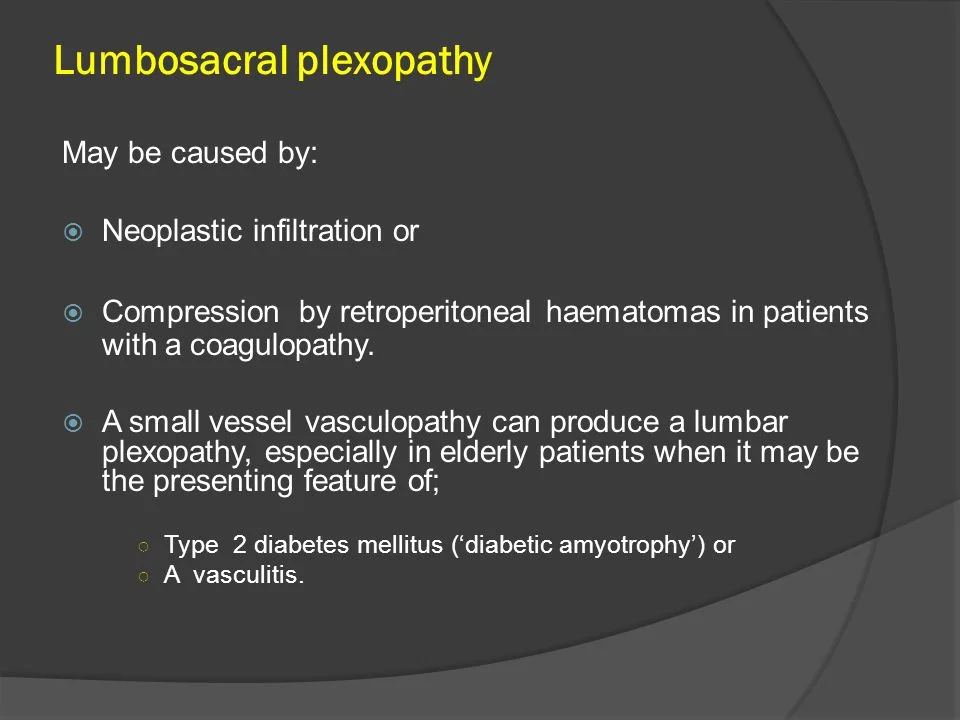

Lumbosacral plexopathy

Introduction

- Lumbosacral plexopathy is a relatively rare occurrence that can be difficult to diagnose & manage. When an injury happens to the lumbosacral plexus, patients predominantly feel pain. This activity outlines the evaluation, & treatment of lumbosacral plexopathy, & highlights the role of the interprofessional team in improving care for patients with this condition.

- The lumbosacral (LS) plexus is a network of nerves organized by the anterior rami of the lumbar & sacral spinal cord. It is an injury to the nerves in the lumbar &/or sacral plexus. LS plexopathy is not a rare condition but can be difficult to diagnose & manage. However, it is far less frequent than brachial plexopathy. Patients with Lumbosacral plexopathy usually present with low back &/or leg pain. They can also experience motor weakness, & other sensory symptoms of insensibility, paresthesia, &/or sphincter dysfunction.

- LS plexopathy can be caused by multiple etiologies, with diabetes mellitus, traumatic injury, neoplasms, & pregnancy being a few of the important causes. Treatment is often limited & varies significantly depending on the underlying pathology.LS plexopathy can be debilitating, severely affecting a patient’s quality of life. Early identification & management are critical in reducing morbidity & mortality.

Causes of Lumbosacral plexopathy

- A firm understanding of anatomy is indispensable in understanding the causes & pathophysiology of Lumbosacral plexopathy. The Lumbosacral plexus is a combination of lumbar & sacral plexuses & encompasses the anterior rami of the L1 through S4 nerve roots of the peripheral nervous system, with a small contribution from T12 as well. The lumbar plexus is situated above the pelvic brim & forms from L1 through L4 nerve roots, while the S1 through S4 nerve roots make up the sacral plexus, which lies below the pelvic brim.

