Subtalar Joint Arthritis: Physiotherapy Management

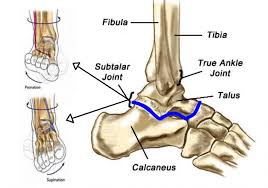

What is Subtalar Joint Arthritis?

Subtalar joint arthritis into degenerative changes in the cartilage of the subtalar joint. The most common cause of sub-talar arthritis is traumatic injury to the hindfoot which is commonly seen after a fracture to the calcaneus or talus.

Presenting symptoms of subtalar arthritis include pain and swelling in the hind-foot. Weight-bearing X-rays of the foot and ankle are primarily used to diagnose subtalar arthritis, but computed tomography (CT) can also be a useful tool in diagnosis.

It can occur at any age, and literally means “pain within a joint.” As a result, arthritis is a term used broadly to refer to a number of different conditions.

Anatomy of the subtalar joint:

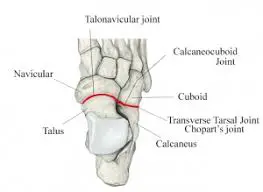

In a simplified way, one can divide the subtalar joint into two parts, an anterior and a posterior part.

Anteriorly, the talar head is located on the anterior and middle facets of the calcaneus, forming the acetabulum pedis with the posterior surface of the navicular bone.

However, it is important to mention that the talar head is not only supported by the articulating surfaces of the calcaneus and the navicular bone, but also by the ‘spring’ ligament.

This ligament complex plays a key role in stabilising the talar head. Insufficiency of this structure can lead to acquired flat foot deformity.

Posteriorly, the concave facet of the talus lies on the convex posterior facet of the calcaneus .

The size and shape of the three calcaneal facets vary between individuals. Both the anterior and middle facets are concave, while the posterior facet is the calcaneal.

The posterior facet is larger compared with the middle and the anterior facets and is separated from the other two facets by the interosseous calcaneal ligament .

For the anterior and middle calcaneal facets, different anatomical variations have been described in the literature.

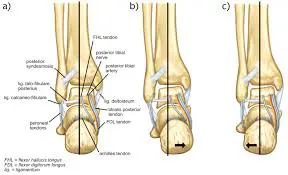

Studies found that 42% have a combined anterior and middle facet in an ovoid form, 22% a ‘bean’ form and 36% have a complete separation.6 The sustentaculum tali is formed by the middle calcaneal facet (dorsal surface) and provides a sliding surface for three tendons (plantar surface): the tibialis posterior, flexor hallucis longus and flexor digitorum longus tendons.3 Subtalar joint .

The ligaments around the subtalar joint can be distinguished as intrinsic (cervical ligament, interosseous talo-calcaneal ligament) and extrinsic ligaments (calcaneo-fibular ligament, tibio-calcaneal part of the deltoid ligament).

Malfunction of the interosseous talo-calcaneal ligament, especially in combination with failure of the anterior talo-fibular ligament, leads to an unphysiological anterolateral rotation of the talus during gait .

As a result, subtalar joint and secondary ankle joint instability may occur.

The importance of the calcaneo-fibular ligament for subtalar stabilisation is still being debated.

In both cadaveric and clinical studies, where the calcaneo-fibular ligament had failed, an increase of subtalar movement and instability was observed .

In contrast, Michelson et al13 could not find any changes in subtalar joint stability during the stance phase, after transection of all lateral ligaments, including the calcaneo-fibular ligament.

A further structure that affects the subtalar joint.

in terms of stability and movement is the inferior extensor retinaculum. Acting like a pulley, movement of the extensor tendons influences the subtalar stability and movement.

Anatomy related to Subtalar joint arthritis

The talus is the only tarsal bone with no muscular or tendinous attachments. It is oriented obliquely on the anterior surface of the calcaneus. The irregular shape of the talus can be defined by the head, neck, and body.

Talar body:

The superior talar body has three articulating surfaces with the tibia (medial and central) and fibula (lateral) making up the ankle joint.

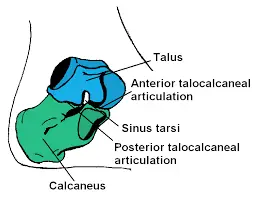

The inferior surface of the body has two articular areas, the posterior and the middle, which is separated by a deep groove, the sulcus tali.

