated structural abnormalities in the acetabulum or femur. While many instances of hip impingement are related to the deformities of the joint, another instance may result from recurrent injury and damage to the hip joint and surrounding tissues over time, especially as a result of the participation of the athletes. Due to abnormal contact and wear, the bony protrusions that develop within the joint may lead to damage to the labrum and articular cartilage, leading to a condition known as osteoarthritis.

Description = In Femoroacetabular impingement, bone overgrowth is called bone spurs and it develops around the femoral head and/or along the acetabulum. This extra bone causes abnormal contact between the hip bones and prevents them from moving smoothly during movement. Over time, this can result in the tears of the labrum and the breakdown of articular cartilage (osteoarthritis). Femoroacetabular Impingement – occurs due to Trauma, acetabular labral impingement, capsular laxity, dysplasia, and degeneration these are the causative factors for tears in the acetabular labrum leading to anterior hip or groin pain.

There may be associated structural abnormalities in the acetabulum or femur. the Acetabular labral pathology is associated with hip OA in older patients. 57 Patients usually present with pain that is activity-dependent and described with mechanical symptoms such as clicking, locking, catching, or giving way. the Groin pain is most often related to an anterior tear, and the buttock pain is most often related to a posterior tear. the positive tests typically include pain with the impingement test which indicates the anterior lesion. How long does FAI take to heal – Recuperation time from most FAI surgical procedures is 4 to 6 months to full, unrestricted activity.

Your postoperative activity level will depend on your surgeon’s nomination, the type of surgery performed, and the condition of the hip joint at the time of surgery. What exercises do not have to do with FAI – Avoid exercises comprise significant hip flexion with internal or external rotation as they aggravate the condition. Deep lunges, high jumps, squats, high knees, rowing. leg presses and squat jacks should be avoided. How should someone with a symptomless cam or pincer morphology be managed – Rehabilitation techniques with core and pelvic stability can be recommended. However, it is unknown whether these individuals will progress to femoroacetabular impingement syndrome. How long does FAI take to heal – Recuperation time from most FAI surgical procedures is 4 to 6 months to full, unrestricted activity.

Your postoperative activity level will depend on your surgeon’s nomination, the type of surgery performed, and the condition of the hip joint at the time of surgery. What exercises do not have to do with FAI – Avoid exercises comprise significant hip flexion with internal or external rotation as they aggravate the condition. Deep lunges, high jumps, squats, high knees, rowing. leg presses and squat jacks should be avoided. How should someone with a symptomless cam or pincer morphology be managed – Rehabilitation techniques with core and pelvic stability can be recommended. However, it is unknown whether these individuals will progress to femoroacetabular impingement syndrome.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

The hip (acetabulofemoral joint) is a synovial joint formed between the femur and the acetabulum of the pelvis bone. The head of the femur is covered with Type II collagen (hyaline cartilage) and proteoglycan. The acetabulum is the concave portion of the ball and socket type of hip joint. The acetabulum has a ring of fibrocartilage known as the labrum that deepens the acetabulum and improves the stability of the hip joint.

femoroacetabular impingement is an unevenly shaped hip joint that causes two bones in the hip to rub together. The pressure causes friction between the top of the femur (thighbone) and/or the acetabulum (part of the pelvis). femoroacetabular impingement can limit motion and cause pain. Without treatment, femoroacetabular impingement can lead to damage to the cartilage that provides cushioning in the hip. This damage can lead to arthritis and/or painful joint deterioration. Some people need surgery to restore the damage. How common is femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) – femoroacetabular impingement is a common cause of hip pain in adolescents, adults, and athletes of all ages.

Mechanism of Injury / Pathological Process

femoroacetabular impingement syndrome is associated with three variants in the morphology of the hip joint: cam, pincer, and the combination of the cam and the pincer. These morphologies are thought to be fairly common (around 30% of the general population), including in people without hip symptoms. Raveendran et al. found that 25% of the men and 10% of the women had evidence of cam morphology in at least one hip while 6-7% of the men and 10% of the women demonstrated pincer morphology. Thus, the isolated presence of either the cam or the pincer morphology is insufficient for a diagnosis of femoroacetabular impingement syndrome.

Cam morphology describes a flattening or the convexity of the femoral head and neck junction. The morphology is more frequently seen in young, athletic men. the cam type morphology is where the femoral head is non-spherical and the junction between the head and neck of the femur is thicker than normal. This thickening means that as the hip moves into flexion (knee to chest) or internal rotation (knee turns in) there is less bony clearance between the head and the neck junction and the acetabulum. When the cam area comes in contact with the acetabulum, it is referred to as Cam Impingement or Cam femoroacetabular impingement.

This may result in a restricted range of motion and higher loads than normal being placed on the labrum and the cartilage on the outer edge of the acetabulum. The response and risk of developing a ‘cam-type’ bony shape: High exposure to twisting and bending forces across the femoral neck, Involvement in sports that involve these types of forces – Soccer and football codes, hockey, basketball. Training four or more times or week, Being male – a cam shape is much more common in males.

The Pincer morphology describes “over coverage” of the femoral head by the acetabulum in which the acetabular rim is extended beyond the typical amount, either in one focal area or more generally across the acetabular rim. This morphology is more common in women. pincer type morphology refers to a variation in the shape or orientation of the acetabulum. of the whole femoral head by the acetabulum may occur when the socket is deeper than average(global over coverage) or the edge of the socket may sit lower at the front of the femoral head due to an orientation where the socket faces a little more backward than normal (acetabular retroversion – focal over coverage). Both situations may result in restricted movement as the femur and the acetabulum come together earlier in the range, referred to as Pincer Impingement or Pincer femoroacetabular impingement. The labrum can be put under higher stress.

Cam and pincer morphology can lead to damage to the articular cartilage and the labrum due to impingement between an acetabular rim and the femoral head during movement, which causes the symptoms of femoroacetabular impingement syndrome. The population with a combination of cam and pincer often suffers from a slipped capital femoral epiphysis called the Slipped capital femoral epiphysis. They show varying degrees of hip impingement. An estimated 85% of patients with FAI have this type of mixed morphology, although Raveendran et al. found only 2% of the subjects in their prospective longitudinal cohort study that had mixed morphology (albeit in a primarily middle aged population).

Metabolic analysis of the tissue samples by Chinzei et al. suggested that articular cartilage may be the main site of the inflammation and the degeneration in hips with FAI and that if OA progresses, metabolic activity spreads to the labrum and synovium, and labrum. Given that both variants of morphologies can be present in asymptomatic individuals, Casartelli et al. propose that another factor with the bony structures may be involved with FAI syndrome including Weakness of the deep hip muscles which compromises hip stability and leads to an overload of secondary movers of the hip. The femoral head glides anteriorly into the acetabulum and increases hip joint loading. Repeated loading of the labrum leads to the upregulation of nociceptive receptors in that structure through the production of the neurotransmitters such as substances.

What causes femoroacetabular impingement (FAI)?

The hip joint is a ball and socket joint that attaches the femur to the pelvis bone. the individual with femoroacetabular impingement has an abnormality in the ball (top of the femur) or the socket (groove in the hip bone). The abnormality can causes friction during movement or activity and can damage the surrounding cartilage and labrum (cartilage that lines the hip socket). femoroacetabular impingement is a condition related to alterations in the pattern of bony growth. The Bones continue to grow and/or change shape during childhood and adolescence. Growing bones have cartilaginous growth plates or epiphyses from which the bone grows and extends, before fusing into hard bone as ultimately adulthood is reached.

The growth plates are influenced by the amount and type of physical loads they are exposed to. The most common type of FAI, Cam FAI, is thought to develop to respond in physical activity that places load across the growth plate in the neck of the femur. A high-level load across the growth plate may stimulate the excess bone to be laid down in this area. The abnormalities associated with femoroacetabular impingement are usually present at birth. But they can also develop in life later, especially during the teenage years. Based on the systematic review performed by Chaudhry and Ayeni, The etiology of Femoroacetabular impingement syndrome is likely multifactorial. Further research is required to better understand the development of Femoroacetabular impingement-associated morphologies, but the following factors may be associated with its development.