Lumbar Plexus:

- The four anterior rami of the lumbar nerve roots travel down the psoas muscle & divide into an anterior & posterior branch. These branches after giving rise to individual nerves. The femoral nerve is consist of the posterior branches of L2-L4, while the obturator nerves make up of the anterior branches of L2-L4. Other nerves of the lumbar plexus include the iliohypogastric nerve (T12-L1), ilioinguinal nerve (L1), genitofemoral nerve (L1-L2), & lateral femoral cutaneous nerve of the thigh (L2-L3). The sciatic nerve is primarily comprised of anterior & posterior branches of the lumbosacral trunk, as well as the S1 and S2 anterior rami.

- Sacral Plexus: It includes the superior gluteal (L4-S1), inferior gluteal (L5-S2), posterior femoral cutaneous of the thigh (S1-S3), & pudendal nerve (S1-S4). LS plexus receives its blood supply from five lumbar arterial branches of the abdominal aorta. Furthermore, the deep circumflex iliac artery, iliolumbar, & gluteal branches of the internal iliac artery also supply the plexus.

- Direct trauma

- Posterior hip dislocation

- Sacral fracture

- After the lumbar plexus block

- Metabolic, inflammatory, and autoimmune causes: ]

- Diabetes mellitus (DM) – is more common in those with type II DM

- Amyloidosis

- Sarcoidosis

- Infections &local abscess.

- Vertebral osteomyelitis

- Chronic infections (e.g. Tuberculosis, fungal infections)

- Other infections: Lyme disease, HIV/AIDS, Herpes zoster

- Psoas abscess

- Radiation therapy of the abdominal & pelvic malignancies.

- Pregnancy-related

- Mostly happened in the third trimester & after delivery due to birth trauma.

- Postoperative plexopathy

- Scar tissue formation & hematomas may occur following gynecological & other pelvic surgeries.

- Damage to the vasculature innervating the Lumbosacral plexus plexus

- Femoral vessel catheterization

- Ischemia from direct squeezing due to arterial pseudoaneurysms, aortic dissection, retroperitoneal hematoma, etc.).

Epidemiology

- Due to the diverse etiologies, the age of presentation & prevalence varies. However, the median age for diagnosis of Lumbosacral plexopathy is around 65 years for all causes. LS plexopathy is more common in women due to the predisposing risk factors of pregnancy & gynecological cancers.

- The incidence of diabetic amyotrophy is 4.2 per 100,000 annually &occurs in 0.8 percent of people with diabetes mellitus (DM).[14] The median duration of DM is four years with a median hemoglobin A1c of 7.5% at the time of determination of diabetic amyotrophy.

- For neoplastic cases of LS plexopathy, the L4-S1 segment is commonly affected (>50% of cases) followed by the L1-L4 segment (31%), & pan-plexopathy (about 10%).[16] In 73% of cases, a local compression & invasion of an abdominopelvic malignancy was present. Lumbosacral plexopathy takes place within one year of diagnosis in over one-third of patients with primary tumors. In 15% of cases, Lumbosacral plexopathy resulted in the diagnosis of cancer.

- Lumbosacral plexopathy occurs in approximately 0.7% of cases following a traumatic pelvic fracture. Incidence increases to 2% following a sacral fracture.

- Lumbosacral plexopathy occurs in an estimated 1 in 2000-6400 deliveries.

- The occurrence of retroperitoneal hematoma following a femoral artery catheter is only 0.5%. About 20% of these patients develop underlying femoral neuropathy, while 9% develop Lumbosacral plexopathy.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of LS plexopathy differs based on the etiology:

- Trauma – immediate injury or traction on the plexus

- Tumor – immediate infiltration by the tumor or metastasis, intra-neural lymphomatosis, the perineural EXTENT of prostate cancer

- Radiation – This leads to endothelial damage leading to chronic inflammatory cell migration & a state of fibrosis, followed by an irreversible state of microvascular injury & ischemic damage

- Hematoma – Direct compression

- Diabetic & non-diabetic Lumbosacral plexopathies – caused by inflammatory or microvascular changes