This groove runs from proximal medial to distal lateral and, together with a similar groove in the calcaneus, forms the sinus tarsi, which serves as attachment points for the interosseous talocalcaneal ligament.

The concave posterior articular surface articulates with the convex surface of the posterior facet on the calcaneus.

The slightly convex middle articular surface articulates with the dorsal surface of the sustentaculum tali of the calcaneus.

The posterior body has a small medial and larger lateral process, flanking a groove for the flexor hallucis longus tendon.

The lateral process serves as an attachment point for the posterior talocalcaneal ligament.

Talar neck:

The talar neck consists of the constricted portion of the talus between the body and the head. It has roughened upper and medial surfaces for ligamentous attachments. Its lateral concave surface is continuous with the sinus tarsi.

Talar head:

Distally, there is a large, oval, convex articular surface that is congruent with the concave navicular surface.

The inferior surface has two facets: The medial facet rests on the plantar calcaneonavicular ligament adjacent to the middle calcaneal facet, and the lateral facet (or anterior calcaneal articular surface) is a flattened surface that articulates with the facet on the upper surface of the anterior part of the calcaneus.

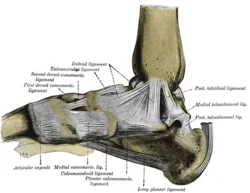

Ligaments:

Ligaments that contribute to subtalar stability can be divided into three layers.

The superficial layer consists of the calcaneofibular, lateral talocalcaneal, medial talocalcaneal, and posterior talocalcaneal ligaments and the lateral root of the inferior extensor retinaculum.

The intermediate layer consists of the cervical (or anterior talocalcaneal) ligament and the intermediate root of the inferior extensor retinaculum.

The deep layer includes the strong interosseous talocalcaneal ligament and the medial root of the inferior extensor retinaculum.

A capsule encompasses a synovial membrane that runs continuously with the talocalcaneonavicular and calcaneocuboid joints.

Structure:

The talus is oriented slightly obliquely on the anterior surface of the calcaneus.

There are two points of articulation between the two bones: one anteriorly and one posteriorly:-

At the anterior talocalcaneal articulation, a convex area of the talus fits on a concave surface of the calcaneus.

The posterior talocalcaneal articulation is formed by a concave surface of the talus and a convex surface of the calcaneus.

There are three articulating facets between the talus and the calcaneus, delineated as the anterior, middle and posterior facets.

The sustentaculum tali forms the floor of middle facet, and the anterior facet articulates with the head of the talus, and sits lateral and congruent to the middle facet.

The posterior facet is the largest of the three, and separated from the others by the tarsal canal.

Ligaments and membranes:

The main ligament of the joint is the interosseous talocalcaneal ligament, a thick, strong band of two partially joined fibers that bind the talus and calcaneus.

It runs through the sinus tarsi, a canal between the articulations of the two bones.

There are four additional ligaments that form weaker connections between the talus and calcaneus.

The anterior talocalcaneal ligament (or anterior interosseous ligament) attaches at the neck of the talus on the front and lateral surfaces to the superior calcaneus.

The short band of the posterior talocalcaneal ligament extends from the lateral tubercle of the talus to the upper medial calcaneus.

The short, strong lateral talocalcaneal ligament connects from the lateral talus under the fibular facet to the lateral calcaneus, and runs parallel to the calcaneofibular ligament.

The medial talocalcaneal ligament extends from the medial tubercle of the talus to the sustentaculum tali on the medial surface of the calcaneus.

A synovial membrane lines the capsule of the joint, and the joint is wrapped in a capsule of short fibers that are continuous with the talocalcaneonavicular and calcaneocuboid joints of the foot.

Function of the Subtalar Joint:

Walking is a sophisticated function for which we give little thought. From the perspective of the ankle and foot, this requires three distinct actions :

We need to be able to roll the foot away from the midline of the body (supination) and toward the midline of the body (pronation).

We need to be able to flex the foot upward (dorsal flexion) and downward (plantar flexion).

We need to be able to rotate our foot laterally away from the midline (abduction) and toward the midline (adduction).

Doing so together not only provides us the means to walk, it allows us to adapt to shifting terrain and to absorb shock as the force of an impact is redistributed according to the position of the bones.

