Plantar Fibroma

What is Plantar Fibroma?

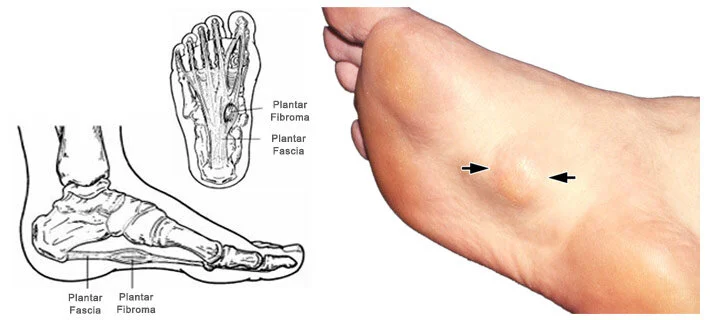

A plantar fibroma refers to a fibrous nodule within the arch of the foot, nestled within the plantar fascia, a tissue band stretching from the heel to the toes on the underside of the foot.

This benign (nonmalignant) condition can manifest in either one or both feet and typically persists or enlarges without intervention. While definitive causes remain elusive, various treatment options exist to address plantar fibromas.

Introduction

A plantar fibroma manifests as a connective tissue knot, a benign nodule that can emerge anywhere in the body. In the case of the foot, this fibrous lump settles in the arch, presenting a persistent issue that requires attention. Unlike malignant growths, plantar fibromas don’t spread but linger, necessitating treatment for resolution.

This foot-afflicting fibroma contributes to discomfort by forming a noticeable lump on the foot’s arch, triggering pain exacerbated with each step or pressure application. Footwear choices can further intensify this discomfort, leading to daily unease that may evolve into an intolerable state.

The precise origin of these foot nodules remains uncertain, although some experts speculate that they originate from minor tears in the plantar fascia due to trauma. The subsequent nodules arise as a consequence of the scar tissue formed during the healing process.

While plantar fibroma isn’t exclusive to a particular age group, it predominantly affects those in middle age and beyond. Intriguingly, men encounter these nodules twice as frequently as women, yet the underlying cause of this gender disparity remains elusive.

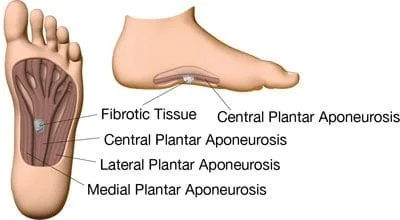

Anatomy and biomechanics of the plantar fascia

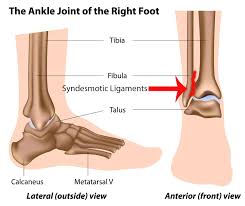

The plantar fascia is a large fibrous aponeurosis that begins at the base of the proximal phalanges, inserts distally into the periosteum at the metatarsophalangeal joints, and separates into five digital slips at the medial and anterior portions of the calcaneus. The central, medial, and lateral bands of thick connective tissue make up its composition. PF is more frequently seen in the central and medial bands.

Maintaining the longitudinal plantar arch is the principal job of the plantar fascia. The plantar fascia’s high tensile strength—especially while bearing weight—helps to achieve this in part. The plantar fascia tightens, the gap between the calcaneus and metatarsals is shortened, and the medial longitudinal arch is raised when a person dorsiflexes their toes. The windlass mechanism is the name given to this dynamic mechanism because it functions similarly to how an efficient and reliable cable-tightening process works. This sequence of actions is essential for maintaining the gait cycle, as even a little arch collapse can result in significant walking inefficiency.

Epidemiology of Plantar Fibroma

The prevalence and etiology of plantar fibroma (PF) are not currently fully understood. Although the exact number of affected individuals hasn’t been precisely assessed, the disease remains listed as a rare condition by the National Institute of Health, impacting fewer than 200,000 people. Multiple studies indicate that those affected by plantar fibroma often experience a significant reduction in their quality of life and substantial functional disability.

Plantar fibroma primarily affects individuals in their middle years, with some cases reported in children under 16 years and even as young as 9 months. Men are more frequently affected than women and bilateral disease occurs approximately 25% of the time. It often coexists with hyperproliferative fibromatosis in other appendages, such as Dupuytren’s disease in the hands, Peyronie’s disease in the penis, or more generalized keloid formation.

