Elbow Joint: Anatomy, Function

The elbow joint is a synovial joint found in the upper limb between the arm and the forearm. It is the point of articulation of three bones:

The humerus of the arm and the radius and the ulna of the forearm.

The elbow joint is classified structurally as a synovial joint. It is also classified structurally as a compound joint, as there are two articulations in the joint. Synovial joints, also called diarthroses, are free movable joints. The articular surfaces of the bones at these joints are separated from each other by a layer of hyaline cartilage. Smooth movement at these joints is provided by a highly viscous synovial fluid, which acts as a lubricant.

A fibrous capsule encloses the joint and is lined internally by a synovial membrane. Synovial joints can be further categorized based on function. The elbow joint is functionally a hinge joint, allowing movement in only one plane (uniaxial).

The elbow is the visible joint between the upper and lower parts of the arm. It includes prominent landmarks such as the olecranon, the elbow pit, the lateral and medial epicondyles, and the elbow joint. The elbow joint is the synovial hinge joint between the humerus in the upper arm and the radius and ulna in the forearm which allows the forearm and hand to be moved towards and away from the body.

The Complex Anatomy of the Elbow

The elbow joint is where the distal humerus meets the proximal radius and ulna bones. It is known as a trochleogingylomoid joint as it can flex and extend as a hinge (ginglymoid) joint as well as pivot around an axis (trochoid motion) known as pronation and supination. It is an extremely congruent and stable joint. Due to its complexity, even after severe injury, it is more prone to stiffness than instability.

Structures of the Elbow Joint

Articulating Surfaces

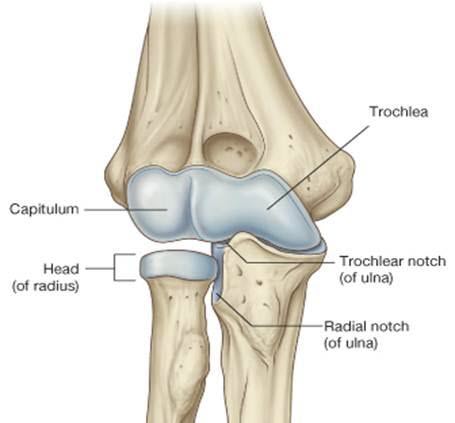

It consists of two separate articulations:

- Trochlear notch of the ulna and the trochlea of the humerus

- Head of the radius and the capitulum of the humerus

Note: The proximal radioulnar joint is found within the same joint capsule of the elbow, but most resources consider it as a separate articulation.

- Type of joint: Hinge joint

- Bones: Humerus, radius, ulna

- Mnemonics : CRAzy TULips (Capitulum = RAdius, Trochlear = ULnar)

- CUTER (Capitulum: Ulnar, Trochlea: Radial)

- Ligaments near the elbow: Ulnar collateral ligament, radial collateral ligament, annular ligament, quadrate ligament

- Blood supply: Proximal to elbow joint – Ulnar collateral artery, radial collateral artery, middle collateral artery

- Distal to elbow joint – Radial recurrent artery, ulnar recurrent artery

- Movements: Flexion – Biceps brachii, Brachialis, Brachioradialis muscles

- Extension – Triceps brachii muscle

- Common conditions: Fractures, epicondylitis, arthritis, venipunctures

Osteology

There are three bones that comprise the elbow joint:

- the humerus

- the radius

- the ulna.

These bones give rise to three joints:

- Humeroulnar joint: Humeroulnar joint is the joint between the trochlea on the medial aspect of the distal end of the humerus and the trochlear notch on the proximal ulna. The ulnohumeral hinge joint is responsible for flexion and extension. The spool-shaped trochlea of the humerus articulates with the greater sigmoid arch of the proximal ulna.

- Humeroradial joint: Radiocapitellar Joint is the joint between the capitulum on the lateral aspect of the distal end of the humerus with the head of the radius. The radiocapitellar joint is where the radius and humerus articulate. It is partly responsible for pronation and supination. The capitellum of the lateral distal humerus is a spherical structure onto which the concave surface of the proximal radial head articulates.

- Proximal Radioulnar Joint: The proximal radioulnar joint is a trochoid joint responsible for the pronation or supination of the forearm. The peripheral edge of the radial head articulates with the radial notch of the ulna.

