Humerus Bone

Description

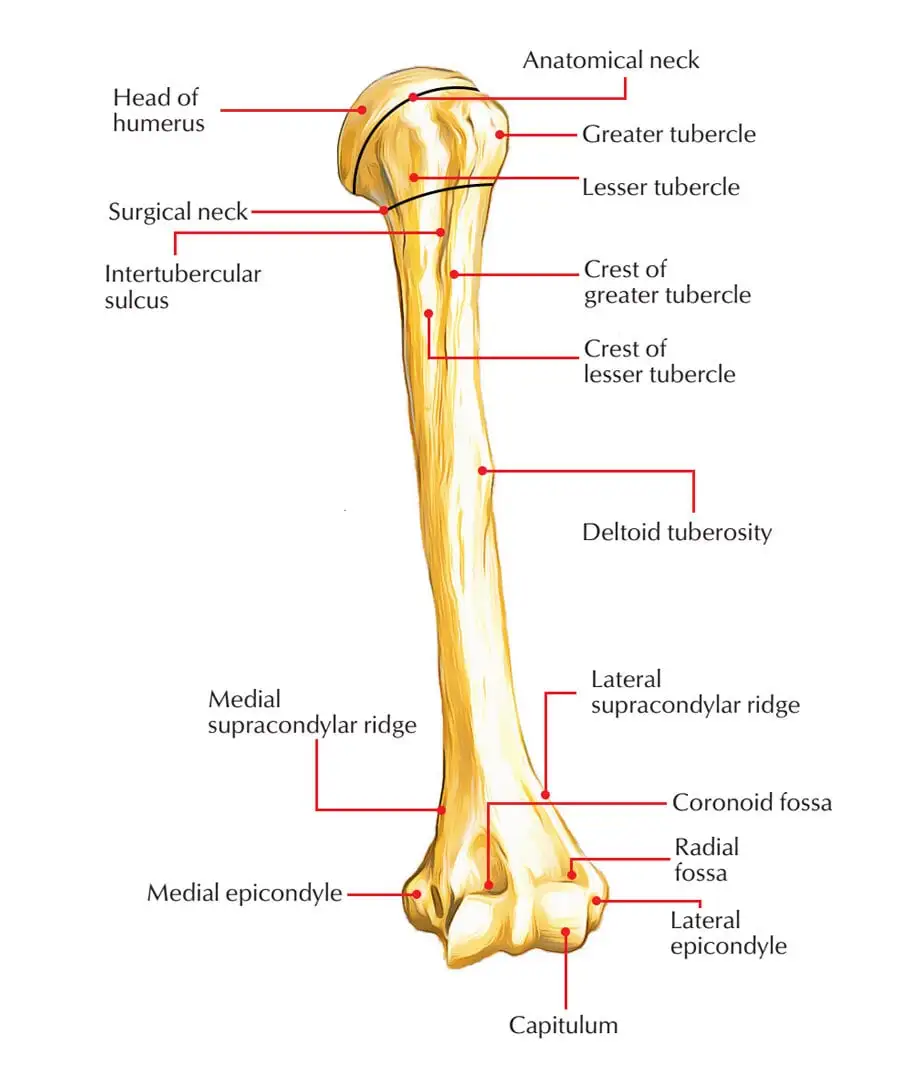

The humerus bone is a long bone that is made up of two extremities (epiphysis) and a shaft (diaphysis). It is the longest bone in the upper extremity.

The humerus is the name of the long bone of the upper arm. Given that it is one of the body’s longest bones, fractures from impacts are more likely to occur. The Latin term for the upper arm is where the word “humerus” originated.

Introduction

The humerus is a key component in the complex dance of movements of the upper limb because of its unique structure, which includes a head, anatomical neck, surgical neck, tuberosities, and body.

Understanding the subtleties of humerus anatomy as a physiotherapist who is committed to patient well-being creates a wealth of opportunities for supportive and productive intervention.

The upper arm bone is called the humerus. It facilitates arm movement and is linked to thirteen muscles. It’s possible that your injured humerus will also harm the muscles and nerves that are connected to it.

You may not even be aware of your increased risk of fractures if osteoporosis weakens your bones.

It is divided into three sections and joins the scapula to the ulna and radius, the two lower arm bones. Two short processes, a narrow neck, and a rounded head make up the humeral upper extremity.

