Stress Fracture

What is a Stress Fracture?

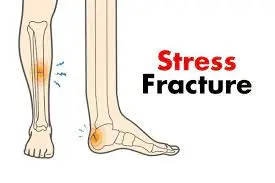

A Stress Fracture is a common orthopedic injury characterized by a small crack or hairline break in a bone. Unlike acute fractures resulting from a sudden impact or trauma, stress fractures develop gradually over time due to repetitive stress and strain on the bone.

These fractures often occur in weight-bearing bones, such as the shinbone or the bones of the feet, and are frequently associated with overuse or increased physical activity without adequate rest. While stress fractures are prevalent in athletes, they can also affect individuals with changes in activity levels, improper training techniques, or weakened bones due to conditions like osteoporosis.

Early detection and appropriate management are crucial to prevent further complications and promote optimal healing. This introduction provides a brief overview of stress fractures, setting the stage for a deeper exploration of their causes, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment.

They are common overuse injuries among athletes, resulting from repetitive submaximal loading on a bone over time. Typically observed in running and jumping athletes, they are linked to an increase in the volume or intensity of training. Predominantly found in the lower extremities, stress fractures are sport-specific, with upper extremity stress injuries, such as those in the ulna, being less frequent and also associated with overuse and fatigue.

Terminology:

Pathological fractures occur in abnormal bones, happening spontaneously or following minor trauma that would not normally cause a biomechanically normal bone to fracture; these are not stress fractures. Some authors use the term stress fracture interchangeably with fatigue fracture.

This article specifically addresses fatigue fractures, often referred to simply as stress fractures.

Pathophysiology of Stress Fracture

Maintaining healthy bones involves a delicate balance between microcrack formation and repair. The fatigue failure of bones unfolds in three stages: crack initiation, crack propagation, and eventual fracture. Typically, cracks initiate at sites of stress concentration during bone loading.

If loading persists at a frequency or intensity surpassing the rate at which new bone can be deposited and microcracks repaired, crack propagation occurs. Continuous loading may lead to the merging of multiple cracks, culminating in a clinically symptomatic stress fracture.

Without modification to loading episodes or an augmented reparative response, stress fractures can persist until structural failure or a complete fracture occurs. The X-ray image illustrates a subtle periosteal stress fracture of the tibia.

Causes of Stress Fracture

Stress fractures, such as those occurring in the metatarsal diaphysis, result from partial or complete bone fractures due to submaximal loading. Ordinarily, submaximal forces wouldn’t lead to fractures, but repetitive loading without sufficient time for healing can trigger stress fractures. The exact cause, whether contractile muscle forces or increased fatigue of supporting structures, remains uncertain, likely involving contributions from both factors.

Up to 20% of injuries in sports medicine clinics may be related to stress injuries, with weight-bearing limbs more susceptible. Tibia, metatarsals, and fibula are frequently affected, and medial tibial stress syndrome (shin splints) is a common early manifestation. Stress injury locations vary by sport, with the ulna most affected in the upper extremity. Women experience stress fractures more than men, often in preseason and predominantly in the foot and lower leg.

- Track athletes commonly experience fractures in the navicular, tibia, and metatarsals.

- Distance runners frequently report stress fractures in the tibia and fibula.

- Dancers often suffer from stress fractures in the metatarsals.

- Military recruits commonly fracture the calcaneus and metatarsals.

Intrinsic factors contributing to stress fractures include:

- Low bone density

- female gender

- History of stress fracture

- Hormonal factors: late menarche (>15 years), oligo or amenorrhoea

- BMI < 19

- Low energy availability and/or eating disorders

Systemic medical conditions affecting metabolic and nutritional status, such as thyroid dysfunction.

Risk Factor of Stress Fracture

Athletes engaged in high-impact sports on their lower bodies face an elevated risk of stress fractures, including:

long-distance running and track and field sports.

- Basketball.

- Tennis.

gymnastics (with gymnasts also prone to hand and wrist stress fractures). - Dance.

Several health conditions can heighten the risk of stress fractures, including:

- Osteoporosis (sometimes referred to as insufficiency fractures)

- Bunions.

- High-arched feet.

- Flat feet.

- Vitamin D deficiency.

- Overweight or obese.

- Eating disorders.

Symptoms of a Stress Fracture

While symptoms can vary, a prevalent complaint is pain during activity that is alleviated with rest. Key indicators include:

- Gradually worsening pain during the aggravating activity over time.

- Swelling and tenderness in the area of pain may also be present.

Differential Diagnosis of Stress Fracture

When patients exhibit tenderness or oedema following a recent surge in activity or repetitive motion with limited rest, stress fractures should be considered. The differential diagnosis, influenced by the location, often encompasses:

- Tendinopathy

- Compartment syndrome

- Nerve or artery entrapment syndrome

- Shin splints

Diagnosis of Stress Fracture

While bone scans have long been considered the gold standard for assessing stress-induced injuries, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has gained prominence, though bone scans remain widely used in many scenarios.