With regard to the subtalar joint, its articulated structure enables the inversion or eversion of your foot.

While inversion and eversion are components of pronation and supination, respectively, they specifically involve the hindfoot rather than the entire foot.

With inversion, you rotate your ankle inward.

With eversion, you rotate it outward.

By contrast, pronation involves inversion in association with the collapse of the midfoot into the arch.

Supination involves eversion as the arch is lifted and the midfoot rolls to the side.

The subtalar joint plays no role in either dorsal or plantar flexion.

Causes of Subtalar joint arthritis:

Trauma to the region.

Frequent sprains to the joint complex.

Fractures into the joint.

Calcaneal fractures.

Talar fractures.

Abnormal bone connections (tarsal coalitions).

Vascular necrosis of the talus.

Signs and Symptoms:

Progressive loss of motion of the subtalar joint.

The difficulty with activities or uneven surfaces.

The difficulty with turning the foot down and in or up and out.

Diffuse swelling on the outside of the rear foot.

May be associated with spasm of the muscles on the outside of the leg. :-

History:

The common reasons for patient’s presenting to the foot and ankle clinic are: Pain, swelling, deformity, stiffness, instability and/or abnormal gait.

For new patients or when the diagnosis has not been confirmed before, we recommend that the examiner should not read the previous notes prior seeing the patient.

This good practice allows the examiner to have more lateral thinking, with fresh eyes looking into the problem.

Pain:

Ask the patient to finger point to the exact site of the maximum pain. If the pain is diffuse and not localized to one spot, try to identify the area/side of maximum discomfort.

Correlate the site with the anatomical location as described. Ask about the radiation of pain and its quality or nature of it (sharp, dull, or burning), whether it is related to weight bearing (degenerative changes, stress fracture, or Inflammatory conditions like plantar fasciitis), the radiation (towards the toes or up the leg), the severity of the pain (0-10), prevents activity, waking up during the night, time (early morning or night pain which disturbs the sleep), duration, pattern (constant/intermittent), aggravating factors (like walking distance, walking on the flat or uneven floor; Going up and down the stairs; relation with shoes), and any alleviating factors (rest, analgesia, preferred type of footwear).

The chronicity and the severity of the pain can help to establish whether there is an element of central sensitization where the patient becomes more sensitive and experiences more pain with less provocation. Factors like sleep deprivation and depression can drive central sensitization.

Finally, it is important to clarify what is the patients’ beliefs about their foot pain.

Deformity:

Enquire about the duration and when the patient or their family member first noticed the deformity, which area it involves, whether is it progressing, and whether it is associated with other symptoms (for example, skin ulcer, pain, recurrent infection, rapid wear of shoes, or cosmetic).

Swelling:

It is important to establish whether the swelling is localized to one area or the whole leg or ankle, whether it is uni- or bilateral, associated with activities, as well as the frequency and duration of swelling.

Generalized bilateral swelling that involves the whole foot and ankle is usually related to more systematic pathology, such as cardiac or renal problems.

Swelling which includes the area only around the ankle joint may be related to the tibio-talar joint (for example, degenerative changes or inflammatory arthropathy).

On the other hand, localized swelling is more likely to result from a specific local pathology.

As an example, swelling anterior to the distal fibula may indicate chronic injury of the anterior inferior tibio fibular ligament (ATFL), and swelling posterior to the distal fibula may indicate peroneal tendon pathology.

Acute painful or painless swelling with or without the deformity of the midfoot deformity could result from Charcot neuropathy.

Instability:

Enquire as to when the first episode of instability or sprain occurred, how often it happens, and what can precipitate it.

History of trauma:

History of trauma with details of immediate symptoms and treatment, surgery, injections, or infection with date and details of any identified.

Associated symptoms:

It is important to look out for red flags and symptoms such as night sweating, temperature, or weight loss, which may be related to an infection or neoplasm.

Neurological symptoms like numbness, limb weaknesses, or burning sensation are usually related either to spinal problems or peripheral neuropathy.

General medical history:

Important key points not to be missed in general medical history.

Age

Occupation

Participation in sports

History of lower back pain

History of problems with other joints (for example, hip and knee)

Diabetes

Peripheral neuropathy

Peripheral vascular disease

Inflammatory arthropathy

Rheumatoid arthritis

Clinical Examination:

The examination begins from the first moment of meeting the patient by observing the gait and whether he/she uses any walking aids.