The upper part of the body is cylindrical, while the lower part is more prismatic. There are two epicondyles, two processes, and three fossae in the lower extremity.

The largest bone in the upper extremities, the humerus, defines the human brachium, or arm.

It articulates proximally with the glenoid through the glenohumeral (GH) joint and distally with the radius and ulna at the elbow joint. The most proximal portion of the humerus is the head, which forms a ball and socket connection with the glenoid cavity on the scapula.

Directly behind the humeral head is the anatomical neck of the humerus, which divides it from the larger and lesser tubercles.

What is the humerus bone?

The upper arm bone is called the humerus. It’s the longest bone in your body, excluding the bones in your leg. It’s essential to your arm’s range of motion.

Numerous vital muscles, tendons, ligaments, and sections of your circulatory system are also supported by your humerus.

Your humerus may need to be surgically repaired, and you may also require physical therapy to help you regain your strength and range of motion.

The epiphyseal plate makes up the humerus’ anatomical neck. An intertubercular groove visible proximally separates the two tubercles vertically.

The surgical neck of the humerus, which is frequently prone to fractures, comes after the tubercles.

The cylindrical shaft of the humerus extends distally, ending in a deltoid tubercle on the lateral aspect and a radial groove, also called the spiral groove, on the posterior aspect.

At the distal end of the humerus, the bone that comprises the medial and lateral epicondyles expands. The condyle, where the distal end of the humerus ends, is made up of the trochlea, capitulum, olecranon, coronoid, and radial fossae.

On the anterior lateral surface of the condyle is the lateral capitulum, which articulates with the radius bone head, and on the anterior medial surface of the condyle is the trochlea, which articulates with the trochlear notch of the ulna bone.

The radial fossa, which houses the coronoid process of the ulna and receives the head of the radius during elbow flexion, is located on the anterior aspect of the condyle, above the capitulum.

This is the coronoid fossa, and it is located above the trochlea. When the elbow joint flexes, the olecranon of the ulnar bone articulates with the olecranon fossa, which is situated on the posterior surface of the condyle.

Where is the humerus located?

Between the elbow and shoulder joints in the upper arm is where you’ll find the humerus bone. The glenohumeral joint, which is another name for the shoulder joint, is a ball and socket joint. The glenoid fossa of the scapula serves as the socket, and the ball is the humeral head.

The four rotator cuff muscles and their tendons—the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis—encircle the joint and are supported by ligaments. These muscles attach to the humeral head after originating on the scapula.

The area of the humerus most vulnerable to fracture is the proximal humerus. The anatomical neck of the humerus is located below the head, and the greater and lesser tubercles—projections in the bone—come next.

The operative neck is located beneath the tubercles. Most proximal humerus fractures happen in the surgical neck, particularly in older people who have osteoporosis.

The distal humerus and the proximal humerus are joined by the bone shaft. The two arm bones that make up the forearm, the radius and ulna, articulate with the distal humerus at the elbow joint.

Anatomy of the Humerus

The humerus is composed of three parts: a long shaft in the middle, a rounded end where it meets your shoulder, and a flatter end that creates your elbow joint. The top portion is shaped like a ball and slides into your shoulder socket.

Your humerus is a single long bone, but it is actually composed of multiple parts.

Among them are:

The upper part of the bone

The large, rounded head of the humerus is connected to the body by a narrow section known as the neck, and it has two eminences, the greater and lesser tubercles, which make up its upper or proximal extremities.

Head

The head, or caput humeri, has a shape that is almost hemispherical. The glenohumeral joint, or shoulder joint, is formed when it articulates with the glenoid cavity of the scapula. It is directed upward, medially, and slightly backward.

Its articular surface has a slightly constricted circumference known as the anatomical neck. This is not to be confused with the surgical neck, which is a constriction below the tubercles and often the site of fractures.

Anatomical neck fractures are uncommon. Men typically have a larger humeral head diameter than women do.

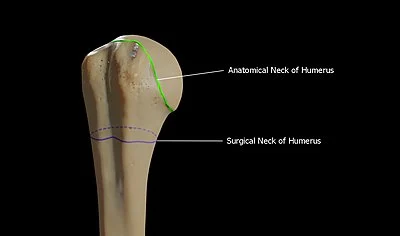

Anatomical neck

The anatomical neck forms an obtuse angle with the body due to its oblique orientation. It is most prominent in the lower half of its circumference; in the upper half, a thin groove that divides the head from the tubercles serves as a representation of it.

