Perthes disease and Physiotherapy Management

- Perthes disease (LCPD) is an idiopathic juvenile avascular necrosis of the femoral head in a skeletally immature patient, i.e. children.

- The disease affects children from ages two to fourteen. The disease can lead to permanent deformity and premature osteoarthritis. It is five times more common in boys than in girls, however, it is likely to cause more extensive damage to the bone in girls. In 10% to 15% of all cases, both hips are affected.

- As the blood vessels around the femoral head disappear and cells die, the bone also dies and stops growing. When the healing process begins, new blood vessels begin to remove the dead bone.

- This leads to a decrease in bone mass and a weaker femoral head. It can also lead to deformity of the bone due to new tissue and bone replacing the necrotic bone.

- The bone death appears in the femoral head due to an interruption in blood supply. As bone death appears, the ball develops a fracture of the supporting bone. This fracture indicates the outset of bone reabsorption by the body. As bone is slowly absorbed, it is replaced by new tissue and bone.

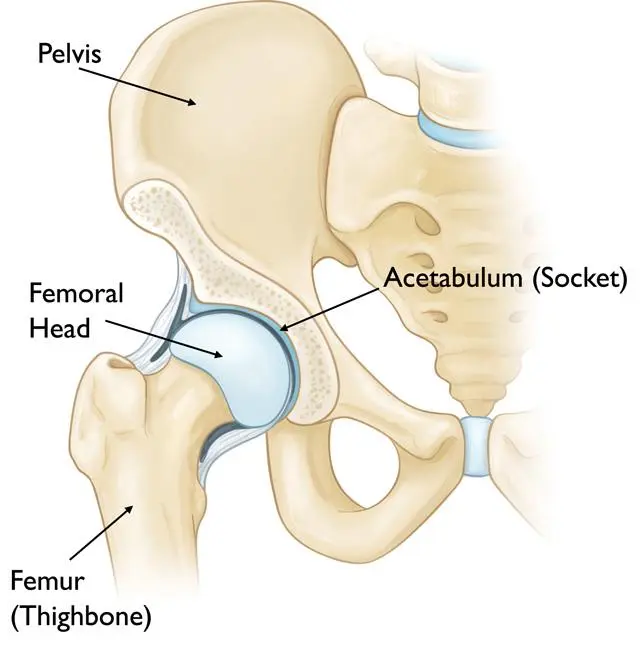

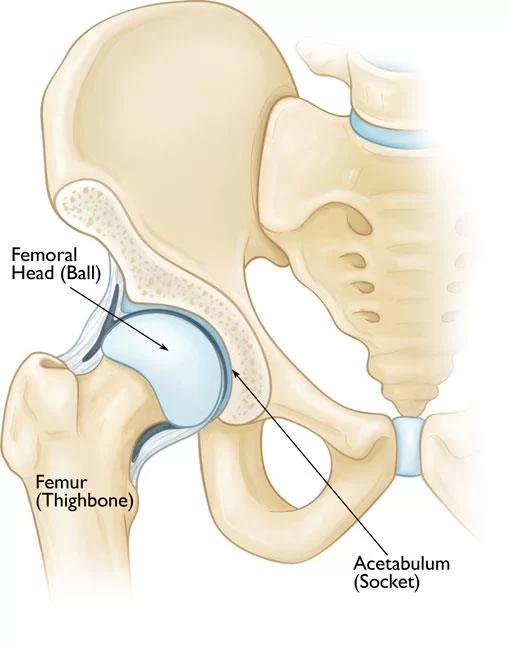

Anatomy related to Perthes disease

- The femoral head is supplied with blood from the medial circumflex femoral and lateral circumflex femoral arteries, which are branches of the profunda femoris artery.

- The medial femoral circumflex artery extends posteriorly and ascends proximally deep to the quadratus femoris muscle. At the level of the hip, it joins an arterial ring at the base of the femoral neck.

- The lateral femoral circumflex artery extends anteriorly and gives off an ascending branch, which also joins the arterial ring at the base of the femoral neck.

- This vascular ring gives rise to a group of vessels that run in the retinacular tissue inside the capsule to enter the femoral head at the base of the articular surface.