The patient should be adequately exposed and ideally, patients should wear shorts with bare feet. Ask for a chaperone if appropriate.

Inspection of the patient’s footwear, insole, and walking aides

Start by examining the patient’s shoes and whether they are commercial or surgical shoes. Look at the pattern of the wear, which usually involves the outside of the shoe heel.

Different patterns of wear indicate abnormal contact of the foot with the ground. Early lateral, proximal, and mid-shoe wear, indicates a supination deformity; wear on the medial border indicates a pronation deformity.

In case of the absence of any wear, it may simply reflect a new or unused pair of foot wear. Look for any orthosis or walking aides.

Inspect any insole and ask the patient which type of insole is comfortable and which type is painful.

Examination in a standing position:

In most clinical settings the patient is sitting on the chair at the start of the examination.

First ask the patient to stand up, and assess the alignment of the lower limbs as a whole.

In particular look for any excessive varus or valgus knee deformity. Inspect the alignment of the spine in case of scoliosis, and look for any pelvic tilt. Inspect for any thigh or calf muscle wasting.

Look from the side for the feet arches (is there any pes cavus or pes planus), any swelling or scars.

Inspect for any big toe deformity (hallux valgus, hallux valgus interphalangeus, or hallus varus), or lesser toe deformity (mallet toe, hammer toes, claw toes).

In a normal ankle, you should not be able to see the heel pad on the medial side when you inspect from the front.

If this was visible then it is called the “peek a boo” sign which exists with pes cavus.

It is important to compare both sides as a false-positive sign may be caused by a very large heel pad or significant metatarsus adductus.

Inspect the ankle from the back for any bony bumps like a calcaneal boss. The normal ankle alignment is neutral.

Also, notice if there is a “too many toes” sign. In a normal foot, you should not be able to see more than 5th and 4th toes when you look at it from behind.

If there were more toes visible (3rd or 3rd and 2nd), then it is called a “too many toes” sign which can indicate an increased heel valgus angle.

Ask the patient to stand on tiptoes. Both ankles should turn into varus. This indicates normal subtalar movement and, in the case of flat feet, if a medial arch forms on standing on tiptoes then this is a flexible pes planus.

Gait: Enquire if the patient can walk without support and be prepared to provide support for elderly patients and those who may be unsteady on their feet.

Ask the patient to walk as per their normal gait. Observing the gait from the front and the back helps to assess the shoulder and pelvic tilt.

Looking at the hip movements, knee movements, initial contact, three rockers, stride length, cadence, and analgesia.

The patient should then be asked to walk on his/her tiptoes, then heels, inner borders, and finally the outer borders of the feet.

Examination in a sitting position:

By this stage, a fair idea of the possible diagnosis may have been established.

Hence, you should be able to direct the rest of the examination accordingly.

We recommend at this stage to ask the patient to sit on the examining couch, with the legs hanging loosely from the side.

Raise the bed so the patient’s foot is at the level of the examiner’s hand, and sit on a chair opposite the patient.

Look:

Start with meticulous inspection of the sole then the rest of the foot. Look for skin discoloration, scars, ulcers, lack of hair (circulatory changes), nails, and skin thickening (callosity), hard/soft corns, and any signs of infection.

Feel:

First ask the patient if there are any areas that are painful to touch, so you can try to avoid causing pain during the examination.

Then you start with a gentle feel of the skin temperature, always comparing to the other side.

The second part of the palpation is to establish the area of tenderness. Always follow a systematic method of palpation so you will not miss any part.

We recommend to start the palpation for tenderness from proximal fibula, Achilles tendon, distal fibula, peroneal tendons, PTFL, CFL, ATFL, AITFL, Sinus tarsi, Calcaneum, Calcaneocuboid (CC) joint, Cuboid, lesser Metatarsals, Phalanges, 1st IP and MTP joint, 1st ray, TMT joints, Cuneiforms, Navicular, TN joint, Talus, Ankle joint, Medial malleolus, Tibialis post, Tibialis anterior, extensors and other flexors and finally plantar fascia.

Move:

Start with active movement by asking the patient to perform dorsiflexion, plantar flexion, inversion, and eversion. Always compare both sides.