Intrinsic factors supported by:

Radiological findings of Femoroacetabular impingement associated with morphologies among subjects with affected siblings

High instances of cam-type morphology in men and pincer morphology in the women

Exposure to recurring and often supraphysiologic hip rotation and hip flexion during development in childhood and adolescence (e.g. hockey, basketball, or football). The repeated stress of this type may trigger adaptive remodeling and eventually the development of FAI-associated morphologies and symptoms

History of childhood hip disease (e.g. slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) and Legge Calve Perthes disease) which may have altered the shape of the femoral head

Malunion following femoral neck fractures may have altered the contour of the femoral head/neck Surgical over-correction of conditions such as hip dysplasia may lead to the pincer morphology.

Classification of femoroacetabular impingement

Doctors classify FAI into three categories based on the cause:

Cam: The cam type results from a bony growth to the head of the femur. In a few cases, physical activity may cause this growth to occur. The CAM type FAI is characterized by abnormal anatomy of the proximal femur at the head, and neck junction, in which there is typically an aspherical portion of the femoral head, and neck junction that, with the hip flexion and internal rotation, which results in compression and shear forces to the labrum and acetabular rim, respectively. Over time, the repetitive trauma resulting from a CAM type FAI can lead to labral tears, chondral delamination, and detachment.

Pincer: It is caused by extra bone growth in the hip joint, this growth often happens during a child’s development. the Pincer type FAI is distinguished by abnormal anatomy of the acetabular rim. The cause can be either a focal or more global, over coverage of the acetabulum over the normal anatomic femoral head and neck. As a result, the range of motion is limited when the femoral neck comes into contact with the acetabular labrum, again with hip flexion. The force is subsequently transmitted to the acetabular cartilage and/or labrum. With repeated bouts of micro trauma in this fashion, there is a focal degeneration of the labrum with eventual ossification in a well-described and admitted pattern. Another associated lesion with the pincer type impingement is the contra-coup cartilage lesion of the femoral head. Development of the lesions further compromises the biomechanical forces across the hip, predisposing the hip to progressive, diffuse, degenerative changes over time.

Combined: This type of FAI presents with both CAM type and pincer type deformities with abnormal morphology of both the proximal femur and acetabulum, along with their associated characteristic lesions. Recent reports recommend that this may be the most often pattern of FAI. A physically active person may experience pain from FAI earlier than people who are not as active. But in most cases, exercise does not cause FAI.

Biomechanics Affected by FAI

A handful of studies have recruited different groups of femoroacetabular impingement affected persons and had them perform a range of functional movements to test how these movements were affected by the presence of symptomatic or asymptomatic femoroacetabular impingement.

A systematic review carried out by the Freke et al examined twelve studies and reported that individuals who presented with Femoroacetabular impingement syndrome showed significantly decrease ranges of motion for the abduction of the hip and flexion of the hip. Additionally, six studies showed conflicting however moderate muscular weakness in the hip adductors and the external rotators, as well as restricted evidence for reduced strength in the hip flexors, extensors, and abductors for femoroacetabular impingement, in affected persons.

The review noted that there were no remarkable differences in depth of squat performance and pelvic range of motion between those of the femoroacetabular impingement affected group and/or the control group. More notably, a handful of the studies within the review advised the presence of femoral acetabular impingement negatively affects the ranges of motion in the sagittal and frontal planes while observing gait mechanics supplementary to lower values of peak hip extension, abduction, adduction, and internal rotation.

Additionally, a relevant systematic review and meta-analysis were performed by King and colleagues, which involved 14 studies and measured various biomechanical and functional movements such as gait and squatting. In the examination of gait patterns, a reduced peak hip extension angle during the stance phase was found, with no difference in peak hip flexion angle. Patients who presented with femoroacetabular impingement demonstrated gait with a decreased total ROM in the sagittal plane with no significant differences in either adduction or abduction angles within the frontal plane.

There was, however, a notable reduction in the peak internal rotation angle of the hip in the transverse plane of gait. In the examination of squatting function, individuals with FAI displayed a low degree of squat depth when compared to the control group, however no significant differences with hip flexion angles.

Epidemiology of FAI syndrome

Femoroacetabular impingement is common in active young and middle-aged adult persons, with pincer morphology being more common in middle-aged women and cam morphology more common in young men.

Prevalence of Femoroacetabular Impingement syndrome

Of the two classifications of FAI, the cam is the more common, shown in various research studies. The Copenhagen Osteoarthritis study took a group of 3202 people and discovered that 17% of the men had presented with cam malformation and had reported hip pain, while that number was only 4% of the women. Another study carried out by Hack et al looked at the prevalence of cam type femoroacetabular impingement morphology and demonstrated that cam was present in 25% of men and only 5% of women. Furthermore, a study carried out by Beck et al confirmed the aforementioned numbers and concluded that cam type femoroacetabular impingement was more common in men than women, with an overall general consensus that cam type femoroacetabular impingement was more often than pincer type femoroacetabular impingement. In a systematic review carried out by Mascarenhas et al, the existence of cam and pincer type FAI was examined via the results of radiographic imaging.

This study illustrated that both the presence of cam type morphology and pincer type morphology were significantly more frequent among symptomatically affected patients than among asymptomatic. FAI normally affects patients in their 20s to 40s. The estimated prevalence is 10% to 15%. Nearly 86% have a combination of both cam and pincer impingement. Approx 14% have pure FAI forms of either cam or pincer impingement. Commonly associated with sports such as ice hockey, soccer, ballet/dance/acrobatics, rugby, lacrosse, football, rowing, and golf.

Does FAI lead to hip replacement?

Both hip dysplasia and/or hip impingement (femoroacetabular impingement, or FAI) is, in fact, considerable causes of osteoarthritis in the young adult hip and frequent result in the need for surgical reconstruction and/or replacement of the joint (a procedure called arthroplasty) at a young age.

What aggravates hip impingement?

an individual with hip impingement is frequently reported with anterolateral hip pain. Common aggravating activities include prolonged sitting, leaning forward, getting in or out of a car, and pivoting activities in sports. The use of flexion, adduction, and internal rotation of the supine hip typically increases the pain.

Risk factors of femoroacetabular impingement syndrome

Who is at risk of developing a femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) – In a few cases, people who are physically active have a higher risk of developing FAI syndrome.

- high impact sport activity, mostly in adolescence during physeal closure

- overuse activity

- previous slipped capital femoral epiphysis and/or Perthes disease

- coxa profunda, protrusio acetabuli

- acetabular retroversion

- posttraumatic deformitie

Associated conditions with the femoroacetabular impingement syndrome

- osteoarthritis of the hip

- cam morphology

- pincer morphology

- mixed cam/pincer morphology

- os acetabulum

Location of femoroacetabular impingement

The morphological change in the cam morphology is situated at the femoral head and neck junction, most common in the anterosuperior position lateral to the physeal scar with decreased femoral head and neck offset.

Acetabular over coverage in pincer morphology can be global or focal and concerns the acetabular rim, focal acetabular over coverage can be anywhere but most often is also located anterosuperior due to acetabular retroversion, posterior wall prominence, and os acetabuli being other forms of focal over coverage.

Labral injuries and tears are most often located at the most prominent site of the cam and/or pincer morphology, which is most frequently present at the anterosuperior portion of the acetabular rim. The Chondral contrecoup lesions in the case of pincer morphology are often found posteroinferiorly

What are the symptoms of femoroacetabular impingement (FAI)?

Some people with FAI notice no symptoms. Signs of the condition may appear as damage in the hip worsening. The signs and symptoms of femoroacetabular impingement include Moderate to marked hip and/or groin pain related to certain movements or positions.

