Cubital Tunnel Syndrome

Definition/Description

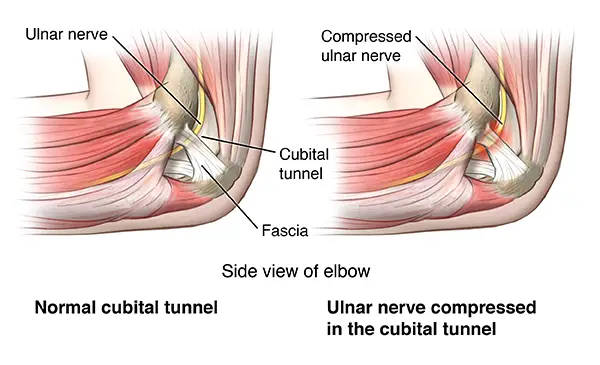

Cubital tunnel syndrome (CBTS) is a peripheral nerve compression syndrome. It is an irritation or injury of the ulnar nerve in the cubital tunnel at the elbow. This is also termed ulnar nerve entrapment and is the second most common compression neuropathy in the upper extremity after carpal tunnel syndrome.

It represents a source of considerable discomfort and disability for the patient and may, in extreme, cases lead to a loss of function of the hand. Cubital tunnel syndrome is also often misdiagnosed.

Peripheral nerve compression syndromes are characterized by chronic irritation and pressure lesions on the sites where nerves have to pass through narrow anatomic spaces and fibro-osseous structures. The main clinical manifestations of this type of compression are paresthesia, sensory impairment, and paresis.

Cubital tunnel syndrome can also be caused by traction, pressure, or ischemia of the ulnar nerve which passes through the cubital tunnel at the medial side of the elbow. Pain or paraesthesia in the fourth and fifth fingers and pain in the medial aspect of the elbow, which may extend proximally or distally, is caused by compression of the ulnar nerve. There is only limited evidence that proves the effectiveness of nonsurgical and surgical interventions to treat cubital tunnel syndrome.

Cubital tunnel syndrome is a problem with the ulnar nerve, which passes through the inside of the elbow. It causes pain that feels a lot like the pain you feel when you hit the “funny bone” in your elbow.

What is cubital tunnel syndrome?

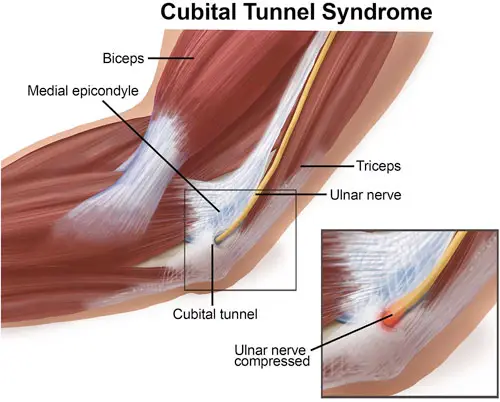

Cubital tunnel syndrome happens when the ulnar nerve, which passes through the cubital tunnel (a tunnel of muscle, ligament, and bone) on the inside of the elbow, is injured and becomes inflamed, swollen, and irritated.

Cubital tunnel syndrome causes pain that feels a lot like the pain you feel when you hit the “funny bone” in your elbow.

The “funny bone” in the elbow is actually the ulnar nerve, a nerve that crosses the elbow. The ulnar nerve starts in the side of your neck and ends in your fingers.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

Cubital tunnel syndrome is a progressive entrapment neuropathy of the ulnar nerve at the medial aspect of the elbow.

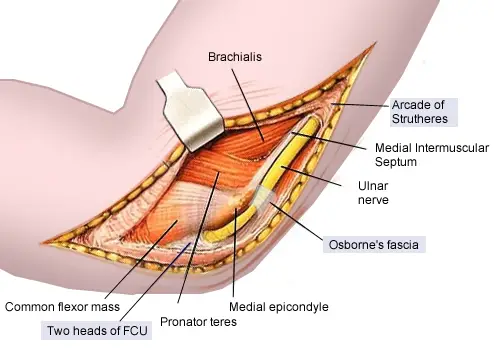

The ulnar nerve, which is a motor and sensory nerve, is formed from the medial cord of the brachial plexus and originates from nerve roots C8 and T1. The ulnar nerve travels down the posterior aspect of the arm to eventually traverse posterior to the medial epicondyle through an area known as the cubital tunnel. The cubital tunnel extends from the medial epicondyle of the humerus to the olecranon process of the ulna.