The term “anatomical neck” refers to the boundary that divides the head from the remainder of the upper body. It is perforated by multiple vascular foramina and provides attachment to the shoulder joint’s articular capsule. Anatomical neck fractures are uncommon.

The articular capsule attaches to an indentation on the anatomical neck of the humerus, which is located distal to the humeral head.

Surgical neck

The surgical neck is a small, distal region near the tubercles that frequently experiences fractures. It comes into contact with the posterior humeral circumflex artery and the axillary nerve.

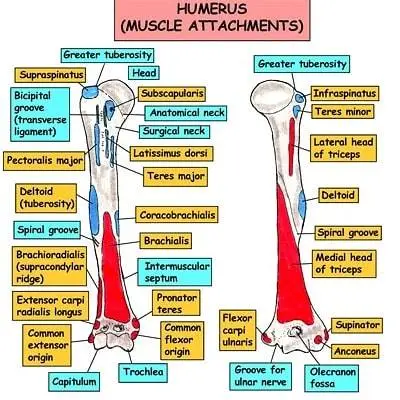

Greater tubercle

The larger tubercle is a large laterally oriented posterior projection. The supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor muscles are attached to the greater tubercle.

The pectoralis major inserts into the crest of the greater tubercle, which also forms the lateral lip of the bicipital groove.

The anatomical neck is directly lateral to the larger tubercle. Its upper surface is rounded and has three flat impressions on it: the insertion of the supraspinatus muscle is located at the highest point, the infraspinatus muscle is located in the middle, and the teres minor muscle is located at the lowest point, along with the body of the bone for approximately 2.5 cm below it.

The body’s lateral surface and the greater tubercle’s lateral surface are continuous, rough, and convex.

Lesser tubercle

Located anterolaterally to the head of the humerus, the lesser tubercle, also known as the tuberculum minus or lesser tuberosity, is smaller. The subscapularis muscle receives its insertion from the lesser tubercle. These two tubercles are located in the shaft’s proximal region.

The smaller tuberosity is located in front and faces both forward and medially, making it more noticeable than the larger tuberosity. It displays an impression of the subscapularis muscle’s tendon insertion above and below.

Bicipital groove

The bicipital groove, a deep groove that houses the long tendon of the biceps brachii muscle and carries a branch of the anterior humeral circumflex artery to the shoulder joint, divides the tubercles from one another.

It ends close to the point where the upper and middle thirds of the bone converge, running obliquely downward.

When it is still fresh, the latissimus dorsi muscle tendon inserts into its lower portion, while its upper part is lined by a thin layer of cartilage that is a prolongation of the shoulder joint’s synovial membrane.

As it descends, it becomes shallower and slightly wider after becoming deep and narrow above. Its lips form the upper portions of the anterior and medial borders of the bone’s body. They have named the crests of the greater and lesser tubercles, or bicipital ridges, respectively.

Shaft

Body of long bone Humerus

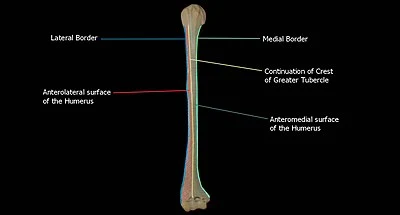

The region between the lateral border of the humerus and the line drawn as the greater tubercle’s crest continues is known as the anterolateral surface. The anterolateral surface faces two directions: forward and lateralward below, where it is slightly concave from above downward and gives origin to part of the Brachialis; and lateralward above, where the deltoid muscle covers it and it is smooth and rounded.

The deltoid tuberosity, where the deltoid muscle inserts, is a rough, rectangular elevation located roughly in the center of this surface. The radial sulcus, which transmits the profunda artery and radial nerve, is located below this. It is oriented obliquely forward, downward, and behind.

Surface

The humerus’s body, or shaft, is compressed anteroposteriorly and has a cut section that ranges from triangle to cylindrical.

There are three surfaces to it:

- Anterolateral surface

The region between the lateral border of the humerus and the line drawn as the larger tubercle’s crest continues is known as the anterolateral surface.

The anterolateral surface faces two directions: forward and lateralward below, where it is somewhat concave from above downward and gives origin to a portion of the Brachialis; and lateralward above, where It is covered by the deltoid muscle and is spherical and smooth.

