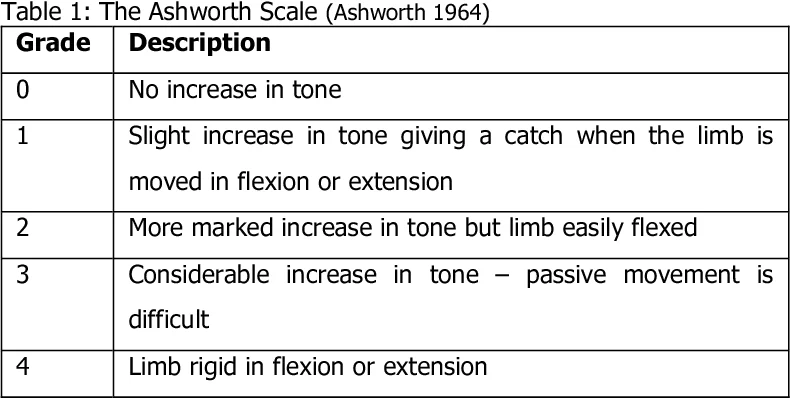

The Ashworth Scale

What is the Ashworth Scale?

The Ashworth Scale is a commonly used clinical assessment tool for evaluating muscle tone or spasticity in individuals with neurological conditions such as stroke, multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy, or spinal cord injuries. It is named after the British neurologist John Ashworth who developed the scale in 1964.

The Ashworth scale, also known as the Ashworth spasticity scale, is a diagnostic tool used to quantify the extent of spasticity or increased muscle tone in individuals. This condition results in stiffness and an imbalance between muscle contraction and relaxation. It is crucial that the scale is administered by experienced professionals with the assistance of the patient.

In our article, we will provide a comprehensive explanation of the Ashworth scale and its modified version. We will discuss the components that make up the scale, and its application procedure, and delve into its psychometric properties.

Additionally, we have an intriguing article on “Muscles of Respiration: Types, Characteristics, and Functions of Breathing.” We will rectify any writing mistakes and ensure that the content is unique.

The Ashworth scale, originally developed by Ashworth in 1964 and subsequently modified by Bahannon and Smith in 1989, is primarily employed to evaluate muscle tone and spasticity. Muscle tone guides the capability of muscles to keep a slight contraction.

This assessment tool comprises a subjective clinical scale enabling direct evaluation of muscle spasticity, ranging from no increase in muscle tone to extreme rigidity during muscle flexion or extension.

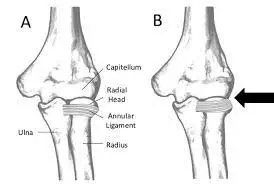

The Ashworth scale has been validated with patients affected by neurological conditions exhibiting varying degrees of spasticity. It has demonstrated excellent interobserver reliability for assessing spasticity in the elbow flexors and measuring plantar flexor spasticity.

The modified Ashworth scale incorporates additional components, including the angle at which resistance is encountered and the control of passive movement speed using a one-second count. This enhanced version is user-friendly and applicable to all joints, although it is particularly effective for assessing the upper extremities. However, there are still areas for improvement, such as the discrimination between degrees +1 and -1 or sensitivity.

History

The Ashworth Scale and Modified Ashworth Scale are both utilized to estimate spasticity. When administering these scales, the examiner passively moves the joint being assessed and rates the perceived resistance in the opposing muscle groups. Both scales consist of a single item and use a numerical rating system ranging from 0 to 4. A score of 0 indicates no increase in muscle tone, while a score of 4 indicates rigidity in flexion or extension of the affected part. It is important to note that the Ashworth scale is considered an ordinal scale, while the Modified Ashworth scale is considered a nominal scale due to the inclusion of the 1+ grade between 1 and 2, which introduces some ambiguity (Pandyan, Johnson, Price, Curless, Barnes, & Rodgers, 1999).