The nerve runs superficial to the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) and deep to the aponeurotic attachment of the flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU), which is also known as Osborne’s ligament. Once the ulnar nerve reaches the proximal border of Osborne’s ligament it is located in the cubital tunnel.

The roof of the cubital tunnel is formed by the cubital tunnel retinaculum which is about 4 mm between the medial epicondyle and the olecranon. The floor of the tunnel consists of the elbow joint capsule and the posterior band of the medial collateral ligament of the elbow. It contains several structures of which the most important is the ulnar nerve.

After passing through the cubital tunnel, the ulnar nerve passes deep into the forearm between the ulnar and humeral heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris.

Ulnar nerve entrapment can occur at 5 possible sites around the elbow:

- Arcade of Struthers (approximately 10cm proximal to the medial epicondyle)

- Medial intermuscular septum (runs from the arcade to the epicondyle)

- Medial epicondyle

- Cubital tunnel (retinaculum)

- Deep flexor pronator aponeurosis (about 5cm distal to the epicondyle)

- Out of all the sites, the cubital tunnel is the most common site for entrapment

Compressive neuropathy of the ulnar nerve

2nd most common compression neuropathy of the upper extremity

- Sites of entrapment

- most common

- between the two heads of FCU/aponeurosis (most common site)

- within the arcade of Struthers (hiatus in the medial intermuscular septum)

- between Osborne’s ligament and MCL

- less common sites of compression include

- medial head of triceps

- medial intermuscular septum

- medial epicondyle

- fascial bands within FCU

- anconeus epitrochlearis (anomalous muscle from the medial olecranon to the medial epicondyle)

- aponeurosis of FDS proximal edge

- external sources of compression

- fractures and medial epicondyle nonunions

- osteophytes

- heterotopic ossification

- tumors and ganglion cysts

- Associated conditions

- cubitus varus or valgus deformities

- medial epicondylitis

- burns

- elbow contracture release

Causes of Cubital Tunnel Syndrome:

- Cubital tunnel syndrome may happen when a person bends the elbows often (when pulling, reaching, or lifting), leans on their elbow a lot, or has an injury to the area.

- Arthritis, bone spurs, and previous fractures or dislocations of the elbow can also cause cubital tunnel syndrome.

- In many cases, the cause is not known.

Symptoms of Cubital tunnel syndrome:

The following are the most common symptoms of cubital tunnel syndrome:

- Numbness and tingling in the hand or ring and little finger, especially when the elbow is bent

- Numbness and tingling at night

- Hand pain

- Weak grip and clumsiness due to muscle weakness in the affected arm and hand

- Aching pain on the inside of the elbow

- The symptoms of cubital tunnel syndrome may seem like other health conditions or problems, including golfer’s elbow (medial epicondylitis). Always see a healthcare provider for a diagnosis.

- The ulnar nerve is also sometimes called the funny bone nerve. Where the ulnar nerve crosses the elbow, there is very little fat and subcutaneous tissue, meaning the nerve is closer to the surface of the skin and more sensitive. Hence, if a person hits their inner elbow, the sensation can resemble an electric shock.

- Most people with cubital tunnel syndrome experience symptoms that may include:

- numbness, pain, and weakness in the arm, forearm, and fingers

- weakened or reduced grip

- waking at night from pain or numbness in the hands or fingers, especially the pinky and ring fingers

- difficulty bending and straightening the fingers

- difficulty manipulating things with the hands or fingers

- muscle loss at the base of the small fingers

- The symptoms of cubital tunnel syndrome usually get much worse when the elbow is bent for a long time or compressed.

Clinical presentation

- Patients suffering from cubital tunnel syndrome are 4 times more likely to present with atrophy than patients suffering from carpal tunnel syndrome.

