Deltoid Muscle Atrophy

What is a Deltoid Muscle Atrophy?

Deltoid Muscle Atrophy refers to the wasting or loss of muscle mass and strength in this particular muscle group. This condition can arise due to various underlying factors, such as disuse, neurological disorders, or specific injuries, leading to a reduction in muscle size and function.

Understanding the causes, symptoms, and potential treatments for deltoid muscle atrophy is essential for effectively managing and addressing this muscular condition.

Overview

A thick, triangular shoulder muscle is called the deltoid. Its resemblance in shape to the Greek letter “delta” (Δ) gives it its name. The origin of the muscle is broad and extends to the clavicle, acromion, and scapular spine. It enters onto the humerus after passing inferiorly around the glenohumeral joint on all sides.

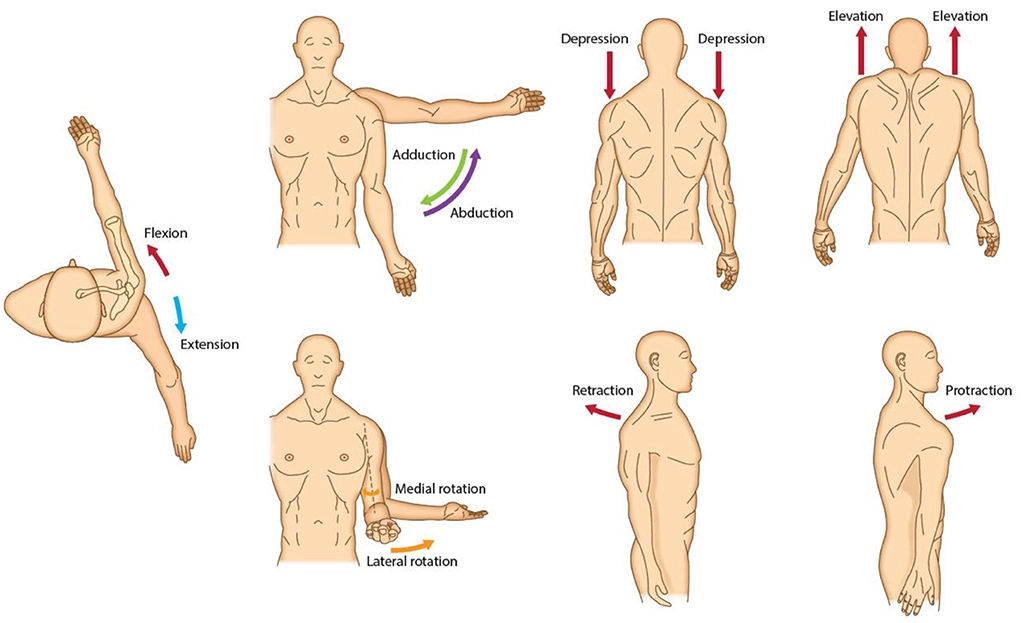

The acromial, clavicular, and scapular spinal segments combine to produce the deltoid. While the clavicular and scapular spinal segments are important for stabilization and maintaining a stable plane of abduction, the acromial section (middle fibers) is responsible for the abduction of the arm.

Furthermore, the scapular spinal component (posterior fibers) can extend and rotate the arm externally, whereas the clavicular component (anterior fibers) can function as an internal rotator and flexor of the arm.

Origins and Insertion

The deltoid muscle is triangular in shape because of its wide origin and narrow base. Each of the deltoid’s three components has a distinct origin:

- The acromial (middle) part comes from the lateral margin and superior surface of the acromion of the scapula.

- The clavicular (anterior) section begins from the superior surface and the anterior border of the lateral third of the clavicle.

- The lateral third of the scapula’s spine, on the crest, is where the scapular spinal (posterior) portion begins.

- Use this easy mnemonic to help you recall the three deltoid origins!