This will be followed by passive movement of dorsiflexion: As the patient is already sitting, the knee is flexed to 90 degrees then repeat the test with the knee straight (Silfverskiold test).

Keep the foot in a neutral position (0 degrees of inversion and eversion), hold the back of the leg with one hand, and use the palm of the other hand to push the sole of the examined foot.

Now move the palm of the hand to the dorsum of the examined foot to produce the passive plantar flexion.

Supination and pronation are tri-planar movements. Supination is the combination of Inversion, Plantarflexion and adduction. Pronation is the combination of Eversion, Dorsiflexion, and Abduction.

Inversion: Place one hand over the back of the leg use your other hand to grasp the calcaneus between your index finger and thumb and use your forearm to fully dorsiflex and lock the talus in the ankle.

Rotate the calcaneus in a medial direction to test for inversion and move your hand in a lateral direction to test for Eversion.

Midfoot movements:

Stabilize the calcaneus and talus with one hand and use the other hand to move the foot medially to test for Adduction). Move the foot laterally to test for abduction.

It is also important to examine the motion of the midfoot (transverse tarsal joint) on the sagittal plane (especially for patients with end-stage ankle arthritis).

The motion of the 1st TMT joint should be examined as well (for patients with hallux valgus or flexible flatfoot).

Forefoot movements (metatarsophalangeal and interphalangeal joints):

You should test the movement in each joint separately. If there is any deformity, try to find whether it is correctable or not (for example, a fixed flexion deformity).

The examination of muscular function and the special tests should be the next step of the assessment.

The strength of each muscle is assessed using the Medical Research Council (MRC).

Biomechanics of the subtalar joint:

Subtalar joint movement and axis of rotation are difficult to understand. Due to the convex posterior facet of the calcaneus and the corresponding concave facet of the talus, subtalar joint movement can be described as rotation, translation, or a combination of both.

Manter15 described a helical subtalar joint movement based on the helicoid contour of the posterior calcaneal facet.

According to these findings, for every 10° of rotation around the subtalar axis, the talus advances 1.5 mm.

However, Inman2 questioned this finding. In his cadaver study, half of the specimens showed a screw-like movement, while the other half showed translation in different directions or only in rotation.

Regarding the subtalar joint axis, Inman2 described an average inclination of 42° in the sagittal plane and 23° medial deviation in the axial plane when relating to the long axis of the foot.

However, the axis of the subtalar joint movement is reported to have a high variability in the literature.

This may be due to several factors, one of which is the method used for its determination.

While the axis was primarily determined using static radiographic images, in vivo studies were performed later on, followed by the use of magnetic resonance tomographic images in recent years.

Clinically, subtalar joint movement is classified as inversion-eversion. The other components, e.g. anteroposterior (AP) and mediolateral translation are not assessable on clinical examination.

The range of movement is in the range of 25° to 30° in inversion and 5° to 10° in eversion, respectively.

The high variability of the range of movement found in the literature can be explained when considering the different techniques used for its determination.

Furthermore, the position of the ankle joint also affects subtalar movement, for example, dorsal extension of the ankle joint decreases subtalar movement.

Several tendons cross the subtalar joint to balance the ankle in the stance phase and during gait.

Their function is dependent on the relation of the tendons to the subtalar joint axis.

The extensor halluces longus, extensor digitorum longus, and peroneus longus/brevis belong to the evertors. The tibialis posterior, flexor digitorum longus, flexor hallucis longus, and tibialis anterior are considered to be investors.

The moment arm of the tendons and thus the amount of force translated by the tendons is dependent on the subtalar joint position.

The tibialis posterior and the peroneus longus are the strongest invertor and evertors, respectively. Interestingly, the triceps surae have a slight inversion function while the ankle joint is in flexion/inversion and may change to an evertor when the subtalar joint is in eversion.

Pathogenesis of Subtalar joint arthritis:

Isolated subtalar arthritis can result from :

-Trauma (calcaneal/talus fractures)

-Primary talocalcaneal arthritis (instability/deformity)

-Symptomatic residual congenital deformity (talocalcaneal coalition)

-Posterior tibial tendon dysfunction

-Inflammatory arthritis isolated to the subtalar joint 3.