- The patient may also report non-painful snapping or popping during active and passive flexion and extension of the elbow.

- Wartenberg sign (abduction of the fifth digit due to weakness of the third palmar interosseous muscle) may be present.

- Active and passive ROM may not be decreased.

- The ulnar nerve may be enlarged or palpable and tender in the groove.

- On observation, there may be atrophy of the intrinsic muscles of the hand, which is often not noticed by the patient, with abnormal claw posture of the 4th and 5th fingers.

Diagnosis

In addition to a complete medical history and physical exam, diagnostic tests for cubital tunnel syndrome may include:

- Nerve conduction test. A test to find out how fast signals travel down a nerve to find a compression or constriction of the nerve.

- Electromyogram (EMG). This test checks nerve and muscle function and may be used to test the forearm muscles controlled by the ulnar nerve. If the muscles don’t work the way they should, it may be a sign that there is a problem with the ulnar nerve.

- X-ray. This is done to look at the bones of the elbow and see if you have arthritis or bone spurs in your elbow.

Examination

Accurate diagnosis includes assessing the following:

- sensory changes in the ulnar nerve distribution (½ of the 4th digit and entirety of the 5th)

- pain

- atrophy of the intrinsic muscles of the hand innervated by the ulnar nerve

- neural provocation test of the ulnar nerve

- sparing of the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle

- Tests used to confirm the diagnosis of cubital tunnel syndrome are those linking ulnar neuropathy and the elbow. These tests should evoke provocative signs as a reaction to confirm the syndrome, such as elbow flexion reproducing symptoms, positive Tinel’s sign tested at the elbow, or a sign of instability, for example snapping of the ulnar nerve over the medial epicondyle with elbow flexion.

Elbow Flexion Test

Typically performed bilaterally with the shoulder in full external rotation and the elbow actively held in maximal flexion with wrist extension held for one minute. Symptoms are produced as maximal elbow flexion reduces the cubital tunnel volume by approximately 55% causing increased neural pressure on the ulnar nerve. This test can include additional components such as wrist extension and wrist flexion or sustained maximal elbow flexion for up to 3 minutes. A positive test is the reproduction of pain at the medial aspect of the elbow and numbness and tingling in the ulnar distribution on the involved side. This test has a high positive predictive value (0.97), indicating a high probability of cubital tunnel syndrome if positive, with high specificity (0.99) and sensitivity (0.75).

Pressure Provocative Test

Pressure is applied to the ulnar nerve at the cubital tunnel with the UE positioned as in the elbow flexion test for 30 seconds. Sensitivity with this test is high (0.91)

Tinel Sign

Reproduction of tingling and numbness into the 4th and 5th digits by tapping of the ulnar nerve at the cubital tunnel. Test specificity is 0.98 and sensitivity is 0.70. The clinician will proceed with percussions on the ulnar nerve as it passes through the cubital tunnel after the ulnar groove, posterior of the medial epicondyle of the humerus. There is no agreed consensus on the number of percussions, but 4 to 6 taps should be sufficient to reproduce symptoms. A positive test is the reproduction of tingling and numbness in the ulnar nerve distribution on the involved side. Caution must be taken, however, when interpreting the results as a positive test has been found in 24% of asymptomatic subjects and it could also be negative for those in the advanced stage of the diagnosis due to the nerve no longer regenerating.

Scratch Collapse Test

The patient’s skin is lightly scratched over the area of nerve compression whilst resisted bilateral shoulder external rotation is performed. A brief loss of muscle resistance will be elicited if the patient has allodynia due to compression neuropathy. Sensitivity for the scratch collapse is 69% compared with 54% and 46% for the Tinel test and elbow flexion compression test, respectively. Of all tests for the cubital tunnel, the Tinel test has the highest negative predictive value (98%). Research suggests the Scratch collapse test has a significantly higher sensitivity than Tinel’s test and the flexion/nerve compression test for carpal tunnel and cubital tunnel syndromes. This novel test provides a useful addition to existing clinical maneuvers in the diagnosis of these common nerve compression syndromes.