The humeroulnar and the humeroradial joints are the joints that give the elbow its characteristic hinge-like properties. The rounded surfaces of the trochlea and capitulum of the humerus rotate against the concave surfaces of the trochlear notch of the ulna and head of the radius.

This joint, however, is considered to be a separate articulation from those forming the elbow joint itself. The proximal radioulnar joint is the articulation between the circumferential head of the radius and a fibro-osseous ring formed by the radial groove of the ulna and the annular ligament that holds the head of the radius in this groove. The proximal radioulnar joint is functionally a pivot joint, allowing a rotational movement of the radius on the ulna.

Carrying Angle

The carrying angle is measured when the elbow is in full extension and supination. It is an angle measured along the long axis of the humerus and ulna. In men, it is approximately 11-14° and in women 13-16°. Is it appropriately named as it allows our arms to clear our hips as we walk and allows objects to be carried.

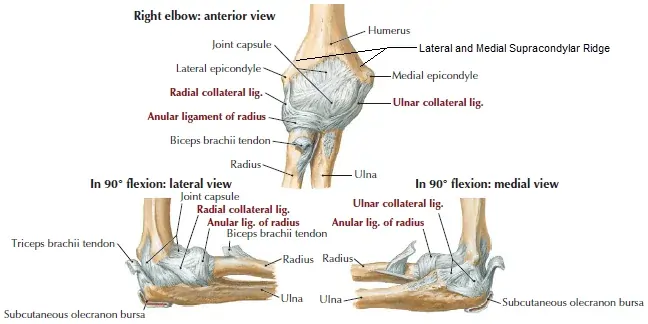

Ligaments of the elbow joint

There are a collection of ligaments that connect the bones forming the elbow joint to each other, contributing to the stability of the joint. The humeroulnar and the humeroradial joints each have a ligament connecting the two bones involved in the articulation:

the ulnar collateral and the radial collateral ligaments.

The ulnar collateral ligament extends from the medial epicondyle of the humerus to the coronoid process of the ulna. It is triangular in shape and is composed of three parts: an anterior, a posterior, and an inferior band.

The radial collateral ligament has a low attachment to the lateral epicondyle of the humerus. The distal fibres blend with the annular ligament that encloses the head of the radius, as well as with the fibres of the supinator and the extensor carpi radialis brevis muscles.

The annular ligament also reinforces the joint by holding the radius and ulna together at their proximal articulation. The quadrate ligament is also present at this joint and maintains constant tension during pronation and supination movements of the forearm.

Musculature

There are 4 main muscle groups at the elbow. The anterior bicep group, the posterior tricep group, the lateral extensor-supinator group, and the medial flexor-pronator group

Each muscle group applies a compressive load to the elbow joint when they contract.

- Primary Elbow Flexors

- Brachialis

- Biceps brachii

- Brachioradialis

- Secondary Elbow Flexors

- Pronator teres

- Extensor carpi radialis longus

- Flexor carpi radialis (at elbow angles 50 degrees or more)