History & Physical examination

- A detailed clinical history & physical examination are crucial for the diagnosis of LUMBOSACRAL plexopathy. Patients typically present with low back pain radiating to one side. Pain may be positional, worse in a supine position. Patients with diabetic LUMbosacral plexopathy (diabetic amyotrophy) typically complain of unilateral pain in the proximal thigh. Tingling numbness with Pain may be associated with paresthesias or dysesthesias of the lower limbs. These symptoms are usually unilateral. Lumbosacral plexopathy secondary to radiotherapy is usually painless. The duration of symptoms may vary from very acute (after a road traffic accident) to chronic (after radiotherapy). In extreme cases, muscle weakness and atrophy may be seen. Sphincter disturbances are rare & their presence should suspect cauda equine syndrome. Fever, chills, night sweats, fatigue, & weight loss may suggest malignancy or infection. A history of a road traffic accident, abdominopelvic neoplasm, radiotherapy, abdominal surgery, diabetes mellitus, bleeding disorders, or recent pregnancy hints towards LS plexopathy & narrows down the etiology.

- Physical examination may be normal in mild cases. Bruises may be seen in cases of trauma. A straight leg raise (SLR) test is positive in more than half of the patients. uneven lower limb muscle weakness may be seen with asymmetrically absent or decreased deep tendon reflexes. The knee jerk reflex is affected in lumbar plexopathy & ankle jerk is affected in sacral plexopathy. Muscle weakness in hip flexion, knee extension, or adduction indicates a possible injury to the lumbar plexus. Sensory loss may be present in a dermatomal pattern in cases of proximal Lumbosacral plexopathy involving the roots, or in the nerve distribution. Sensory changes to the medial thigh, anterior thigh, & medial leg can suggest lumbar plexus involvement; posterior thigh, dorsum of the foot, & perineum are likely related to sacral plexus involvement. Spinal point tenderness may be present, especially in cases of sacral fracture or infection. A rectal exam should be performed to assess rectal tone. Saddle anesthesia & bowel or bladder incontinence are rare & may be present, making it difficult to differentiate from cauda equina & conus medullaris syndromes. The inguinal region should also be palpated for suspected hematomas

Imaging

- MRI with gadolinium contradistinction is the best test for the evaluation of the Lumbosacral plexus. When there are contraindications to MRI (e.g., a noncompatible pacemaker), a computed tomography (CT) scan with contradistinction can be utilized. MR neurography is a useful modality compared to traditional MRI in Lumbosacral plexopathy judgment. Neurography assists identify extraspinal injuries responsible for neuropathic leg pain.

- In cases of malignancy, it can be demanding to differentiate direct compression from metastatic disease. Thus advanced imaging is often needed. MRI is frequently ordered for the starting evaluation of neoplasm-associated Lumbosacral plexopathy. Positron emission tomography (PET) is to find out the primary of malignancy. It also helps in the staging of the disease & subsequent treatment & prognosis.

Evaluation

- Neuroimaging, preferably, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the LS spine & electrodiagnostic studies (nerve conduction study & electromyography) are important in confirmation of the diagnosis of LS plexopathy.

Electrodiagnostic Studies

- Electrodiagnostic studies such as electromyography (EMG) are convenient to help differentiate lumbosacral plexopathy from other types of neuropathy or radiculopathies. Electromyography helps in the pinpointing of neurological injury. EMG can also help identify/differentiate malignancy from radiation-induced plexopathy. Myokymic discharges take place in cases of radiation-induced plexopathy but do not take place in cases of neoplasm. Myokymia is the spontaneous burst of an individual motor unit. These bursts occur several times per second & rhythmically. Denervation of the paraspinal muscles is commonly seen in radiculopathy & helps to differentiate from Lumbosacral plexopathy. Magnetic nerve root stimulation can aid in the detection of patients with contraindications to EMG (e.g. bleeding disorders). There are cases reported with the use of magnetic root stimulation for a more substantial analysis of nerve root damage under inspirational cases of lumbosacral plexopathy.