Associated conditions include frozen shoulders, alcohol addiction, diabetes, epilepsy, smoking, repeated trauma, and prolonged phenobarbital use. A recent genome-wide association study has suggested a potential genetic predisposition to plantar fascial disorders, including plantar fascia.

Causes of Plantar Fibroma

The precise cause of plantar fibroma remains elusive, presenting as a condition with a multifactorial origin. Factors contributing to its development include congenital and traumatic influences, along with instances of prolonged immobilization followed by trauma.

Individuals with Dupuytren’s contractures, diabetes mellitus, epilepsy, alcohol-related liver disease, engaging in stressful work, and a predisposition to keloids face an elevated risk of developing Ledderhose disease and/or Peyronie’s disease.

Symptos of Plantar Fibroma

The distinctive nodule in Plantar Fibroma (PF) typically ranges from 0.5 to 3.0 cm in diameter, exhibiting slow growth and positioning within the medial or central plantar aponeurosis. Unlike Dupuytren’s disease, these nodules generally spare smooth muscle tissue and skin, minimizing the likelihood of contractions. However, severe proliferation and infiltration of the nodule can lead to toe contractures, including the great toe. Symptoms vary, ranging from localized pressure and distension to painless nodules and tender, erythematous lesions impacting weight-bearing ability.

Most commonly, patients report a gradual lump formation along the medial longitudinal arch, initially painless but becoming increasingly uncomfortable with enlargement. Discomfort intensifies with restrictive shoes, direct pressure, barefoot walking, and prolonged standing. Over time, multiple fibromas may develop, contributing to worsening symptoms.

An accurate diagnosis relies on a thorough physical examination. Visual assessment identifies potential swelling, skin breakdown, bruising, or deformity, while palpation of bony prominences and tendinous insertions is crucial. A note of Achilles tendon or gastrocnemius contracture is important, along with assessing ankle and hindfoot motion and observing the patient’s gait. Differential diagnosis considerations encompass calcaneal stress fractures, tarsal tunnel syndrome, and plantar fasciitis.

While a well-defined nodule along the plantar fascia is indicative of fibromatosis, additional pathologies may coexist. The squeeze test aids in identifying calcaneal stress fractures, and tarsal tunnel syndrome is recognized by pain and numbness radiating to the plantar heel upon tibial nerve percussion. Tenderness over the medial aspect of the calcaneal tuberosity is the initial sign of plantar fasciitis.

The natural history of plantar fibroma unfolds in three phases: a proliferative phase marked by increased fibroblastic activity, an active phase featuring nodule formation, and a residual phase characterized by collagen maturation, scar formation, and tissue contracture.

While diagnosis primarily relies on history and physical examination, imaging serves as a confirmatory tool, and in specific cases, a biopsy may be warranted to rule out malignancies.

Differential Diagnosis

Plantar fibroma is occasionally linked with concomitant conditions like:

- Dupuytren’s disease

- Peyronie’s disease

- Knuckle pads

Other primary differential diagnoses encompass:

- Epilepsy

- Diabetes

- Alcohol addiction

- Plantar fasciitis

- Chronic rupture of the plantar fascia

Diagnostic Procedures for Plantar Fibroma

Identification of lesions, extensions, characteristics, and structures involved in plantar fibroma, as well as assessing local recurrence, can be accomplished through various imaging modalities:

- Ultrasound: Offers visualization of well-defined nodules, enabling identification of the characteristics and structures involved. The sharp juxtaposition between the fibroma and the brighter plantar fascia is distinct. Doppler ultrasound is seldom indicative of vascular flow within the lesion.

- MRI: Provides a detailed view of plantar fascia, depicting a well-defined nodule continuous with the plantar fascia. Notably, it exhibits low signal intensity on T1-weighted sequences and low to intermediate signal intensity on T2-weighted sequences. Larger, lobulated lesions that are continuous with the plantar fascia are also recognized. Gadolinium administration may reveal variable enhancement.

- CT Scan: utilized for tissue comparison, particularly to identify tissue masses in characteristic areas. It identifies non-specific tissue masses with attenuation equal to or higher than skeletal muscles.