- Primary Elbow Extensors

- Triceps

- Anconeus

- Secondary extensors

- Flexor Carpi ulnaris

- Extensor carpi ulnaris

- Pronation

- Pronator teres

- Pronator quadratus

- Supination

- Mainly Biceps

- Assistance from supinator

- Lesser degree finger and wrist extensors

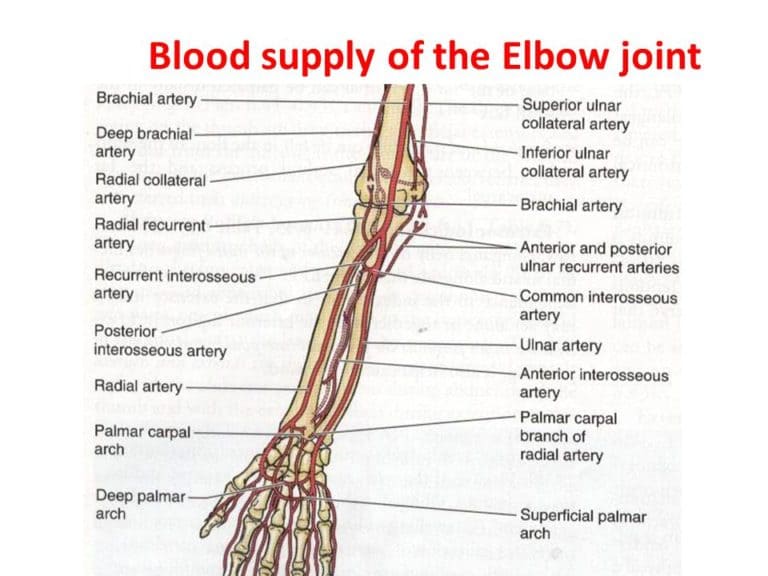

Blood supply and innervation

The blood supply to the elbow joint is derived from a number of periarticular anastamoses that are formed by the collateral and recurrent branches of the brachial, profunda brachii, radial and ulnar arteries.

Proximal to the elbow joint, the brachial artery, the largest in the arm, gives off two branches, a superior and inferior ulnar collateral artery. The profunda brachii gives off a radial collateral and a middle collateral artery. These pass towards the joint contributing to the anastomotic loop supplying the joint.

Distal to the elbow joint, the radial artery gives off the radial recurrent artery, and the ulnar artery gives off the anterior and posterior ulnar recurrent arteries. These arteries ascend towards the elbow joint, anastamosing with the branches from the brachial and profunda brachii arteries in the arm.

Movements of Elbow Joint

As the elbow joint is a hinge joint, movement is in only one plane. The movements at the elbow joint involve movement of the forearm at the elbow joint. Flexion of the forearm at the elbow joint involves decreasing the angle between the forearm and the arm at the elbow joint. Extension involves increasing the angle between the arm and forearm. These movements are performed by two groups of muscles in the arm: the anterior compartment and the posterior compartment of the arm.

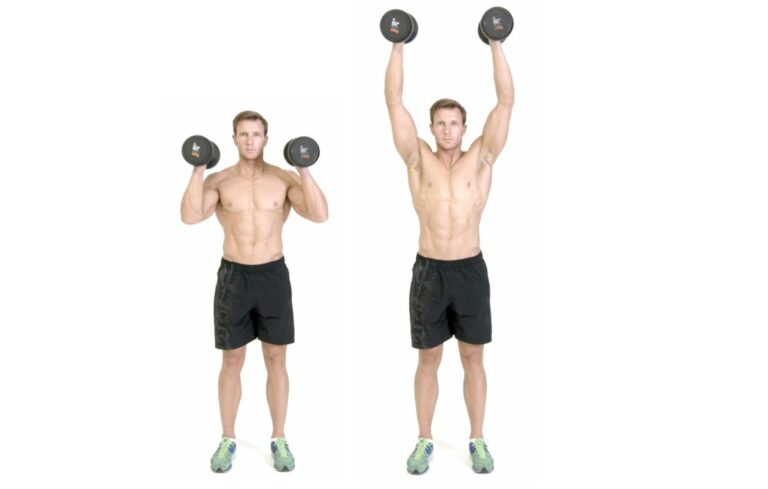

Elbow joint Flexion

Most of the muscles producing flexion are found in the anterior compartment of the arm. There are two muscles in this compartment that produce flexion at the elbow joint:

Biceps Brachii Muscle originates as two heads. The tendon of the long head originates from the supraglenoid tubercle of the scapula. It passes through the joint capsule of the shoulder joint and through the bicipital groove on the anterior surface of the humerus. The short head of the biceps brachii muscle originates from the coracoid process of the scapula. These heads join together to form the biceps brachii muscle belly.

The muscle inserts via a single tendon onto the radial tuberosity distal to the elbow joint. In the forearm, there is a continuation of this tendon as a flattened connective tissue sheath, the bicipital aponeurosis. This aponeurosis blends with the deep fascia in the anterior forearm.

Brachialis originates from the distal half of the anterior surface of the humerus, as well as from the intermuscular septa on either side of the anterior compartment. It is located deep in the biceps brachii muscle. It forms a singular tendon that inserts onto the tuberosity of the ulna.

Both the Biceps brachii and brachialis muscles are innervated by the Musculocutaneous nerve.