The radial sulcus, which transmits the profunda artery and radial nerve, is located below the rough, rectangular elevation known as the deltoid tuberosity, which is about in the center of this surface.

This elevation is where the deltoid muscle insertion is located.

- Anteromedial surface

The region between the humerus’ medial border and the line that continues the larger tubercle’s crest is known as the anteromedial surface.

Less expansive than the anterolateral surface, the anteromedial surface is directed medially above, forward, and medially below.

Its upper portion is narrow, forming the floor of the intertubercular groove where the latissimus dorsi muscle tendon insertion is found; its middle portion is slightly rough, serving as a point of attachment for some of the fibers of the coracobrachialis muscle tendon insertion; and its lower portion is smooth, concave from above downward and originating the brachialis muscle.

- Posterior surface

The space between the medial and lateral boundaries is known as the posterior surface.

The posterior surface exhibits a little twist, with the upper portion pointing slightly medial and the lower portion pointing backward and somewhat lateralward.

The lateral and medial heads of the Triceps brachii, which arise above and below the radial sulcus, encompass almost the whole area.

Borders

Its three boundaries are as follows:

- Anterior border

The anterior border divides the anteromedial from the anterolateral surface, extending from the front of the larger tubercle above to the coronoid fossa below.

The pectoralis major muscle-tendon attachment point is located on its upper portion, which is a conspicuous ridge known as the crest of the larger tubercle.

Its center serves as the anterior deltoid tuberosity boundary, to which the deltoid muscle is attached; below, it is rounded and smooth, providing a surface for the brachialis muscle to attach.

- Lateral border

This line that divides the anterolateral from the posterior surface extends from the rear of the larger tubercle to the lateral epicondyle.

Its rounded, poorly defined upper half is where the lateral head of the triceps brachii muscle originates, and it serves as the attachment point for the lower portion of the teres minor muscle’s insertion.

A broad, shallow oblique depression runs through the middle of it, called the spiral groove (musculospiral groove).

The spiral groove is where the radial nerve runs. Its lower portion creates a noticeable, rough edge that is slightly bent forward and forward to form the lateral supracondylar ridge.

This ridge has an anterior lip that represents the origin of the brachioradialis muscle above, a posterior lip that represents the triceps brachii muscle, and an intermediate ridge that serves as the lateral intermuscular septum’s attachment.

- Medial border

The lesser tubercle and the medial epicondyle are separated by the medial boundary. The crest of the lesser tubercle, a noticeable ridge in its upper third, is where the tendon of the teres major muscle inserts.

A small indentation for the coracobrachialis muscle insertion is located in its center, and directly under it is the nutrient canal’s entrance, which faces downward.

Occasionally, a second nutritional canal is located at the beginning of the radial sulcus.

It presents an anterior lip for the origins of the brachialis and pronator teres muscles, a posterior lip for the medial head of the triceps brachii muscle, and an intermediate ridge for the attachment point of the medial intermuscular septum.

The inferior third of this border develops into a slight ridge, the medial supracondylar ridge, which became very prominent below.

Deltoid tuberosity

The deltoideus muscle inserts into the Deltoid tuberosity, a roughened area on the lateral aspect of the Humerus shaft.

There is a crest on the posterosuperior portion of the shaft, which starts just below the humeral surgical neck and extends to the superior point of the deltoid tuberosity.

The lateral head of the triceps brachii attaches to this point.

The radial sulcus

The radial nerve and deep vessels flow via the radial sulcus, also called the spiral groove, which is a shallow, oblique groove on the posterior surface of the shaft.

Posteroinferior to the deltoid tuberosity is where this is situated. The lateral border of the shaft and the inferior boundary of the spiral groove are continuous distally.

The nutrient foramen

Situated on the anteromedial surface of the humerus is the nutritional foramen. This foramen allows the nutritional arteries to enter the humerus.

The distal part of the humerus

The humerus’ distal extremity is flattened from the front to the back and curved slightly forward.

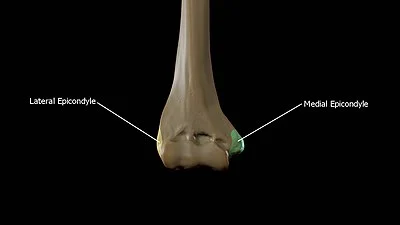

It finishes below with a large articular surface that is split into two sections by a little ridge. The lateral and medial epicondyles protrude laterally on both sides.

