Hip Joint: Anatomy, Movement, Function, Importance

Introduction

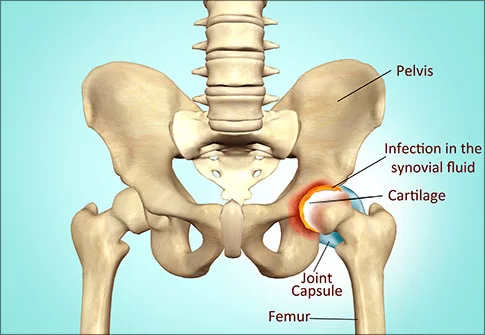

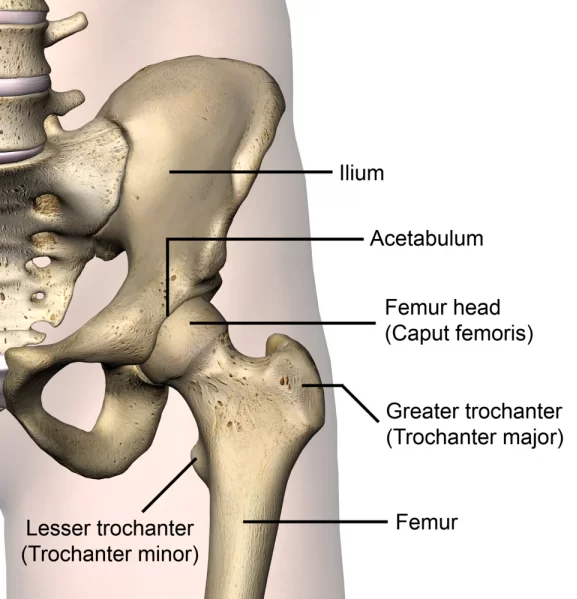

The hip joint is the largest and most complex joint of the human body. The hip joint is a ball and socket joint. The hip ball is known as the femoral head and the socket is called acetabulum. The femoral head is made up of three layers of tissue (bone, cartilage, and soft tissue).

Hip Joint Anatomy is the study of the hip joint. The hip joint is the articulation between the femur and the acetabulum of the pelvis. The hip joint is a ball and socket joint and allows for a large range of motion than any other joint in the body. Studies show that about 1 in 3 adults suffer from hip pain, and other studies show that 10% of people will need surgery to replace their hip joints.

The hip is a true diarthroidal ball-and-socket style joint, formed from the head of the femur as it articulates with the acetabulum of the pelvis. This joint serves as the main connection between the lower extremity and the trunk and typically works in a closed kinematic chain.

Hip joint anatomy is divided into four main categories: acetabulum, femur, ilium, and pubis.

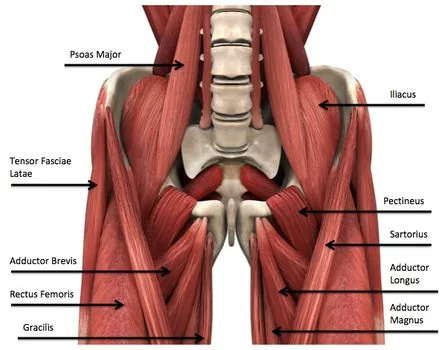

Muscles Around Hip Joint

The hip joint is one of the most flexible joints in the entire human body. The many muscles of the hip provide movement, strength, and stability to the hip joint and the bones of the hip and thigh. These muscles can be grouped based on their location and function. The four groups are the anterior group, the posterior group, the adductor group, and finally the abductor group.

The anterior muscle group features muscles that flex (bend) the thigh at the hip

(1) Gluteal muscles Group

The gluteal muscles cover the lateral surface of the ilium and include

- Gluteus maximus

- Gluteus medius

- Gluteus minimus

- Tensor fasciae latae

(2) Adductor group

This group includes

- Adductor brevis

- Adductor longus

- Adductor magnus

- Pectineus

- Gracilis

The adductors all originate on the pubis and insert on the medial, posterior surface of the femur, with the exception of the gracilis which inserts just below the medial condyle of the tibia.

(3) Iliopsoas group :

The iliacus and psoas major comprise the iliopsoas muscle group.

