Vertebrae Anatomy

Introduction

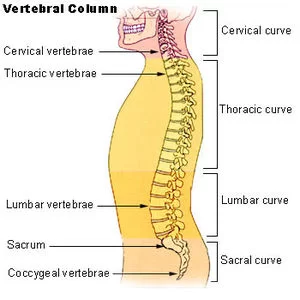

Vertebrae anatomy depends on the 33 separate bones that join together to create the spinal column are known as vertebrae. The areas of the vertebrae—cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacrum, and coccyx—are assigned numbers.

Structure and Function

- Protecting the spinal nerves and cord

The spinal cord is located in the spinal canal, a central lumen found in every vertebral body. At every vertebral level, spinal nerves branch off from the main cord to form the splanchnic and sympathetic trunk nerves.

The cervical and lumbar sections of the vertebral column have higher spinal canal diameters, whereas the thoracic area has lower spinal canal diameters.

Structural Support

In addition to supporting the head and transferring the weight of the trunk and abdomen to the spinal column, it also creates the central axis of weight bearing.

Provide Structure and Flexibility to the Body

- Movement: The spine’s special joint construction permits bending and rotation.

- The spine offers rib attachment sites in the thoracic area.

- Many muscles have attachment points on the spine.

- Cushioning in between vertebrae is provided by intervertebral discs.

- The cartilaginous structures between neighboring vertebrae that are made up of the annulus fibrosus and nucleus pulposus are called intervertebral discs.

- The discs make up around 25% of the vertebral column’s length.

- The anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments are supported by them.

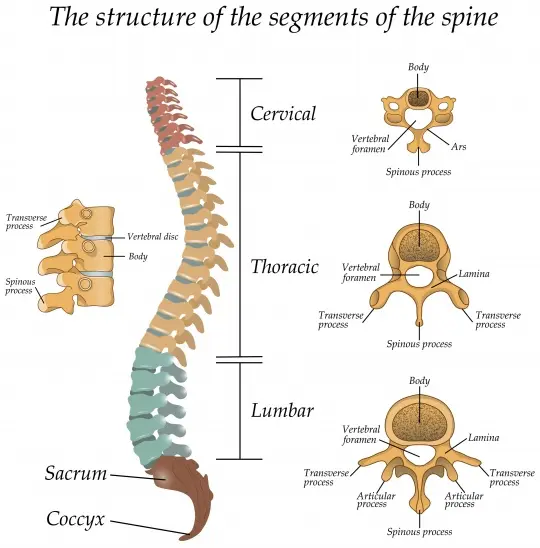

Structure of a Vertebrae

Every vertebrae has an identical fundamental structure. An anterior vertebral body and a posterior vertebral arch make up each of them.

Vertebral Body

Each vertebra’s anterior portion is called the vertebral body.

It is the component that bears weight, and the lower column’s vertebrae are greater in size than the top portion’s (to better sustain the additional weight).

Hyaline cartilage lines the superior and inferior surfaces of the vertebral body. A fibrocartilaginous intervertebral disc divides adjacent vertebral bodies.

Vertebral Arch

The vertebral arch forms the lateral and posterior portions of each vertebrae.

The vertebral arch creates the vertebral foramen, an enclosed hole, together with the vertebral body. The spinal cord is enclosed by the vertebral canal, which is made up of the alignment of all the vertebrae’s foramina.

Numerous bony prominences inside the vertebral arches serve as points of attachment for muscles and ligaments:

- Spinous processes: There is just one spinous process per vertebra, and it is positioned posteriorly near the arch’s tip.

- The transverse processes of the thoracic vertebrae articulate to form the ribs.

- The pedicles join the transverse processes to the vertebral body.

- Lamina: bridges the spinous and transverse processes.

- Joints between a vertebra and its superior and inferior counterparts are formed by articular processes. The junction of the laminae and pedicles is where the articular processes are situated.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The bigger arteries that serve the internal organs give rise to branches that supply the spinal arteries. The cervical ascending arteries and vertebral arteries of the spine are the offshoots of the subclavian arteries of the neck.

The lumbar arteries of the spine begin in the abdominal aorta, whereas the posterior intercostal arteries of the spine branch from the thoracic aorta. In the pelvis, the internal iliac arteries give rise to the lateral sacral arteries. There are anterior and posterior branches that divide each of these arteries that supply the spine.