- There is also a small contribution from a small artery in the ligamentum teres to the top of the femoral head which is a branch of the posterior division of the obturator artery.

Causes of Perthes disease

- LCPD is an idiopathic disease, but a variety of theories about the underlying cause have been proposed since its discovery over a century ago, ranging from congenital to environmental and from traumatic to socio-economic causes. LCPD has been associated with thrombosis, fibrinolysis, and abnormal growth patterns of the bone.

- It has also been associated with an abnormality in the Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 Pathway, repeated microtrauma, or mechanical overloading related to hyperactivity of the child or very low birth weight or short body length at birth.

- Some studies suggest a genetic factor, i.e. a type II collagen mutation, and other studies report maternal smoking during pregnancy as well as other prenatal and perinatal risk factors.

- It maybe be that LCPD requires a set or subset of the aforementioned causes. As of yet, it is hard to discern which are determining or merely contributing factors to the onset of the disease.

Clinical Features of Perthes Disease

- Limp: A psoatic limp is typically present in these children secondary to weakness of the psoas major. The limp: is worse after physical activities and improves following periods of rest. The limp becomes more noticeable late in the day, after prolonged walking.

- Pain: The child is often in pain during the acute stages. The pain is usually worse late in the day and with greater activity. Night pains are frequent.

- ROM: The child will show a decrease in extension and abduction active ranges of motion. There is also a limited internal rotation in both flexion and extension in the early phase of the disease.

- Unusual high activity level: Children with LCPD are usually physically very active, and a significant percentage have true hyperactivity or attention deficit disorder.

- Abnormal growth patterns: General pattern: The forearms and hands are relatively short compared to the upper arm. The feet are relatively short compared to the tibia.

Stages of Perthes disease

- The progression of LCPD was classified over 4 stages by Waldenström in the early 20th century; Joseph et al. modified the Waldenström classification system by further classifying each of the first three stages into early (A) and late (B) substages in order to determine when various changes occur during the evolution of the disease.

- Stage I: Avascular necrosis or initial stage (± 1 year)

IA: Early

- Disruption of the blood flow causes osteonecrosis.

- Radiolucency of the femoral head.

IB: Late

- Flattening of the top of the femoral head

- A subchondral fracture line could be visible.

- Stage II: Fragmentation or resorptive stage (1 to 1 1/2 years)

IIA: Early

- The femoral head displays an irregular density

- Early fragmentation can be seen

IIB: Late

- Dead bone is resorbed causing a higher degree of fragmentation.

- The femoral head appears more flattened with an irregular outline

- May appear to subluxate.

- Stage III: Reossification stage (2-3 years)

IIIA: Early

- New porous bone is formed along the outer perimeter of the femoral head

- Density increases

- IIIB: Late

- The newly-formed bone gradually fills in towards the central area.

- The outline and shape of the femoral head become better defined

Stage IV: Healed

- The appearance of the bone in the femoral head looks similar to the normal side. It is homogeneous, however, can be enlarged (called coxa magna), flattened (coxa plana), and have a short, broad neck (coxa breva).

- The final shape of the femoral head at this stage (the degree of flattening or deformity) and how it fits the socket largely determines the long-term outcome.

Diagnosis of Perthes disease

- A MRI is usually obtained to confirm the diagnosis; however, x-rays can also be of use to determine femoral head positioning.

- Since LCPD has a variable end result, an imaging modality that can predict the outcome at the initial stage of the disease before significant deformity has occurred is ideal.

- The extent of femoral head involvement depicted by non-contrast and contrast MRI showed no correlation at the initial stage of LCPD, indicating that they are assessing two different components of the disease process. In the initial stage of LCPD, contrast MRI provided a clearer depiction of the area of involvement.

- To quantify femoral head deformity in patients with LCPD novel three-dimensional (3D) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) reconstruction and volume-based analysis can be used.

- The 3D MRI volume ratio method allows accurate quantification and demonstrated small changes (less than 10 percent) of the femoral head deformity in LCPD. This method may serve as a useful tool to evaluate the effects of treatment on femoral head shape.

Medical Treatment of Perthes Disease

- The approach to treatment is controversial. Prior to evaluating if a surgical intervention is necessary, there has to be a clear understanding of the disease prognosis.