(4)Lateral rotator group

This group consists of

- Obutrator externus

- Obturator internus

- Piriformis muscle

- Superior and inferior gemelli

- Quadratus femoris.

These six originate at or below the acetabulum of the ilium and insert on or near the greater trochanter of the femur.

Other Hip muscles:

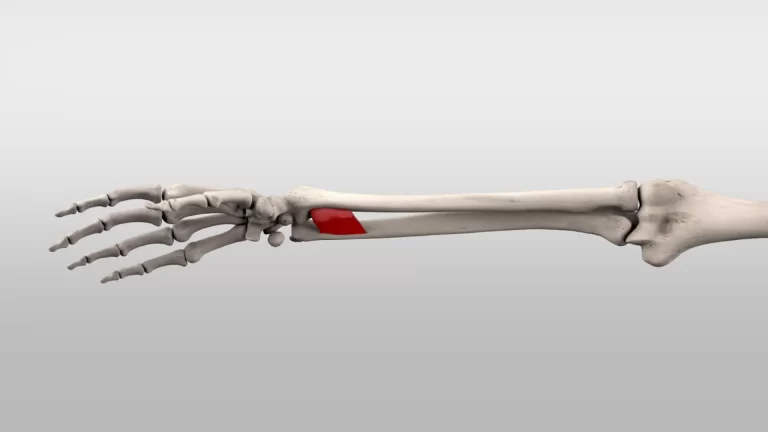

Rectus femoris and the sartorius, can cause some movement in the hip joint but these muscles primarily move the knee, and are not generally classified as muscles of the hip.

The hamstring muscles, which originate mostly from the ischial tuberosity and insert on the tibia/fibula, also assist with hip extension.

Embryology

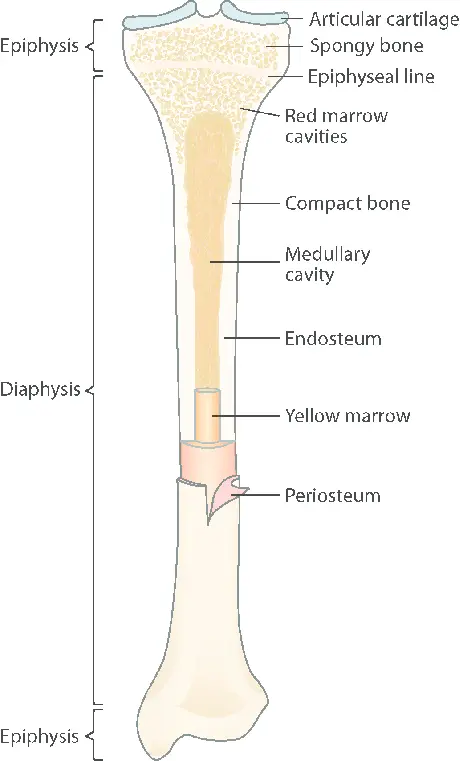

By weeks 4 to 6 of gestation, mesoderm starts to form the hip joint. Precartilage cells that will later develop into the femoral head and acetabulum have a cleft by seven weeks of gestation. The hip joint has largely developed by 11 weeks of gestation. The femoral head is entirely encircled by the acetabular cartilage.

Blood Supply

The hip’s blood flow is subject to a wide range of alterations. The medial circumflex and lateral circumflex femoral arteries, each of which is a branch of the profunda femoris (deep artery of the thigh), supply blood in the most typical variation. A posteriorly moving branch of the femoral artery is called the profunda femoris.

The foveal artery, also known as the artery to the head of the femur, is a branch of the posterior division of the obturator artery that passes through the head of the femur ligament and contributes extra. When the medial and lateral circumflex arteries are disrupted, avascular necrosis can be prevented by the foveal artery.

A pair of interesting anastomoses exist. The trochanteric anastomosis supports the head of the femur, and the cruciate anastomosis supports the upper thigh.

Lymphatics Drainage

The internal iliac nodes receive lymphatic drainage from the medial and posterior aspects, and the deep inguinal nodes receive lymphatic drainage from the anterior aspect.

Nerves Supply

The superior gluteal, obturator, and femoral nerves innervate the hip joint.