The Ashworth scale was initially described by Ashworth in 1964 (Ashworth, 1964), and later, in 1987, Bohannon modified it by introducing the 1+ grade to enhance sensitivity (Bohannon & Smith, 1987).

Items and application of the Ashworth scale

The Ashworth scale consists of five primary items, each assigned a numerical value ranging from 0 to 4. Additionally, there is an additional item included within scale 1.

Since the modified Ashworth scale is a subjective assessment tool, the scoring relies on the professional judgment of the healthcare provider administering it. It is crucial to note that this scale requires hetero-administration, meaning that neither the patient nor unqualified personnel is appropriate for conducting the assessment.

Psychometric properties

The psychometric properties of an instrument or rating scale encompass factors such as validity and reliability. These properties assess the effectiveness and consistency of the instrument in measuring what it claims to measure, as well as the stability of the measurement of each characteristic within the instrument.

Various psychometric studies have been conducted on the modified Ashworth scale to evaluate its efficacy and reliability in measuring and assessing spasticity and muscle hypertonia.

The key findings from these studies include:

- The Ashworth scale is considered reliable, useful, and valid as it accurately reflects the response to passive movements performed by healthcare professionals on specific joints.

- The modified scale includes a wider range of items compared to its predecessor since it assesses each joint and both sides of the body. There are even some contrasts in the evaluation method.

- As a diagnostic instrument, it provides an ideal assessment by requiring quantitative clinical measures of spasticity severity in each individual.

- It is an appropriate tool for assessing spasticity over time and monitoring patient improvement.

- The test’s reliability coefficient tends to approach its maximum value, indicating that the scale is relatively free from random errors. Scores from successive evaluations have shown stability.

- The modified Ashworth scale has demonstrated reliability in assessing spasticity in both upper and lower limbs.

- One limitation of the scale is its lower sensitivity when there is minimal variability in the degree of spasticity among subjects.

- Due to its subjective nature, the scale has limitations related to the individual evaluator’s expertise and personal profile.

Clinical Considerations

- The Ashworth Scale and Modified Ashworth Scale are commonly used in clinical settings to assess spasticity in individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI). However, it is important to note that spasticity is a complex construct with different components that are weakly interrelated, indicating that various clinical scales measure distinct aspects of spasticity.

- These scales primarily evaluate the resistance experienced during passive range of motion (ROM) or the velocity-dependent stretch reflex in single joints. They don’t especially handle spasm frequency/severity, nor do they differentiate between the phasic and tonic elements of spasticity. Therefore, to capture the overall construct of spasticity, it is best to utilize an appropriate battery of tests that may include the Ashworth or Modified Ashworth scales.

- One advantage of these scales is that they are well-tolerated by patients. They can be easily administered during routine clinic visits and do not require specialized equipment.

The scale is as follows:

| Ashworth Scale | |

|---|---|

| Grade | Description |

| 0 | No gain in muscle tone |

| 1 | Slight gain in muscle tone giving a catch when the extremity is driven |

| 2 | An additional considerable gain in muscle tone but the extremity effortlessly moved |

| 3 | A marked gain in muscle tone – passive motion hard |

| 4 | An additional considerable gain in muscle tone but the extremity smoothly moved |

| Modified Ashworth Scale | |

|---|---|

| Grade | Description |

| 0 | No increase in muscle tone |

| 1 | The affected part is rigid, with no ability for flexion or extension |

| 1+ | A small gain in muscle tone characterized by a catch obeyed by minimal resistance throughout less than half of the range of motion (ROM) |

| 2 | A more noticeable gain in muscle tone throughout most of the range of motion (ROM), but the involved extremity can be moved smoothly |

| 3 | A considerable gain in muscle tone makes passive movement difficult |

| 4 | The involved extremity is rigid with no capability for flexion/extension |

Some individuals believe that spasticity serves a purpose and that there is a rationale behind its existence. They argue that spasticity is a protective mechanism designed to safeguard the soft tissues, particularly muscles. According to this perspective, spasticity helps maintain the joints in a fixed position, thereby safeguarding the soft tissues.