Imaging:

Distinguishing plantar fascia lesions from other plantar fascia lesions is facilitated by ultrasound and MRI. MRI reveals focal, oval-shaped areas of disorganization within the plantar fascia, with larger lobulated lesions also observed. These lesions typically exhibit low signal intensity due to their fibrous nature, although some may appear signal-isointense with the muscle. Variable enhancement is noted with gadolinium administration.

Ultrasound showcases characteristic PF presentation, featuring multiple lesions embedded on the plantar fascia, with a distinct contrast between the reflective fibroma and the brighter plantar fascia. The “Comb Sign,” a novel morphologic appearance described by Cohen et al., is visible in a significant percentage of cases, demonstrating alternating linear bands of hypoechogenicity and isoechogenicity akin to teeth on a comb.

This sign enhances the characterization of fibromas, showcasing hyperechoic, fibrous regions against a hypoechogenic cellular matrix. Advances in musculoskeletal ultrasound resolution contribute to this enhanced characterization. Notably, the “comb sign” is present in approximately 51% of cases studied, offering a valuable diagnostic feature.

Non-Operative Management for Plantar Fibroma

Various non-surgical approaches are available for the symptomatic management of plantar fibroma, each backed by varying degrees of scientific evidence. Considering their generally low morbidity, employing conservative measures before resorting to surgery is a prudent approach.

- Steroid Injections:

Steroid injections, a common initial strategy for managing plantar fasciitis, aim to shrink nodules, alleviating associated pain during ambulation. These injections modulate the expression of VCAM1 and alter the production of the pro-inflammatory cytokines TGF-β and bFGF. While providing temporary relief, recurrence to the original nodule size within three years post-treatment is noted. Multiple injections, typically 3–5 administered every 4–6 weeks, are common, although the optimal dosage remains undetermined. Caution is advised due to the increased risk of fascial or tendon rupture with multiple injections. - Verapamil:

Verapamil, a calcium channel blocker used primarily for blood pressure management, influences the extracellular matrix’s metabolism. It inhibits collagen production and enhances collagenase activity, reducing fibroblast and myofibroblast contractile function. Anecdotal evidence supports its use in conservative plantar fibroma management, although limited published data assess its efficacy. Transdermal verapamil cream and intralesional verapamil have demonstrated efficacy in related conditions like Peyronie’s, suggesting potential applicability in plantar fibroma. - Radiation Therapy:

Utilized in the early stages, radiation therapy reduces fibroblast proliferative activity by disrupting TGF-β production. Effective treatment involves weekly doses of 3.0 Gy for 5 weeks, with an additional session after 6 weeks, totaling 30.0 Gy. Adverse effects include skin changes, lethargy, local oedema, and pain. Studies indicate complete or partial remission in a significant portion of patients, making radiation therapy a viable option for reducing nodule size and alleviating symptoms. - Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy (ESWT):

A newer treatment option, ESWT, induces a biochemical response in tendon fibroblasts, impacting tendon metabolism. While not altering nodule size, ESWT effectively reduces pain and softens the fascia and nodules. Its success in related conditions, such as Peyronie’s and Dupuytren’s, suggests its potential as a therapeutic option for pain relief and improved functionality. - Tamoxifen:

Exploring the role of estrogen in fibroblast contractile properties, antiestrogen therapy, specifically tamoxifen, shows promise in inhibiting contracture rates and TGF-β release. Though lacking in vivo studies, in vitro studies indicate tamoxifen’s potential to prevent disease progression by reducing contractures and fibroblast proliferation. - Collagenase:

Collagenase Clostridium histolyticum (CCH), effective in related conditions like Peyronie’s and Dupuytren’s, is being studied for plantar fibroma. Initial findings with monthly injections for three months did not show improvement in nodule size or pain. The anatomical differences between PF and other conditions may contribute to CCH’s limited effectiveness for PF, emphasizing the need for further studies. Adverse effects are minimal, including erythema, ecchymosis, and pain at the injection site.

These non-operative modalities offer diverse options for managing plantar fibroma symptoms, providing patients with choices tailored to their preferences and the nature of the condition.

Operative Management for Plantar Fibroma

Considering the typically benign nature of plantar fibroma, surgical intervention is generally reserved for cases where pain relief is essential. Current surgical indications encompass pain that is unresponsive to conservative treatments and instances where the lesion exhibits local aggressiveness. Concerns about recurrence with partial excision have led to historical preferences for a complete plantar fasciectomy.

