Patellar Tendinitis and Physiotherapy Treatment

- Patellar tendinitis is an injury to the tendon connecting the patella to the tibia. The patellar tendon works with the muscles at the front of the thigh to extend the knee so that can kick, run, and jump.

- Patellar tendinitis, also known as jumper’s knee, is most common in athletes whose sports involve frequent jumping — such as basketball and volleyball. However, even people who don’t participate in jumping sports can get patellar tendinitis.

- For most people, the treatment of patellar tendinitis begins with physical therapy to stretch and strengthen the muscles around the knee.

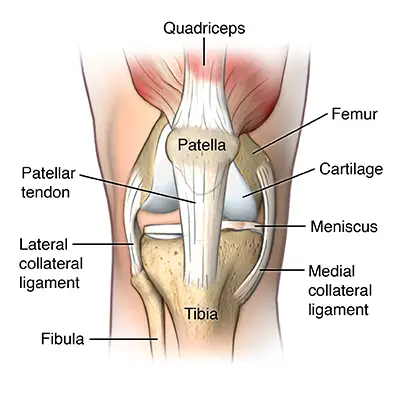

Anatomy related to Patellar tendinitis

- The quadriceps femoris is a four-headed muscle that inserts onto the tibial tuberosity. It extends the knee, and one head (rectus femoris) flexes the hip.

- The patella is a sesamoid bone that lies within the quadriceps tendon. The patellar tendon connects the apex of the patella to the tibial tuberosity and improves the way the quadriceps muscle pulls on the tibia.

- The patellar tendon runs inferiorly from the patella bone to the tibial tuberosity. The patella is a large sesamoid (a bone within a tendon) bone with a triangular transverse cross-section, that lies within the quadriceps tendon. Another example of a sesamoid bone is the pisiform carpal bone that lies within the tendon of the flexor carpi ulnaris.

- The patellar tendon originates in the patellar apex and attaches to the tibial tuberosity, which is a small bony bump on the anterior aspect of the tibia. The patellar tendon is technically not named correctly.

- A tendon is a connective tissue that connects a muscle to a bone, and the patellar ‘tendon’ in fact connects a bone to a bone (patella to tibial tuberosity). The correct name is therefore the patellar ligament. There are though some fibers of the tendon of the quadriceps femoris muscle, that blend with the patellar “tendon” and maybe this is the reason for this name issue. The patellar ligament is approximately 5 cm in length.

- However, its length is not constant and mostly increases from full extension to 30 degrees of knee flexion. The medial and lateral parts of the quadriceps femoris descend on either side of the patella and are inserted onto the upper anterior surface of the tibia.

- They merge into a continuous capsule and form the medial and lateral patellar retinacula. The posterior aspect of the patellar ligament is separated from the knee joint by an infrapatellar fat pad and a synovial membrane. An infrapatellar bursa also separates the patellar ligament from the tibia.

- The function of the patella is to increase the length of the lever arm of the patellar tendon and therefore allow the quadriceps femoris to exert a higher moment around the axis of rotation of the knee for a given level of muscle contraction than in the absence of a patella.

- The patella, whose peak thickness is between 2 and 3 cm, sits against the femur at a location that depends on the degree of knee flexion. This increase in lever arm ensures that knee extension is more efficient, and the action of the quadriceps femoris is clearly transmitted through to the tibia.

Causes of Patellar tendinitis

- Patellar tendinitis is a common overuse injury, caused by repeated stress on your patellar tendon. The stress results in tiny tears in the tendon, which your body attempts to repair.

- But as the tears in the tendon multiply, they cause pain from inflammation and weakening of the tendon. When this tendon damage persists for more than a few weeks, it’s called tendinopathy.

Risk Factors in Patellar tendinitis

A combination of factors may contribute to the development of patellar tendinitis, including:

- Physical activity: Running and jumping are most commonly associated with patellar tendinitis. Sudden increases in how hard or how often you engage in the activity also add stress to the tendon, as can changing your running shoes.