Radiography reveals that two-thirds of initial radiographs may appear normal early in the course of a stress fracture, with half ultimately proving positive as healing progresses (specific but not sensitive). Even during the healing phase, radiographic findings can be subtle and easily overlooked.

MRI proves effective in diagnosing stress fractures, especially when patients display strong clinical symptoms despite normal initial radiographs. CT is valuable for well-delineated bone imaging, particularly in challenging diagnoses like tarsal navicular stress fractures and linear stress fractures in the tibia.

Examination:

Patients typically report an insidious onset of pain without specific trauma, often associated with a significant volume of a specific exercise, such as running, increased training intensity or volume, or a change in training surface. Initially, symptoms worsen during training but may progress to pain during daily activities, improving with activity cessation.

On examination:

- Focal tenderness in the suspected stress injury area.

- Possible soft tissue swelling, with soft tissue tenderness suggesting muscle injury or an early stress reaction, while bony tenderness leans towards stress fracture.

- Some stress injury areas, like the pelvis and sacrum, may be clinically subtle, requiring a higher index of suspicion based on history alone.

The ‘one leg hop test’ helps distinguish between medial tibial stress syndrome and tibial stress fractures. Patients with stress injuries tolerate repeated jumping, while those with stress fractures experience pain during hops, typically upon landing.

Physiotherapy Management for Stress Fractures

Individualized management is crucial for effective care. In most instances, initial management involves a tailored rest period to facilitate stress fracture healing. This may entail the use of crutches or a weight-bearing boot in moderate-to-severe cases to alleviate bone stress.

Early-stage treatment comprises analgesia, modified weight-bearing, and activity adjustments, including discontinuation of the triggering activities. If walking induces pain, temporary immobilization may be necessary. Activity modification suggestions encompass water fitness, cycling, and elliptical exercises to maintain strength and fitness. Following a pain-free rest period, a gradual return to activity is advised, accompanied by ongoing physical therapy.

Rehabilitation and strengthening, coupled with a phased return to activity, play a crucial role in preventing or minimising the risk of re-injury. Developing a tailored programme is essential to safely and effectively reintegrating clients into their activities or sports.

Continuous monitoring of symptoms is vital, ensuring the patient remains pain-free during the progression back to activity. Pain should not worsen during or after exercise.

Should symptoms reappear, activity modification (load, volume, and/or intensity reduction or use of non-impact modes) and further investigation for alternative causes may be necessary.

Education and risk factor optimization are pivotal for prevention, including:

- Appropriate footwear for specific exercises

- Gradual progression when starting a new exercise programme

- Warm up before running.

- Combined stretching and muscle strengthening

- Proper cool-down after exercise.

Management of Stress Fractures by Region

Different types of stress fractures require tailored approaches:

- Leg and Foot Stress Fractures:

- Femoral Shaft: Most can be conservatively managed with rest, activity modification, and protected weight-bearing. If there’s low bone mineral density, age exceeds 60, or there’s fracture completion or displacement, ORIF with an intramedullary nail may be indicated.

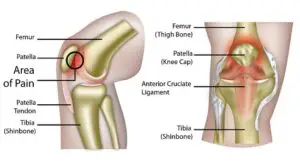

- Patella: managed conservatively with immobilization and a gradual return to activity.

- Tibia: Most shaft stress injuries can be conservatively managed, with considerations for surgery if specific criteria are met. Medial tibial plateau stress fractures and medial malleolus stress fractures are generally treated conservatively but may require orthopaedic consultation.

- Fibula: Conservative management with rest, immobilization, activity modification, and a gradual return to play.

- Tarsals: Calcaneal stress injuries respond well to conservative measures. Navicular stress injuries, high-risk for nonunion, may need non-weight-bearing and close follow-up or, if a fracture is completed, ORIF with screw fixation. Medial cuneiform and some talus stress injuries can also be conservatively managed.

- Metatarsal Fractures: Tailored approaches based on the specific nature of the injury

- Non-Lower Limb Stress Fractures:

- Rib: common in rowers and typically managed conservatively.

Pars Interarticularis of the Lumbar Spine: Treatment depends on the severity and may involve a combination of rest, bracing, and a gradual return to activity. - Pelvis: managed conservatively with rest, crutches if needed, and a gradual return to sport.

- Rib: common in rowers and typically managed conservatively.

Each case requires careful consideration of factors like age, bone density, and fracture characteristics to determine the most effective management strategy.

Prevention of Stress Fracture

Mitigating bone stress injuries involves addressing modifiable risk factors through a comprehensive, whole-body approach. Consider the following recommendations to reduce the risk of bone stress injuries:

- Enhance Strength and Flexibility: Strengthen muscles and improve joint flexibility to enhance their ability to absorb force, reducing the impact on bones.