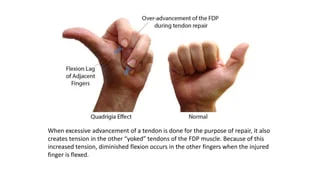

Recent advances introduce three main surgical techniques for managing plantar nodules: local excision, wide excision, and complete fasciectomy. Studies indicate that local excision has the highest recurrence rates, ranging from 57% to 100%. Wide excision involves removing a 2–3 cm margin of surrounding tissue along with the nodule, showing a slightly lower recurrence rate of approximately 8%–80%.

A complete fasciectomy, removing the entire plantar fascia, boasts the lowest recurrence rates at approximately 0%–50%. Some surgeons advocate for partial fasciectomy, emphasizing its ability to remove diseased tissue with less presumed morbidity than total fasciectomy; studies report a low recurrence rate of 6% in such cases.

Prognosis and Complications Following Surgical Intervention

Surgical studies highlight a 60% nodular recurrence rate when surgery is pursued for plantar fasciitis, with increased risks associated with bilateral foot involvement, multiple nodules, and a positive family history of the condition. Beyond recurrence, surgical risks encompass impaired wound healing, skin necrosis, painful scarring, nerve entrapment, and potential loss of arch height.

Adjuvant radiotherapy emerges as a preventative measure against fibroma recurrence. Studies suggest that recurrence after excision is rare with adjuvant radiotherapy, with a recurrence rate of less than 50% expected with wide excision and adjuvant radiotherapy. While promising, the rare but significant risks associated with radiation, such as impaired foot function, compromised wound healing, lymphedema, marked fibrosis, irradiated bone fracture, and radiation-induced malignancy, necessitate careful consideration against the potential benefits of recurrence prevention. The decision for surgical intervention, along with adjuvant therapies, should be tailored to individual patient factors and preferences.

Physiotherapy Management for Plantar fibroma

For individuals with plantar fasciitis seeking conservative measures, physiotherapy plays a crucial role. In cases with little or no pain, effective management involves:

- Orthotic Solutions:

Padded shoes with soft insoles or custom-tailored insoles are employed to redistribute weight away from prominent nodules, providing relief and comfort. - Ledderhose Disease Management:

Mild cases of Ledderhose disease benefit from:- Massage using cortisone cream.

- Gentle passive stretching of retracted structures.

- Isometric exercises target toe extensors.

- Symptom relief through padded shoes or tailored insoles

- Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy (ESWT):

ESWT, derived from its success in Peyronie’s disease, softens nodules. The original protocol involves 2000 pulses at 3 Hz frequency, administered at 7-day intervals over 2 weeks. - Post-Surgical Intervention:

Following surgery, a non-weight-bearing phase of 3 weeks is recommended until incision healing occurs. Subsequently, full weight-bearing is allowed. Rehabilitation involves:- Calf Muscle and Plantar Fascia-Specific Stretching: Applied for short-term pain relief and improved flexibility, stretching can be performed 2-3 times a day with sustained or intermittent durations.

- Post-Wound Healing Phase: Involves circulation and scar massage, hot water or paraffin baths with active movements, recovery of joint amplitudes through exercises and postural extension, muscle force recovery through manual techniques, and mechano-therapy appliances.

- Manual Therapy: Limited evidence supports manual therapy for short-term pain relief and improved function. Techniques include anterior and posterior glides of the tarsometatarsal, metatarsalphalangeal, and interphalangeal joints.

- Mobilisation of free articulations.

- Scar tissue massage.

- Lymphatic drainage.

- Pneumatic/air pressure therapy.

- Recovery of joint capsules, cartilage, and toe muscles through passive mobilization, active mobilization, and posture extension.

The comprehensive approach to physiotherapy management aims to alleviate pain, enhance functionality, and contribute to the overall well-being of individuals with plantar fasciitis. For those seeking a deeper understanding, educational resources, such as videos, can provide valuable insights into the condition and its various treatment options.

Conclusion

The best way to treat Plantar Fibroma (PF) is still changing as several established conservative medicines and newer approaches are being investigated, with differing degrees of success. Conservative therapy remains the first choice for symptomatic care because of the benign nature of this illness; nevertheless, there is still a lack of compelling, long-term data supporting its usage.

