Maitland Mobilization Technique

What is the Maitland Mobilization technique?

The Maitland Concept of Manipulative Physiotherapy, often referred to as the Maitland Approach, places a strong emphasis on a specialized mindset, ongoing evaluation and assessment, and the intricate art of manipulative physiotherapy. This approach involves the precise understanding of when, how, and which techniques to apply, all customized to suit each patient’s needs. Central to this concept is an unwavering dedication to the well-being of the patient.

The Maitland concept finds its application in both peripheral and spinal joint treatments, with each requiring a detailed technical explanation and differing in terms of techniques and outcomes. Nonetheless, the underlying theoretical framework remains largely consistent for both types of treatment.

The concept derives its name from the pioneering work of Geoffrey Maitland, who is widely recognized as a trailblazer in the field of musculoskeletal physiotherapy. Alongside a group of esteemed colleagues, Maitland significantly contributed to the advancement of this specialized area of physiotherapy.

What is Manual Therapy?

“Manual therapy” can be broadly defined as the skillful use of hands to facilitate healing and therapeutic effects, encompassing hands-on techniques aimed at fostering well-being.

Numerous disciplines encompass the practice of manual therapy to address and alleviate various pathologies and dysfunctions, either as a primary treatment approach or in conjunction with other interventions. While physiotherapists are often regarded as specialists in this realm, other professionals like osteopaths, chiropractors, and nurses also employ manual therapy within their treatment paradigms. The efficacy of manual therapy hinges upon its engagement with a diverse array of mechanisms, including physiological, neurological, and psychophysiological aspects. Proficiency in comprehending these mechanisms is imperative for the proficient and safe application of manual therapy in clinical settings.

From the vantage point of physiotherapy, manual therapy stands as an indispensable and frequently employed modality for addressing issues related to tissues, joints, and movement dysfunction. Various established approaches to manual therapy exist, and arguably one of the most prevalent and straightforward techniques used by physiotherapists involves mobilizations inspired by the principles of the Maitland school of thought.

Key Terms

- Accessory Movement: pertains to the specialized joint actions that an individual is unable to perform independently. These movements, such as rolling, spinning, and sliding, harmonize with the physiological joint motions. During assessment, these accessory movements are evaluated passively, gauging both the range of motion and any resultant symptoms. The examination is typically conducted in the open pack position of a joint. A profound comprehension of accessory movements and their potential dysfunctions is pivotal in the effective application of the Maitland concept in a clinical setting.

- Physiological Movement: designates the motions attainable and executed actively by an individual. These movements are subject to qualitative analysis, alongside monitoring symptom responses.

- Injuring Movement: involves deliberately inducing pain or symptoms by maneuvering a joint in specific directions during a clinical evaluation.

- Overpressure: comes into play when a joint’s passive range of motion surpasses its corresponding active range. This expanded range is achieved by applying a controlled stretch at the conclusion of the normal passive movement. It’s important to acknowledge that this increased range might evoke some level of discomfort. Moreover, during the subjective assessment, considerations about potential dislocation or subluxation should be taken into account.

What is the Maitland Mobilization technique?

The Maitland concept stands as an invaluable tool for initiating assessments, offering a structured approach to formulate logical and deductive hypotheses concerning the underlying causes of movement disorders or pain. Incorporating mobilizations into the assessment process is worth considering, and a recommended resource is Maitland’s book Peripheral Manipulation, particularly the section on Initial Assessment.

Just as with any treatment determination, a proficient and impactful assessment holds paramount importance in every patient interaction. The Subjective Assessment serves as a vital component for gauging the appropriateness of mobilizations for a given patient. It also involves scrutinizing for “red flags,” such as indications of cancer, recent fractures, open wounds, active bleeding, infective arthritis, joint fusion, and other critical considerations.

Within the Objective Assessment, the multifaceted utility of mobilizations comes to the fore. Beyond their role as treatment modalities, they extend their versatility to the evaluation of a patient’s joints and tissues. This involves an analysis of extensibility, pain reproduction, identification of bony blocks, and the discernment of abnormal end feelings.

Principles of Techniques

- The Direction: Precision in determining the mobilization direction is a clinician’s responsibility, hinging on clinical reasoning and tailored to the specific diagnosis. It’s vital to acknowledge that not all directions hold equal effectiveness for any given dysfunction.