Deltoid assists with carrying SACS:

- Spine of Sacrum

- Acromion

- Clavicle

After that, the muscle fibers converge to a narrow, powerful tendon as they run inferiorly toward the humeral shaft. It inserts into the deltoid tuberosity, which is situated about midway down the lateral part of the humerus shaft.

Innervation

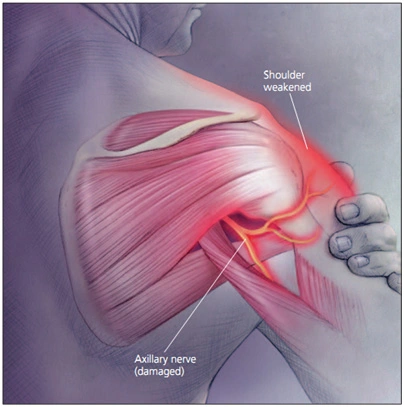

One of the primary branches of the brachial plexus, the axillary nerve (C5, C6), innervates the deltoid muscle.

Blood supply

The deltoid muscle has a substantial circulatory supply from a variety of sources due to its size:

- Subscapular artery;

- Anterior circumflex humeral artery;

- Posterior circumflex humeral artery;

- Thoracoacromial artery (acromial and deltoid branches);

- Deep brachial artery (deltoid branch)

With the exception of the profunda brachii, a branch of the brachial artery—the axillary artery’s continuation within the arm—all arteries supplying the deltoid are branches of the axillary artery.

Function

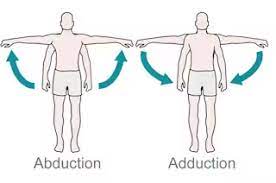

At the glenohumeral joint, the primary arm abductor is the deltoid muscle (acromial part). But only if the arm has already been lowered more than fifteen degrees can it do so. The muscle that produces this first portion of abduction is the supraspinatus. During the abduction motion, the arm is guided by the muscle’s clavicular and scapular spinal fibers.

The deltoid muscle helps to stabilize the glenohumeral joint along with the rotator cuff muscles. Static contraction occurs when a muscle produces a line of force to prevent inferior displacement of the glenohumeral joint when carrying heavy objects while the arm is fully adducted. When the arm is lowered, or adducted, the deltoid muscle also experiences an eccentric contraction. This makes controlled arm adduction possible.

When walking or running, the pectoralis major and the clavicular (anterior) fibers of the deltoid muscle work together to cause the arm to flex. When the humerus rotates internally, or medially, these fibers are also active.

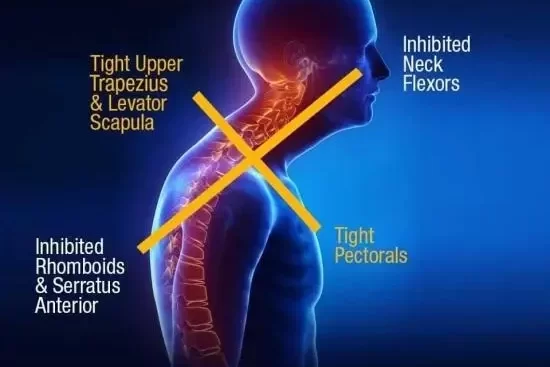

During walking, the latissimus dorsi and the scapular spinal (posterior) fibers of the deltoid produce arm extension, in contrast to the anterior fibers. Furthermore, these fibers will support the humerus’s lateral, or external, rotation. This is significant from a functional perspective because it can counteract the tendency of the shoulder to become internally rotated as a result of bad posture by strengthening the posterior fibers of the deltoid muscle.

Causes of Deltoid Muscle Atrophy

An example of peripheral neuropathy is the malfunctioning of the axillary nerves. It happens when the axillary nerve is injured. This nerve aids in controlling the skin surrounding the shoulder and the deltoid muscles. A mononeuritis is an issue affecting a single nerve, such as the axillary nerve.

The following are the typical causes:

- Direct damage;

- Entrapment by neighboring bodily structures;

- Long-term strain on the nerve;

- Shoulder injury

The nerve is compressed when it travels through a small opening due to entrapment.