- The pain reported in the thigh, back, or buttock

- Restricted hip range of motion

- Clicking and/or catching

- Locking or giving way

- Low back pain

- Pain at the SI (sacroiliac joint on the back of the pelvis), the buttock, or the greater trochanter (side of the hip).

- It is often confused with other sources of pain, such as hip flexor tendinitis, pain from the back (disc or spine), testicular pain, and sports hernia.

- Reduced ability to perform activities of daily living and sports.

- Limping – difficulty in walking, typically because of a damaged or stiff leg or foot.

- Stiffness in the hip

Clinical presentation / clinical findings

- Although, pain from FAI is commonly held to be aggravated with acceleration sports as well as squatting, climbing stairs, and long time sitting. With the femoroacetabular impingement that may have advanced to hip osteoarthritis, the signs and symptoms that are more typical of this condition may be identified.

- Issues with the lower specificity of tests such as the impingement test (FADIR) limit their accuracy and usage as stand-alone tests. As a consequence, false positives, inaccurate diagnoses of Femoroacetabular impingement syndrome, and incorrect treatment may occur. a clinical prediction rule to achieve both higher specificity and sensitivity and thus a more accurate diagnosis in a clinical setting.

- Various pain provocation hip impingement tests are used clinically. The most often used test is flexion adduction internal rotation (FADIR), but it is not specific. The FADIR position of incitement is associated with impingement at the anterior rim of the acetabulum. The Pain associated with the posterior rim can be provoked by passively bringing the hip from flexion to extension while maintaining the position of hip abduction and external rotation with the leg hanging off the table.

- Hip range of motion is often restricted, most commonly through internal rotation with the hip flexed. However, Diamond et al. noted that in some studies, controls were not imaged for asymptomatic femoroacetabular impingement. Thus, caution is needed with generalizing the results and further research will help to clarify the impact of FAI on the hip range of motion.

- a single limb squat can assist to identify hip abductor weakness.

- An increase in pain with hip flexion could indicate FAI or other intra-articular pathology.

- Assessing stair ascending and/or descending as they require greater hip flexion than walking on a flat surface.

- Findings of strength deficits associated with FAI have been reported in the literature (particularly hip flexion and adduction) but as with studies investigating the range of motion and FAI, some controls were not imaged for asymptomatic FAI, so caution is needed with generalizing these results. Further research will assist to clarify the impact of FAI on strength, particularly at functional as opposed to maximal levels of muscle contraction.

- Physical Examination of the Hip = Inspection of hips – Asymmetry suggests SI joint dysfunction or leg-length discrepancy, either of which can cause SI joint pain, pubic symphysis pain, or muscle strain.

- Palpation of bony landmarks and muscles – Tenderness indicates that tissue is involved. Tenderness over the greater trochanter suggests trochanteric bursitis, which can coincide with the intra-articular hip disorder; mass suggests a tumor, Range of motion (flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, internal and external rotation) – assess for pain; localize pain. Pain in a stretched muscle indicates strain; pain in the groin suggests intra-articular hip disorder; pain with slight motion is concerning for septic arthritis. Passive (examiner moves the hip) Active (patient moves) Resisted (examiner resists motion to test muscle strength) = Limitation of motion reflects the severity of the condition; pain helps to localize the source of pain Weakness or pain in muscle suggests strain.

- History- Patients with femoroacetabular impingement typically have anterolateral hip pain. They often cup the anterolateral hip with the thumb and/or forefinger in the shape of a “C,” termed the C-sign. the Pain is sharp when turning and pivoting, mostly toward the affected side. It can be worsened by prolonged sitting, rising from a seat, getting into or out of a car, or leaning forward. Pain is usually gradual and progressive.

How is femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) diagnosed?

Doctors use several tests to diagnose femoroacetabular impingement. Your doctor will ask about the family history and activity levels. To confirm the diagnosis of femoroacetabular impingement, your doctor may use:

Imaging tests: Tests such as X-rays and Magnetic resonance imaging help doctors identify the abnormalities and the signs of damage in the hip joint. the AP x-rays of the pelvis and lateral x-rays of the femoral neck are recommended initially for suspected FAI syndrome. The views can provide general information relating to the hips, as well as specific information related to the cam or pincer morphologies or another potential source of the patient’s pain. Dunn’s lateral view shows the deformity present on the anterolateral side. the Frog leg position shows the deformity present on the anterior side.

The alpha angle is the radiological measurement for the evaluation of the cam morphology. This angle’s horizontal line is drawn from the center of the head of the femur towards the base of the neck of the femur and the vertical line is drawn along the edge of the socket, matching the center of the femur. Most recently a value of ≥ 60° has been proposed as a definition of cam morphology.

The lateral center edge angle (LCEA) measures the femoral head bony coverage by the acetabulum. First, the best-fit circle for the inferior and the medial margins of the femoral head is drawn. Next, the angle between two lines drawn from the center of the circle is measured: one line runs vertically along the longitudinal axis of the pelvis and the other line runs to the lateral acetabular rim. A lateral center edge angle greater than 39 degrees defines pincer-type impingement vs. a lateral center edge angle less than 20 degrees indicate acetabular dysplasia.

X-rays of an A/P pelvic view and the lateral view of the proximal femur

- Cam – The pistol grip deformity — the shape of the proximal femur in this deformity appears like a pistol

- Alpha angle — also can be measured if >55° is indicative of a cam impingement

- Pincer – Crossover or figure-of-eight sign — the posterior rim of the acetabulum does not lie lateral to the anterior wall on an AP view

- Ischial spine sign — ischial spine projects into the pelvis

- Posterior wall sign – the femoral head lies lateral to the posterior wall

- the Coxaprofunda – teardrop crosses over the ilioischial line but the femoral head.

- Protrusioacetabuli — both the teardrop and the femoral head cross the illioischial line.

If further assessment is required (e.g. for better appreciation of 3D morphology of the hip and for associated cartilage or labral lesions), cross-sectional imaging (CT or MR arthrogram) is recommended.

CT Scan

- Osseous morphological abnormalities of the acetabulum and femoral head and neck junction that are possible pincer and/or cam morphology can be easily and fast assessed in multiple planes including radial (double oblique) reconstructions along the femoral neck. In addition to 3D reconstructions which enable surgical planning e.g. for osteo chondroplasty. Typical findings on computerized tomography are an osseous bump in the anterosuperior position of the femoral head and neck junction with cysts and herniation pit as indirect signs for cam morphology. extension in acetabular depth, acetabular ossicle, and acetabular retroversion indicate pincer morphology. Findings can be objectified with the following measurements such as alpha angle: >55° in anterior and >60° in anterosuperior position indicate cam morphology femoral head-neck offset: <6-7 mm in anterosuperior position indicates cam morphology acetabular retroversion: (normal 12-20°) as an indicator for pincer morphology

MRI

- Similar to a CT scan. the MRI allows the assessment of the cam and/or pincer morphology. A 3D sequence of the hip in question can be considered, as easy and fast radial (double oblique) reformations along with the femoral neck and proper evaluation of the acetabulum. In addition to the morphological assessments of the femoral head and neck junction and the acetabulum and measurements as acetabular retroversion, alpha angle, and femoral head and neck offset MRI allows for assessment of concomitant labral and chondral injuries like chondral labral separation or carpet lesion and/or features indicative of the latter e.g. para labral cysts.

Magnetic resonance arthrogram has typically been preferred over MRI because it has shown greater accuracy in identifying the defects in the labrum and cartilage. However, extra recent research suggests that 3T MRI is at least equivalent to 1.5T MRA for detecting these types of defects.