Operative Management

Indications for surgical intervention include moderate muscle weakness without response to conservative treatment after 3 months and an electrodiagnostic test of less than 39-50 meters per second across the elbow. Surgery may also be indicated in cases of:

- progressive symptoms

- sensorimotor deficits

- lack of clinical and electro-neurographic improvement

- worsening of the objective findings on follow-up several weeks after the initial visit.

Simple decompression

A release of Osborne’s ligament through an incision traversing in a proximal to distal direction throughout the length of the ligament increasing the space in the cubital tunnel. A 6 to 10-cm incision is made along the course of the ulnar nerve between the medial epicondyle and the olecranon. Care should be taken to avoid the branches of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve. Osbourne’s ligament is released as are the FCU superficial and deep fascia.

It has been shown to be successful in treating cubital tunnel syndrome. Data suggests that in situ decompression is a reliable treatment with a low failure rate and anterior trans-positioning can be used to treat those patients with recurrent symptoms. Decompression is the most commonly performed surgical treatment. It can be done in conjunction with a medial epicondylectomy

Physical Therapy Management in Cubital Tunnel Syndrome

Conservative treatment has been shown to have a 90% success rate in acute ulnar irritation with symptoms often resolving within 2-3 months. A non-surgical approach should be followed for at least a 3-month period before considering surgical intervention, especially with mild cases.

Conservative treatment may include a 4-6 week period of immobilization with the elbow splinted at 45 degrees of flexion and the forearm in neutral rotation, activity modification, electrotherapy modalities, anti-inflammatories, soft elbow pads, joint mobilizations, neural flossing, neural gliding, exercise, and patient education.

Active rest is recommended for athletes. Return to throwing is allowed at 4-6 weeks following the absence of symptoms with daily activities or exercise and return to full ROM and strength. While there is strong evidence in support of splinting, activity modification, and patient education, only low-level evidence supports manual techniques such as nerve glides, joint mobilization manipulation, and exercise. Despite the low-level evidence, improvements have still been seen with manual techniques in patients with cubital tunnel syndrome.

The initial goal of conservative treatment for cubital tunnel syndrome is to control and decrease paraesthesia and pain. When symptoms are mild and aggravating activities can be identified, the first step is to eliminate those pain-provoking activities. When symptoms occur in a wider range of activities such as work, therapy becomes more complex and can consist of activity modifications, splinting, and rest. With this combination, pain, and paraesthesia become more controllable.

Therapy begins with education about the development of symptoms and how certain activities can influence those symptoms. such as stretching or compressing the nerve when collaterally tilting the head or abducting, depressing or externally rotating the shoulder, supinating the forearm, or extending the wrist. The patient is educated about pain-provoking movements and how best to avoid them in ADLs, which could cause aggravation of the symptoms. For many patients, this could mean lifelong management.

the effect of rigid night splinting for a period of three months combined with activity modification appears to be successful. Prolonged elbow flexion (static or repetitive) puts strain on the ulnar nerve and increases extraneural and intraneural pressure in the cubital tunnel. The lowest value of these pressures is at an elbow position of 40-50 degrees of flexion. Pressures are significantly higher in full flexion or extension of the elbow. Splinting is designed to alleviate symptoms and prevent the progressive dysfunction of nerves. Two issues that should be considered, however, are the ability of the splint to maintain the elbow at the ideal amount of flexion and patient compliance with night splinting.

As well as education, immobilizing the elbow with splints can reduce swelling and can help to identify the location of nerve irritation. Splinting the elbow in an appropriate way allows the nerve and the surrounding structures to rest and have relief from traction and compression. This method can be combined with local steroid injections for the relief of pain and swelling. Though steroid injections can have positive effects, caution has been used to avoid complications such as scarring and atrophy.

Avoiding symptom-provoking activities can be the most important aspect of treating cubital tunnel syndrome, although this may mean a cessation of work. Creating an effective treatment plan is challenging for professionals as the recovery period of nerves can be unpredictable. Ice application may also help to reduce pain and swelling and can be combined with gently applied active range of motion exercises.