Blood is supplied to the vertebral body by the anterior branch and the vertebral arch by the posterior branch. The vertebral column and the inside of the spinal canal are supplied by the radicular arteries that run along the center.

The internal and external vertebral veins, as well as the smaller veins of the spinal cord, are drained by radicular veins. Segmental and intervertebral veins get their emptying. Depending on where they are, blood travels from these veins into one of three big vessels.

The cervical spine’s drainage system is the superior vena cava. The lower lumbar and sacral spine areas are drained by the inferior vena cava, whereas the thoracic area is drained by the azygous and hemizygous veins.

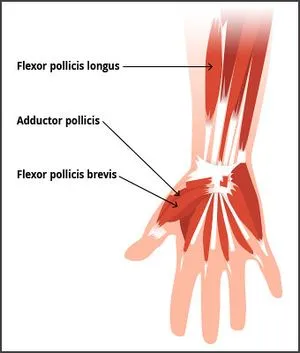

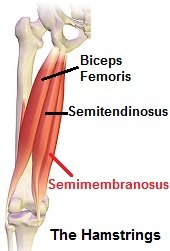

Muscles

The spine experiences extreme force as it is the main bone structure that supports weight. The muscles that connect to the spine assist in maintaining proper posture and distributing the body’s unequal weight distribution. Extrinsic and intrinsic back muscular groups are separated among them.

The extrinsic muscles are further subdivided into two groups: the superficial group, which includes the major and minor rhomboids, levator scapulae, latissimus dorsi, and trapezius, and the intermediate group, which includes the serratus posterior superior and inferior. The scapula and humerus are two examples of upper limb motions that are facilitated by the superficial extrinsic muscles. The movement of the ribs to facilitate breathing is controlled by the intermediate extrinsic muscles.

There are three levels to the intrinsic back muscles: superficial, middle, and deep. These muscles support and preserve posture during spinal movement. The superficial layer is made up of the splenius capitis and splenius cervicis. These have an impact on the flexion, rotation, and extension of the neck. The iliocostalis, longissimus, and spinalis are the paraspinal or erector spinal muscles, which comprise the majority of the intermediate layer. The erector spinae play a crucial role in preserving and lengthening the spine’s center curvature, as their name suggests.

The muscles located between the transverse and spinous processes of the vertebrae are part of the deep layer of the intrinsic back muscles. These three muscle groups are together referred to as the paravertebral muscles at times. The most superficial is the semispinalis, which is noticeable in the cervical and thoracic areas. The multifidus is particularly noticeable in the lumbar area and extends deep to the semispinalis. Lastly, the thoracic area is home to the deepest and most noticeable rotator cuff muscles.

Deep in the nape of the neck lie the suboccipital muscles. They are attached to the skull and have a role in head movement. These comprise the rectus capitis posterior major, obliquus capitis superior, and obliquus capitis inferior, the muscles that compose up the suboccipital triangle. The vertebral artery loops through this triangle, from the transverse foramen of the atlas into the foramen magnum of the skull, where it nourishes the brainstem. This makes the triangle significant.

Vertebrae

The bony structure that extends from the inferior side of the occipital bone of the skull to the tip of the coccyx is known as the spine, vertebral column, or backbone. On the other hand, the tubular nerve tissue that passes through the vertebral canal of the spinal column is called the spinal cord.

- Nerves in the spinal column and vertebrae

- We have how many vertebrae?

- There are 33 vertebrae in the vertebral column overall, which are arranged as follows:

- Cervical vertebrae (7)

- Thoracic vertebrae (12)

- Lumbar vertebrae (5)

- Sacrum (5 fused)

- Coccyx (3-4 fused)

- Mnemonic: ‘Can This Little Servant Cook?’ is a very easy mnemonic to help you recall the five areas of the spinal column.

Typical vertebra

Vertebrae are not all alike. Their scope and traits differ, particularly between different regions. But they all have the same fundamental structure:

- The big, cylindrical portion of the vertebral body, which is situated anteriorly and provides the spine with strength. They bear weight in some capacity.

- As one moves down the spinal column, it gets bigger. Intervertebral discs divide adjacent vertebral bodies apart.