Articular surface

The medial extremity of the articular surface is lower than the lateral, and it is somewhat bent forward, extending slightly below the epicondyles.

This surface’s lateral section is made up of a smooth, rounded protrusion that is only present on the front and lower portions of the bone and is called the capitulum of the humerus.

It connects with the cup-shaped depression at the head of the radius.

Fossa

When the forearm is flexed, the coronoid process of the ulna is received by the coronoid fossa, a little depression located above the front portion of the trochlea.

- Olecranon fossa

The olecranon fossa, a deep triangular dip over the back of the trochlea, is where the forearm extends to accept the olecranon’s summit.

- Coronoid fossa

The medial hollow portion on the anterior aspect of the distal humerus is known as the coronoid fossa. When the elbow reaches its greatest flexion, the coronoid process of the ulna is received by the coronoid fossa, which is smaller than the olecranon fossa.

- Radial Fossa

When the forearm is flexed, the anterior edge of the radius head is received by the radial fossa, a small depression located above the front portion of the capitulum.

The synovial membrane of the elbow joint lines these fossa in their fresh state, and their margins allow attachment to the anterior and posterior ligaments of this articulation. These fossa are separated from one another by a thin, transparent lamina of bone, which is occasionally perforated by a supratrochlear foramen.

Capitulum

The lateral portion of the distal humerus is formed by the rounded eminence known as the capitulum. The capitulum and the head of the radius articulate.

The trochlea

The ulna articulates with the trochlea, the medial part of the distal humerus fashioned like a spool.

The ulna articulates with the trochlea, the medial part of the distal humerus fashioned like a spool.

Epicondyles

The supracondylar ridges and the epicondyles are continuous above.

- The lateral epicondyle

The lateral epicondyle is a tiny, tuberculated protrusion that is slightly bent forward. It attaches to the elbow joint’s radial collateral ligament as well as a tendon that is shared by the origins of the extensor and supinator muscles.

- The medial epicondyle

The ulnar nerve runs in a groove on the back of the medial epicondyle, which is larger and more prominent than the lateral.

It is directed slightly backward and provides attachment to the Pronator teres, the ulnar collateral ligament of the elbow joint, and a common tendon of origin of some of the forearm flexor muscles.

- The medial supracondylar crest

The distal humerus’s strong medial edge is formed by the medial supracondylar crest, which extends superiorly from the medial epicondyle.

- The Lateral Supracondylar crest

The distal humerus’s strong lateral edge is formed by the Lateral Supracondylar crest, which extends superiorly from the Lateral Epicondyle.

Articulation

The glenoid fossa of the scapula and the head of the humerus articulate at the shoulder.

The trochlea of the humerus articulates with the trochlear notch of the ulna, while the capitulum of the humerus articulates with the head of the radius at the elbow, further distally.

Nerves

At the proximal end, up against the shoulder girdle, is where you’ll find the axillary nerve. The axillary nerve or artery may be injured by dislocation of the glenohumeral joint in the humerus.

A palpable dip beneath the acromion and a loss of the typical shoulder shape are indications of this dislocation.

The radial nerve roughly tracks the humerus. The radial nerve passes through the spiral groove at the midshaft of the humerus, moving from the posterior to the anterior portion of the bone.

Radial nerve damage can arise from a humeral fracture in this area.

The bone is sometimes called “the funny bone” by the general public, presumably as a result of both this feeling and the name of the bone being a homophone for “humorous.”

It is prone to damage from elbow injuries and is located posterior to the medial epicondyle.

What is the function of the humerus?

In addition to offering structural support, the humerus is where numerous significant muscle insertion points are located. The latissimus dorsi (also known as “lats”) and pectoralis major (also known as “pecs”) muscles join to the intertubular sulcus, or groove, in the humerus head and aid in humeral rotation.

The humerus is the attachment point for a number of other muscles that enable movement in the arm and upper body, such as the deltoids, brachioradialis, coracobrachialis, pronator teres, teres major, brachialis, common flexor, and extensor tendons.

Numerous veins and arteries run the length of the humerus bone. The majority of the humerus bone is made up of the brachial artery, the main blood vessel in the upper arm.

It splits into the radial and ulnar arteries at the elbow joint, supplying blood to the forearm. Additionally, the basilic vein passes near the humerus and aids in the drainage of the hand and forearm.