The myelin sheath covering the nerve or a portion of the nerve cell (the axon) may be completely destroyed by the injury. Any kind of damage limits or stops impulses from passing through the nerve.

- Axillary nerve injury

The axillary nerve circles the surgical neck of the humerus as it travels posteriorly via the axilla. Therefore, fractures in this area of the humerus may impact nerve function, which in turn may impact the deltoid muscle. Furthermore, the axillary nerve may sustain damage from a glenohumeral joint dislocation or from being squeezed during improper crutch use.

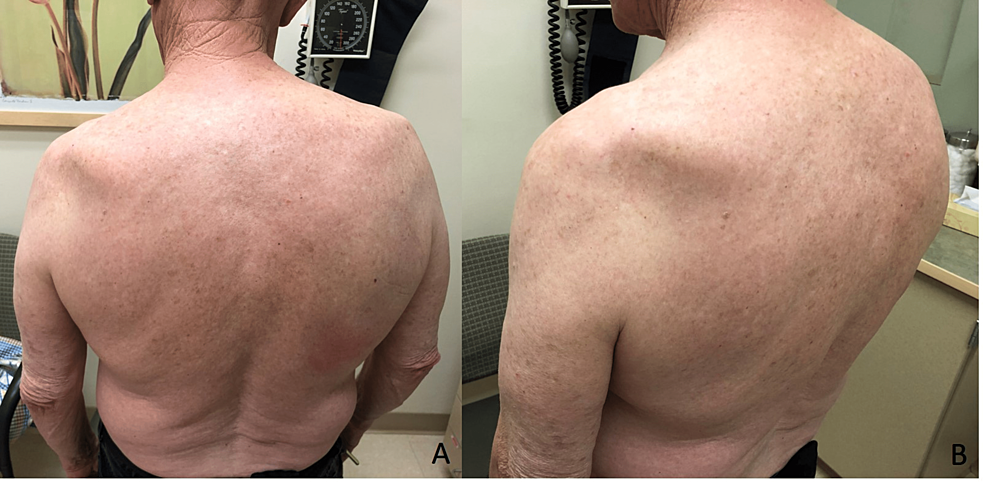

The deltoid muscle atrophy, which causes weakness and a loss of muscle tone and gives the shoulder a flattened rather than rounded appearance, is one of the possible symptoms. Additionally, the skin covering the deltoid muscle may become devoid of feeling.

In order to prevent injury to the axillary nerve, it is also crucial to understand its placement anteriorly while administering intramuscular injections in the deltoid muscle and when performing shoulder surgery.

- Subacromial/subdeltoid bursitis

Injuries affecting the glenohumeral joint’s supporting muscles and other structures may be indicated by deltoid pain. Nestled between the supraspinatus tendon and the acromion, deep within the deltoid muscle, is the subacromial/subdeltoid bursa.

The larger tubercle of the humerus approaches the acromion during overhead arm motions, particularly when the arm is internally rotated. Pinching the subacromial/subdeltoid bursa between the acromion and greater tubercle of the humerus repeatedly can cause it to swell and become inflamed. Then, under the deltoid muscle, the bursa may swell and become painful.

Axillary nerve dysfunction can result from the following conditions:

- Deep infection;

- Upper arm bone (humerus) fracture

- Pressure from casts or splints

- Improper use of crutches

- Systemic illnesses that induce nerve inflammation throughout the body

- Shoulder dislocation. Sometimes there is no apparent reason.

Symptoms of Deltoid Muscle Atrophy

The following symptoms could be present:

- Numbness over a portion of the outer shoulder;

- Pain in the shoulder region;

- Shoulder weakness, especially while moving the arm up and away from the body;

- Numbness across a portion of the outer shoulder;

- Pain in the shoulder region

Diagnosis

Examine and assess

Your physician will check your shoulder, arm, and neck. Your arm may become difficult to move if you have shoulder weakness. Muscular atrophy, or the thinning and loss of muscular tissue, can manifest in the deltoid muscle of the shoulder.