- Approaches to treatment can be divided into conservative or operative treatments.

- Medications include non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) for pain and/or inflammation.

- Psychological factors are also considered. Persons with a history of LCPD are 1.5 times more likely to develop attention deficit disorders compared to their peers. They also have a higher risk of developing depression.

Physiotherapy management of Perthes disease

- There is no consensus concerning the possible benefits of physiotherapy in LCPD, or in which phase of the development of the health problem it should be used.

- Some studies mention physiotherapy as a pre-and/or postoperative intervention, while others consider it a form of conservative treatment associated with other treatments, such as skeletal traction, orthosis, and plaster cast.

- In studies comparing different treatments, physiotherapy was applied in children with a mild course of the disease. The characteristics of the patients were:

- Children with less than 50% femoral head necrosis (Catterall groups 1 or 2)

- Children with more than 50% femoral head necrosis, under six years, whose femoral headcover is good (>80%)

- Herring type A or B

- Salter Thompson type A

- For patients with a mild course, physiotherapy can produce improvement in articular range of motion, muscular strength, and articular dysfunction. The physiotherapeutic treatment included:

- Passive mobilizations for musculature stretching of the involved hip.

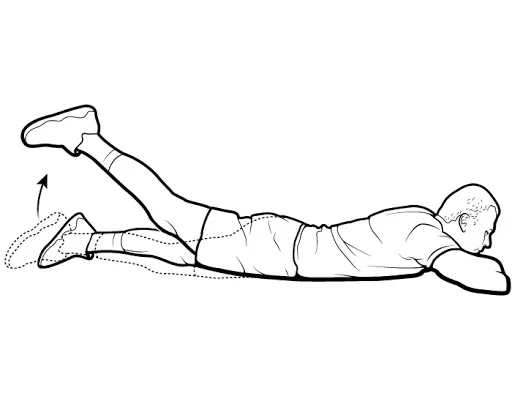

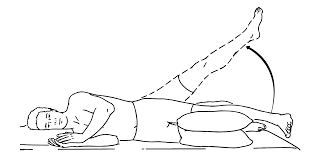

- Straight leg raise exercises, to strengthen the musculature of the hip involved for the flexion, extension, abduction, and adduction of muscles of the hip.

- They started with isometric exercises and after eight-session, isotonic exercises.

- A balance training initially on stable terrain, and later on unstable terrain.

- For children over 6 years at diagnosis with more than 50% of femoral head necrosis, proximal femoral varus osteotomy gave a significantly better outcome than orthosis and physiotherapy.

- There is an evidence-based care guideline concerning post-operative management of LCPD in children age 3 to 12 and an evidence-based care guideline for conservative management of LCPD in children age 3 to 12.

- These studies are mostly based on the ‘local consensus’ of the members of the LCPD team from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. These guidelines express the evidence regarding physical therapy (PT) treatment pathways, post-operatively, and conservative management.

Conservative management of Perthes diseases

- Physiotherapy interventions have been shown to improve ROM and strength in this patient population.

- Individuals who participate in supervised clinic visits demonstrate greater improvement in muscle strength, functional mobility, gait speed, and quality of exercise performance than those who receive a home exercise program alone or no instruction at all

- Individuals who receive regular positive feedback from a physical therapist are more likely to be compliant with a supplemental home exercise program.

- It is recommended that supervised physical therapy is supplemented with a customized written home exercise program in all phases of rehabilitation.

Improve ROM in Perthes disease : (see appendix 1 for exercise prescription)