- The anatomical structure posterior to the body is called the vertebral arch. It is made up of two laminae and two pedicles. Intervertebral foramina are formed by the superior and inferior vertebral notches seen on the pedicles. These help the spinal nerves leave the spinal cord more easily. Each vertebra has a hollow that is formed by its body, laminae, and pedicles (vertebral foramen). The area of the spinal column that the vertebral foramina surrounds is known as the vertebral canal.

- Vertebral processes: two transverse (posteriolateral) processes, four articular processes, and one spinous process (posterior inferior) are among the seven that protrude from the vertebral arch. The latter has aspects that are articulated. Ligaments and muscles of the back attach to the vertebral processes. They participate in joint formation as well.

Features of a typical vertebra

Cervical vertebrae

The cervical spine of the neck is made up of the seven cervical vertebrae. They have the tiniest and thinnest intervertebral discs and are situated between the head and the thoracic vertebrae. They do, however, have the greatest range of motion in the whole spinal column. Furthermore, transverse foramina, two tubercles (anterior and posterior), and split (bifid) spinous processes are characteristics unique to cervical vertebrae. This figure shows the anatomy of the cervical spine.

- Atlas superior view (C1) and axis posterior view (C2)

- 1/3

- There are three abnormal cervical vertebrae. The atlas (C1) has two lateral masses and two arches, anterior and posterior.

The masses sustain the weight of the skull by articulating with its occipital condyles. The axis (C2) has two superior articular surfaces and an upward protrusion that resembles a tooth (dens or odontoid process). They make head rotation and articulation with the atlas easier. The longest spinous process belongs to Vertebra prominens (C7). It’s the bony protrusion at the back of your neck that protrudes the greatest. C3–C6), the remaining cervical vertebrae, are normal.

Vertebral body

Thoracic vertebrae

The thoracic spine, or upper back, is the second part of the vertebral column and is made up of the twelve thoracic vertebrae. They contribute to the formation of the thoracic cage. Numerous characteristics set thoracic vertebrae apart, including smaller vertebral foramina, heart-shaped vertebral bodies, long, strong spinous and transverse processes that point inferiorly, and costal facets that engage with the ribs. There are certain similarities between the cervical and lumbar spines and the first four (T1-T4) and last four (T9-T12) thoracic vertebrae, respectively. The usual thoracic vertebrae are the middle four (T5-T8). Discs in the vertebral bodies are thicker than those in the cervical spine.

Lumbar vertebrae

Synonyms: Vertebrae L1-L5

The lumbar spine, or lower back, is made up of the five lumbar vertebrae. They can withstand more weight because they have the biggest vertebral bodies in the entire spinal column. The laminae and pedicles are robust and substantial. Strong lumbar muscles can connect to their short, robust spinous processes. In contrast to other varieties of vertebrae, the articular processes are positioned differently. The mammillary and accessory processes are also located in the lumbar spine. As the biggest vertebra in the human body, L5 bears the weight of the body and transfers it to the base of the sacrum. At the level of the L1/L2 vertebra, the spinal cord ends as the conus medullaris, also known as the medullary cone.

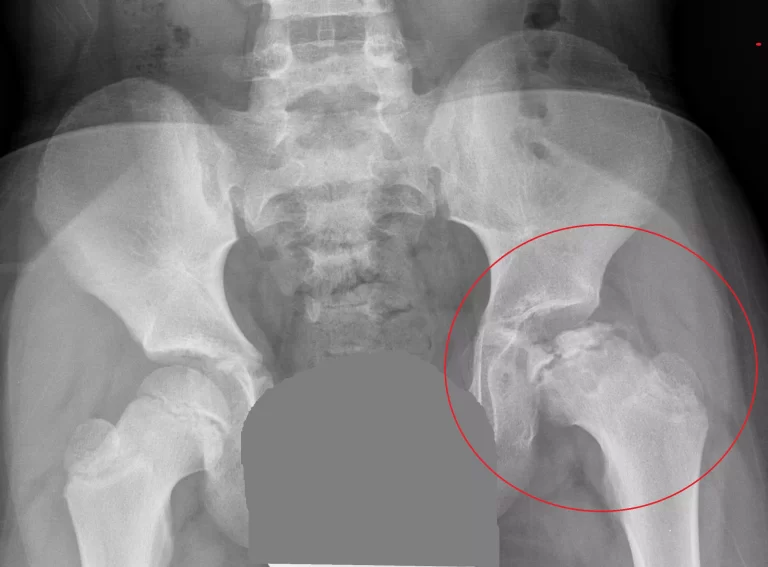

Pelvis

The lumbar spine’s bones, articulations, and unique characteristics (18 structures).