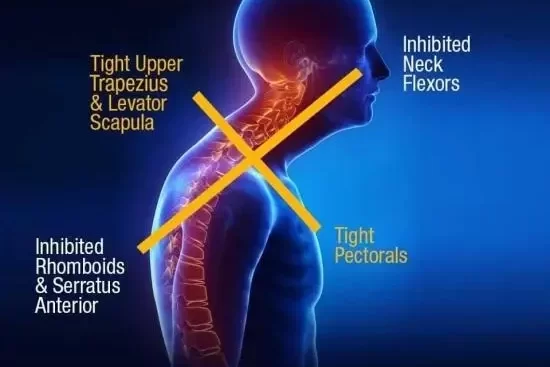

- Tight leg muscles: Tight thigh muscles (quadriceps) and hamstrings, which run up the back of your thighs, can increase strain on your patellar tendon.

- Muscular imbalance: If some muscles in your legs are much stronger than others, the stronger muscles could pull harder on your patellar tendon. This uneven pull could cause tendinitis.

- Chronic illness: Some illnesses disrupt blood flow to the knee, which weakens the tendon. Examples include kidney failure, autoimmune diseases such as lupus or rheumatoid arthritis, and metabolic diseases such as diabetes.

Clinical features of Patellar tendinitis

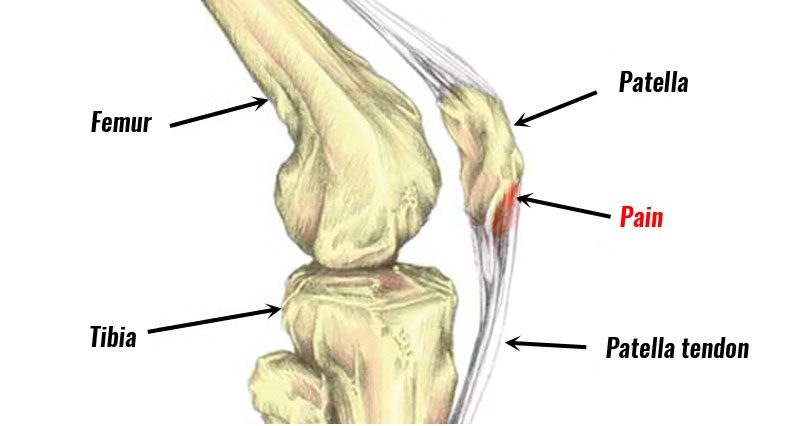

- Patellar tendinitis Open pop-up dialog box

- Pain is the first symptom of patellar tendinitis, usually between your kneecap and where the tendon attaches to your shinbone (tibia).

- Initially, you may only feel pain in your knee as you begin a physical activity or just after an intense workout. Over time, the pain worsens and starts to interfere with playing your sport.

- Eventually, the pain interferes with daily movements such as climbing stairs or rising from a chair.

Diagnosis of Patellar tendinitis :

- X-rays: X-rays help to exclude other bone problems that can cause knee pain.

- Ultrasound: This test uses sound waves to create an image of your knee, revealing tears in your patellar tendon.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): MRI uses a magnetic field and radio waves to create detailed images that can reveal subtle changes in the patellar tendon.

Examination in Patellar tendinitis

- Dose-dependent pain, see the previous section. Deficits in energy-storage activities can be assessed clinically by observing jumping and hopping. The stiff-knee vertical jump-landing strategy may be used by individuals with a past history of patellar tendinitis.

- Examination of the complete lower extremity is necessary to identify relevant deficits at the hip, knee, and ankle/foot regions. Atrophy, reduced strength, malaligned foot posture, quadriceps, and hamstring inflexibility, reduced ankle dorsiflexion have been associated with patellar tendinitis and should also be assessed.

- Patellar tendon imaging does not confirm patellar tendon pain, as pathology observed via ultrasound imaging may be present in asymptomatic individuals.

Medical management of Patellar tendinitis

- Pain relievers such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) or naproxen sodium (Aleve, others) may provide short-term relief from the pain associated with patellar tendinitis.

Physiotherapy management of Patellar tendinitis

- pain-relieving modalities such

- SWD: short wave diathermy is a deep heating modality that uses heat to provide pain relief, it improves the blood supply to targeted muscles, and removal of waste products.

- TENS: transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation is an electrical modality that provides pain relief by providing pain modulation.TENS closes the gate mechanism at the anterior grey horn in the spinal cord. also stimulates the endogenous opioid system which prevents the release of substance p at the anterior grey horn.

- IFT: Interferential current therapy produces a low-frequency effect at targeted tissue, it inhibits transmission of pain impulses, stimulates the endogenous opioid system, increases blood supply, relieves edema, and removes the waste products.