It will need further investigation to find the best therapy algorithm. Recalcitrant or extremely aggressive instances have a number of surgical procedures available, although nodule recurrence is not unusual.

FAQ

Is plantar fibroma serious?

A benign (nonmalignant) plantar fibroma is a growth that can appear in one or both feet and, in most cases, is not curable or will shrink on its own. Although the exact aetiology of this ailment is unknown, there are a number of therapy options available for plantar fibroma.

How do you get rid of plantar fibromas?

The most popular therapies consist of:

Painkillers are available without a prescription.

Inserts for your shoes are called orthotics.

Stretching.

Verapamil (a cream applied to the plantar surface of the foot)

Cortisone injections.

Can plantar fibroma be cured?

The goal of many plantar fibromas therapies is to reduce the symptoms. These consist of cortisone injections, topical ointments, orthotics, and over-the-counter (OTC) painkillers. However, without therapy, plantar fibromas are unlikely to shrink or go away.

Can you live with plantar fibroma?

The plantar fascia, a band of tissue that runs the length of the foot from heel to toe, contains this nodule imbedded in it. One or both of your feet may develop a plantar fibroma at the same time. Although benign, plantar fibromas require treatment to be removed. This condition’s precise aetiology is unknown.

Who gets plantar fibroma?

Individuals with genetic heritage from northern Europe are more likely to develop plantar fibromas. Foot trauma does not appear to be a contributing factor. Alcohol intake could play a role. Between the epidermis and the initial layers of muscle in the foot’s plantar fascia are where plantar fibromas are found.

Is heat good for plantar fibroma?

In most cases, heat treatment alone is not advised while treating plantar fasciitis. Contrast treatment refers to the use of this medication in conjunction with icing and cold therapies. You will need two foot tubs, one with warm water and the other with icy water, to try the contrast treatment.

What vitamins are good for plantar fibromas?

Supplements like vitamin C and chondroitin encourage the synthesis of collagen, which, when produced in excess, has been connected to the development of fibromas. Diabetes, epilepsy disorders, chronic liver disease, and other medical diseases have all been connected to plantar fibromas.

How long does it take for plantar fibroma to cure?

Healed effectively. Although it may take longer (6–8 weeks), many patients return to shoes after three weeks. After surgery, the foot begins to heal normally, and you can wear shoes again in three to eight weeks. After a long day, the foot could still be somewhat swollen.

How successful is plantar fibroma surgery?

A whole-foot-length incision is used to remove the plantar fascia in its entirety. The most effective method is the more invasive one, which involves a lengthy incision and fascia removal, although there is still a 25% chance of recurrence.

Why do I feel a lump in my foot when I walk?

The most frequent reasons for a sore spot on the ball of your foot are corns, calluses, or warts. Thick patches of skin known as calluses develop when the same area is repeatedly compressed during normal activities.

Do fibromas grow back?

Although it seldom recurs, it can in the event of recurrent trauma in the same location. In less than a year following the surgical removal of the prior lesion, the 13-year-old male patient in this case report experiencing a recurrence of a fibroma in the front area of the hard palate.

Can you remove a fibroma at home?

If you don’t know enough about skin anatomy and adequate sanitization, your efforts are more likely to backfire than to succeed. It might reappear. Unless entirely removed by a skilled surgeon, dermatofibromas are likely to recur, even if you think you have eradicated the bulge. You could inflict a larger and deeper scar.

Reference

- Higuera, Valencia. “What Is a Plantar Fibroma, and How Is It Treated?” Healthline, 13 Apr. 2023, www.healthline.com/health/plantar-fibroma#home-remedies.

- Professional, Cleveland Clinic Medical. “Plantar Fibroma.” Cleveland Clinic, my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/22104-plantar-fibroma. Accessed 27 Nov. 2023.

- “What Is a Plantar Fibroma?” WebMD, 16 Apr. 2021, www.webmd.com/pain-management/what-is-plantar-fibroma.

- Plantar Fibroma – Treatment of Plantar Fibroma | Foot Health Facts – Foot Health Facts. www.foothealthfacts.org/conditions/plantar-fibroma. Accessed 27 Nov. 2023.

- “Plantar Fibromatosis.” Physiopedia, www.physio-pedia.com/Plantar_Fibromatosis. Accessed 27 Nov. 2023.

One Comment