Ligaments of Hip Joint:

As noted above, the stability of the hip joint is directly related to its muscles and ligaments. The most notable ligaments in the hip joint are:

Iliofemoral ligament, which connects the pelvis to the femur at the front of the joint. It keeps the hip from hyper-extension

Pubofemoral ligament, which attaches the most forward part of the pelvis known as the pubis to the femur

Ischiofemoral ligament, which attaches to the ischium (the lowest part of the pelvis) and between the two trochanters of the femur.

* Labrum

The labrum is a circular layer of cartilage that surrounds the outer part of the acetabulum effectively making the socket deeper to provide more stability for the joint. Labrum tears are not an uncommon hip injury.

Movement of Hip Joint (Motions Available):

- Flexion: forward and upward movement of the femur at the hip occurs in the sagittal plane about the medial-lateral axis.

- Extension: upward movement toward the rear of the body of the femur at the hip occurring in the sagittal plane.

- Abduction: movement of the femur on the hip in a direction away from the midline of the body in the frontal plane.

- Adduction: movement of the femur on the hip in a direction toward the midline of the body in the frontal plane.

- Internal Rotation: rotation of the femur toward the midline of the body in the transverse plane.

- External Rotation: rotation of the femur away from the midline of the body in the transverse plane.

Hip joint-related disorders:

Hip disorders are often due to developmental conditions, injuries, chronic conditions, or infections.

(1) Osteoarthritis of Hip Joint

Degeneration of cartilage in the joint causes osteoarthritis of Hip. This makes the cartilage split and become brittle. In some cases, pieces of the cartilage break off in the hip joint. Once the cartilage wears down enough, it fails to cushion the hip bones, causing pain and inflammation.

(2) Developmental Dysplasia

This condition occurs when a newborn baby has a dislocated hip or a hip that easily dislocates. A shallow hip socket that allows the ball to easily slip in and out is the cause of developmental dysplasia.

(3) Perthes Disease

This disease affects children between the ages of 3 and 11. Perthes disease is the result of reduced blood supply to bone cells. This causes some of the bone cells in the femur to die and the bone to lose strength.

(4) Irritable Hip Syndrome

Irritable hip syndrome can be common in children after an upper respiratory infection. It causes hip pain that results in limping. In most cases, it resolves by itself.

(5) Soft Tissue Pain and Referred Pain

Pain in the hip may be due to an injury or defect affecting the soft tissues outside of the hip. This is known as referred pain.

(6) Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis

A slipped capital femoral epiphysis is a separation of the ball of the hip joint from the thigh bone (femur) at the upper growing end (growth plate) of the bone. This is only seen in growing children. Surgically stabilizing the joint with pins is a common effective treatment.

Hip Strengthening exercise

Basic Exercises

To begin with, the following basic hip strengthening exercises should be performed approximately 10 times, 3 times daily. As your hip strength improves, the exercises can be progressed by gradually increasing the repetitions and strength of contraction provided they do not cause or increase pain.

(1) Bridging

Begin this exercise lying on your back and Slowly lift your bottom pushing through your feet, until your knee, hip, and shoulder are in a straight line. Tighten your bottom muscles (gluteals) as you do this. Hold for 2 seconds and repeat 10 times.

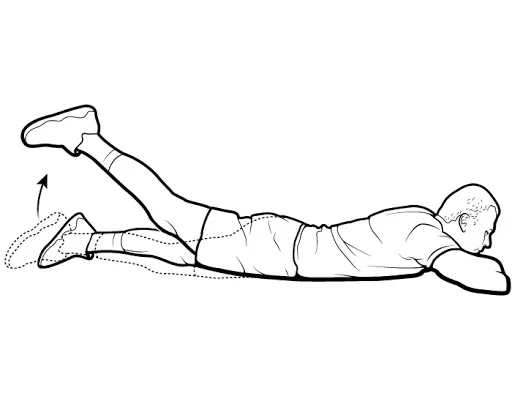

(2) Hip Extension in Lying

Begin this exercise prone lying position on your stomach Keeping your knee straight, slowly lift your leg tightening your bottom muscles (gluteals). Hold for 2 seconds and repeat 10 times.

(3) Adductor Squeeze

Begin this exercise lying and rolled a towel or ball between your knees Slowly squeeze the ball between your knees tightening your inner thigh muscles (adductors). Hold for 5 seconds and repeat 10 times as hard as possible pain-free.