While the biceps brachii and the brachialis muscles are the main flexors of the elbow joint, the brachioradialis muscle is also involved in the flexion of the forearm at this joint. Brachioradialis originates from the lateral aspect of the distal humerus above the lateral epicondyle. It inserts onto the lateral aspect of the distal radius. Although this muscle is primarily in the forearm, it crosses the elbow joint so therefore it acts on the elbow joint. It is innervated by the radial nerve.

Mnemonic

Learning the muscles that bend the elbow becomes child’s play if you anchor them to a mnemonic like the one below.

3 B’s bend the elbow

- Biceps

- Brachialis

- Brachioradialis

Extension of Elbow Joint

Extension of the forearm at the elbow joint is the increase of the angle at the elbow to bring the forearm back to the anatomical position from a flexed position. There is one muscle involved in extension, the triceps brachii muscle. It is the only muscle in the posterior compartment of the arm.

Triceps Brachii originates as three heads. The long head originates from the infraglenoid tubercle of the scapula, the lateral head originates from the lateral aspect of the humerus above the radial groove, and the medial head originates from the medial aspect of the humerus below the level of the radial groove. The three heads converge on a single tendon that inserts onto the olecranon of the ulna. It is supplied by the radial nerve, which passes down through the arm in the radial groove between the lateral and medial heads of the muscle.

While flexion and extension are the only movements that can occur at the elbow joint itself, movement is also afforded at the proximal radioulnar joint, which contributes to the elbow joint. Movements at this joint are called pronation and supination. These are rotational movements that occur when the distal end of the radius moves over the distal end of the ulna by rotating the radius in the pivot joint formed by the circular head of the radius, the radial groove of the ulna, and the annular ligament.

Pronation of forearm (Pronatio antebrachii);

Pronation of forearm (Pronatio antebrachii)

Pronation and supination are easily visualized when the elbow is flexed at 90°. Supination is where the palm of the hand is facing upwards; pronation is the rotation of the forearm so that the palm is facing downwards. In the anatomical position, the forearm is in the supine position. Pronation in the anatomical position is the movement of the forearm so that the palm is facing posteriorly.

Pronation and Supination

The radiocapitellar joint and proximal radioulnar joint are responsible for pronation and supination. Normal ROM is considered approximately 180° (80°-90° pronation and 90° supination). 100° of movement (50° pronation and 50° supination) is considered adequate for most ADLs. If pronation ROM is lost this can be compensated by using shoulder abduction. But, there is no compensatory action for supination and as such a loss of supination ROM can pose a greater disability than a loss of pronation ROM.

Common Activity Limitations and Participation Restrictions (FunctionalLimitations/Disabilities)

- Difficulty turning a doorknob or key in the ignition

- Difficulty or pain with pushing and pulling activities, such as opening and closing doors

- Restricted hand-to-mouth activities for eating and drinking and hand-to-head activities for personal grooming and using a telephone

- Difficulty or pain when pushing up from a chair

- Inability to carry objects with a straight arm

- Limited reach

Elbow Joint Clinical Examination

Elbow Examination

Special Tests

- Cozen’s Test

- Elbow Flexion Test

- Elbow Quadrant Tests

- Elbow Valgus Stress

- Moving Valgus Stress Test

- Elbow Varus Stress

- Golfer’s Elbow Test

- Mill’s Test

- Polk’s Test

- Pronator Teres Syndrome Test

- Tinel’s Sign at Elbow

- Wartenbergs Sign

Conditions

- Cubital Tunnel Syndrome

- Ligamentous Injuries

- Lateral Epicondylitis

- Medial Epicondylitis

- Olecranon Bursitis

- Olecranon Fracture

- Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Elbow

- Radial Head Fracture

- Ulnar Nerve Entrapment

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

Procedures

Elbow Arthrolysis

Elbow Arthroscopy

Open debridement or synovectomy

Radial head excision and synovectomy

Radial head replacement

Reconstruction elbow replacement

Release of lateral epicondylitis

Total elbow replacement

Ulnar nerve decompression

Differential Diagnosis of Elbow Pain

Lateral elbow pain is the most common site for pain to be felt at the elbow. Lateral epicondylalgia or tennis elbow is a common cause of lateral elbow pain but it is not the only cause. There are many conditions that can cause pain and dysfunction at the elbow and a systematic differential diagnosis is important to identify all contributing and predisposing factors.