MRI or X-rays of the shoulder are among the tests that may be used to check for axillary nerve dysfunction. EMG and nerve conduction tests should be performed several weeks after the injury or the onset of symptoms, and they are likely to be normal immediately after the injury.

- Muscle testing

To accurately diagnose muscular or nervous system injury, it is crucial to perform a proper function test on the deltoid muscle. It is not a sign of a deltoid muscle or axillary nerve injury when the arm cannot be abducted from a resting position at the side of the body. It would be indicative of a problem with the supraspinatus muscle or the suprascapular nerve, which innervates it if the arm could not be brought into abduction up to about 15 degrees.

The arm needs to be extended beyond 15 degrees of abduction in order to accurately assess the deltoid and axillary nerve function. After positioning the arm in this manner, the patient presses against any resistance. When a muscle contracts appropriately, it should be felt close to the scapula’s acromion.

Treatment of Deltoid Muscle Atrophy

Some persons with nerve disorders may not require therapy, depending on the underlying reason. The issue might resolve itself. Everybody recovers at a different pace. Recuperation can take many months.

You might receive anti-inflammatory medication if you have any of the following conditions:

- Abrupt symptoms

- Minor alterations in mobility or sensation

- No prior injuries to the region

- No indications of nerve damage

These medications lessen nerve pressure and edema. They can be ingested or injected straight into the affected area.

Additional medications include:

- Painkillers available over-the-counter (OTC) may be useful for moderate pain;

- Painkillers for neuralgia (strangling pain) may assist in lessening discomfort; and

- Opioid painkillers may be required to manage severe pain.

Should your symptoms persist or worsen, surgery might be required. If your symptoms are being caused by a trapped nerve, you might feel better after surgery to release the nerve.

Maintaining muscle strength can be aided by physical therapy. Other forms of therapy, such as muscle retraining or job adjustments, could be suggested.

Physiotherapy Treatment

Exercise

You may build your deltoid muscle by performing a variety of workouts. Among the instances are:

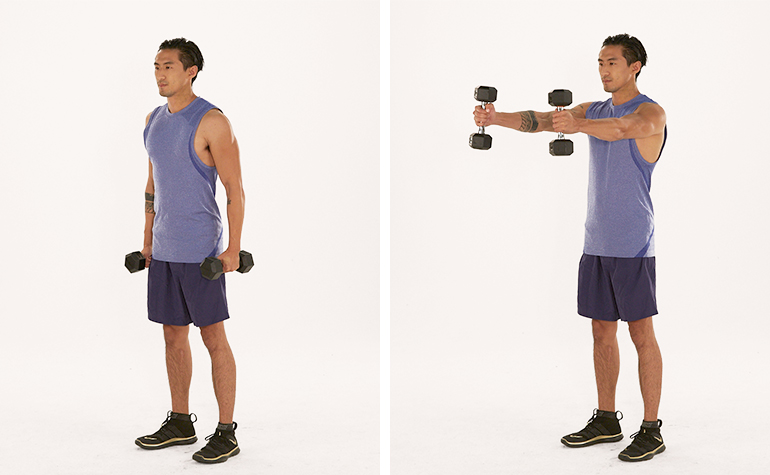

- Abduction of the shoulder: Stretch your arm out to the side until it is parallel to the floor. After holding for a short while, carefully drop your arm.10–15 times over, repeat.

- External rotation of the shoulder: Bend your arm at the elbow and keep your forearm parallel to the floor while you rotate your arm outward until your elbow points upward. After holding for a short while, carefully drop your arm.10–15 times over, repeat.

- Front rise: Place your palms facing forward while holding two little weights in your hands. Lift your arms above your head until they are parallel to the floor. After a brief period of holding, gradually lower your arms.10–15 times over, repeat.