The Impingement test: Your doctor brings your knee up to your chest and rotates it towards the opposite shoulder. Someone with femoroacetabular impingement will feel the same kind of pain with this movement. The (FABER) Flexion abduction external rotation test is performed with the patient in the supine position. The leg is passively flexed at the hip and the knee, abducted and externally rotated until the lateral ankle rests just proximal to the knee on the contralateral extremity. The pelvis is then stabilized and a downward force is applied to the flexed knee, pushing it toward the exam table. the positive test is reported as either reproduction of pain or reduced ROM compared to the non-affected limb.

The (RSLR) resisted straight leg raise test is also performed with a patient in the supine position. The patient actively flexed the straight leg at the hip to 30 to 45 degrees of flexion. They are asked to resist the manual downward force on the leg applied just proximal to the knee. The positive test is reported as recognizable pain and weakness. Although the aforementioned physical tests may assist the tools, Tijssen et al. conclude that these tests are not able to reliably confirm and/or discard the diagnosis of FAI, when viewed in isolation.

The FABER test is performed with a patient in the supine position. The leg is passively flexed at the hip and/or the knee, abducted and/or externally rotated until the lateral ankle rests just proximal to the knee on the contralateral extremity. The pelvis is then stabilized and the downward force is applied to the flexed knee, pushing it toward the exam table. the positive test is reported as either production of pain or decreased ROM compared to the nonaffected limb. Patrick (FABER) test the Groin pain indicates an iliopsoas strain or an intra-articular hip disorder; SI pain indicates SI joint disorder; posterior hip pain suggests posterior hip impingement.

FADIR test – Reproducing the patient’s anterolateral hip pain is consistent with FAI – the Log roll (examiner rolls the supine leg back and forth) – Groin pain suggests an intra-articular disorder; posterior pain suggests posterior muscle strain. Patient hops on the involved leg – Pain can occur with strain, FAI, or other intra-articular disorders, but is concerning for hip stress fracture. Examination of lower back, abdomen, and pelvis – Certain conditions can refer pain to in the hip; check for fever or tachycardia, which suggest septic arthritis.

A Local anesthetic: the doctor identifies FAI by injecting the hip joint with numbing medicine to see if the injection relieves the pain.

Physical exam: A physical evaluation helps your doctor assess your range of motion, muscle strength, and the way you walk to determine if the hip joint works properly.

Differential Diagnosis Of FAI Syndrome

- Acute hip pain red flag conditions include Tumour, Infection, Septic arthritis, Osteomyelitis, Fracture, and Avascular necrosis.

- In athletes, other causes of hip pain comprise inguinal pathology, adductor pathology, and athletic pubalgia

- Some important differential diagnoses are as follows:

- Hip dysplasia

- Lumbar spine pain (lower back pain)

- Sacroiliitis (sacroiliac joint pain/dysfunction, back of pelvis)

- Trochanteric bursitis (outside/lateral hip pain)

- Piriformis syndrome (back of hip pain)

- Psychosomatic pain disorder (stress-related illness)

- Iliopsoas tendinitis/tendonitis/tendinosis (hip flexor inflammation)

- Sports hernia (core muscle injury, abdominal muscle strain)

- Quadriceps hernia/strain

- Hamstring tendinitis/tendinosis

Outcome Measures

- International Hip Outcome Tool (iHOT)

- Hip and Groin Outcome Score (HAGOS)

- Hip Outcome Score (HOS)

- Harris Hip Score (HHS)

- Non-arthritic Hip Score

Early predictions of outcomes – A available literature is insufficient to determine if patients with femoroacetabular impingement syndrome have a greater risk of developing hip OA than patients with isolated cam morphologies, or to predict who will develop hip osteoarthritis, chondral or labral damage. A recent study, however, suggested that there is an increased risk of hip osteoarthritis of up to 10% in young patients with cam impingement morphology who were followed for at least 25 years. Negative predictors of return to the high-level sport after surgery for FAI include presurgical chondral damage, mental health concerns in athletes, increased alpha angles, increased body mass index, duration greater than 2 years, or the presence of a limp.

How can you prevent femoroacetabular impingement (FAI)?

Most cases of FAI cannot be prevented. Promoting the treatment is important to prevent FAI from causing more damage to the hip.

What Does Hip Impingement Feel Like?

FAI usually feels like a sharp pain deep in the groin area and/or in the front of the hip. It worsens with athletic activities, or with long time sitting. As the symptoms progress, the muscles surrounding the hip will fatigue and become very sore.

the Hip impingement symptoms are dependent on the severity of the condition. the common hip impingement symptoms comprise stiffness in the upper thigh, in the hip, and around the groin. Pain in these areas is also common. Range of motion is frequently limited for individuals with hip impingement, and sufferers may have difficulty flexing the hip near or beyond a right angle. It is also typical for hip impingement to become extra pronounced during exercise and activity. the Movements that comprise twisting or squatting which may result in a sharp or radiating pain along the affected area. In lower severe cases of hip impingement, patients often report a dull aching sensation during these motions. Prolonged sitting may also cause hip impingement symptom flare-ups. Femoroacetabular impingement symptoms can also consist of lower back pain, and this pain may be present during inactivity or more pronounced following strenuous activity.

To properly diagnose the presence of hip impingement, and to rule out another potential condition, your doctor will conduct a series of physical tests and may also utilize diagnostic imaging. During the hip impingement test, the doctor will slowly guide a patient’s knee towards his or her chest and then slowly rotate the affected leg inward. If this activity causes pain, it may be indicative of hip impingement. Other imaging tests, such as x-rays and Magnetic resonance imaging, may be used to determine the exact diagnosis. Once the condition has been properly diagnosed, the overseeing medical professional will then advocate appropriate hip impingement treatment options.

At different disease stages

Early: The first line of treatment for femoral acetabular syndrome is medical or rehabilitative. This consists of activity modification, restriction of athletic activity, avoidance of the hip motions that exacerbate symptoms, and NSAID medications. The safety and efficacy of physical therapy warrant a trial before pursuing the surgery. As such, physical therapy should be utilized, although, it is important to note that certain passive range of motion and stretching exercises may actually aggravate symptoms, so therapy should be mainly focused on strengthening and patient education. The goal of treatment is to reduce the mechanical contact between the acetabulum and the femoral neck.

Middle: Intra-articular injection of steroids is disputed due to cartilage toxicity from steroid use. However, imaging-guided intraarticular steroid and local anesthetic injections can confirm intra-articular pathology and relieve symptoms if successful. Since a femoral acetabular impingement happens in an active population, activity modification and refraining from athletics can be difficult. Persistent symptoms require further physical therapy attempts. Intra-articular hyaluronic acid supplementation could potentially improve pain and/or function; although, this is only supported by low-quality evidence and is not currently approved by the majority of insurance plans.

Late: A Surgical intervention can be considered if conservative treatments fail to improve symptoms. the Surgical intervention typically comprises either open surgical dislocation with osteoplasty or arthroscopic techniques. Post-operatively, rehabilitation must take into account weight-bearing restrictions, range of motion restriction, and/or a step-wise progression to activity. At a minimum, pain, loss of motion, muscle strength, and proprioception surrounding the hip should be addressed. Return to the sport after surgical intervention varies greatly and depends on a number of factors. look for timelines for return to sport are difficult to predict as no standard rehabilitation protocol has been published. In a recent meta-analysis return to sport after the surgical intervention was an average return of 7 months

A full Personalised Hip Therapy protocol is as follows:

Core Component –

Patient Education and Advice – Relative rest and lifestyle, the activity of daily living, sports modifications to try to avoid FAI e.g. escapee of deep hip flexion, adduction, and internal rotation

Patient Assessment – Thorough patient history, pain-free passive ROM of the hip, hip impingement testing, and strength of hip flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, internal rotation, and external rotation.

Help with Pain Relief – Anti-inflammatories for 2-4 weeks or simple analgesics if anti-inflammatories don’t help, adhere to a personalized exercise program.

Exercise-Based Hip Programme – Start with muscle control work (pelvis, hip, glutes, abdominals), progressing to non-vigorous stretching (hip external rotation, hip abduction in flexion and extension), and strengthening (gluteal Maximus, short external rotators, gluteal medius, abdominals, lower limb in general).