Because of the usual structure of the vertebrae, learning the anatomy of the lumbar spine is not too difficult. Find out more about them in the sections below:

Sacrum

The five united sacral vertebrae make up the sacrum. It is a portion of the pelvis and is situated between the coccyx and the lumbar spine (lumbosacral angle). Its primary function is to transfer all of the upper body’s weight to the pelvis so that the lower limbs may be reached.

The sacrum is composed of three surfaces (pelvic, posterior, and lateral), an apex, and a base. The sacral canal, which is the spinal canal’s continuation, is located at its center. The spinal cord’s cauda equina is located in the sacral canal. The spinal nerves can leave via the anterior and posterior sacral foramina. The fused processes of the sacral vertebrae are represented by the sacral crests (median, intermediate, and lateral).

Coccyx

Recall your most recent instance of falling on your gluteus maximus. The pain is so intense that it’s one of the rare occasions when you become conscious of your tailbone. The coccyx, or tailbone, is made up of three or four fused coccygeal vertebrae and articulates with the sacrum. It has coccygeal cornua, short transverse projections, and two surfaces (pelvic and posterior). The coccyx serves as the attachment site for the coccygeal and gluteus maximus muscles. At the level of the first coccygeal vertebra (Co1), the spinal cord’s filum terminal ends.

Intervertebral discs

An intervertebral disc cushions and separates each vertebra in your spine, preventing the bones from rubbing against one another.

Discs are made similarly to radial tires for cars. Similar to a tire tread, the annulus, the outer ring, is made up of crisscrossing fibrous bands. These bands fasten in the spaces between each vertebra’s bodies. Similar to a tire tube, the disc has a gel-filled core known as the nucleus.

Facet joints

Back mobility is made possible by the spine’s facet joints. Every vertebra contains four facet joints: inferior facets link to the vertebra below, while superior facets connect to the vertebra above.

Every vertebra is connected by its superior and inferior facets.

Every vertebra is joined by its superior and inferior facets.

There are four facet joints associated with each vertebra.

Ligaments

Strong fibrous bands called ligaments stabilize the spine, keep the vertebrae together, and shield the discs. The ligamentum flavum, anterior longitudinal ligament (ALL), and posterior longitudinal ligament (PLL) are the three main ligaments of the spine. Along the vertebral bodies, the ALL and PLL are continuous bands that extend from the top to the bottom of the spinal column. They stop the spinal bones from moving too much. The ligamentum flavum is attached in the space between each vertebra’s lamina.

Spinal cord

The spinal cord is the thickness of your thumb and measures around eighteen inches in length. It travels down the spinal canal, shielded, from the brainstem to the first lumbar vertebra. The spinal cord’s fibers split into the cauda equina at its terminus, descend the spinal canal to your tailbone, and then split off to form your legs and feet.

The spinal cord transmits information from the brain to the body, acting as a superhighway for information. Through the spinal cord, the brain transmits motor signals to the limbs and body, enabling movement. Via the spinal cord, the body’s limbs communicate what we sense and touch to the brain. Occasionally, the spinal cord might respond without informing the brain. The purpose of these unique circuits, known as spinal reflexes, is to instantly defend our body from injury.

Any spinal cord injury has the potential to cause loss of motor and sensory function below the site of the lesion. For instance, a thoracic or lumbar injury may result in paraplegia or the loss of motor and sensory function in the legs and trunk. Tetraplegia, formerly known as quadriplegia, is the term used to describe the sensory and motor loss of the arms and legs following damage to the cervical (neck) region.

Spinal nerves

The spinal cord splits into thirty-one pairs of spinal nerves. In order to govern sensation and movement, the spinal nerves function as “telephone lines,” sending and receiving signals between your body and the spinal cord.

Spinal nerves have two roots each. Motor impulses leave the brain through the ventral (front) root, whereas sensory impulses enter the brain through the dorsal (back) root. Together, the dorsal and ventral roots give rise to a spinal nerve, which passes alongside the cord as it descends the spinal canal to the intervertebral foramen, which is where it exits the body. The nerve divides into branches once it crosses the intervertebral foramen; these branches include both motor and sensory fibers.