Surgical Considerations

Patients experiencing hip pain due to degenerative conditions may choose to undergo total hip arthroplasty (THA) as an elective procedure. THA is a very successful procedure that enhances quality of life by reducing pain and restoring function. Patients who have not responded to other conservative measures, such as corticosteroid injections, physical therapy, weight loss, or prior surgical procedures, should consider total hip arthroscopy (THA).

Approaches

For the THA procedure, surgeons have a plethora of strategies at their disposal. The following are the three most widely used methods:

Posterolateral

The most popular method for treating primary and revision THA cases is this one. The internervous plane is not used in this dissection. The gluteus maximus fibers are bluntly dissected during the intermuscular interval, and the fascia lata is sharply incised distally. The short external rotators and capsule are meticulously dissected during the deep dissection. When these structures are eventually restored via trans-osseous tunnels back to the proximal femur, caution must be taken to preserve them.

The avoidance of hip abductors is a major benefit of this strategy. Additional advantages include the femur’s and acetabulum’s excellent exposure as well as the option for extensile conversion in either the proximal or distal direction. Higher dislocation rates have been reported in the past in studies that contrasted this method with the direct anterior (DA) approach.

Because there hasn’t been a clear consensus in the literature regarding this data, particularly when comparing posterior approach techniques that use optimal soft tissue repair at the end of THA procedures, the results are still unclear and contentious.

Direct Anterior (DA)

THA surgeons are increasingly adopting the DA approach. The internervous interval is located between the gluteus medius and rectus femoris (RF) on the deep side and the tensor fascia lata (TFL) and sartorius on the superficial end. Advocates of DA THA point to the potential reduction in hip dislocation rates following surgery as well as the avoidance of the hip abduction muscles.

Among the drawbacks is the approach’s learning curve, since the literature shows that complication rates drop once a surgeon completes more than 100 cases. Increased wound complications, challenging femoral exposure, the possibility of lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN) paresthesias, and a possible increased incidence of intra-operative femur fractures are some additional drawbacks.

Lastly, a lot of surgeons require access to a specialized operating table along with surgical technicians and staff who are properly trained to help with the procedure. Learning to perform the procedure on a standard operating table also entails a significant learning curve, though it’s not always required.

Anterolateral

Because it violates the hip abductor mechanism, the anterolateral (AL) approach is the least used in comparison to the other approaches. The gluteus medius and TFL musculature are among the intervals that are exploited; as a tradeoff for a potentially lower dislocation rate, this could result in a postoperative limp.

Conclusion

One of the most vital parts of your body is your hip joint. It aids in maintaining your body’s equilibrium while you move and walk. By exercising and stretching your muscles before you begin any activity, you can maintain the health of your hip joints. Avoid pushing yourself beyond what your body is capable of handling. You can learn how to maintain the health of your hip joints from a healthcare professional.

FAQs

What is the full name of the hip joint?

The main purpose of the hip joint, also known as the acetabulofemoral joint (art. coxae) in science, is to support the body’s weight in both static (like standing) and dynamic (like walking or running) postures.

Why is the hip joint important?

During stance and gait, the hip functions as a multi-axial ball-and-socket joint that provides stability for the upper body. The hip joint’s stability and balance permit motion while supporting the forces involved in daily activities.

What are the 2 hip bones?

It is composed of the femur, or thigh bone, and the pelvis, which consists of the ischium, pubis, and ilium bones.

What is the type of hip joint?

A ball and socket joint makes up your hip joint. The femur is a long bone that ends in a rounded point. The acetabulum, a cup-shaped socket in your pelvis, is where the round end of your femur rests. This kind of joint gives you a lot of range of motion and helps your legs support your body.

What is your strongest joint?

The largest and strongest joint in the human body is the hip joint.

It is constantly in use. Overuse of a joint causes it to begin recruiting surrounding muscles, ligaments, and tendons as a kind of compensation.

Degeneration/ Osteoarthritis (OA)

Femoroacetabular Impingement (FAI)

References

- Gold, M. (2023, July 25). Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Hip Joint. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470555/

- Professional, C. C. M. (n.d.). Hip Joint. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/24675-hip-joint

29 Comments