Additionally, the humerus is the path used by brachial plexus nerves. Similar to this, the radial nerve rotates along the bone halfway down the humeral shaft. Damage to the radial nerve can result from fractures in this area.

Your humerus serves two vital purposes. They are assistance and mobility. Let’s investigate them a little more thoroughly.

Your humerus connects to your elbow and shoulder to enable a multitude of arm movements, including:

- Rotation at the shoulder joint

- Extending the arms (abduction) away from your body

- Adduction: bringing your arms back down to your body

- Extending your arm to the back of your body

- Flexion: the act of moving your arm in front of your body

- Extending your elbow to its full length

- Flexion, or elbow bending

Your humerus is necessary for support as well as for a variety of arm movements. For instance, the muscles in your arm and shoulder are connected via certain areas of the humerus.

Muscles attachment

Numerous muscles of the upper limb, which are classified as scapulohumeral, anterior compartment, and posterior compartment muscles, originate from their insertion point on the humerus.

Scapulohumeral muscles

The acromion of the scapula, the scapula’s spine, and the clavicle are the three points of origin of the deltoid muscle, which forms the upper limb’s shoulder contour.

The deltoid muscle permits humeral abduction and adduction as well as internal and exterior rotation.

The pectoralis major

The clavicle, manubrium, sternum body, and true ribs are the points of origin of the pectoralis major muscle, which inserts into the humerus’s intertubercular sulcus.

It permits the humerus to adduction, flexion, extension, and medial rotation.

The rotator cuff

The muscles of the teres minor, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and subscapularis comprise the rotator cuff.

The subscapularis muscle

The subscapularis muscle emerges from the subscapular fossa of the scapula and attaches itself to the lesser tubercle of the humerus to facilitate internal rotation of the humerus.

The supraspinatus muscle

The supraspinatus muscle helps with humerus abduction by inserting into the larger tubercle of the humerus from its origin in the supraspinous fossa of the scapula.

The infraspinatus muscle

The larger tubercle of the humerus receives an insert from the infraspinous fossa and scapula spine, the infraspinatus muscle, which permits external rotation of the humerus.

The teres major

Allowing for internal rotation and adduction, the teres major originates at the inferior angle of the scapula and inserts into the lesser tuberosity of the humerus.

The teres minor

Originating on the lateral border of the scapula, the teres minor inserts into the larger tubercle to facilitate external rotation.

Muscles of the anterior compartment

The biceps brachii muscle

The biceps brachii muscle lacks a real origin or insertion point on the humerus, however it does have a long and short head.

But the tendon of the biceps brachii long head passes through the transverse humeral ligament, which extends from the lesser tubercle to the greater tubercle of the humerus and changes the humeral intertubercular groove into a canal.

This tendon begins at the scapula’s supraglenoid tubercle and finishes at the radius.

The coracobrachialis

The scapula’s coracoid process is the starting point of the coracobrachialis, which inserts onto the humerus’ medial surface to provide flexion and internal rotation.

Muscles of the posterior compartment

The triceps brachii

Three heads make up the triceps brachii muscle: the lateral head originates on the posterior surface of the humerus, inferior to the spiral groove, and the medial head originates on the posterior aspect of the humerus.

Forearm extension at the elbow joint is made possible by both heads inserting into the olecranon process of the ulna.

Notably, the posterior circumflex artery, vein, and radian nerve pass via a quadrangular gap formed by the humerus, the long head of the triceps, and the teres major and teres minor.

Lymphatic System and Blood Supply.

The proximal humerus receives its primary blood supply from the anterior and posterior circumflex humeral arteries anastomose.

These branches originate from the axillary artery’s distal portion. Recent studies suggest that the humeral head’s primary blood supply may come from the posterior humeral circumflex artery.

The arcuate artery, which supplies most of the larger tuberosity, is the final division of the anterior humeral circumflex artery.

The axillary artery proceeds to develop into the brachial artery, which will deliver blood to the rest of the humerus and the muscles linked to it, along with the profunda brachii artery, one of its branches.

Nutrient arteries, which likewise split off from the brachial artery near the humerus’s midpoint, supply blood to the inner parts of the bone.

Nerves

The axillary nerve, derived from the posterior chord of the brachial plexus, encircles the humeral surgical neck and supplies innervation to the rotator cuff and deltoid muscles, with particular emphasis on the teres minor.

The musculocutaneous nerve, which arises as a division of the brachial plexus’s lateral cord, innervates the anterior part of the brachium.