FAI Surgery — What Is Hip Impingement Surgery?

Hip impingement surgery is a frequent treatment option, and many instances of FAI can be adequately treated using arthroscopy. In fact, the use of arthroscopic femoroacetabular impingement surgery rose by 250 percent between 2007 and 2011 according to a recent study, and for good reason. Arthroscopic procedures offer additional advantages over more invasive open surgical procedures. Compared to open hip impingement surgery, arthroscopic femoroacetabular impingement surgery involves a smaller incision, meaning less scarring and faster recovery times. During hip impingement arthroscopic surgery, a little camera (known as an arthroscope) is inserted through a small incision, to allow the doctor to view the damaged joint internally. Then, during the procedure, the doctor may remove or the trim damaged articular cartilage and damaged portions of the labrum on its own.

Tiny bony protrusions along with the acetabular rim may also be removed during hip impingement arthroscopic surgery. During a recent study published by the British Editorial Society of Bone and/or Joint Surgery, up to 80 percent of patients exhibited good or excellent results after arthroscopic femoroacetabular impingement surgery at the mid-term evaluation. While many instances of hip impingement may be treated arthroscopically, very severe instances of FAI may require open surgery to fully access the damaged tissue and bone abnormalities. In some unique instances, it may be necessary to the reshaping of the ball and the socket portions of the joint for an optimal, smooth glide during movement.

Hip impingement arthroscopic surgery is performed again and again as an outpatient procedure, meaning patients normally return home the same day following surgery. Patients should expect to use crutches to support mobility immediately after FAI hip surgery, and some patients may continue to use these crutches for several weeks following the procedure. Arthroscopic hip impingement surgery recovery time will vary for each patient and/or each instance of femoroacetabular impingement. Many femoroacetabular impingement problems can be treated with arthroscopic surgery. the Arthroscopic procedures are done with minute incisions and thin instruments.

The surgeon uses a little camera, called an arthroscope, to view the inside of the hip. During arthroscopy, your doctor can repair and/or clean out any damage to the labrum and articular cartilage. He or she can correct the femoroacetabular impingement. by trimming the bony rim of the acetabulum and/or also shaving down the bump on the femoral head. Certain severe cases may require an open operation with a larger incision to accomplish this. Future Developments As the results of surgery improve, doctors will probably suggest earlier surgery for FAI. Surgical techniques continue to advance and in the future, computers may be used to support and guide the surgeon in correcting and reshaping the hip. The goals of arthroscopic surgery for femoroacetabular impingement syndrome are to correct the morphological changes and address the underlying soft tissue injuries to achieve the impingement in free range of motion and relieve pain. whereas, most patients will make a full recovery in four to six months.

Multiple instances of femoroacetabular impingement can be adequately managed with a personalized approach to conservative care treatment. although, arthroscopic procedures are becoming more popular with competitive athletes and active adults. At Sports Medicine Oregon, we specialize in both the latest conservative care treatment options and/or the latest arthroscopic surgical techniques to treat hip impingement. If you or a loved one are being held back by the pain and discomfort related to hip impingement, come in for a consultation to learn detail about the latest treatment options. Our team is dedicated to assisting patients to achieve their active lifestyle goals without limitations.

What are the treatments for femoroacetabular impingement (FAI)?

FAI treatment varies according to the person and/or the severity of the damage. Treatment options for FAI include:

- Corticosteroids: These drugs decrease inflammation (swelling) in and around the hip joint. Doctors usually deliver treatment by injection.

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): This type of medicine decrease inflammation and is typically taken in pill form.

- Physical therapy: a Special exercise can help strengthen the joint and improve mobility.

- Rest: By limiting the activity, you can reduce friction in the hip joint.

- Surgery: the Doctors repair the joint with operations including:

- Arthroscopic hip surgery: In this minimally invasive procedure is done, a doctor repairs and/or removes damaged bone or cartilage.

- Traditional hip surgery: In more severe cases, doctors make a larger incision in an open operation to repair the damage

Hip Impingement Treatment — Conservative Care Options

Today, there are more surgical and nonsurgical hip impingement treatments to discuss with your doctor. In a few instances of FAI, individuals can minimize pain, stiffness, and discomfort by making basic lifestyle adjustments. For example, those who experience symptom flare-ups after rigorous activity may need to decrease the frequency and intensity of these activities. For less severe instances of hip impingement, nonsurgical conservative care treatment may adequately relife a patient’s FAI symptoms.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (also known as NSAIDs) may be used to assist relieve minor aches and pains. Similarly, the RICE method may also be recommended to assist alleviate hip impingement symptoms. The RICE method is a commonly used treatment for many conditions consist inflammation and pain, especially for individuals who experience flare-ups following rigorous activity. Proper use of ice and/or heat therapy can also relax the surrounding tissues and minimize stiffness. Fortunately, we have curated a comprehensive guide on when to use ice or heat therapy for a range of conditions.

In the conservation treatment- By improving the neuromuscular function of the hip should be a goal of conservative protocols for FAI syndrome due to the weakness of deep hip musculature and an expected subsequent reduction in dynamic stability of the hip joint. Hip-specific and functional lower limb strengthening: deep hip external rotators, abductors, and flexors in the transverse, frontal and sagittal planes for improvement of dynamic stability. Core stability. Postural balance exercises.

Phase-wise Conservative Management for FAI / Guidelines for Manual Therapy & Exercise

ACUTE PHASE I : 0-4 WEEKS

GOALS

· Patient education re: rest, NSAIDs, activity/Activity of daily living modification to adapt to hip morphology, reduce compression and painful movements, cessation of sports or other aggravating factors · Address hip range of motion deficits if any · Stretching structures abound hip complex i.e. muscles, capsule (if needed and if pain-free) · Address motor control deficits around lumbopelvic hip complex · Strengthening weak key muscle groups · Baseline proprioception and effective weight transfer without compensatory movement patterns.

EXERCISE SUGGESTIONS ROM & Flexibility

· Stretches/ROM: – Hip extension / anterior capsule, – Hip flexion, Adduction, and Abductors – Internal rotation at 0° and in flexion positions, ER · Quadruped rocking for hip flexion (pain-free, ensure neutral spine) · Stationary bike high seat avoid deep hip flexion (pain) · Distraction: manual belt assists in restricted ROM. only indicted if loss of motion in a specific range

Muscle Strength & Endurance

Lumbo-Pelvic (core stability): · Supine Transverse abdominis and Pelvic floor setting. cueing should be specific to lifting the pelvic floor and indrawing lower abdominal (effort scale for pelvic floor/abdominal contraction should be 2-4 out of 10 with normal breathing) · Basic supine Transverse abdominis and pelvic floor: · Inner range bent knee fallouts full range · heel march, march (active hip flexion) · heel slides, heel slides + hip flexion (assisted with a belt under femur active) · single leg heel taps as tolerated · Requires activation of Transverse abdominis and pelvic floor to maintain centralization of the femoral head with lower extremity exercise · Standing, sitting, walking, and weight-bearing postures with Transverse abdominis and pelvic floor.

