Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury: Physiotherapy Treatment

What is Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury (ACL)?

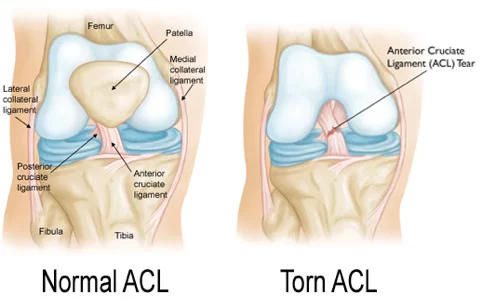

An anterior cruciate ligament injury is a tear in one of the knee ligaments that joins the upper leg bone with the lower leg bone. The ACL keeps the knee stable.

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is one of the four major ligaments that help stabilize the knee. It’s located in the center of the knee, running from the backbone (or femur) to the shin (or tibia), and helps prevent the bones from moving too far apart. ACL injuries are a common sports injury, most often affecting athletes in activities such as football, basketball, and soccer. In most cases, an ACL injury causes a great deal of pain and is difficult to diagnose.

Classification of ACL Injury :

An ACL injury is classified as a grade I, II, or III sprain.

Grade I sprain

The fibers of the ligament are stretched, but there is no tear.

There is a little tenderness and swelling.

The knee does not feel unstable or give out during activity.

Grade II sprain

The fibers of the ligament are partially torn.

There is a little tenderness and moderate swelling.

The joint may feel unstable or give out during activity.

Grade III sprain

The fibers of the ligament are completely torn (ruptured); the ligament itself has torn completely into two parts.

There is tenderness (but not a lot of pain, especially when compared to the seriousness of the injury). There may be a little swelling or a lot of swelling.

The ligament cannot control knee movements. The knee feels unstable or gives out at certain times.

Causes of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury

ACL Ligaments are strong bands of tissue that connect one bone to another. The ACL, one of two ligaments that cross in the middle of the knee, connects your thighbone (femur) to your shinbone (tibia) and helps stabilize your knee joint.

Most ACL injuries happen during sports and fitness activities that can put stress on the knee:

Suddenly slowing down and changing direction (cutting)

Pivoting with your foot firmly planted

Landing from a jump incorrectly

Stopping suddenly

Receiving a direct blow to the knee, such as a football tackle

Risk Factor for anterior cruciate ligament injury

Cutting, pivoting, and single-leg landings.

About 70% of ACL injuries are non-contact injuries that involve sudden deceleration, such as cutting, pivoting, or landing on one leg. They occur most commonly in sports such as basketball, soccer, American football, volleyball, downhill skiing, lacrosse, and tennis.

Female gender.

Females are at 4 to 6 times higher risk than males. In fact, year-round female athletes who play soccer or basketball have a rate of ACL tear of almost 5%.

Previously torn ACL.

Once an ACL tear has occurred, the risk of re-tear of the previously repaired ACL is approximately 15% higher than that of the primary ACL tear.

A direct blow to the outside of the leg or knee.

ACL injuries from contact typically occur from a direct blow to the knee when it is hyper-extended or bent slightly inward (valgum).

Age.

ACL tears are most common between the ages of 15 and 45, mostly due to the more active lifestyle and higher participation in sports

Symptoms of Anterior cruciate ligament injury

Symptoms of an acute ACL injury include:

Feeling or hearing a pop in the knee at the time of injury.

Pain on the outside and back of the knee.

The knee swelling within the first few hours of the injury. This may be a sign of bleeding inside the knee joint. Swelling that occurs suddenly is usually a sign of a serious knee injury.

Limited knee movement because of pain or swelling or both.

The knee feels unstable, buckling, or giving out.

The knee may feel warm to the touch, due to bleeding within the knee joint

After an acute injury, you will probably have to stop whatever you are doing because of the pain, but you may be able to walk.

The main symptom of chronic ACL deficiency is the knee buckling or giving out, sometimes with pain and swelling. This can happen when an ACL injury is not treated.

Diagnosis of ACL injury

Your doctor can tell whether you have an ACL injury by asking questions about your past health and examining your knee. The doctor may ask: How did you injure your knee? Have you had any other knee injuries? Your doctor will check for stability, movement, and tenderness in both the injured and uninjured knee.

X-rays, which can show damage to the knee bones.

MRI. An MRI can show damage to ligaments, tendons, muscles, and knee cartilage.

Arthroscopy During arthroscopy, a doctor inserts surgical tools through one or more small cuts (incisions) in the knee to look at the inside of the knee.

Other tests Lachman’s sign is the most accurate ACL injury test. It is performed with the athlete on his or her back with the affected leg relaxed, and the examiner holding the leg with the knee bent at 30 degrees of flexion. With one hand on the thigh for stabilization, a pull forward on the calf will show an increase in motion and soft endpoint compared to the other knee if the ACL is ruptured.