- The Desired Effect: A critical inquiry for the therapist revolves around the intended mobilization effect. Is the aim to alleviate pain or enhance flexibility through targeted stretching?

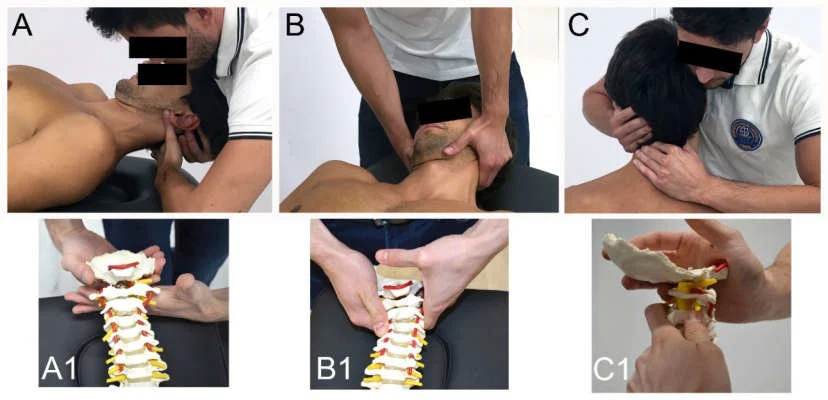

- The Starting Position: Crafting an optimal starting position for both patient and therapist lays the foundation for effective and comfortable treatment. This facet delves into the strategic positioning of the therapist’s hands to achieve a localized impact.

- The Method of Application: Comprehensive execution of the technique encompasses factors such as position, range, amplitude, rhythm, and duration, all contributing to the therapeutic process.

- The Expected Response: Anticipating the patient’s response becomes pivotal. Should they experience relief from pain, observe an increased range of motion, or encounter diminished soreness?

- How Might the Technique be Progressed: Evolving the technique involves considerations like adjusting duration, frequency, or rhythm, thus refining the treatment trajectory.

- Navigating Direction Selection: The path to suitable mobilizations involves mastering the correct type of glide, direction, and speed, underscoring their pivotal role in effective therapeutic outcomes.

Different Types of Mobilisation

Each joint boasts a distinct movement arc in comparison to other joints, thereby demanding careful consideration when selecting the manipulation direction. This is exactly where the “Concave Convex Rule” demonstrates value. However, at this juncture, let’s explore the myriad potential glides a clinician can employ:

- A-P (Anteroposterior)

- P-A (Posteroanterior)

- Longitudinal Caudad

- Longitudinal Cephalad

- Joint Distraction

- Medial Glide

- Lateral Glide

Owing to anatomical orientation and other inherent constraints, not all peripheral or spinal joints are amenable to all forms of glide. Here, we present instances of joint mobilizations across the body:

- Elbow Mobilizations

- Wrist/Hand Mobilizations

- Hip Mobilizations

- Knee Mobilizations

- Ankle and Foot Mobilizations

- Spinal Manipulation

- Shoulder Mobilizations and Manipulation

- Cervicothoracic Manipulation”

This array of techniques underlines the nuanced approaches required to effectively address diverse joint structures while ensuring optimal patient outcomes.

Concave Convex Rule

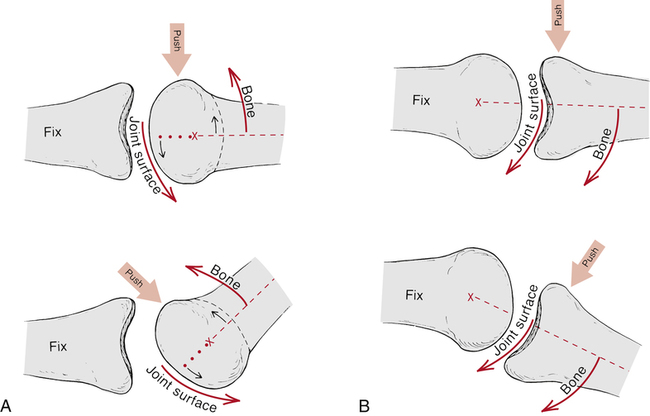

Selecting the appropriate direction for mobilization holds pivotal significance in orchestrating the desired clinical outcome. This underscores the importance of a solid grasp of Arthrokinematics. In a nutshell:

Two key principles stand out:

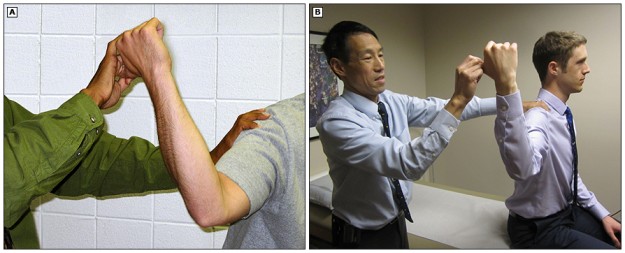

- When a convex surface, such as the humeral head, glides across a stable concave surface, like the glenoid fossa, the sliding of the convex articulation occurs counter to the motion of the bony lever (i.e., the humerus itself).

- Conversely, When a concave surface, for instance, the tibia in the talocrural joint, moves upon a stable convex surface like the talus, sliding transpires in the same direction as the bony lever.

Illustrative Scenarios:

- To enhance shoulder flexion, opt for an A-P mobilization. This aligns with the manner in which the convex humerus articulates with the concave glenoid fossa.

An even more accessible way to visualize this rule is to physically demonstrate it with your hands.

How to Choose the Grade?

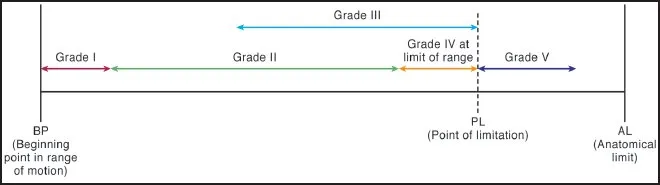

Mobilization Grading

Grade I: A slight amplitude movement executed at the initial point within the available range of motion.

Grade II: A broader amplitude movement confined within the existing range of motion.

Grade III: A significant amplitude movement extending into stiffness or muscle spasm territory.

Grade IV: A minor amplitude movement stretching into stiffness or muscle spasm.

A potential 5th grade exists, but its safe application necessitates additional training.

In various jurisdictions, securing written consent from the patient before administering grade 5 manipulation is obligatory.

The grading system splits into two categories based on clinical indications:

Lower grades (I + II) target pain reduction and irritability (measured using VAS + SIN scores).

Higher grades (III + IV) focus on elongating the joint capsule and passive supporting tissues to amplify joint stability and expand the range of motion.

Regarding the rate of mobilization, envision an oscillating motion at:

- 2Hz – equivalent to 120 movements per minute

- Lasting for 30 seconds to 1 minute.

Therapeutic Effect of Mobilization

The pain-relieving effects of mobilizations stem from the intricate interplay of multiple complex systems. As a result, a singular theory for its mechanism remains elusive. Consequently, this article aims to provide a foundational understanding, supported by evidence, while also offering supplementary links for readers seeking more comprehensive insights.

Pain Gate Theory

The Pain Gate Theory (PGT), initially proposed by Melzack and Wall in 1965, offers a commonly employed framework for understanding pain transmission. While this portrayal of pain theory is simplified and might not suit all contexts, it proves remarkably useful when conversing with patients about pain.

Grasping PGT mandates an introduction to sensory nerves. At its core, three categories of sensory nerves participate in stimuli transmission:

- α-Beta fibers: These possess large diameters and myelination, translating touch and pressure signals rapidly (50 m/s).

- α-Delta fibers: Characterized by small diameters and myelination, they relay temperature and well-localized pain (sharp/prickly) at a medium pace (15 m/s).

- C fibers: Featuring small diameters and being unmyelinated, these fibers transmit dull, persistent, and poorly localized pain at a slow speed (1 m/s).

The size of these fibers holds significance as larger nerves ensure swifter conduction, with myelin sheaths further accelerating this process. As a result, α-Beta fibers exhibit the fastest conduction, followed by α-Delta fibers, and then C fibers.

This interaction between nerves, however, is just a part of the broader narrative. Notably, only two of these nerve types serve as pain receptors: the α-Delta fibers, and α-Beta fibers are purely sensory to touch. All these nerves converge on projection cells, which journey through the spinothalamic tract of the central nervous system to the brain. In the spinal cord, inhibitory interneurons function as ‘gatekeepers.’ When no nerve sensation is present, these interneurons halt the transmission of signals up the spinal cord, effectively ‘closing’ the gate. Upon stimulation of smaller fibers, these inhibitory interneurons remain inactive, resulting in the ‘opening’ of the gate and the perception of pain. When larger α-Delta fibers are stimulated, they reach inhibitory interneurons more swiftly and, by inhibiting these interneurons, contribute to the ‘closing’ of the gate. This explains why rubbing an injured area, such as a stubbed toe, provides relief—it stimulates the α-Delta fibers, causing the gate to ‘close.’