Laboratory Investigations

- Recommended blood tests to identify the etiology in patients with Lumbosacral plexopathy should include a complete blood count with an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), coagulation studies, autoantibodies testing (antinuclear antibodies (ANA), Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), Anti-Sjögren’s-syndrome-related antigen A, anti-Ro/anti-La antibodies, etc.) & hemoglobin A1c. Furthermore, serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP), angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) levels, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Lyme antibodies, rapid plasma reagin (RPR), & Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) serology may be indicated for specific cases.

Other Investigations

- If the cause of Lumbosacral plexopathy is still unknown against the above investigations, it indicates the need for a lumbar puncture. When malignancy is found, a biopsy of pelvic organs, as well as a biopsy of the assumed affected nerve root is needed. Sciatic nerve fascicular biopsies aid in the diagnosis of difficult cases; for cases of assumed malignancy present in the distribution of the sciatic nerve.

Treatment of Lumbosacral plexopathy

- Treatment for LS plexopathy depends upon the fundamental etiology. Symptomatic management with analgesics & muscle relaxants is given. Analgesics include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), pregabalin, gabapentin, duloxetine, amitriptyline, & opioids. Ankle-foot orthoses (AFOs) can be used for the foot drop. Appropriate antibiotics & antifungals are required for the infection.

- Diabetic amyotrophy is a temporary condition that usually sorts out with good glycemic control. Neuropathic pain treatments are advised for symptomatic management. In severe unremitting cases, steroids, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), cyclophosphamide, & even plasma exchange may be tried.

- In cases of malignancy, the primary tumor should be removed & accordingly managed. In severe symptomatic cases, a dorsal rhizotomy may be considered. Rhizotomy was shown to cause a significant decrease in pain & opioid usage in this population. This treatment method is primarily used for terminal patients.

- Radiation plexopathy can frequently present without pain, only weakness & sensory changes. Unlike other types of plexopathy, it is usually bilateral & can take place even years after radiation. There are no known treatments for radiation-produced plexopathy. Physiotherapy & rehabilitation are the mainstays of treatment. Further radiotherapy sessions should be discontinued.

- Surgical nerve repair techniques & nerve grafting have helped improve muscle function in pelvic fractures. One small study of 10 patients experiencing traumatic lumbosacral plexopathy, who go through nerve grafting showed significant improvement in muscle function at 38 months follow-up.

- Retroperitoneal hematoma is usually conservatively managed with blood transfusions & bed rest. Surgery is advised in cases of worsening hematoma or worsening neurological function.

Rehabilitation Program

- Physical Therapy

- For physical rehabilitation, the likely succession of neurologic weakness needs to be considered. If the patient is noted to have associated weakness after the acute pain has subsided, one may suggest active range-of-motion exercises, with forwarding to low-resistance exercises. Assistive devices, such as a cane, walker, & wheelchair, may be needed for ambulation in patients with weakness of the hip extensors, abductors,& quadriceps, with or without loss of joint position sense. Use of an ankle-foot orthosis &, in rare cases, a knee-ankle-foot orthosis may be beneficial for mobility.

- Occupational Therapy

- The occupational therapist should assess activities of daily living (ADL) & prescribe appropriate adaptive equipment. In particular, be aware that standing-transfer safety might be impaired in cases in which involvement is more distal than proximal.

Differential Diagnosis

- Cauda equina syndrome

- Conus medullaris syndrome

- transmitted sensory & motor neuropathy (also called Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease)

- Lumbosacral radiculopathy

- Mononeuropathies (e.g. Femoral polyneuropathy, sciatic polyneuropathy, common femoral polyneuropathy)

- Polyneuropathy (e.g. diabetic neuropathy, chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP), drug-related neuropathy)

- Spinal canal stenosis

- Spinal cord tumors

Prognosis

- The prognosis depends upon the underlying etiology, its response to treatment, & the timing of therapeutic intervention. The prognosis is good for patients with Lumbosacral plexopathy secondary to pregnancy, retroperitoneal hematoma, & diabetic amyotrophy. The majority of patients with pregnancy-related Lumbosacral plexopathy have a complete resolution of their symptoms two to six months following delivery.