In a review of subtalar arthrodesis, Davies et al reported on 92 patients with 95 feet requiring fusion, with 67% for post-traumatic arthritis, 23% for primary osteoarthrosis, 5.3% for a tarsal coalition, and 4.2% for inflammatory joint disease.4

Post-traumatic arthritis often requires subtalar arthrodesis :

-Of the calcaneal fractures treated operatively, 3.3% require subtalar fusion.

-Of the calcaneal fractures treated non-operatively, 16.9% require subtalar fusion.

-Non-operatively treated calcaneal fractures are 5.5 times more likely than operatively treated calcaneal fractures to require a subtalar arthrodesis.

-Talar neck fractures have an incidence of arthrosis of 30% to 90%, mostly subtalar.

-The rate of arthrodesis following fixation of a talus fracture ranges from 10% to 15%.

-Anatomic variations of the sustentaculum tali may predispose patients to instability and formation of talocalcaneal arthritis.

An anatomic cadaver study examining sustentaculum tali morphology and associated arthritis found significantly higher rates of arthritis in specimens with long continuous facets (65%) and medial-only facets (50%) when compared to separate anterior and medial facets (35%).

It was hypothesized that these morphological variations of the sustentaculum tali may predispose people to joint instability, ligamentous laxity, and the development of arthritic changes in the subtalar joint.

Classification (Staging):

Stage 0 – Normal joint or subchondral sclerosis

Stage 1 – Presence of osteophytes without joint-space narrowing

Stage 2 – Joint-space narrowing with or without osteophytes

Stage 3 – Subtotal or total disappearance or deformation of joint space

Physical Examination:

The patient history should include the exact nature, location, duration, and progression of symptoms, as well as aggravating and alleviating factors and prior therapeutic interventions.

Equally important is to identify the extent of disability and the goals/expectations that the patient has for any treatment.

Patients with symptomatic hindfoot arthritis often report pain, swelling, and stiffness of the foot that is aggravated by ambulating on uneven ground.

Subtalar joint pain is often felt in the lateral hindfoot and may be accompanied by feelings of instability, catching, or locking. Pain often gets better with rest or by wearing high-top shoes.

Physical examination begins with observation of barefoot alignment during standing and walking.

Gait disturbances, the position of the foot, and overall alignment should be assessed. Excessive hindfoot varus or valgus and areas of swelling and tenderness should be noted.

The joints of the hindfoot and midfoot should be assessed for motion and generation of any pain. Specific findings to the subtalar joint include hindfoot swelling, tenderness within the sinus tarsi, pain with inversion/eversion of the hindfoot, limited range of motion of the subtalar joint, and an antalgic gait.

The heel cord and gastrocnemius should be evaluated for tightness. As always, a detailed neurovascular examination should be performed to determine weakness, loss of sensation, and the presence of pulses.

Subtalar Joint Problems:

As vital as the subtalar joint is to mobility, it is vulnerable to wear and tear, trauma (especially from high-impact activity), and other joint-specific disorders.

The damage can often be deeply felt and difficult to pinpoint without imaging tests, such as ultrasound.

Any damage done to the subtalar joint, including any connective tissues that support it, can trigger pain, lead to foot deformity (often permanent), and affect your gait and mobility. The damage may be broadly described as capsular or non-capsular.

Capsular disorders are those in which the subtalar joint is primarily involved and intrinsically impairs how the joint is meant to function. Among the examples:

Gout is a type of arthritis that commonly affects the first metatarsophalangeal joint (the big toe), but can also cause inflammation and pain in the subtalar joint.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis is a type of pediatric arthritis with no known cause in which the subtalar joint is often the first joint affected.

Osteoarthritis is the wear-and-tear form of arthritis that is often caused by a previous joint injury, such as a fracture.

Rheumatoid arthritis is the autoimmune form of arthritis in which the body’s immune system primarily attacks joint tissues. The ankle and foot are common sites of involvement.

Non-capsular disorders are those in which the subtalar joint is indirectly or collaterally affected due to defects or injuries of the foot or ankle. Among the examples:

Subtalar instability involves a lateral weakness in which the ankle can suddenly “give way.” This can lead to the twisting of an ankle or chronic inflammation due to extreme pressure placed on the lateral ligament.

Subtalar dislocation, often described as “basketball foot,” typically occurs if you land hard on the inside or outside of your foot.

Pes planus, also known as “flat feet,” is a collapsed arch. It usually develops during childhood due to overpronation and can sometimes cause extreme pain if the foot is not structurally supported.