- Use Proper Equipment: Ensure you have the right gear for training, including well-maintained shoes. Take time to break in new equipment to minimize the risk of stress injuries.

- Incorporate cross-training: Diversify exercises to reduce repetitive running and jumping. Include lower-impact activities like biking, rowing, and swimming alongside running-based sports.

- Prioritise Recovery: Allow adequate recovery time after activities, aiming for at least 7 hours of sleep each night and one full rest day per week. Take 1- to 2-week breaks between sports seasons.

- Gradual Progression: Ease into new sports seasons or training programmes with a gradual increase in walking, running, and jumping activities. Avoid sudden transitions from inactivity to daily activity.

- Choose Softer Surfaces: Train on softer surfaces like a treadmill, track, or trail to reduce impact on bones.

- Proper Nutrition: Ensure you consume enough calories to support your exercise level. Adequate energy is essential for bone building during recovery and healing.

- Optimise Vitamin D Intake: Maintain optimal vitamin D levels to enhance calcium absorption and support overall bone health.

Conclusion

Stress injuries often stem from overtraining without sufficient recovery time.

The majority of stress injuries can be effectively addressed through a combination of rest, analgesia, activity modification, cross-training, and a gradual reintegration into sports.

Non-operative management proves successful for many low-risk stress injuries, allowing a phased return to play.

However, high-risk stress injuries may necessitate surgical intervention, particularly when conservative approaches prove ineffective.

FAQ

What are the 4 signs of a stress fracture?

The following are the most typical signs of a stress fracture:

Discomfort that worsens and begins while exercising.

Discomfort that remains after ceasing activities.

Pain that is more apparent when you’re at rest.

Tenderness on or around the afflicted bone, even to a mild touch.

Swelling.

Can a stress fracture heal on its own?

Particularly if you detect it early. Usually, all that’s needed is to cut back on weight-bearing activities (sports included, as well as how much you stand and walk), and make sure your body is getting enough of the minerals and nutrients that your bones require.

Can you walk on a stress fracture?

Tiny cracks called stress fractures might appear in the weight-bearing bones. These are sometimes brought on by repetitive stress to the bone, which can happen via long marches, frequent jumping up and downs, or long runs.

How do you fix a stress fracture?

Instead, try low-impact activities like cycling or swimming. Severe stress fractures that don’t heal on their own may require surgery. Usually, the doctor will use one or more of these fasteners pins, screws, plates, or a mix of them to fuse the tiny bones in your foot and ankle.

Is a stress fracture serious?

In contrast to a blown-out knee or a shattered arm, stress fractures may not look like a serious sports injury. Nonetheless, if you suspect you may have a stress fracture, you should see a doctor. Stress fractures should be taken carefully. Stress fractures can cause major consequences if they are not treated.

What are the 3 causes of stress fractures?

Stress fractures can result from practicing or training too frequently without getting enough rest. Taking up a new sport or physical activity without the necessary instruction, gear, or training.Increasing your level of exercise (workouts, training, or other physical activity) quickly.

How long do stress fractures last?

The majority of stress fractures take six to eight weeks to fully heal. Your rehabilitation treatment plan may consist of the following, depending on the type and severity of your injury: Apply the RICE (rest, ice, compression, and elevation) technique to your afflicted limb to alleviate pain and inflammation. medicine that reduces inflammation.

What age is stress fractures most common?

Competitive athletes in their teens or early adult years are most commonly affected by stress fractures. Stress fractures are an overuse ailment that can affect athletes of any gender, but they tend to affect women and girls more frequently than males.

Do stress fractures hurt all day?

Normally felt across the wounded area, the pain normally takes a few weeks to develop. Usually, it becomes better while you rest and gets worse when you put weight on the wounded area. As it worsens, the discomfort may become more persistent at night and while you’re sleeping.

Should you exercise with a stress fracture?

Stress fractures should not be interfered with while they are mending. Exercises that involve high impact and weight bearing should be avoided until your doctor gives the all-clear. When your foot discomfort has lessened to a dull ache, you could feel that going for a run is ok.

Do stress fractures show up on X-rays?

CT scans. Regular X-rays performed soon after the onset of symptoms typically fail to show stress fractures. Stress fractures may not be visible on X-rays for several weeks, or even longer than a month. A bone scan.

Reference

- Professional, Cleveland Clinic Medical. “Stress Fractures.” Cleveland Clinic, my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/15841-stress-fractures. Accessed 12 Nov. 2023.

- Stress Fractures – OrthoInfo – AAOS. orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/diseases–conditions/stress-fractures. Accessed 12 Nov. 2023.

- “Stress Fractures.” Physiopedia, www.physio-pedia.com/Stress_Fractures. Accessed 12 Nov. 2023.

8 Comments