GREATER TROCHANTERIC PAIN SYNDROME (GTPS)

Description

Hip pain is a common orthopedic problem. Greater trochanteric pain syndrome (GTPS), previously known as trochanteric bursitis, affects 1.8 per 1000 patients annually.

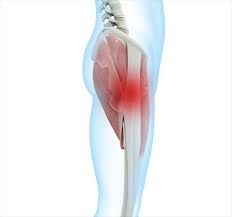

Results from degenerative changes affecting the gluteal tendons and bursa.

Patients complain of pain over the lateral aspect of the thigh that is exacerbated with prolonged sitting, climbing stairs, high impact physical activity, or lying over the affected area.

A range of causes, including the gluteal tendinopathy, trochanteric bursitis, and external coxa saltans.

The pathogenesis is not completely understood – symptoms are associated with myofascial pain rather than inflammation.

The main bursae that associated with this GPTS are the gluteus minimus, subgluteus medius, and the subgluteus maximus.

The hip joint withstands loads up to 6 to 8 times body weight during normal walking or jogging. Due to constant mechanical load, this joint is prone to wear and tear injury during athletic maneuvers.

Proposed clinical definition of GTPS:

“A history of lateral hip pain and no difficulty with manipulating shoes and socks together with clinical findings of pain reproduction on palpation of the greater trochanter and lateral pain reproduction with the FABER test.

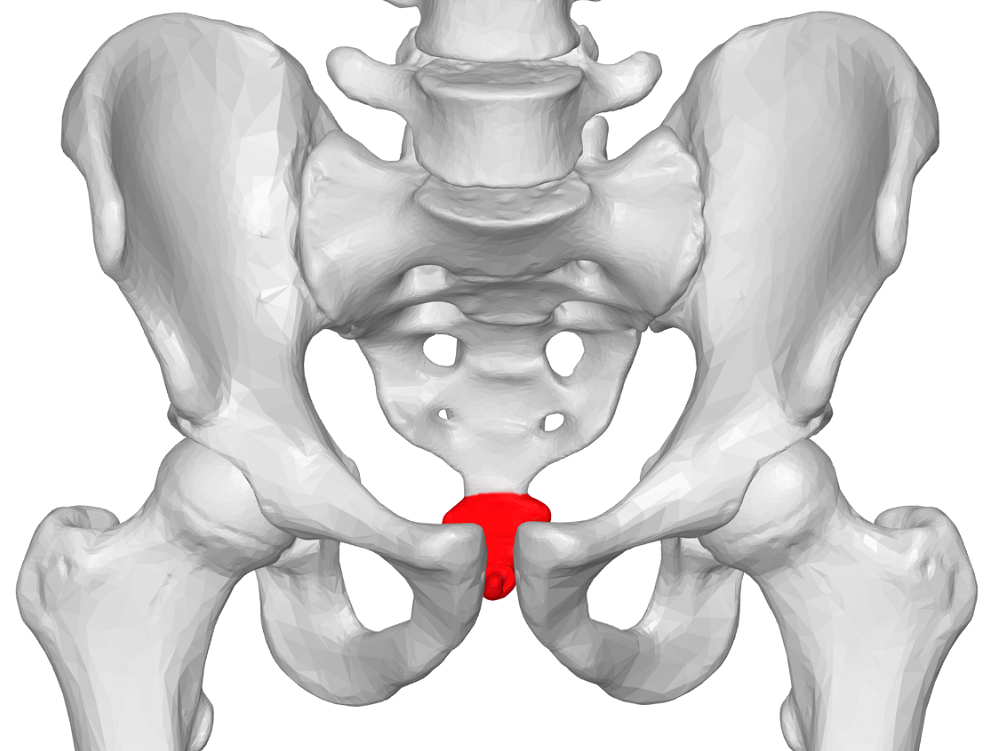

Anatomy related to Greater trochanteric pain syndrome

The greater trochanter is situated on the proximolateral side of the femur, just distal to the hip joint and the neck of the femur.

The tendons of the Gluteus Medius, Gluteus Minimus, gluteus maximus (GMax) and the tensor fascia lata (TFL) attach onto this bony outgrowth (apophysis). The greater trochanter is seen to have 4 facets, the above-mentioned muscle attachments have been equated to the “rotator cuff of the hip”

External iliac fossa is the origin of the Gluteus Medius and Gluteus Minimus muscles (Gluteus Medius attaching to the lateral and superolateral facets and the Gluteus Minimus inserting onto the anterior facet).