Hip, Gluteals, Hamstrings, Quadriceps: · Prone hip extension off the edge of bed · Clam shells isometric side lying hip abduction /isotonic hip abduction · Supine bridging: double, single, on ball · Standing hip extension, abduction progress to pulleys or ankle weights (do not allow trunk shift) · one leg as tolerated · Squats: wall, mini, progress to deeper squats as able

Proprioception:

2 legs:

· Equal weight bearing: forward/backward and side-to-sideàprogress to single leg weight shift with core activation and hip/pelvic control · Wobble boards with support: side-to-side, forward/backward· Standing on ½ foam roller: balance rocking forward/backward

SUB-ACUTE PHASE II: 4-12 + WEEKS

GOALS · Continue flexibility exercises in pain-free ranges if required · Progress exercises to include more challenges to lumbopelvic hip control (core stability) · Strengthen weak key muscle groups with functional closed chain exercises · Progress proprioception to single leg unaccompanied by compensatory movement patterns

EXERCISE SUGGESTIONS

ROM & Flexibility

· Quadruped rocking with Internal Rotation and External Rotation bias · Stationary bike Elliptical forward (with TA/pelvic floor setting)/backward Stairmaster with Transverse abdominis and pelvic floor setting and adequate pelvic/hip control (i.e. absent Trendelenburg, pelvic rotation) · Treadmill: walk forward and backward (for hip extension), side stepping, interval jog, interval runàrun (if tolerated)

Muscle Strength & Endurance

Lumbo-Pelvic (core stability) + Gluteals, Hamstrings, Quadriceps: · Advanced core: side plank (on elbows/feet), prone plank (on elbows/toes) · Continue hip strengthening with increased weights/tubing resistance · Hip Internal Rotation/External Rotation with pulleys theraband in flexed, neutral, extended positions · Hamstring curls, eccentrics, deadlifts 2à1 leg · Quadruped – alternate arm & leg lift · Shuttle work on strength & endurance, 1 leg (progress with increased resistance) · Shuttle side lying leg press (top leg) · Shuttle standing kick backs (hip/knee extension) · Sit to stand: higher seat, lower seat, 2 legs, single leg · Single leg stance (affected side), hip abduction and extension (unaffected side) · Single leg stance with hip hike ·Sahrman single leg wall glut med (both sides) + mini squat · Tubing kickbacks, mule kicks (both sides) · Lunge: static ¼ – ½ range, full range · Lunge walking, forwards and backwards, hand weights · Side stepping,shuffling,hopping +/- theraband (thigh and ankle) ·Profitter: abduction, extension, side to side · Single leg: wall squating, mini squat, dead lifting · Forward and lateral step-ups 4-6-8″ (push body weight up through weight bearing heel slow or with control, also watch for hip hiking and/or excessive ankle dorsiflexion) · Eccentric lateral step down on 2-4-6″ step with control (watch for the hip hiking or excessive ankle dorsiflexion)

Proprioception :

2 legs – 1 leg:

· Wobble boards: without support: side to side, forward or backward vision, vision removed, 2 legs, · Wobble boards: single leg: side to side, forward/backward · Standing on ½ foam roller: balance rocking forward/backward · Single leg stance 5-30-60 seconds (when full WB without Trendelenburg or pelvic rotation) 5 · Single leg stance 5-30-60 seconds on the unstable surface i.e. pillow, mini-tramp, BOSUÔ, AirexÔ, Dynadisc with or without support – progress to no vision · Single leg stance performing higher end upper body skills specific to the patient goal(s).

Functional Exercises – In progression

Supine bridging: double, single, ball in phase 1

clam shells, long lever hip abduction in phase 1

Quadruped (neutral spine) rocking, Internal Rotation, and External Rotation bias in phases 1 and 2

Squats: wall, mini, 60°-90° in phases 1 and 2

Sit to stand: the high seat, low seat, 2 legs, single leg in phases 1 and 2

Side-step ankle band, shuffling, hopping in phase 2

Lunges: ¼-½-full, forward, backward, walking, hand weights in phase 2

Single Leg stance, + hip hike in phase 2

Step ups 4-6-8 forward, lateral, and/or Step Downs 4-6-8 in phase 2

Single leg: wall squat, mini-squat, deadlift in phase 2

Shuttle standing kickbacks (hip and knee extension) in phase 2

For Proprioception

Wobble boards, ½ foam roller, double, single leg in phases 1 and 2

Squats, Lunges on Dynadisc, Airex, Bosu in phase 2

Single leg balance, then increase time, the complexity of skill in phase 2

For Cardiovascular Fitness

Treadmill: forward, backward, jog, run in phase 2

The general program could consist of manual therapy, motor control exercises, and mobility/stretching exercises as follows:

Manual therapy –

Hip Extension in Standing Mobilisation with Movement (MWM). Motor control exercise – Reverse Lunge with Front Ball Tap. Mobility exercises – Kneeling Internal Rotation Self-Mobilisation with Lateral Distraction.

Hip Distraction during Internal Rotation MWM. Motor control exercise – Isolateral Romanian Deadlift with Dowel. Mobility exercises – Half-Kneel FABER Self-Mobilisation.

Loaded Lateral Hip Distraction MWM. Motor control exercise – Lateral Step-Down with Heel Hover. Mobility exercises – Quadruped Rock Self-Mobilisation with Lateral Distraction

Loaded Internal Rotation. Motor control exercise – Side Plank. Mobility exercises – Prone Self-Mobilisation

Lateral Glide in External Rotation. Motor control exercise – Seated Isometric Hip Flexion. Mobility exercises – ITB Soft Tissue Self-Mobilisation on Foam Roll.

Long Axis Hip Distraction. Motor control exercise – Supine Hip Flexion with Theraband. Mobility exercises – Quadriceps Soft Tissue Self-Mobilisation on Foam Roll.

Orthotics – Custom orthotics as an alternative to the treatment of biomechanical abnormalities by a physiotherapist

Taping – To assist with postural modification e.g. tape thigh into external rotation and/or abduction.

Hip joint injection – For patients who do not improve with the core treatment components above. therapeutic musculoskeletal injections are an advantage for FAI syndrome, but evidence for them is limited. Fashion is a pragmatic, multicentre, assessor-blinded randomized controlled trial, done at 23 National Health Service hospitals in the UK, For the purposes of the FASHIoN trial, a maximum of one steroid injection could be comprised. There is a limited benefit of hip intra-articular corticosteroid injection for the treatment of FAI syndrome.

Bracing – the immediate and longer-term effects of wearing a brace. The brace did modify the kinematics of patients with FAI by limiting movements that were associated with hip impingement (flexion, internal rotation, and adduction of the hip) during frequent activities (squat, stair climbing, and stair descending). The brace didn’t change the kinematics which consisted of the single limb squat. The identified kinematic changes did not lead to reduced pain or improvement in patient-reported outcomes either immediately or after four weeks of daily brace use.

Other Exercises for Gluteal Med and Gluteal Max Muscles

Clam Shell, Side-lying Hip Abduction, Plank (on elbows/toes), Quadruped Opp Arm & Leg, Bridge, 1 Legged Bridge, Side bridge (on elbows/feet), Standing Hip Abduction (Nonweight bearing side), Standing Hip abduction ( weight bearing leg), Side lunge, Forward Lunge, Forward Hop, Sideways Hop, Side Step with Ankle Band, Lateral Step Up, Forward Step Up, 1 Leg Wall squat, Single Leg Squat, Single Limb Dead Lift, Pelvic Drop, Walking, Elliptical.

Hip impingement physical therapy is a frequent option for many patients. Femoroacetabular impingement hip exercises comprise resistance training, to strengthen the abdominal muscles and/or the surrounding tissues of the hip joint. Other FAI exercises focus on balance training, and still, other hip impingement exercises emphasize flexibility and/or increasing the range of motion in the affected joint.

At first, your physical therapist will advise you through the proper technique for each of these hip impingement exercises and establish optimal set and/or repetition parameters to follow, although these set and repetition goals may improve as physical therapy progresses. Once the patient has learned how to properly execute the hip impingement exercises, the physical therapist will design a personalized treatment regimen. Then, a person can perform these FAI hip exercises in the convenience of their own homes. Hip impingement physical therapy is designed to reduce stress on the hip joint, labrum, and surrounding tissues. Many people will begin to notice results after two to three weeks, although it is not uncommon for hip impingement physical therapy to require up to six weeks to produce noticeable positive results.

Top Exercises to Help with Hip Impingement!

Deep squatting.

Kicking.

Getting in and/or out of a low car.

Running drills with high knees.

Putting on shoes, socks, or tying shoe laces.