Ultrasound therapy is also an option, but only when used appropriately and with caution as it is also shown to cause further nerve damage when used at an inappropriate intensity, slowing the speed of recovery.

Active range of motion exercises should be initiated within a range of comfort, with stretching also within tolerance, and only after pain levels have decreased.

Cubital Tunnel Syndrome Exercises to Relieve Pain

Purpose of Nerve Gliding Exercises

Inflammation or adhesions anywhere along the ulnar nerve path can cause the nerve to have limited mobility and essentially get stuck in one place.

These exercises help stretch the ulnar nerve and encourage movement through the cubital tunnel.

Elbow Flexion and Wrist Extension

Equipment needed: none

Nerve targeted: ulnar nerve

- Sit tall and reach the affected arm out to the side, level with your shoulder, with the hand facing the floor.

- Flex your hand and pull your fingers up toward the ceiling.

- Bend your arm and bring your hand toward your shoulders.

- Repeat slowly 5 times.

Head Tilt

Equipment needed: none

- Nerve targeted: ulnar nerve

- Sit tall and reach the affected arm out to the side with your elbow straight and arm level with your shoulder.

- Turn your hand up toward the ceiling.

- Tilt your head away from your hand until you feel a stretch.

- To increase the stretch, extend your fingers toward the floor.

- Return to the starting position and repeat slowly 5 times.

Arm Flexion in Front of Body

Equipment needed: none

Nerve targeted: ulnar nerve

- Sit tall and reach the affected arm straight out in front of you with your elbow straight and arm level with your shoulder.

- Extend your hand away from you, pointing your fingers toward the ground.

- Bend your elbow and bring your wrist toward your face.

- Repeat slowly 5-10 times.

A-OK

Equipment needed: none

Nerve targeted: ulnar nerve

- Sit tall and reach the affected arm out to the side, with the elbow straight and the arm level with your shoulder.

- Turn your hand up toward the ceiling.

- Touch your thumb to your first finger to make the “OK” sign.

- Bend your elbow and bring your hand toward your face, wrapping your fingers around your ear and jaw, placing your thumb and first finger over your eye like a mask.

- Hold for 3 seconds, then return to the starting position and repeat 5 times.

- Warnings

- Always consult your doctor before beginning a new exercise program. If these activities cause intense shooting pain, stop immediately and discuss them with your doctor.

These exercises may cause a temporary tingling or numbness in the arm or hand. If this feeling persists after rest, discontinue and seek help. In some cases, cubital tunnel syndrome is not alleviated by conservative measures and surgery may be required.

Takeaway

Nerve gliding exercises may help decrease pain associated with cubital tunnel syndrome. Repeat these exercises once a day, three to five times per week, or as tolerated.

FAQ

What are the symptoms of cubital tunnel syndrome?

Symptoms of cubital tunnel syndrome are:

Tingling and numbness in the ring and little fingers of the hand, especially with the elbow bent.

Hand pain.

clumsiness and poor grip because of weakened muscles in the hand and arm involved.

A severe pain in the inside elbow.

Muscle weakness

How do you fix a cubital tunnel?

Cubital Tunnel Syndrome Treatments: Taking an anti-inflammatory medication and being careful not to bump your elbow, as well as avoiding sitting with your elbow flexed for extended periods of time, will usually take care of it.

What is the best exercise for cubital tunnel syndrome?

Without creating too much agony, extend your arm out in front of you with your palm toward the sky and your elbow perfectly straight. Your fingers should be gently and carefully curled into a fist before being turned downward. Bend your elbow gently and softly, then slowly extend your arms once again.

Can cubital tunnel syndrome heal without surgery?

The degree of symptoms will determine the course of treatment; some may be managed without surgery.

Can cubital tunnel be cured?

If left untreated, the illness may result in irreversible nerve damage and disability. Cubital tunnel syndrome is typically curable without surgery, however in more extreme situations when there is substantial discomfort or impairment, surgery could be advised.

How long does the cubital tunnel last?

The hand and wrist strength may not recover for several months, and the numbness and tingling may get better more rapidly or slowly. After surgery, cubital tunnel syndrome symptoms can not go away entirely, particularly in more severe instances.

5 Comments