However, if spasticity is indeed protective, it can be considered a rather crude mechanism. Spasticity typically involves the co-contraction of both agonist and antagonist muscles, rather than just the activation of one muscle group. For example, in the arm, spasticity often manifests as flexion of all joints, with the limb held close to the body. This combination of shoulder internal rotation, elbow flexion, and wrist and finger flexion indicates the dominance of flexor muscles over extensor muscles.

In other words, the elbow is flexed not solely due to the lack of spasticity in the triceps, but because the flexor muscles are significantly stronger than the extensor muscles. Similarly, in the lower extremity, spasticity often reflects the relative strength of plantar flexors, knee extensors, and hip internal rotators.

While therapies are typically the first approach in managing spasticity, therapists rarely measure spasticity directly. Instead, they assess spasticity by observing changes in movement, improvements in activities of daily living (ADLs), or by relying on their subjective assessment of resistance. However, the lack of a quantifiable measurement means that it is challenging to determine the effectiveness of interventions in addressing spasticity.

Difference Between The Ashworth Scale and Modified Ashworth Scale

The Ashworth Scale and the Modified Ashworth Scale (MAS) are both clinical assessment tools used to evaluate muscle tone or spasticity in individuals with neurological conditions. While they share similarities, there are important differences between the two scales. Here’s a comparison:

- Scoring System: The Ashworth Scale consists of six levels (0 to 4) to describe the resistance encountered during passive movement. The MAS, on the other hand, incorporates an additional category, “1+,” between levels 1 and 2. This allows for a finer grading of muscle tone and provides more nuance in the assessment.

- Increased Sensitivity: The addition of the “1+” category in the MAS increases its sensitivity compared to the Ashworth Scale. The MAS allows for a more detailed evaluation of muscle tone and can capture subtle changes in spasticity.

- Enhanced Granularity: The MAS offers a more refined assessment of muscle tone by differentiating between slight increases in muscle tone with and without a restriction of movement. This modification addresses a limitation of the Ashworth Scale, which lacked granularity in its scoring.

- Research Validation: The Ashworth Scale has been widely used for many years and has a substantial body of research supporting its reliability and validity. The MAS is an adaptation of the Ashworth Scale that aims to improve its shortcomings. Although the MAS has gained popularity, it may have varying levels of research validation compared to the original Ashworth Scale.

- Subjectivity: Both scales rely on the clinician’s subjective judgment and can be influenced by factors such as the evaluator’s experience, patient cooperation, and other contextual considerations. It is important for the evaluator to maintain consistent techniques and consider multiple clinical observations when using either scale.

Ultimately, the choice between using the Ashworth Scale or the Modified Ashworth Scale depends on the preferences of the healthcare professional, the specific needs of the assessment, and the available research supporting their use. Consulting with a healthcare professional experienced in spasticity assessments can help determine the most suitable scale for a particular situation.

For Good Measure

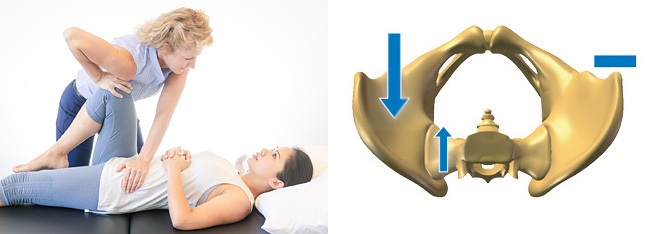

A convenient and straightforward method for measuring spasticity is by using the Ashworth Scale (AS). The AS assesses resistance encountered during the passive stretching of soft tissues. Here are the general guidelines for administering the Ashworth scale:

The Ashworth scale is typically conducted with the individual lying in a supine position, as this allows for the most accurate and lowest possible score. Tension in other areas of the body can increase spasticity.