If the aforementioned treatment options have failed to adequately relieve a patient’s hip impingement, the doctor may recommend hip impingement surgery. Additionally, many people — especially athletes and active older adults — may not want to limit themselves with activity-reducing lifestyle adjustments and may instead choose to undergo hip impingement surgery.

Surgery with a Post-Operative Physiotherapy Programme

A physiotherapist-prescribed rehabilitation program following arthroscopy was found to improve primary outcomes (International Hip Outcome Tool and sport subscale of the Hip Outcome Scale) to a clinically-relevant degree at 14 weeks post-surgery compared to a control group who followed a self-management program with general guidance from their surgeon. In a similar study, the results at 24 weeks were inconclusive due to the less sample size. Physical conclusions were not evaluated in this study.

Subjects in the physiotherapy treatment group attended one pre-operative and/or six post-operative 30-minute sessions with a physiotherapist.

The post-operative visits were two weeks apart on average 12 weeks patient will recover.

Treatment during these sessions consisted of education, manual therapy (mandatory release of key trigger points, optional lumbar mobilization), and, starting at 6 to 8 weeks post-surgery, functional and sport-specific drills.

Training within the patient’s normal sports environment started at 10 to 12 weeks post-surgery.

In addition, these patients performed a daily home exercise program (see exercise sheet below) and an unsupervised gym and aquatic program (pool walking, stationary bike, cross-trainer, and eventually swimming and lower body resistance) at least twice per week.

The full surgical treatment protocol

Manual therapy

Mandatory technique: Trigger point massage of rectus femoris, add Tensor fascia lata/gluteal medius/gluteal minimus and pectineus muscles and fascia. Aim – Address soft tissue restrictions with aim of reducing pain and improving hip range of movement. Description – Sustained pressure trigger point release with muscle on stretch. In general, mobilize restrictions laterally to the line of tension of the muscle being treated. Time frame – Sessions 2–7. Dosage – 30 to 60 s per trigger point.

Optional therapy

Deep hip rotator muscle retraining. Aim – Optimise hip neuromuscular control and improve the dynamic stability of the hip. Description – Seven stages progressing through prone, four-point-kneel, and dynamic standing positions, with and without resistance. Time frame – Pre-op to session 7.Doasage – 1 min, 3 to 6 times per day

Anterior hip stretch. Aim – Assist in regaining full hip extension range of movement. Description – Supine in modified Thomas Test position with an affected leg over the side of the bed. The hip is extended until a stretch is felt at front of the hip. Time frame – Sessions 2–4. Dosage – 5 min daily

Hip flexion and extension in four-point kneel—’ pendulum’ exercise. Aim – Prevent adhesions, especially in those with labral repair. Description – Four-point kneel with the gentle pendular swing of the affected leg into hip flexion and extension as far as comfortable. Time frame – Sessions 2–5. Dosage – 1 min daily.

Posterior capsule stretch. Aim – Assist in regaining full hip range of movement. Description – Lying on the unaffected side with affected hip as close to 90° flexion as comfortable and affected leg over the bedside. Time frame – Sessions 3–7 (sessions 4–7 if microfracture). Dosage – 3×30 sec.

Gym and aquatic program

Stationary cycling.aim – Improve hip range of motion. Description – Upright bike with a high seat to avoid hip flexion past 90°. Initially 15 mins at mod intensity. Time frame – Session 2 onwards (session 3 if microfracture). Dosage – 2 x weekly

Walking in the pool. Aim- Maintain cardiovascular fitness and improve hip range of motion. Description – Walking at chest depth, forwards, straight lines only. 10 mins for FOC and labral repair, 5 mins for Microfracture and ligamentum teres repair. Time frame – Session two onwards (Session three if microfracture). Dosage – two x weekly

Swimming. Aim – Maintain/regain cardiovascular fitness. Description – No kicking until 6 to 8 weeks post-surgery, 500 m to 1 km. time frame – Session 2 onwards (session 3 if microfracture). Dosage – 2 x weekly

Cross trainer. Aim – Maintain/regain cardiovascular fitness. Description – Initially 5 mins at moderate intensity.Time frame – Session 2 onwards (session 3 if microfracture). Dosage – 2 x weekly

Squats, lunges, leg presses, leg extensions Hamstring curls. Aim – To improve lower limb strength and function. Description – Three sets of 10 repetitions, working at ‘moderately hard on the modified rating of perceived exertion. Time frame – Session 6 onwards. Dosage – 2 x weekly

Functional Program

Jogging. Aim – Maintain/regain cardiovascular fitness. Description – jogging on a running track or grass, with an affected leg to the outside of the track, that is, anticlockwise for the right hip. One lap of the oval should be approximately 400 m. time frame – Session 4 onwards (FOC only) session 5 others. Dosage – 3 x weekly 6 laps in the first week, 8 in the second, 10 in the third week (up to 4 km)

Acceleration/change of direction drills. Aim -Improve lower limb strength and function. Description – Zig-zag jogging. Time frame – Session 5 onwards (FOC only)

Session 6 others. Dosage – Dependent on sports goals and surgical procedure.

Sport-specific drills. Aim – Improve lower limb strength and function. Description – Examples: foot drills/serving practice (tennis); corner hit-outs/tackling drills (grass hockey); kicking/marking drills (Australian rules football). Time frame – Session 4 onwards (FOC only) sessions 6 to 7 others. Dosage – Dependent on sports goals and surgical procedure.

The Home exercise

Femoral Acetabular Impingement Rehabilitation (FAIR)

Level 1 – Deep hip rotators lying and facing downs

Starting position – Lie on your stomach with your knees apart. fold your knees so that they are at 90 degrees. Place the sole of the foot on your non-operated leg as opposed to the inner surface of your ankle on your operated side.

Exercise – Keeping your thigh on the bed, gently press the ankle on your operated side against the sole of the other foot. Relax hamstrings. Relax buttock muscles. Breathe. Place your fingers on the bony part of your bottom known as the ischial tuberosity. Then move your fingers 2 cm out and then up. Feel a gentle contraction of the quadriceps femoris muscle underneath your fingers. Hold for 3 sec and then relax for 2 sec (approximately 12 repetitions in one minute)

Dosage – Pre-surgery: 1 minute at least repeat 6 times per day, After surgery: 1 minute, then repeat 3 to 4 times per day

Indication for progression – When able to do 12 contractions in one minute with good technique.

Level 2 – Deep hip rotators on all the fours

Starting position – 4 points kneeling with the lower back in a neutral position.

Exercise – Relax hamstrings. Relax buttock muscles. Breathe. Place your fingers on the bony part of your bottom known as the ischial tuberosity. Move your fingers 2 cm out and then 2 cm up. Feel a gentle contraction of the quadriceps femoris muscle underneath your fingers. Hold for 3 sec and then relax for 2 seconds. It may assist to think of pulling your thigh up towards your pelvis.

Dosage – Pre-surgery: 1 minute, at least 6 times per day After surgery: 1 minute, 3 to 4 times per day Indicators for progression When able to do 12 contractions in one minute with good technique

Variations: If shoulder pain or fatigue is a problem, support your chest on the seat of a chair.

Level 3 – Deep hip rotators on hands and knees along with hip external rotation (twisting foot inwards)

Starting position – 4 points kneeling with the lower back in a neutral position. The affected leg should be parallel to the opposite side, in a relaxed position (ie not twisted inward or outward)

Exercise – Activate the QF muscle, and then gently rotate the foot on the operated leg inwards. Aim for your foot to be above your calf on your non-affected side at the end of the movement. Slowly return to the starting position. Continue to hold the quadratus femoris contraction whilst performing a total of 5 repetitions of the movement. Rest for 3 seconds and then repeat, for one minute continuous.

Dosage – One minute, and then repeat 3-4 times per day

Indicators for progression – When able to perform the exercise for one minute maintaining good technique and with no pain.