After going through the coracobrachialis muscle and between the biceps brachii and coracobrachialis, the nerve stops at the lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm.

It innervates the posterior arm muscles, surrounding skin, and forearm. The radial nerve also innervates the lateral and medial epicondyles of the humerus.

Notably, the ulnar and median nerves do not innervate this region even though they also come from the brachial plexus and descend the brachium.

The radial nerve crosses the posterior chord of the brachial plexus, the spiral groove of the humerus, the long head of the triceps, and the brachial artery.

- The axillary nerve

At the proximal end, up against the shoulder girdle, is where you’ll find the axillary nerve. The axillary nerve or artery may be injured by dislocation of the glenohumeral joint in the humerus. A palpable dip beneath the acromion and a loss of the typical shoulder shape are indications of this dislocation.

- The radial nerve

The radial nerve roughly tracks the humerus. The radial nerve passes through the spiral groove at the midshaft of the humerus, moving from the posterior to the anterior portion of the bone. Radial nerve damage can arise from a humeral fracture in this area.

- The ulnar nerve

The ulnar nerve is located close to the elbow at the distal end of the humerus. It can provide a noticeable tingling feeling when struck, as well as occasionally severe pain.

Because of this “funny” feeling and the fact that the name of the bone is a homophone for “humorous,” it is sometimes referred to as “the funny bone” in popular culture. It is prone to damage from elbow injuries and is located posterior to the medial epicondyle.

The study of embryology

The humerus is a long bone that grows through endochondral ossification, one of the several long bones in the appendicular skeleton.

This process is characterized by the replacement of a cartilage template with bone. A relatively small model of cartilage is first laid down by mesenchymal cells that give rise to chondrocytes that secrete cartilage.

Second, chondrocyte hypertrophy and the production of substances like alkaline phosphatase that encourage calcification of that cartilage are present in the ossification center, the core of the cartilage template. This results in a nutritional blockage and chondrocyte death.

But these cells also release vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) to promote angiogenesis within the calcifying cartilage prior to death.

In the meantime, cells outside the perichondrium convert into osteoblasts under the influence of the Indian hedgehog homolog (IHH) protein, forming a layer of bone known as the bony collar that surrounds the cartilage center.

Over time, a core area of dead chondrocytes develops, encircled by a circulatory supply, a shell of bone, and tiny pieces of calcified cartilage.

The internal mesenchymal cells that transform into additional osteoblasts and monocytes that produce osteoclasts are brought in by the circulatory supply.

Bone is resorbed on the inside and deposited on the outside in the center of the original cartilage template, causing the hollow entity (forming a marrow) to widen.

Concurrently, as secondary ossification centers, chondrocytes continue to proliferate at the proximal and distal ends of the cartilage template.

This process enables the formation of cartilage at the end of the bones, enabling vertical expansion. Ultimately, the intersection of bone and cartilage forms the linear zone of cartilage known as the epiphyseal plate. Here, cartilage replaces bone continually until bone growth fully fuses and ceases at puberty.

There are eight distinct ossification foci in the humerus: the humeral shaft, the medial and lateral epicondyles, the olecranon, the larger and lesser tubercles, and the head of the humerus.

Clinical anatomy

Damage to the Radial Nerve

After a humeral fracture, one of the most frequent peripheral nerve injuries is radial nerve palsy.

Unless nerve healing (as shown by EMG/NCS testing) does not occur within 3 to 6 months, treatment usually consists of observation.

Proponents of early radial nerve exploration point to substantial internal patient function loss and delayed healing as reasons against the delayed investigation. Trauma or fracture at the mid-shaft or radial groove can cause injury to the radial nerve.

Condition of the Shoulder

Adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder (also known as frozen shoulder syndrome) and calcific tendinitis of the rotator cuff are two rather frequent disorders with debatable and/or complex etiologies.

Surgery is rarely required; the mainstays of treatment are rest and exercise. On the other hand, infiltration basement under general anesthesia can be used for surgical care of frozen shoulder syndrome.

Metastatic Illness

Destructive bone lesions and severe localized pain are symptoms of metastatic bone disease, which typically affects the humerus. The chance of a humeral fracture might be raised by lesions.

External beam irradiation is used as a form of treatment for patients whose lesions do not cover 50% of the cortex. However, intramedullary nailing combined with postoperative external beam radiation is the therapy of choice for devastating lesions covering more than half of the cortex. If the illness worsens, bone excision or reconstruction may be necessary.