- Cold therapy: used to relieve inflammation and reduce pain, Ice Massage- Ice on the area of inflammation for anti-inflammatory effects. Use ice in a paper or Styrofoam cup (peeled away) for 5-7 minutes, make sure to avoid frostbite.

- Iontophoresis: This therapy involves spreading a corticosteroid medicine on your skin and then using a device that delivers a low electrical charge to push the medication through your skin.

ACUTE PHASE

- Rest: Rest prevents the worsening of the initial injury. By placing the injured extremity to rest the first 3-7 days after the trauma, we can prevent further retraction of the ruptured muscle stumps (the formation of a large gap within the muscle), reduce the size of the hematoma, and subsequently, the size of the connective tissue scar.

- During the first few days after the injury, a short period of immobilization accelerates the formation of granulation tissue at the site of injury, but it should be noted that the duration of reduced activity (immobilization) ought to be limited only until the scar reaches sufficient strength to bear the muscle-contraction induced pulling forces without re-rupture.

- At this point, gradual mobilization should be started followed by a progressively intensified exercise program to optimize the healing by restoring the strength of the injured muscle, preventing muscle atrophy, the loss of strength, and the extensibility, all of which can follow prolonged immobilization.

- Ice or cold application: It is thought to lower intra-muscular temperature and decrease blood flow to the injured area. Regarding the use of cold on injured skeletal muscle, it has been shown that early use of cryotherapy is associated with a significantly smaller hematoma between the ruptured myofiber stumps, less inflammation, and tissue necrosis, and somewhat accelerated early regeneration.

- However, according to the most recent data on the topic, icing of the injured skeletal muscle should continue for an extended period of time (6 hours) to obtain a substantial effect on limiting the hemorrhaging and tissue necrosis at the site of the injury.

- Compression: This may help decrease blood flow and accompanied by elevation will serve to decrease both blood flow and excess interstitial fluid accumulation. The goal is to prevent hematoma formation and interstitial edema, thus decreasing tissue ischemia.

- However, if the immobilization phase is prolonged, it will be detrimental to muscle regeneration. Cryotherapy, accompanied by compression, should be applied for 15–20 min at a time with 30–60 min between applications. During this time period, the quadriceps should be kept relatively immobile to allow for appropriate healing and prevent further injury.

- Elevation: The elevation of an injured extremity above the level of the heart results in a decrease in hydrostatic pressure, and subsequently, reduces the accumulation of interstitial fluid, so there is less swelling at the place of injury. But it needs to be stressed that there is not a single randomized, clinical trial to validate the effectiveness of the RICE principle in the treatment of soft tissue injury.

REHABILITATION PHASE

- Isometrics exercise of quadriceps will help to maintain muscle power of quadriceps muscle, Isometrics: Initial isometrics with quadriceps contractions done with the knee fully extended and in different positions at 20-degree increments as knee flexion improves May discontinue isometrics when the patient can sit comfortably.

- Straight leg raises: Sit flat on the floor with the legs straight out in front of you. Raise one leg off the floor keeping the knee straight. Hold for 3 to 5 seconds before lowering back to the ground. Repeat 10 to 20 times. This exercise can be done daily. Progress the exercise by increasing the length of hold and the number of reps.

- Isotonics: Once terminal knee extensions are done properly without extensor lag, free weights are added to the SLRs and terminal knee extensions. Begin with the lightest free weight that the patient can lift; three sets of 10 repetitions up to three times per day. Increase weight by no more than 2-3 pounds at any given time and increase no sooner than every two consecutive workdays.

- Wall squats: From your starting position, slowly lower your body down and hold for a time. As you improve, lengthen the amount of time you hold the wall squat. Be sure to keep your pelvis, back, and head against the wall. Keep the movement pain-free. (A variation to increase activation of the VMO would be to squeeze a ball between your knees as you perform the exercise. Typically the ball would be about 12 inches in diameter.)Perform 3 sets of 15-20 seconds holds once per day.

- Step-ups: Start with a box height that is comfortable for you to step upon. Be sure to keep your knee in alignment with your second toe. Step up and keep your pelvis level and your knee in alignment. Be sure to engage the buttocks muscles and fully lock out the knee. Return slowly back down to the ground. The focus should be on the slow eccentric (lowering) back to the ground for 1 second up and 3 seconds down. Perform 2 sets of 15-20 repetitions once per day.

2 Comments