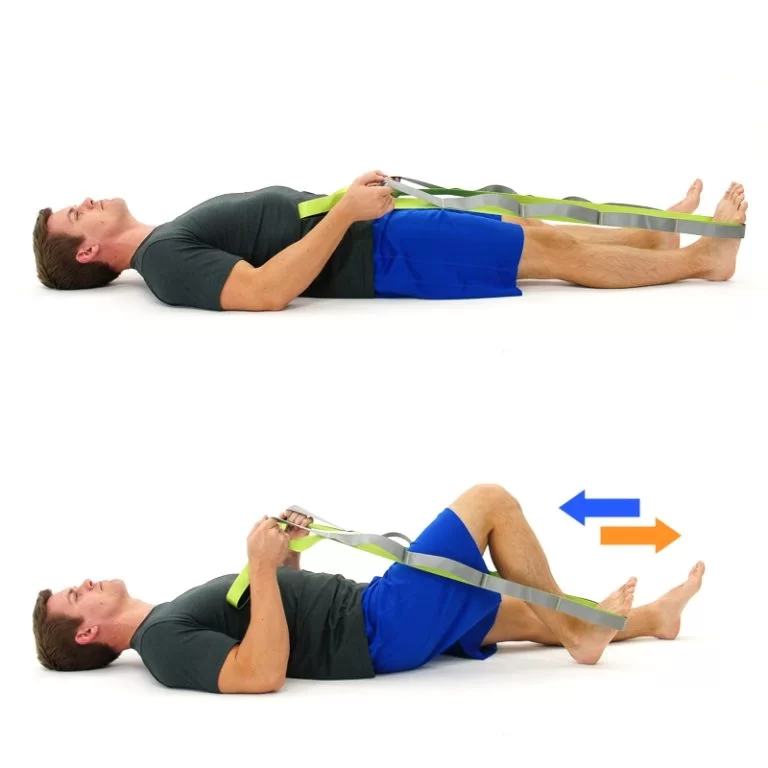

- A static stretch for lower extremity musculature)

- Dynamic ROM

- Perform AROM and AAROM (active assistive range of motion) following passive stretching to maintain newly gained ROM

- Improve strength

- Begin with isometric exercise and progress to isotonic exercises in a gravity lessened position with further progression to isotonic exercises against gravity. It is appropriate to include concentric and eccentric contractions.

- Begin with 2 sets of 10 to 15 repetitions of each exercise, with progression to 3 sets of each exercise to be used

- The local consensus would also do exercises to improve balance and gait and interventions to reduce pain.

- The hip overloading pattern should be avoided in children with LCPD. Gait training to unload the hip might become an integral component of conservative treatment in children with LCPD.

- Non-surgical treatment with a brace is a reliable alternative to surgical treatment in LCPD between 6 and 8 years of age at onset with Herring B involvement. However, they could not know whether the good results were influenced by the brace or stemmed from having a good prognosis of these patients.

Post-operative management of perthes disease

- The rehabilitation is described with reference to the various stages of rehabilitation.

Initial Phase (0-2 weeks post-cast removal)

Goals of the Initial Phase

- Minimize pain

- Hot pack for relaxation and pain management with stretching

- Cryotherapy

- Medication for pain

- Optimize ROM of hip, knee, and ankle

- Passive static stretch(A hot pack may be used, based on patient preference and comfort

- Dynamic ROM

- Perform AROM and AAROM following passive stretching to maintain newly gained ROM

- Increase strength for hip flexion, abduction, and extension and knee and ankle (see appendix 2 for exercises)

- Begin with isometric exercises at the hip and progress to isotonic exercises in a gravity-lessened position

- Begin with isometric exercises at the knee and ankle, progressing to isotonic exercises in a gravity-lessened position with further progression to isotonic exercises against gravity

- Begin with 2 sets of 10 to 15 repetitions of each exercise with progression to 3 sets of each exercise to be used

- Improve gait and functional mobility

- Follow the referring physician’s guidelines for WB status

- Transfer training and bed mobility to maximize independence with ADL’s

- Gait training with the appropriate assistive device, focusing on safety and independence.

- Improving skin integrity

- Scar massage and desensitization to minimize adhesions

- A warm bath to improve skin integrity following cast removal, if feasible in the home environment

- Warm whirlpool may be utilized if the patient is unable to safely utilize a warm bath for skin integrity management

- PT is supervised at a frequency of 2-3 times per week (weekly)

- Follow the referring physician’s guidelines for WB status

- Continue gait training with the appropriate assistive device focusing on safety and independence

- Begin slow walking in chest-deep pool water with arms submerged

- Improving Skin Integrity

- Continue with scar massage and desensitization

- PT is supervised at a frequency of 2-3 times per week (weekly)

- It is recommended that activities outside of PT are restricted at this time due to WB status. If the referring physician allows, swimming is permitted

Advanced Phase(6-12 weeks post-cast removal) :

Goals

- Minimize pain (see ‘initial phase’)