Other tests for the ACL include the pivot-shift and the anterior drawer tests. Caution must be exercised if the examination occurs after significant swelling has occurred because this may reduce their accuracy.

Surgical treatment:

During arthroscopic ACL reconstruction, the surgeon makes several small incisions-usually two or three around the knee. The sterile saline (salt) solution is pumped into the knee through one incision to expand it and to wash the blood from the area. This allows the doctor to see the knee structures more clearly.

The surgeon inserts an arthroscope into one of the other incisions. A camera at the end of the arthroscope transmits pictures from inside the knee to a TV monitor in the operating room.

Surgical drills are inserted through other small incisions. The surgeon drills small holes into the upper and lower leg bones where these bones come close together at the knee joint. The holes form tunnels through which the graft will be anchored.

If you are using your own tissue, the surgeon will make another incision in the knee and take the graft (replacement tissue).

The graft is pulled through the tunnels that were drilled in the upper and lower leg bones. The surgeon secures the graft with hardware such as screws or staples and will close the incisions with stitches or tape. The knee is bandaged, and you are taken to the recovery room for 2 to 3 hours.

During ACL surgery, the surgeon may repair other injured parts of the knee as well, such as menisci, other knee ligaments, cartilage, or broken bones.

Physiotherapy Treatment of ACL Injury :

Pre-operative Management :

1. Immobilization: Rest, ice, compression, and elevation.

2. To relieve Pain and Swelling: Icing, TENS / IFT / Ultrasound Therapy

3. Restored range of motion: heel slides, knee flexion and prone knee hang, ankle mobility.

4. Mentally prepare: The patient must know what to expect from the surgery and understand the rehabilitation phases after surgery.

Pre-op. therapy should encourage the strengthening of the quadriceps and hamstrings. Range of motion exercises should be included if there is no pain involved.

Post-operative Management:

Phase 1: 0-2 week

Goals– • Protect graft fixation.

• Minimise effects of immobilization.

• Control inflammation.

• No CPM.

• Achieve full extension, 90 degrees of knee flexion.

• Educate patients about rehabilitation progress.

Brace- • Locked in extension for ambulation & sleeping

Weight-bearing–

• Weight bearing with 2 crutches.

• Discontinue crutches as tolerated after 7 days.

Therapeutic exercises

• Heel slides/wall slides.

• Quadriceps and hamstrings Isometrics

• Patellar mobilisation.

• Non-weight bearing gastroc soleus, hamstring stretches.

• Sitting-assisted flexion hangs.

• Prone leg hangs for an extension.

• Straight leg raises(SLR) in all planes with braces in full extension until quadriceps strength is sufficient to prevent extension lag.

Phase2:- 2-4week

Goals- • Restore normal gait.

• Restore full ROM.

• Protect graft fixation.

• Improve strength and endurance

Weight-bearing

• Patellar tendon graft- continue ambulation with brace locked in extension.

• Hamstring graft and allograft- may discontinue brace use when normal gait pattern and quadriceps control are achieved.

Therapeutic exercises

• Mini-squats 0-30 degrees.

• Closed chain extension (leg press 0-30 degrees).

• Toe raises.

• Continue hamstring stretches and progress to weight-bearing gastro soleus stretches.

• Continue prone leg hangs with progressively heavier ankle weights until full extension is achieved.

Phase3:- 5-12 week

Goals- • Improve confidence in the knee.

• Avoid overstretching graft fixation.

• Protect the patellofemoral joint.

• Progress strength.

Therapeutic exercises

• Continue flexibility exercises as appropriate for a patient.

• Advanced closed kinetic chain strengthening (one leg squat, leg press 0-60 degrees).

• Elliptical stepper, stair stepper.

Phase4:- 12-20week

Goals– • Return to unrestricted activities.

Continue to control swelling.

Regain full movement of the knee.

Continue to improve quads and hamstrings strength.

Start jogging and progress in speed straight line only.

Therapeutic Exercises

Continue and progress flexibility and strengthing programs

Hopping single leg.

Double-leg jumps.

Jogging – start slowly and ensure there is no limp before going quicker.

Increase running speed slowly and progressively over a period of weeks BUT ONLY IN STRAIGHT LINES WITH NO TURNING.

If any of the exercises above are painful during or after performing them then stop immediately.

Phase5:-after 20 week

Goal– Introduce ball work (if required).

Continue to improve balance around the knee.

Achieve at least 90% strength in the quads and hamstrings in comparison to the other uninjured leg.

Improving confidence.

Therapeutic Exercises:

Exercises that are typically introduced at this stage, in addition to the previous stage’s exercises are;

Box Jumps

Start to gradually introduce twisting and turning movements.

Start to introduce striking a ball (if required).

Start to perform functional sports-specific drills.

14 Comments