Pes cavus, also referred to as a high instep, is an exaggerated arch of the foot that is often caused by a neurological disorder that alters its structure. This can lead to a severe restriction of movement, pain, and disability.

Polyarthropathy is a condition where pain and inflammation occur in multiple joints. While arthritis is a common cause, it may be secondary to conditions like a collagen-vascular disease (such as lupus or scleroderma), a regional infection, and Lyme disease.

Tarsal coalition is a fusion of the bones in the hindfoot. It is characterized by a limited range of motion, pain, and a rigid, flat foot. It may occur during fetal development when the bones of the foot fail to differentiate, but can also be caused by arthritis, an infection, or a serious injury to the heel.

Diagnosis of Subtalar joint arthritis:

Injuries or disorders of the ankle and foot can be diagnosed and treated by a podiatrist (foot doctor) or an orthopedist (bone, joint, and muscle specialist).

Diagnosis typically involves a physical examination, a review of your medical history, and imaging tests, such as an X-ray, ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) scan, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan.

In some cases, multiple imaging tests may be needed to reveal hidden fractures (known as occult fractures) frequently missed in the heel area.

Blood tests may be ordered to measure inflammatory markers suggestive of infection or to check for antibodies associated with rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, or other autoimmune disorders.

If a specific infection is suspected, a bacterial culture or antibody-based viral blood test may be performed.

Tests can also be used to differentiate subtalar joint disorders from other conditions that cause pain or inflammation in the ankle and heel area. These include:

Bursitis:

inflammation of the cushioning pockets between joints (called bursa) that often co-occurs with capsular disorders

Lumbar radiculopathy:

pinched nerve in the lower back that triggers buttock or leg pain

Posterior tibial tendinitis:

inflammation of the tendon around the inner ankle that causes pain in the inner foot and heel

Primary or secondary bone cancers:

often manifest with joint and bone pain

Tarsal tunnel syndrome:

pinched nerve in the inner ankle that can trigger heel pain

Treatment of Subtalar joint arthritis:

Post-Operative Course:

Day 1:

Foot wrapped in bulky bandage and splint, ice, elevate, take pain medication

Expect numbness in the foot for 12- 24 hours then pain

Bloody drainage is to be expected

Do not change the bandage

Day 14:

The dressing is changed, x-rays taken and a boot is applied

No weight bearing for about 6 – 8 weeks

6 weeks:

The boot is removed, and x-rays are taken

Continue full activities now in the boot and a gradual increase in weight bearing is initiated, with pain as a guide

12 weeks:

Start an exercise program

Orthotic arch supports are likely ordered

Non-Operative Treatment of Subtalar joint arthritis:

Non-operative treatment focuses on limiting the amount of loading and movement at the subtalar joint and masking the pain. Non-operative treatment involves some trial and error on the part of the patient to see what strategies are most effective. Non-operative treatments include:

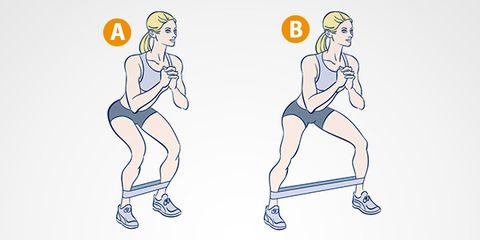

Activity Modification:

Limiting standing and walking, particularly on uneven terrain, will help limit the exacerbation of symptoms from subtalar arthritis. Use of an exercise bike or swimming as a form of aerobic exercise instead of walking or running will likely be beneficial as it allows for a good workout with much less loading through the subtalar joint.

The back part of the foot is subject to forces equivalent to 3-5x body weight during daily activities, so losing even a moderate amount of weight can substantially decrease the forces going through the arthritic joint.

Comfort Shoes:

The use of comfort shoes, including adding a shock absorber in the heel, can help decrease the repetitive loading through the subtalar joint.

Ankle Bracing:

Use of an ankle brace, such as an ankle lacer, or even taping the ankle and hindfoot can be helpful because it serves to limit motion through the arthritic subtalar joint.

Icing and Elevation after Activity :

Elevating the leg and placing a bag of ice around the ankle and hindfoot after activity can help to decrease pain and swelling. Ice should only be applied for 10-15 minutes at a time.