The TFL lies over the GMed and GMin tendons and inserts onto the ITB

Number of bursa on average of 6 bursae.

The locations of these bursae vary greatly – the size, location and number are not consistent.

Four bursae are consistently present (multiple secondary bursa).

The three chief bursae at the hip include the subgluteus maximus, the subgluteus minimus and the subgluteus medius bursa.

These bursae and the periosteum of the greater trochanter are innervated by a small branch of the femoral nerve.

Hip joint stability : Gluteus Maximus muscle tensions the ITB via its ITB attachment and assists with improving the hip joint’s passive stability.

ITB is also tensioned by the vastus lateralis, TFL and limits hip internal rotation and adduction passivley.

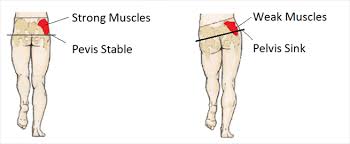

Gluteus Medius prevents excessive hip adduction and is often seen as the primary stabilizer of the pelvis.

Hip joint innervation: rami articulares of the obturator nerve, the femoral nerve, sciatic nerve,a branch of the femoral nerve that supplies the periosteum and bursa of the greater trochanter.

Epidemiology

- Lateral hip pain affects 1.8 out of 1000 patients annually.

- Greater trochanteric pain syndrome is most prevalent between the fourth and sixth decades of life.

- Studies have shown that GTPS has a strong correlation with female gender and obesity.

Aetiology of Greater trochanteric pain syndrome

Multi-factorial with both intrinsic and extrinsic components. The literature review states the following main causative factors.

- Repetitive activity

- Mechanical overload

- Altered cellular response/failed healing

- Training errors: high-intensity training, high mileage, running on an asymmetrical surface, cambered road

- Sedentary lifestyle

- Increased adiposity

- Scoliosis

- Leg length discrepancy

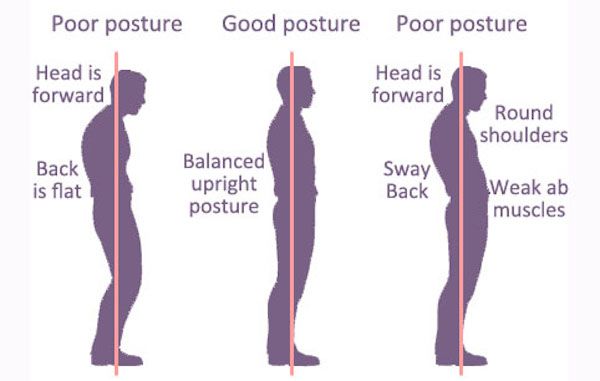

In people with weak hip abductors, particularly Gluteus Medius, greater hip adduction is seen causing increased compression of the Gluteus Medius and Gluteus Mininus tendons at the greater trochanter. With the increased adduction, the ITB exerts higher compressive forces on the gluteal tendons, amplifying the compression

Hip positions in higher ranges of flexion may also increase the compression of the Gluteus Medius and Gluteus Minimus tendons due to increased tension in the ITB, explaining why pain that occurs with prolonged sitting.

Pelvic control in a single leg stance position – controlled 70% by the abductor muscles, ITB tensioners (Gluteus Max, TFL and vastus lateralis) account for the remaining 30%. People with gluteal tendinopathy tend to have Gluteus Medius and Gluteus Minimus atrophy and TFL hypertrophy. Weakness and/or muscle bulk changes impact the balance of the abductor mechanism and increase the compression of the gluteal tendons.

Women are more prone to GTPS because of pelvic biomechanics, different activity levels in the population and hormonal effects. Females have a smaller insertion of the Gluteus Medius tendon, resulting in: smaller area across which tensile load could be dissipated; moment arm shorter, causing reduced mechanical effeciency.

Increased fluid within the bursa is thought to be a consequence of the tendinopathy rather than it being due to inflammation of the bursa.

Tears of the Gluteus Medius and Gluteus Minimus tendons are a frequently missed cause of GTPS.

Up to 25% of middle-aged women can have Gluteus Medius tears. It is also found in up to 10% of middle-aged men.