- gradual neurological deterioration is common in patients with lumbosacral plexopathy secondary to malignancy. diagnosis is abysmal in neoplastic instances, with a mean survival of six months. Lymphoma has been demonstrated to be the most responsive tumor to therapy. At 42-month follow-up, 86% of patients diagnosed with LUBOSACRAL plexopathy secondary to malignancy had died.

- Traumatic Lumbosacral plexopathies are generally considered to have an unfavorable diagnosis but a case series of 72 patients with traumatic LS plexopathies demonstrated that more than two-thirds (about 70%) of patients recovered spontaneously within 18 months.

Complications

- Progressive neurological deterioration

- Intractable pain

- Bedsores

- Recurrent infections

- Joint contractures

Deterrence & Patient Education

The patient should be educated about the nature of the disease & its underlying etiology. As previously discussed, Lumbosacral plexopathy secondary to pregnancy, retroperitoneal hematoma, & diabetic amyotrophy are usually transient & improve with time. Patients with malignancy should be counseled & advised for further workup & management. Symptoms can progress over time, & worsen requiring the patient to have assistance with ambulation & activities of daily living.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Managing Lumbosacral plexopathy requires an interprofessional team of healthcare professionals that may include a primary care physician, physiotherapist, radiologist, pain medicine specialist, neurologist, obstetrician, neurosurgeon, or psychiatrist. Lumbosacral plexopathy can be a debilitating disorder & without proper management, the morbidity is high. After the initial diagnosis, treatment can be difficult & lifelong challenge. Symptoms can progress over time requiring the patient to have assistance with ambulation & activities of daily living. Consult with a mental health counselor if the patient has developed comorbid depression or anxiety in part because of their pain.

FAQ

What is the common cause of plexopathy?

There are numerous causes of brachial plexopathy, but some of the more common ones comprise compression of the plexus by cervical ribs or abnormal muscles (e.g., thoracic outlet syndrome), invasion of the plexus by tumor (e.g., Pancoast’s tumor syndrome), direct trauma to the plexus (e.g., stretch injuries & avulsions), …

Is lumbosacral plexopathy a spinal cord injury?

Excerpt. The lumbosacral (LS) plexus is a network of nerves formed by the anterior rami of the lumbar & sacral spinal cord. Lumbosacral plexopathy is an injury to the nerves in the lumbar &/or sacral plexus. Lumbosacral plexopathy is not a rare condition but can be difficult to diagnose & manage

What is the treatment for lumbosacral Plexopathy?

Treatment for Lumbosacral plexopathy depends upon the underlying etiology. Symptomatic treatment with analgesics & muscle relaxants is given. Analgesicscomprisee non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), pregabalin, gabapentin, duloxetine, amitriptyline, & opioids

What part of the body is affected by the lumbar plexus?

Lumbar plexus: Back, abdomen, groin, thighs, knees, calf. Sacral plexus: Pelvis bottom, genitals, thighs, calves, feet. Coccygeal plexus: A small region over the coccyx (the “tailbone”)

How is plexopathy treated?

Treatment

Medicines to control pain.

Physical therapy to help maintain muscle strength.

Braces, splints, & other devices to help the person to use the arm.

Nerve block, in which medicine is injected into the area near the nerves to decrease pain.

Surgery to repair the nerves or remove something pressing on the nerve

What happens when the lumbosacral plexus is damaged?

A traumatic lumbosacral plexopathy is an injury to the lumbosacral plexus that leads to pain in the low back &/or leg, weakness, paresthesia, &/or sphincter dysfunction. It is defined as an association from at least two different root levels from at least two different peripheral nerves.

What does plexopathy mean?

A complication affecting a network of nerves, blood vessels, or lymph vessels.

What is diabetic lumbosacral plexopathy?

Diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus polyneuropathy, also known as diabetic amyotrophy, has a characteristic course of sudden onset of unilateral pain in the thigh & hip, which might expand to the other side in weeks to months & proceeds with progressive lower extremity weakness, frequently resulting in the inability to walk.

One Comment