Lateral Elbow Conditions

Lateral Epicondylalgia

Osteochondral Fractures of the capitellum

Osteochondritis Dissecans

Synovial Plica

LCL tear/ strain

Fractures of the Radial Head

Loose Bodies

OA radiohumeral joint

Synovitis RH joint

Radial tunnel syndrome

Posterior interosseous Nerve entrapment

Medial Elbow Conditions

Medial Epicondylalgia

MCL strain/rupture

Ulnar Nerve Entrapments

Medial olecranon fossa impingement

Posterior Elbow Conditions

Avulsion fractures of the olecranon

Olecranon spurs

Olecranon posterior impingement

Triceps tendinopathy/ rupture

Olecranon Bursitis

Postero/lateral dislocation

Anterior Elbow Conditions

Biceps insertion tendinopathy rupture

Brachialis Strain/ Tear

Degenerative joint changes

Adult annular ligament

Factors Contributing to Elbow Pain

Elbow pain does not occur in isolation. Many structures can refer pain to the elbow and others can contribute to the development of elbow pain and dysfunction. It has been shown in various studies that structures distant from the elbow contribute to the development of elbow pain and dysfunction. These can be from a variety of dysfunctions namely neural, myofascial, joint-related, or even centrally mediated.

Physiotherapy Assessment of the Elbow

Subjective Examination

As with all conditions, a detailed subjective examination is your foundation for being able to clinically reason. Specific questioning around the history of the condition, aggravating and easing factors as well as 24-hour patterns will help to form a picture of what is going on. Asking about any other problems anywhere else in the body may help give an indication of contributing factors. General health and red flag screening are important to exclude any serious pathologies as well as indicate if any co-morbidities may be contributing to the condition.

Imaging

X-rays are normally performed in elbow trauma and are important in excluding fractures and dislocations. Ultrasounds and MRIs are normally performed when there is suspected soft tissue (eg tendon) involvement. Imaging for the elbow may be useful for visualizing pathophysiology but the severity of pathophysiology seen on imaging does not correlate with the level of symptoms. Positive findings on imaging should be interpreted with caution and should not be used as a primary clinical assessment tool. Negative findings on imaging may be helpful to rule out pathology.

Objective Examination

A comprehensive physical examination is performed to confirm or negate your potential hypothesis formed after the subjective examination.

Local examination of the elbow

- Active and passive movements

- Muscle strength testing

- Ligament stress tests

- Any other appropriate special tests

- Grip strength measured with a grip dynamometer

- Palpation and manual examination of the joints and soft tissue structures

- Thermal hyperalgesia

Examination of other structures as identified on subjective examination which may cause elbow pain

- Cervical Spine

- Thoracic Spine

- Shoulder

- Wrist

- Neurological System and Neurodynamics

- Any other potential contributing system

Physiotherapy Management of Elbow Pain and Dysfunction

It is well-accepted that a comprehensive management programme of elbow pain and dysfunction requires a multi-modal approach. Active management of musculoskeletal pain disorders involving self-management is more supported by evidence than passive management strategies. Treatment should be aimed not only at the local elbow structures found on assessment but at all the contributing factors identified during the examination.

Pharmacotherapy

NSAIDs- possibly more useful in reactive tendinopathy than degenerative tendinopathy

Corticosteroid medication- the evidence shows short-term relief but outcomes are worse at 6-12 months compared to wait-and-see or physiotherapy management. Corticosteroid injections may not be appropriate as a first-line intervention for lateral elbow tendinopathy

Centrally Acting Analgesics- may be appropriate for patients with central sensitization

Prolotherapy and Nitric Oxide patches- possibly more beneficial in patients with more chronic LET of more than 3 months

Manual Therapy

There is moderate evidence that manual therapy can have immediate beneficial effects on pain and grip strength. Mulligan mobilisations which are aimed at pain-free movement during a mobilization technique have been shown to be beneficial. Manual therapy at the cervical and thoracic regions have also shown to provide clinical benefits in LET management.

Education

As in any condition education around the pathophysiology of the condition and symptom modification, stages of healing, and general self-management are important.

31 Comments