Tears can be acute but degenerative tears are far more common. It was thought that the Gluteus Medius tendon was most frequently affected but Gluteus Minimus tendons tears were more frequent than Gluteus Medius tears

Gluteus Medius and Gluteus Minimus tears were associated with tendon and enthesis degeneration.

Tears at the Gluteus Medius tendon insertion can be complete, intrasubstance or partial, with partial tears occurring most frequently. Complete tears of the Gluteus Medius are associated with a coinciding Gluteus Minimus tear but MRI and ultrasound investigations very rarely identify the Gluteus Minimus tear.

Most tears are found at the insertion of the anterior and middle portions of the Gluteus Medius and Gluteus Minimus tendons. Coxa saltans or Snapping Hip Syndrome presents in about 5% to 10% of the general population.

Causes:

Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome can be caused by direct trauma from a fall onto your side, prolonged pressure to the hip area, repetitive movements (walking/running), commencing unaccustomed vigorous exercise, weight-bearing on the one leg for long periods, hip instability or the result of a sporting injury.

Symptoms:

Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome causes pain over the greater trochanter that may extend into the lateral thigh/leg. We characterise GTPS by the ‘jump’ sign where palpation of the greater trochanter causes the person to nearly jump off the bed.

- Pain is usually episodic and will worsen over time with continued aggravation.

- Tender lateral hip when palpated, especially near the greater trochanter

- Pain is worse when lying on the affected side, especially at night.

- Pain following weight-bearing activities – Standing, walking, running, climbing stairs.

- Pain may refer to the lateral thigh and knee

- Pain with prolonged sitting

- Sitting with crossed legs increases pain

- Pain can also occur when lying on the non-painful side if the painful hip falls into adduction

- Pain is usually episodic and will worsen over time with continued aggravation

- There may be hip muscle weakness.

Diagnostic Procedures

There is no one specific test to confirm GTPS and the tests available lack validity when done in isolation.

Diagnostic accuracy can however be improved when a combination of tests is used

- The single leg stance test for 30 seconds has a positive predictive value (PPV) of 100% and also has a very high sensitivity when pain is produced within 30 seconds of standing on the painful side.

- Resisted hip medial rotation, lateral rotation and abduction can also be used to asses for GTPS. Resisted lateral rotation has the highest sensitivity (88%) and specificity (97.3%) when compared to resisted medial rotation and abduction. The highest specificity is achieved when the test is done in 90° hip flexion.

- FADER, OBER and FABER – aim to increase the tensile load on the gluteal tendons

- The ability to put one’s socks and shoes on without help will also help differentiate GTPS from OA, where the GTPS patient has no difficulty during the acitivity.

- The “jump sign” carries a PPV of 83% so direct palpation of the greater trochanter is helpful in diagnosing GTPS.

- The Trendelenburg sign is present in patients with GTPS and when used to assess for a Gluteus Medius tear, it has a sensitivity of 73% and a specificity of 77%.

- If external coxa saltans is suspected – FABER, Ober test, Hula-Hoop test and active hip flexion followed by passive extension and abduction.

Imaging is only suggested in the following situations:

- When it comes to diagnosing gluteal tears. Ultrasound or MRI should be used to confirm the diagnosis if suspected clinically. Ultrasound is the most accurate when assessing a tendon where MRI is helpful for differential diagnosis.

- When conservative treatment has failed.

- When diagnosis is unclear.

Treatment:

Treatment targets pain management, improving hip strength and control and a progressive return to sport.

Physiotherapy Management

PHASE I – Pain Relief & Protection

- You are managing your pain. Pain is the main reason that you seek treatment for GTPS. In truth, it was the final symptom that you developed and should be the first symptom to improve.

- Managing your pain is best achieved through ice therapy, relative rest and techniques or exercises that unload the injured structures.

- Eliminating the compressive load is vital to the recovery of GTPS. Avoid positions that lengthen the affected hip including crossing your legs, ‘popping’ your hip out in standing, lying on either side, walking on cambered surfaces and in the initial stages stretching the muscles on the outside of the hip bone.

- Physiotherapist will use an array of treatment tools to reduce your pain and inflammation. These include ice, electrotherapy, acupuncture, unloading taping techniques, soft tissue massage and temporary use of a mobility aid (e.g. cane or crutch) to off-load the affected side.

- If the pain does not resolve some cases may respond to a local corticosteroid injection.