For a different perspective, you can explore the “Pain Gate Theory Article” on Science Daily or delve into the Physiotherapy Journal Article: Pain Theory & Physiotherapy.

Descending Inhibition

The experience of pain undergoes modulation not solely during its ascent from the periphery to the cortex but also due to segmental modulation and descending regulation stemming from higher brain centers.

It’s imperative to perceive pain not as a mere linear progression, but rather as a sophisticated interplay influenced by an array of diverse biochemical and physical factors. To truly grasp this process, a comprehensive understanding of these intricacies is essential.

Should Manual Therapists Take Blood Pressure?

A contentious yet often overlooked aspect in the realm of manual therapy, particularly concerning the neck, centers around the potential impact on blood pressure. This matter was brought to light in a 2012 article authored by Taylor and Kerry, emphasizing that this issue should be a paramount concern for physiotherapists worldwide. The intricate relationship between manual therapy and blood pressure hinges on both central effects on the central nervous system (CNS) and localized effects due to the close proximity of cervical arteries. This raises a critical risk to patients, warranting explanation:

Given the anatomical immediacy of the vertebral artery to the lateral cervical presentations, the highest warning must be exercised when manipulating the cervical spine (MCS). The potential for mechanical compression or excessive stretching of arterial walls during MCS raises concerns about stroke induction, even though the precise pathogenesis of ischemia remains unknown.

Hypertension, often referred to as ‘the silent killer,’ is a prevalent issue in developed nations, attributable to poor dietary habits, elevated stress levels, and sedentary lifestyles adopted by many. Remarkably, around 30% of individuals might be oblivious to its severe consequences. Notably, hypertension stands as a primary cause of strokes, doubling as a vital indicator of stroke risk. Consequently, it should serve as a screening tool to assess the viability of subjecting a patient to cervical manual therapy. Worrisomely, in a study by Frese et al. (2002), a survey encompassing 597 physiotherapists revealed that 47% of respondents claimed to “never measure blood pressure,” with a mere 4.4% consistently checking.

The rationale most frequently cited for not monitoring blood pressure was that it’s “not pertinent to my patient population.” This stance raises concerns, given the prevalence of hypertension, obesity, and other established hypertension and stroke risk factors. Arguably, blood pressure measurement should hold significance across all patient populations.

FAQ

What is the Maitland mobilization technique?

Also understood as the Maitland concept, the Maitland concept utilizes passive & accessory mobilizations of the spine to regale mechanical aches & joint immobility. There are 5 grades of mobilization in the Maitland technique:

Grade 1 – Small action of the spine achieved within the spine opposition.

Grade 2 – Larger motions of the spine but still achieved within the spine’s opposition

Grade 3 – Large activities of the spine executed into the spine’s opposition

Grade 4 – A small motion of the spine executed into the spine antagonism

Grade 5 – An elevated-velocity motion executed into the spine opposition

What are Maitland and Mulligan’s mobilization techniques?

Mulligan mobilization permits the individuals to accomplish the offending activities in a useful pose, therefore, conducting a rewarding result. Maitland mobilization aspires to re-establish the spinning, gliding, & rolling activities of the 2 joints.

What is the Mulligan technique?

Mulligan’s approach incorporates the maintained application of manual gliding pressure to a joint, with the purpose of moving bone positional responsibilities while allowing simultaneous physiological (osteo-kinematic) movement of the joint.

What are the 4 grades of mobilization?

There are various grades of mobilization:

Gentle mobilizations (Grade I and Grade II), are utilized for pain relief while more forceful, deeper mobilizations (Grade III and Grade IV), are useful for reducing joint immobility.

What is Mulligan’s technique for a leg?

The Mulligan bent leg raise (BLR) approach is utilized for enhancing the range of straight leg raise (SLR) in subjects with LBP and guided thigh ache (Mulligan, 1999)and even in demand to enhance the flexibility of the hamstring in individuals with tight hamstring muscles.