Level 4 – Deep hip rotators in four-point kneeling along with hip internal rotation (twisting foot outwards)

Starting position – four points kneeling with the lower back in a neutral position. The affected leg should be parallel to the opposite side, in a relaxed position (ie not twisted inward or outward) Relax hamstrings. Relax gluteals. Continue to breathe throughout the exercise.

Exercise – Activate QF muscle on the affected side. Keep the muscle tightened while you gently rotate the foot on the affected leg outwards. Take the foot as far as you can go comfortably. Slowly return to the starting position. Continue to hold the QF contraction while performing a total of 5 repetitions of the movement. Rest for 3 seconds and then repeat, continuing for one minute.

Dosage – 5 reps then rest and repeat for one minute

Indicators for progression – When able to perform the exercise for one minute maintaining good technique and with no pain.

Level 5, Exercise 1 – Hip external rotation on hands and knees along with resistance band (Theraband )

Starting position Kneeling on all fours with your lower back in a neutral position. Your affected leg should be parallel to the opposite leg, in a relaxed position (ie not twisted inward or outward). Place a resistance band around your ankle on your operated side as shown. Exercise Activates the QF muscle on your operated side. Gently twist your leg to take your foot on the affected side inwards against the pull of the elastic band. Aim for your foot to be above your calf on your non-affected side at the end of the movement. Slowly return to the starting position, and carefully control the speed of the movement. Rest for 3 seconds and then repeat, continuing this process for one minute. Dosage One minute, 3-4 times per day Indicators for progression Able to perform an exercise for one minute pain-free; able to maintain good technique, with smooth, controlled movement.

Level 5, Exercise 2 – Hip internal rotation on hands and knees along with resistance band (Theraband ) Starting position Kneeling on all fours with your lower back in a neutral position. Your affected leg should be parallel to the opposite leg, in a relaxed position (ie not twisted inward or outward). Place the resistance band surrounding your ankle on your operated side as shown. Exercise Activates the QF muscle on your operated side. Keep the muscle tightened. Gently twist your leg to take your foot outwards, away from your other leg, against the pull of the elastic band. Take your foot as long as you can go comfortably. Slowly return to the starting position, and carefully control the speed of the movement. Rest for 3 seconds and then repeat, continuing this process for one minute. Dosage One minute, 3 to 4 times per day Indicators for progression Able to perform the exercise for one minute pain-free; able to maintain good technique, with smooth, controlled movement

Level 6, Exercise 1 – Hip external rotation along with resistance (Theraband ) and abduction with the belt on hands and knees. Starting position Kneeling, on all fours with your lower back in a neutral position and your knees about two fist-widths apart. Place a Pilates belt and/or resistance band surrounding both your thighs and a resistance band around your ankle on your operated side as shown. Exercise Keep your knee on the bed. Tighten the muscle at the side of your hip by pushing your affected side against the belt (as though trying to take your knees apart). At a similar time, activate the QF muscle on your affected side. Gently twist your leg to take your foot inwards as opposed to the pull of the elastic band. Aim for your foot to be above your calf on your non-affected side at the end of the movement. Slowly return to the starting position, and carefully control the speed of the movement. Rest for 3 seconds and then repeat, continuing this process for one minute. Dosage One minute, 3-4 times per day Indicators for progression Able to perform an exercise for one minute pain-free; able to maintain good technique, with smooth, controlled movement.

Level 6, Exercise 2 – Hip internal rotation along with resistance (Theraband®) and abduction with belt in four-point kneeling Starting position Kneel on all fours with your lower back in a neutral position and your knees comfortably apart. Place a Pilates belt and resistance band around both your thighs and a resistance band around your ankle on your operated side as shown. Exercise Keep your knee on the floor. Tighten the muscle at the side of your hip by pushing your affected side against the belt (as though trying to take your knees apart). Activate the quadratus femoris muscle on your operated side. Gently twist your leg to take your foot outwards, away from your other leg, against the pull of the elastic band. Take your foot as long as you can go comfortably. Slowly return to the starting position, and carefully control the speed of the movement. Rest for 3 seconds and then repeat, continuing this process for one minute. Dosage One minute, 3 to 4 times per day Indicators for progression Able to perform an exercise for one minute pain-free; able to maintain good technique, with smooth, controlled movement.

Level 7, Exercise 1 – Arabesque Starting position Standing along with feet shoulder-width apart. Exercise Tense the QF muscle on your operated side. Lean your chest forward and take your arms out to the sides as you lift the non-operated side behind you. Hold the position for 3 seconds. Bring your non-operated leg down to take a step forward. Step forward into your operated side and repeat. Dosage Do as many repetitions as you are able to with good technique and no pain. Aim to do 26 repetitions continuously. You may break this up in the initial stages, for example, 5 arabesques, 5 times per day. Indicators for progression Able to complete 26 repetitions in a row with good technique, and no pain.

Level 7, Exercise 2 – Duck Walk Starting position Have your feet shoulder-width apart. Place a Pilates belt (or another belt) around your thighs, just above your knees. It is best to use a belt rather than an exercise band for this exercise. Do a ¼ squat, so that your knees are bent to around 30 degrees. the knees should be over your big toes. Place your fingers on your quadratus femoris muscle to check for improved contraction. Exercise Keep your ¼ squat position as you walk forward 10 meters. Keep your QF tense during the exercise. Dosage Do one walk of 10 meters, 10 times per day. Indicators for progression Able to complete a 10-meter walk, with good technique and no pain.

Back of hip (posterior capsule) stretch Starting position Lie on your non-operated side. Place a rolled towel near the edge of the bed as shown in the picture. Exercise Bend your affected hip up as close to a right angle as is comfortable. fold your hip forward and drop your knee over the edge of the bed. Dosage Take the stretch to the point of tension (not pain) and hold for 30 seconds. Do this three times. Indication for progression Continues this exercise daily until the external rotation movement (dropping your knee out to the side when lying on your back) is equal to your non-affected hip.

Front of the hip (anterior capsule) stretch Starting position Lying on your back on a bed. Bend up your non-operated leg. Your bottom should be near the edge of the bed on your operated side. Exercise Take your operated leg out to the side and allow it to drop over the edge of the bed. Your thigh should still be supported by the bed. You should feel a stretching in the front of your hip. Dosage – 5 minutes in the morning, every day. Indicators for progression This exercise should be performed daily from two weeks after surgery until six weeks after surgery

Pendulum hip exercises in four-point kneeling Starting position Kneel on all fours with your lower back in a comfortable, neutral position and your head/neck comfortably relaxed. Exercise Shift most of your weight onto your hands and your non-operated knee. Only a minute weight should go through your operated side. Gently slide the knee on your operated side along the bed or floor towards your hands as long as comfortable. Then slide it back down the bed as long as comfortable. Imagine that your leg is hanging and slowly swinging back and/or forth like a pendulum. Dosage Smooth and slow repetitions for one-minute Indicators for progression Once you have full pain-free movement of hip flexion (bringing your knee up towards your chest) you may stop including this exercise in your program. Sample of hip internal rotation exercise from a patient handout provided by Bennell et al (2014)

Complication Of FAI Syndrome

Potential complications from surgical management include the following:

- Neuropraxia, Chrondral injury, Labralinjury, Heterotopic ossification,

- Compression injuries e.g. pudendal nerve, scrotum, labia major

- Injury to the femoral head, Adhesion, Infection, Deep vein thrombosis (DVT), Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), Perineal skin damage, Vascular injury (hematoma), Muscle pain, Incomplete reshaping, Femoral neck fracture, Hip instability, Iliopsoas tendinitis, Avascular necrosis of femoral head, Ankle pain, Bursitis

some Surgical complications are recommended areas of future research to help inform the clinical decision making process. Which are the complications associated with femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) – Some people with FAI who do not receive treatment develop hip osteoarthritis (breakdown of the cartilage around the hip). The complication can lead to severe pain and limited mobility.

Prognosis