PHASE II – Restoring Normal ROM, Strength

- As your pain and inflammation settle, physiotherapist will turn their attention to restoring your normal hip joint range of motion, muscle length and resting muscle tension. Muscle strengthening and endurance, proprioception, balance and gait (walking pattern) retraining will follow.

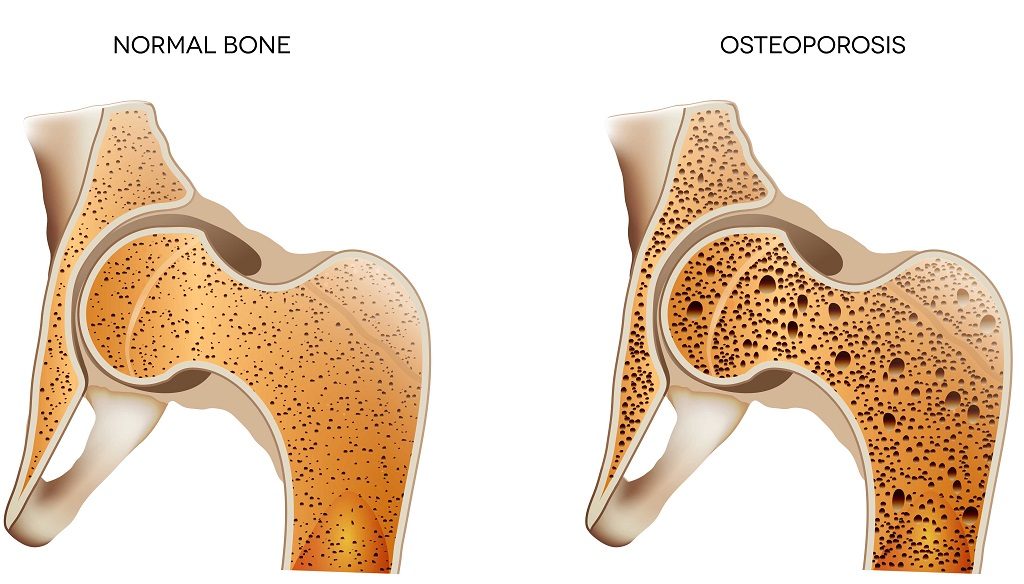

- Treat comorbidities- osteoarthritis, labral tears can frequently coexist.

PHASE III – Restoring Full Function

The final stage of your rehabilitation aims at returning you to your desired activities. Everyone has different demands for their hips that will determine what specific treatment goals you need to achieve. For some people, it may be only to walk around the block. Others may wish to run a marathon. Physiotherapist will tailor your hip rehabilitation to help you achieve your own functional goals.

How to Return to Sport after Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome

- As soon as you are cleared by your physiotherapist you can return to your activity – but take it easy for a while.

- Don’t start at the same level as before your injury. Build back to your previous level slowly, and stop if it hurts.

- Warm-up before you exercise.

- After the activity, apply ice to prevent pain and swelling.

- Continue your hip stabilisation exercises to prevent a recurrence.

Exercises for early stages Stand:

- holding on to a stable surface, such as a chair or table, for balance. Lift your painful leg out to the side and then slowly lower back to normal standing position. Aim to complete three sets of 10-12 repetitions.

- Stand with your painful leg away from the wall. Lift your unaffected leg up to 90 degrees. Push against the wall with your knee. You should feel the muscles around the edge of your outside hip working. Hold this position for 20-30 seconds. Repeat three times

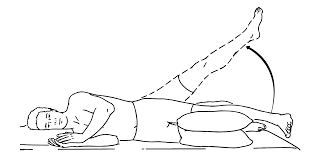

- Lie on your unaffected side with a pillow between your knees, as shown in the photo. Make sure your top leg is in line with your body. Lift the leg up towards the ceiling and slowly lower back to the starting position. Complete three sets of 10-12 repetitions.

Exercises for later stages:

- Lie with your painful leg towards the floor, with your knees bent behind you.. Push up on your elbow, lifting your hips up so they are in line with your body. Hold for 20-30 seconds. Repeat three times. To make this exercise more challenging you can complete with your knees straight.

- With a resistance band around your ankles, stand in a mini squat position. Take 10 slow and controlled steps to the left and then repeat to the right. Ensure you stay in a squat position. Repeat three times.

- Without using the handrail, step up and then slowly down from the bottom step of the stairs with your painful leg. Complete three sets of 10-12 repetitions.

2 Comments