The skin and muscles of the rear of the body are supplied by the smaller branch, which is known as the posterior main ramus, which rotates posteriorly. The majority of the main nerves are formed by the bigger branch, known as the anterior primary ramus, which curves anteriorly to feed the front of the body’s muscles and skin.

The vertebrae above which a spinal nerve emerges from the spinal canal determines the nerve’s number. There are twelve spinal nerves: T1 through T12 in the thoracic region, L1 through L5 in the lumbar region, S1 through S5 in the sacral region, and C1 through C8 in the cervical region. The coccygeal nerve is singular.

The vertebral column contains the spinal cord. It stops at the conus medullaris and filum terminale after extending from the base of the brain to the base of the spine. The tapering, cone-shaped end of the spinal cord is called the conus medullaris. In adulthood, it normally ends around L1–L2, however, anatomical variants may let it extend beyond. The conus medullaris is as low as L3–L4 in infants. For operations like the lumbar puncture, when the goal is to lower the risk of spinal cord injuries, the finishing site is important. From the conus medullaris, the spinal cord extends delicately to the filum terminale, which attaches to the dorsum of the coccyx. The conus medullaris gives rise to the cauda equina, or “horse’s tail.”

Thirty-one pairs of spinal nerves innervate the periphery after emerging from the spinal cord through the intervertebral foramen.

The spinal nerves’ meningeal branches regulate the vertebrae.

The body’s dermatomes, or striped patterns, are formed by the spinal nerves’ innervation of certain regions. Based on the area of discomfort or weakness in the muscles, doctors can use this pattern to determine where a spinal issue is located. For instance, sciatica, or leg pain, typically signals a problem in the vicinity of the L4-S3 nerves.

Coverings & spaces

The same three meningeal membranes that cover the brain also cover the spinal cord. The pia mater, the inner membrane, is closely linked to the cord. The arachnoid mater is the following membrane. The robust dura mater is the outer membrane. Spaces are utilized in diagnostic and therapeutic operations between these membranes.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is found in the broad subarachnoid space, which lies between the arachnoid mater and pia and envelops the spinal cord. The most common ways to reach this area are during a myelogram to inject contrast dye or during a lumbar puncture to sample and evaluate CSF. The epidural space is the area that exists between the dura mater and the bone. The most common uses of this area are for injecting steroid medicine and administering anesthetic numbing chemicals, sometimes known as epidurals (see Epidural Steroid Injections).

Overview

The 33 separate bones that join together to create the spinal column are known as vertebrae. The areas of the vertebrae—cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacrum, and coccyx—are assigned numbers. The vertebrae of the sacrum and coccyx are united so that only the top 24 bones are mobile. Each region’s vertebrae has distinct characteristics that enable them to carry out their primary duties.

FAQs

What is the anatomy of a vertebra?

Vertebrae. The 33 separate bones that join together to create the spinal column are known as vertebrae. The areas of the vertebrae—cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacrum, and coccyx—are assigned numbers.

What is the anatomy of the vertebrae and disc?

Understanding Intervertebral Discs in Spinal Anatomy

An intervertebral disc is a cushion that lies between each vertebral body. Each disc keeps the vertebrae from grinding against one another by absorbing the shock and strain the body experiences during movement. The biggest structures in the body without a blood supply are the intervertebral discs.

What are the vertebrae in anatomical position?

The typical spine is a straight line with one vertebra right on top of the other when seen from the front or back. Scoliosis is the term for an alternating curvature of the spine. The typical spine has three progressive bends when seen from the side: The lordosis of the neck causes it to bend backward.

What is the structure and function of the vertebrae?

Vertebrae: The 33 stacked vertebrae (small bones) in your spine make up the spinal canal. Your spinal cord and nerves are housed in the spinal canal, a tunnel designed to keep them safe from harm. The majority of vertebrae flex to provide a range of motion. The sacrum and coccyx, the lowest vertebrae, are fused together and immobile.

What is a vertebrae?

About the spine’s vertebrae. About 24 bones, or vertebrae, make up the adult spine, which extends from the base of the cranium to the pelvis.

References

- The joints, vertebrae, and vertebral structure of the vertebral column. TeachMeAnatomy. https://teachmeanatomy.info/back/bones/vertebral-column/

- Anatomy, Back, Vertebral Column. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525969/

- Vertebral column (spine). Kenhub. https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/the-vertebral-column-spine

One Comment