Spasticity is known to be “velocity-dependent,” meaning that the faster a limb is moved, the greater the encountered spasticity. Therefore, the Ashworth scale involves moving the limb at a speed equivalent to the natural gravitational drop of a non-spastic limb. In other words, the movement should be relatively fast.

Each joint may only be tested a total of three times. Conducting the test more than three times can be influenced by the short-term effects of stretching, which can impact the resulting score.

It is recommended to administer the Ashworth scale before goniometric testing. Goniometric testing involves stretching the muscles, and the immediate impact of this stretch can affect the spasticity score.

Here are the commonly used positions for the Ashworth scale:

- Elbow: Starting position – Elbow completely bent, forearm neutral. Movement – Extend the elbow from maximum flexion to maximum extension. (For triceps, the position is the same but in the opposite direction.)

- Wrist: Starting position – Elbow as straight as possible, forearm pronated. Movement – Extend the patient’s wrist from maximum flexion to maximum extension.

- Fingers: Starting position – Elbow as straight as possible, forearm neutral. Movement – Extend all fingers simultaneously from maximum flexion to maximum extension.

- Thumb: Starting position – Elbow as straight as possible, forearm neutral, wrist in a neutral position. Movement – Extend the thumb from maximum flexion (against the index finger) to maximum extension (in anatomical position, “abducted”).

- Hamstrings: Starting position – Prone position with the ankle falling beyond the end of the plinth, hip in neutral rotation. Movement – Extend the patient’s knee from maximum flexion to maximum extension.

- Quadriceps: Starting position – Prone position with the ankle falling beyond the end of the plinth, hip in neutral rotation. Movement – Flex the patient’s knee from maximum extension to maximum flexion.

- Gastrocnemius: Starting position – Supine position with ankle plantarflexed, hip in neutral rotation and flexion. Movement – Dorsiflex the patient’s ankle from maximum plantarflexion to maximum dorsiflexion, not exceeding three consecutive repetitions, and rate the muscle tone.

- Soleus: Starting position – Supine position with ankle plantarflexed, hip in neutral rotation and flexion, and knee flexed to approximately 15°. Movement – Dorsiflex the patient’s ankle from maximum plantarflexion to maximum dorsiflexion.

The problem with the Ashworth scale relies on its endpoints. Technically, the Ashworth scale is a measurement for grading the resistance experienced while passive range of motion (PROM), instead of particularly testing spasticity. A score of “0” does not indicate “no tone” but a rather normal tone. Consequently, there is no score for tone below normal (flaccid). Furthermore, a score of “4” does not distinguish whether joint rigidity is due to a high degree of spasticity or contracture.

FAQ

What does the Ashworth Scale measure?

The Ashworth scale is a muscle tone examination scale utilized to evaluate the resistance encountered while the passive range of motion (PROM), doesn’t need any instrumentation and is fast to accomplish.

What is the normal Ashworth Scale?

Scoring: The Modified Ashworth Scale (MAS) is a 6-point scale. Scores grade from 0-4, where more low grades define regular muscle tone and more elevated grades describe spasticity. It’s indicated by excessive deep tendon reflexes(DTR) that interrupt muscular movement, gait, movement, or speech.

What are the scales for the assessment of spasticity?

The most well-prominent and generally utilized scale is the Ashworth scale (AS). Ashworth scale rates the muscle tone from 0 (normal) – 4 (severe spasticity). The use of this scale is comfortable however, the consequences rely on the examiner.

Does the Ashworth scale measure rigidity?

Original Ashworth Scale: Examinations resistance while passive movement around a joint with variable degrees of speed. Scores range from 0 to 4, with 5 options. A score of 1 means no resistance, and 5 suggests rigidity.

How do you test for spasticity and rigidity?

Spasticity is marked by abnormally elevated muscle tone, which oftentimes asymmetrically implicates muscle groups of antagonists. It’s both amplitude and velocity-dependent, therefore, nicely evaluated utilizing quick actions of the appropriate joint to induce short stretching of the muscle group affected.