Supracondylar Fractures of the Distal Humerus

In children, this is the most frequent type of elbow fracture. The epicondyles, medial and lateral condyles, and fracture location are all superior.

Depending on how much the fracture is displaced, supracondylar fractures of the distal humerus near the elbow joint might impair nerve and vascular.

The brachial artery and median nerve are at risk from anterior displacement. A posterior displacement can be dangerous to the radial artery. As part of the first workup to check for intact blood supply, distal pulse palpation, and capillary refill should be performed.

Radiographs taken from the front, back, and side are required for precise diagnosis and care. Initial treatment for nondisplaced fractures involves a posterior splint, followed by casting.

Fractures that have displaced are reduced and percutaneously pinned. Morbidities associated with this fracture include neurovascular problems, compartment syndrome, and malunion.

Fractures in the humerus

A bone fracture is the term used by doctors to describe breaking a bone. Traumatic incidents, such as falls or auto accidents, can result in humerus fractures. Additionally, some persons who play sports sustain humerus fractures.

Among the signs of a fracture are:

- Pain

- Swelling

- Tenderness

- unable to move your arm as freely as you normally can.

- Any discoloration or bruises.

- A lump or abnormality that doesn’t belong on your body.

If you believe you may have a fracture or have received trauma, get to the emergency department as soon as possible.

The osteoporosis

Because osteoporosis weakens bones, fractures that occur suddenly and unexpectedly are more likely to occur.

Many people have osteoporosis without realizing it until one of their bones fractures. Usually, there aren’t any overt signs.

Osteoporosis is more common in women or those classified as female at birth (AFAB) and in those over 50. To prevent fractures and detect osteoporosis early, ask your doctor about a bone density test.

Summary

Between the elbow and shoulder joints in the upper arm is the humerus, a long bone. The glenoid fossa of the scapula is where the proximal humerus joins the shoulder to form the glenohumeral joint. In the forearm, the distal humerus articulates at the elbow to the ulna and radius.

In addition to providing structural support for the arm, the humerus is where a number of significant upper body muscles, including the rotator cuff muscles, pectoralis major, and latissimus dorsi, insert.

The basilic vein runs nearby and aids in the drainage of some areas of the hand and forearm, while the brachial artery likewise follows the humerus, delivering oxygen and other nutrients to the arm through the blood. Moreover, the ulnar and radial nerves run.

FAQ

Where is the humerus bone located?

Between the elbow and shoulder joints in the upper arm is where you’ll find the humerus bone. The glenohumeral joint, which is another name for the shoulder joint, is a ball and socket joint. The glenoid fossa of the scapula serves as the socket, and the ball is the humeral head.

What is the humerus and its function?

The bone in your upper arm that is between your elbow and shoulder is called the humerus. Its primary purpose is to support your shoulder and allow your arm to move in a multitude of ways.

Why is it called a surgical neck?

The area directly below the head is known as the anatomical neck. The neck continues down the humerus body and is referred to as the surgical neck (so named because many fractures that need surgery occur here).

What is the humerus bone in vertebrates?

The humerus is the long bone of the upper limb or forelimb of terrestrial vertebrates. It forms the elbow joint below, where it articulates with projections of the ulna and radius, and the shoulder joint above, where it articulates with a lateral depression of the shoulder blade (glenoid cavity of the scapula).

What is a humerus fracture?

The medical term for fracturing the bone in your upper arm (your humerus) is a humerus fracture. Traumas like falls or auto accidents are typically the cause of humerus fractures. In order to fix your broken humerus, surgery may be necessary.

What is the head of the humerus?

The upper extremity’s proximal articular surface, an uneven hemisphere, is known as the head of the humerus. It articulates with the scapula’s glenoid fossa. The region between the shaft and the tuberosities is known as the surgical neck.

Reference

- Humerus. (n.d.). Physiopedia. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Humerus

- https://www.osmosis.org/answers/humerus

- Mostafa, E. (2023, August 7). Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Humerus. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534821/

- Seladi-Schulman, J. (2022, February 28). The Humerus Bone: Anatomy, Breaks, and Function. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/humerus-bone#humerus-fractures

- Humerus. (n.d.). Physiopedia. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Humerus

- Professional, C. C. M. (n.d.). Humerus. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/24612-humerus

2 Comments