- optimize ROM and flexibility of the hip, knee, and ankle

- Increase the strength of the knee and hip, except for hip abductors, to at least 70% of the uninvolved lower extremity and increase the strength of the hip abductors to at least 60% of the uninvolved lower extremity due to mechanical disadvantage (4 + 5) (see appendix 2 for exercises)

- Isotonic exercises of the hip, knee, and ankle in gravity-lessened and against-gravity positions, including concentric and eccentric contractions

- WB and non-weight bearing (NWB) activities can be used in combination based on the patient’s ability and goals of the treatment session

- Begin upper extremity-supported functional dynamic single-limb activities (e.g. step-ups, side steps)

- Continue with double-limb closed chain exercises with resistance, progressing to single-limb closed chain exercises with light resistance if WB status allows

- Use of a stationary bike in an upright or recumbent position keeping the hip in less than 90 degrees of flexion

- Ambulation without the use of an assistive device or pain

- Negotiate stairs independently using a step to pattern with upper extremity (UE) support

- Improve balance to greater than 69% of the maximum Pediatric Balance Score (39/56) or single-limb stance of the uninvolved side

- Improving gait and functional mobility

- PT is supervised at a frequency of 1-2 time per week (weekly) Physical Therapy Management

- There is no consensus concerning the possible benefits of physiotherapy in LCPD, or in which phase of the development of the health problem it should be used.

- Some studies mention physiotherapy as a pre- and/or postoperative intervention, while others consider it a form of conservative treatment associated with other treatments, such as skeletal traction, orthosis, and plaster cast.

- In studies comparing different treatments, physiotherapy was applied in children with a mild course of the disease. The characteristics of the patients were:

- Children with less than 50% femoral head necrosis

- Children with more than 50% femoral head necrosis, under six years, whose femoral headcover is good (>80%)

- Herring type A or B

- Salter Thompson type A

- For patients with a mild course, physiotherapy can produce improvement in articular range of motion, muscular strength, and articular dysfunction. The physiotherapeutic treatment included:

- Passive mobilizations for musculature stretching of the involved hip.

- Straight leg raise exercises, to strengthen the musculature of the hip involved for the flexion, extension, abduction, and adduction of muscles of the hip.

- They started with isometric exercises and after eight-session, isotonic exercises.

- A balance training initially on stable terrain, and later on unstable terrain.

- For children over 6 years at diagnosis with more than 50% of femoral head necrosis, proximal femoral varus osteotomy gave a significantly better outcome than orthosis and physiotherapy.

- There is an evidence-based care guideline concerning post-operative management of LCPD in children age 3 to 12 and an evidence-based care guideline for conservative management of LCPD in children age 3 to 12.

- These studies are mostly based on the ‘local consensus’ of the members of the LCPD team from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. These guidelines express the evidence regarding physical therapy (PT) treatment pathways, post-operatively, and conservative management.

FAQs

What is the cause of Perthes disease?

Perthes’ disease causes are:

Your blood supplies oxygen and other nutrients to your bones. Blood flow to the femoral head is impaired in kids with Perthes disease. What brings about this is unknown. The femoral head’s bone cells deteriorate if they don’t receive enough oxygen and nutrients.

What is Perthes disease?

A rare childhood disorder affecting the hip joint is called Perthes disease. Lack of blood supply causes the bone in the “ball” (femur head) portion of the “ball and socket” hip joint to die. A new femoral head forms when the blood flow resumes. Time/observation, medication, physical therapy, casts, and surgery are among the forms of treatment.

What is the best treatment for Perthes disease?

Depending on the severity of the condition, Perthes’ disease may be treated with physiotherapy, crutches, plasters, or, in some cases, an operation that reforms the bone surrounding the hip joint.

Is Perthes disease genetic?

Typically, genetic factors do not induce Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease. In some circumstances, there is no recognized reason. Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease’s distinctive bone deformities are occasionally brought on by mutations in the COL2A1 gene.

What are exercises for Perthes disease?

stretching activities to improve hip muscle flexibility. Gait training is the process of learning a typical (walking) gait pattern. Activities to enhance coordination and balance. How to include low-impact exercises like walking and stationary cycling in your child’s daily routine.

3 Comments