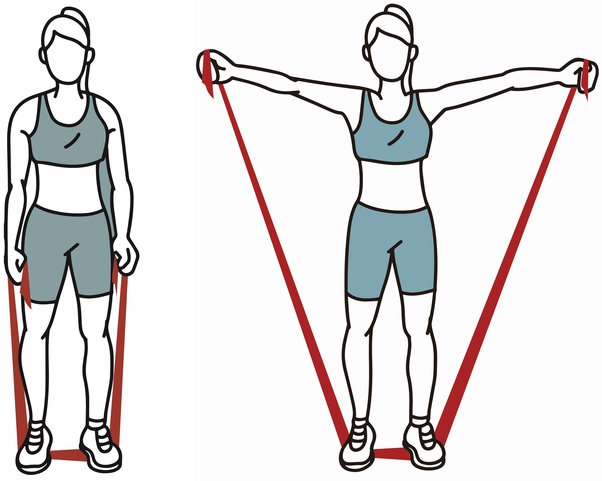

Resistance bands are another tool you may use to build up your deltoid muscle. A variety of exercises can be performed with resistance bands, such as:

The band pull-apart exercise involves holding a resistance band in each hand and extending your arms out to the sides. Pull the bands apart gradually until a “Y” shape is formed. Release the bands gradually after a few seconds of holding.10–15 times over, repeat.

One way to achieve band external rotation is to wrap a resistance band around a doorknob or another robust item. Assume a standing position where your forearm is parallel to the floor and your elbow is bent. With the band end grasped in your palm, extend your arm outside until your elbow points upward. After holding for a short while, carefully drop your arm.10–15 times over, repeat.

When you get stronger, it’s crucial to start off cautiously and progressively increase the duration and intensity of your workouts. Always remember to warm up before working out and cool down afterward.

Supine active assisted:

Place a pillow under your head and lie flat on your back. Extend your elbow to its maximum potential.

Supine active aided. Next, lift your arm to a vertical 90-degree angle, using assistance from your stronger arm if needed. You can straighten your elbow once you’ve reached ninety degrees.

Use its own strength to maintain your arm in this upright posture. Rotate your arm slowly in small clockwise and counterclockwise circles by keeping your fingers, wrist, and elbow straight. Increase the circle by small increments until it feels comfortable (it can take a few weeks to go to larger and larger circles). Second, gently move the arm in an erect position from both sides by moving it forward and backward in line with the outside leg.

Continue moving fluidly and continuously for five minutes, or until you become tired. Gradually extend the range of motion of your shoulder until it can go from the side of your thigh up above your head, contacting the bed, and back as you gain more confidence in your ability to control it. Advance to lightweight:

Progress to lightweight:

A Lightweight object, such as a tiny paperweight or tin of beans, should be held in the afflicted hand as you gain more confidence in your ability to regulate your shoulder movement.

Progress to sitting and standing:

Steps to take in moving from lying down to sitting and finally standing include:

1. Gaining more self-assurance in your ability to manage your shoulder movement.

2. At this point, you can either raise the head of your bed or place pillows beneath your back to take a more reclining posture.

3. Carry out the identical drill once more, but this time defying gravity.

4. Restart by using your arm’s inherent strength to hold it upright this time.

5. Carry out steps 5 through 7 as before.

6. Begin with no weights at all and work your way up to using the same lightweight while lying down.

Resisted exercise:

1. To retrain the deltoid muscle’s concentric contracture through resisted exercise.

2. Using the hand on the affected side, form a fist. The opposite side’s flat hand is acting as resistance. Push the hand on your afflicted side against the other’s resistance. You’ll notice that you can raise your arm above your head to its maximum height while doing this.

3. Carry out these drills repeatedly to “train” and retrain your Deltoid muscle to execute this “concentric contracture” even in the absence of pushing on your opposing arm.

Firstly, the following fundamental exercise for strengthening the deltoid should be done two or three times a day, as long as it doesn’t hurt more.

The exercise can be advanced as your deltoid strength increases by progressively upping the repetitions and contraction force, as long as it doesn’t worsen or create pain.