Anti-inflammatory medication (NSAIDs):

If there are no contra-indications, NSAIDs can help decrease a patient’s arthritis symptoms

Tylenol:

Plain Tylenol (acetaminophen) taken 2-3 times a day can help reduce the pain from subtalar arthritis. It may not be as effective as anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs), but it works via a different mechanism so it may have an additive effect. It should not be taken by anyone with liver problems

Glucosamine Sulfate:

Although it has not been shown to be beneficial in long-term studies, many people report improved symptom control when they take glucosamine sulfate. It needs to be taken daily for 6-8 weeks for any benefit to be seen.

Corticosteroid Injections:

Pain relief from corticosteroid injections will tend to be temporary.

Hyaluronic Acid Injections (HA):

Injections of HA have shown some success in the knee joint, but the results in the subtalar joint have not been demonstrated.

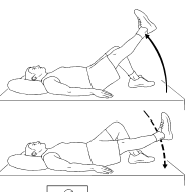

Self-administered strengthening and stretching programs:

Exercise to keep the muscles of the foot as strong as possible, and to keep the joint moving through a gentle range of motion, may be helpful.

Operative Treatment:

Operative treatment is usually reserved for extensive subtalar arthritis that has failed non-operative management. Occasionally patients will be noted to have an isolated area of damage to the subtalar joint or will have a loose body which can be addressed by cleaning out (debriding) the subtalar joint, either arthroscopically or more commonly by opening the joint.

However, in most instances, patients with subtalar arthritis have lost significant cartilage and need to have the subtalar joint fused

A subtalar fusion is not to be confused with a subtalar arthrosis (placing a plug in the subtalar joint), which is not appropriate for treating subtalar arthritis.

Subtalar Fusion (Arthrodesis):

Fusing the subtalar joint is an effective treatment option for patients with significant subtalar arthritis that has failed non-operative management.

When considering subtalar fusion, realize you are trading painful motion for pain relief. Even though the foot will lose side-to-side motion, often patients are able to be much more active because they have substantially less pain.

A subtalar fusion is performed by cleaning out the remnants of cartilage from the joint and putting screws and bone grafts across the joint.

The goal is the union of the surfaces between the talus and the calcaneus (heel bone). This may require 6-10 weeks of activity restriction, and walking with crutches or using a knee scooter.

Once healed, weight-bearing is progressed until the patient is able to walk in regular shoes without the use of crutches. Physical therapy is important to improve ankle motion and balance.

Patients can expect a significant improvement in their ability to walk by 3 to 4 months after surgery but, may not reach maximal improvement until 12-18 months after surgery.

Conservative Treatment:

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and/or analgesics

Physical therapy for range of motion, strengthening, and proprioception

Activity modification to help avoid painful activities

Braces, shoe modifications, orthotics, or patellar tendon bearing brace with the following goals:

Limit painful joint motion

Accommodate rigid deformity

Correct flexible deformity

Relieve pressure points

Subtalar joint injections

FAQ

How do you treat arthritis in a subtalar joint?

Medical treatment involves:

1) By using comfort shoes, bracing the hindfoot, and controlling weight, one can reduce the amount of movement and loading via the subtalar joint.

2) Changing one’s activities, such as walking and standing less, especially on uneven ground

3) using NSAIDs to reduce the discomfort

Is subtalar arthritis permanent?

Gait and mobility problems can result from problems with the subtalar joint, especially while walking on uneven terrain. Damage to the subtalar joint may become irreversible if left untreated.

Is subtalar arthritis curable?

Subtalar arthritis has no known cure, yet there are several ways to manage it. It’s critical to get assistance as soon as possible to ensure that therapy can start right away. Subtalar arthritis patients may manage their pain, remain active, and lead happy lives with the right care, many of them without requiring surgery.

Can the subtalar joint heal on its own?

Injury to the subtalar joint may result in irreversible foot injury if left untreated. If you see any of the following symptoms: increasing pain, redness, swelling, bruises, or severe difficulties walking, you should get medical attention once.

What are the complications of subtalar arthritis?

The development of neighboring arthritic joint disease, namely affecting the talonavicular and calcaneocuboid joints, is the primary long-term consequence after a subtalar fusion. The primary short-term issue is nonunion, or the failure of the bones to fuse together.

One Comment