Deltoid Contraction in Static

Start the deltoid strengthening exercise by standing close to a wall with your back straight and your elbows bent. Push your arm as gently as possible against the wall, using as much pressure as is comfortable but not painful. As long as there is no pain, hold for five seconds and repeat ten times on each side.

Deltoid Strengthening – Intermediate Deltoid Exercises

Deltoid workouts can be advanced as your strength increases, as long as they don’t aggravate existing pain. You can accomplish this by progressively increasing the number of sets, repetitions, or resistance.

The following intermediate deltoid strengthening exercises should typically be done once to three times per week, providing they do not cause or exacerbate pain. For the sake of muscle recovery, it is best not to execute them back-to-back days. The workouts for your deltoid muscles can be advanced as your strength increases, as long as it doesn’t hurt more or create discomfort. You can accomplish this by progressively increasing the repetitions, sets, or resistance.

Resistance Band Forward Raises.

Start this exercise by standing with your back straight and a resistance band in your hands, as shown. Maintaining a straight back and arm, slowly lift your arm to shoulder level. back down gradually after that. If the exercise causes you any pain, complete three sets of ten repetitions.

The resistance Band Side Raises.

Side Raises using Resistance Bands

Start this exercise by standing with your back straight and a resistance band in your hands. While maintaining a straight back and arm as illustrated, slowly lift your arm to the side until it is level with your shoulder. back down gradually after that. As long as the exercise is pain-free, complete three sets of ten repetitions.

Pull-backs with resistance bands

Starting from a standing position, maintain a straight back while grasping a resistance band as modeled. Steadily raise your arm to the side while maintaining a straight elbow and back. then make your way back to the starting position carefully. As long as the exercise is pain-free, complete three sets of ten repetitions.

Prognosis

If the source of the Deltoid muscle atrophy is found and effectively treated, a full recovery might be achievable.

Potential Difficulties

The following complications could arise:

- Arm deformity, or shoulder contracture, or frozen shoulder;

- Rarely, partial arm loss of sensation

- Partial shoulder paralysis

- Repeated arm injuries

When to Speak with a Medical Expert

If you are experiencing signs of Deltoid muscular atrophy, schedule an appointment with your practitioner. The likelihood of symptom management increases with early identification and therapy.

Prevention

Depending on the cause, different preventive actions apply. Refrain from applying prolonged pressure to the area under your arms. Verify that equipment such as splints and casts fit correctly. Learn to keep your underarms free of pressure when using crutches.

Summary

Deltoid muscle atrophy involves the wasting or loss of muscle mass and strength in the deltoid muscle, situated in the shoulder. Comprising anterior, middle, and posterior fibers, the deltoid enables crucial arm movements. Atrophy can result from causes such as disuse, neurological disorders, or specific injuries, leading to reduced muscle size and function.

A comprehensive understanding of the underlying factors, symptoms, and potential treatments is crucial for managing this condition effectively.

FAQs

What is the atrophy of the muscles?

Loss of muscle tissue is known as muscular atrophy. There are other synonyms for muscular atrophy as well, such as muscle catabolism, muscle loss, muscle wasting, and muscle withering.

Why does muscular atrophy occur?

Many factors can lead to muscle atrophy. Muscles that are not used can generally weaken and shrink. One reason is a deficiency of exercise. Atrophies can also result from nerve injury. Muscle atrophy can also be brought on by malnutrition, aging, prolonged corticosteroid use, and a variety of medical disorders.

Is it possible to restore muscles that have atrophy?

Indeed, it is possible to regenerate muscles that have atrophy. Combining physical activity with strengthening exercises and eating a healthy diet can often be beneficial.

References

- BSc, E. P. (2023, October 30). Deltoid muscle. Kenhub. https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/the-deltoid-muscle

- Axillary nerve dysfunction: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. (n.d.). https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/000689.htm

- Eustice, C. (2022, March 31). Muscle Atrophy Types and Causes. Verywell Health. https://www.verywellhealth.com/what-is-muscle-atrophy-2552171

2 Comments